T. Carlos Anderson's Blog

October 2, 2025

“You Should Write a Memoir”

“You Should Write a Memoir”

Jim Harrington stared back at me over lunch with a scowl. He had just told me to fudge off, in so many words. His mouth, however, betrayed a slight smile. He knew I was right as I met his uneven scowl with a wide, confident grin. I had just told him that he needed to write a memoir.

It was October 2022. La Fruta Feliz, an unpretentious Mexican restaurant on Austin’s eastside, has been Jim’s go-to lunch spot for years. We had met there a number of times for almuerzo since 2017, shortly after we were introduced to one another by mutual friend and pastoral colleague, Jay Alanis. Jim, after a decades-long career as a civil rights lawyer, became an Episcopal priest and served a Spanish-speaking immigrant congregation, Proyecto Santiago, at St. James Episcopal Church. When we met—included as an addendum story below—Jim invited me to preach as part of his troop of once-a-month Spanish preachers for Project Santiago. All of us, including Jay, did so pro-bono style, following Jim’s lead as an unsalaried priest.

I knew of Jim and of some of his work before I met him. As I got to know him better, he shared with me his “call story”—how he originally intended to become a Catholic priest, back in the late sixties, but switched gears and eventually went to law school instead. All of this happened in his home state of Michigan, where he had worked alongside seasonal farmworkers—all of them Mexican or of Mexican descent—for seven consecutive summers. The work involved setting up health clinics, enforcing minimum wage laws, distributing supplemental food and vouchers, and conducting evening adult education and worker rights classes. As it turned out, there would be time for seminary and ordination later. Decades later. Fresh out of law school in the early seventies, Jim came to South Texas to continue to work alongside farmworkers. And just like in Michigan, working alongside farmworkers in Texas branded him as an “outside agitator” in the eyes of owner-planters. It was exactly where Jim felt called to be, doing exactly what he felt called to do: confronting injustices in the spirit of God-inspired anger and compassion—and pissing off entrenched power brokers in the process.

What a story in and of itself, and what a story for a memoir.

After Jim quit scowling at me over the chips and salsa on our table at La Fruta Feliz, I told him I had a contact at UT Press, which I figured to be a most appropriate publisher for such a book. Jim taught as an adjunct professor in UT’s law school for twenty-six years while heading up the Texas Civil Rights Project in Austin. Jim busted his tail in the writing process, and UT Press took him up on his proposal. The Texas Civil Rights Project: How We Built a Social Justice Movement was released on September 16. Jim has been invited to speak at the Texas Book Festival, November 8–9, to be held in downtown Austin, in and around the Capitol.

At La Fruta Feliz once again with Jim, August 2025

At La Fruta Feliz once again with Jim, August 2025For all of my needling and mischief, Jim inscribed a pre-release copy of his book for me. Having read a number of early manuscript chapters at Jim’s request, I relished the opportunity to read the hardcover book, the final product of Jim’s faithful rewriting and tweaking with the help of an experienced editor. I am profoundly biased, obviously, but this book is a powerhouse and a whirlwind simultaneously. Jim’s focus never wavers from the folks—Texas Valley farmworkers and others—whom he and the TCRP represented over the years. There’s also a pointed focus, humorous at times, upon the politicians, owner-planters, bad-actor law enforcement officers and establishment sycophants they encountered along the way.

A heads up: Don’t think that this history/memoir doesn’t have anything to say about what’s happening in our country and society today. I purposely use a double-negative to make my point! As many of us see the current administration’s policies eroding basic civil rights, including voting rights, this book shows how the (metaphoric) battles were won for worker and civil rights and can been won today. It’s an encouragement to read how truth can be spoken to power effectively, and how the strength of a united people group can withstand and even defeat the negative effects of long-standing racism and worker abuses.

Jim shares his call story, concluding with his law school graduation ceremony when he pinned a United Farm Workers “Boycott Grapes” button to his commencement cap, in the first chapter—and an incredible ride ensues from there as he comes to the Texas Valley in 1973. Subsequent topics include organizing (protesting, marching, striking and negotiating) alongside and on behalf of farmworkers, confronting police brutality, fighting for grand jury reform, and taking on the Texas Supreme Court to institute legal pro-bono support for low-income Texans. Jim’s writing puts the reader in the midst of the action described in the book: in the fields alongside farmworkers, in TCRP offices as legal strategies are formed, in the courtrooms where judges and juries contemplate giving TCRP clients their constitutional rights and privileges.

You already know I’m biased when it comes to this book. It fits the bill for many of us—citizens concerned that the United States is losing its place as the lead guardian of democracy, lawyers and law students, and those wanting to forge ahead in the important work of standing up for what’s right in the face of ongoing injustice.

For the record, I’m not the only one who suggested to Jim that he write his memoir. My words, as if the last straw, were simply delivered at the right time. And harking back to that lunch in October 2022, if you know Jim, you know exactly what he did say to me when I told him that he needed to write a memoir. He didn’t say “fudge.” Ha.

There are plans for the book to be translated into Spanish. Jim should have los detalles of the Spanish version’s availability around the beginning of 2026.

Addendum Story: My wife, Denise, has worked as a stalwart paralegal at Bickerstaff, Heath, Delgado and Acosta since 2008. The firm employed Texas civil rights legend Myra McDaniel, a UT law school grad and the first African American to serve as Texas Secretary of State, (1984–87). Upon completion of her term, she became a managing partner at Bickerstaff. Denise and all other employees at the firm were honored to work alongside Ms. McDaniel, who was universally loved and admired.

Myra was a member of St. James Episcopal Church on Austin’s eastside. She passed away at 78 years of age in 2010. Her funeral at St. James, which has a large rounded sanctuary, was standing room only with more than 400 mourners. I attended the funeral service with Denise.

Years later, in 2017, after I had resigned my pastor position at St. John’s/San Juan Lutheran, Denise suggested that we go to worship “at Myra’s church.” I knew the priest at St. James, Madeline Shelton Hawley, and we greeted her before worship started. I mentioned to Madeline that we came to worship at St. James that morning because Denise had worked with Myra McDaniel. Madeline smiled, and simply said that everyone at the congregation loved Myra and missed her greatly.

Toward the end of worship, Pastor Madeline asked all the visitors to stand to be recognized. Of ten or so visitors that Sunday, Denise and I were the last to be recognized as the pastor went around the sanctuary. Because Pastor Madeline knew me, I was pretty sure that I was about to receive the standard positive call-out from one clergy to another—“What an honor to have Pastor Tim Anderson with us here today.” Blah, blah, blah.

To my surprise, that didn’t happen. Pastor Madeline gave the honor of visitor name recognition to “Denise Anderson, who used to work with Myra McDaniel!” At the mention of Myra’s name, the entire congregation—some 150 souls—turned around with wonder and surprise on their faces and began to clap. Denise beamed. And then Madeline simply closed the introduction and said, “and Denise is here today with her husband.”

It was great! It was the first time ever Denise got props in a church setting over and above her pastor husband! It was more than overdue; it was just, right, and salutary!

When the service had concluded and Denise and I were visiting with folks in the narthex, I happened to see my friend and former congregant from St. John’s/San Juan Lutheran, Jay Alanis, a seminary professor at Lutheran Seminary Program of the Southwest. He was surprised to see me and said, “Pastor, there’s someone I want to introduce you to!” Jay was preparing to preach at Proyecto Santiago—he was one of Jim’s troop of Spanish preachers—and brought me over to Jim. Jay introduced us and told Jim that I would be a good candidate for Spanish preaching at Proyecto Santiago.

With Padre Jim at Proyecto Santiago in 2024

With Padre Jim at Proyecto Santiago in 2024The rest is history, as they say—at least, for me!

T. Carlos “Tim” Anderson – I’m a Protestant minister and Director of Austin City Lutherans (ACL), an organization of partners in Austin, Texas working together to serve low-income individuals and families.

Check out any of my books – Just a Little Bit More (2014), There is a Balm in Huntsville (2019), and There is a Balm in Wichita Falls (2024).

September 26, 2025

“America, América” and Fascism – Book Review

In America, América, Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Greg Grandin continually reminds readers that WW II was a battle against European fascism—Hitler in Germany and Mussolini in Italy. Even though Spain maintained a veiled neutrality during the war, Franco was a fascist leader. The Empire of Japan, part of the Axis alignment, isn’t typically defined as fascist, but it had fascist characteristics.

As three generations have passed since the end of the war in 1945, most of us have no working definition of fascism. We’re familiar with democracies, communism and dictatorships. What is fascism? Grandin’s book, as it details in its middle sections the post-WW II political landscape in the Americas, describes fascism as “a virulent, mobilized nationalism” exhibiting the following characteristics:

* government led by charismatic leader

* extreme nationalism exhibited by leader and supporters

* a defined enemy (or enemies)

* the use of military force upon a country’s own citizens

* the curtailing of free speech, specifically restricting the freedom of the press

* the political obliteration of checks and balances, specifically shaping the judicial court system to represent the will of the leader and ruling party

* the co-opting of religion for state purposes

In our post-Cold War era, fascism has reemerged in the Americas. Grandin writes, “In any given election, agitated conservatives might tap into misogyny, gender panic, Christian supremacy, or racism to win, sometimes spectacularly so, such as when Jair Bolsonaro took power in Brazil in 2018, or in 2023, when Hayekian Javier Milei won in Argentina. El Salvador’s president, Nayib Bukele, has, in the name of fighting gang violence, done away with due process to line up thousands of young men, stripping them naked and displaying them to the world with shaved heads. Octavio Paz died before he could witness such a Dantesque display of fascist dehumanization, or otherwise he might have revised his assertation that Latin America’s Catholic culture produced no pariahs” (pgs. 624–25).

This book went into press as Donald Trump assumed his second presidency. Not quite a year into this presidency, it’s become obvious that Trump is following a fascist playbook.

Out of a total 625 million inhabitants, Grandin writes, 480 million Latin Americans currently live under some type of social-democratic government. The best hope to confront and overcome the neofascist movement, he says, is for these governments to continue to pursue policies that champion a humanist and social welfare bent. Chile’s example, Grandin writes, is the starkest: Allende’s social democracy (1970–73) followed by Pinochet’s authoritarianism (1973–1990). Chile has steadfastly, in the subsequent decades, rejected the latter’s Hayekian-influenced economic shock therapy of deregulation, privatization and austerity measures. All this—along with political repression—just so Chile can have a burgeoning multi-millionaire class? A majority of Chileans, for decades, have said “no.”

In Brazil, Jair Bolsonaro was recently sentenced to 27 years in prison for attempting to undermine the democratic presidential election of 2022, which he lost. In many ways, his and his supporters’ actions mirrored those of Donald Trump and his supporters during the January 6, 2021 insurrection at the US Capitol. Bolsonaro has appealed his sentence. The largest Latin American county with a population of 213 million, Brazil’s current democracy was established in 1988 after more than twenty years of military dictatorship. In June 2023, Brazil’s Superior Electoral Court banned Bolsonaro from running for president (or any political office) until 2030 for his part in undermining the 2022 election.

It begs the question: Will the majority of the US’s 341 million citizens reject Trump’s continuing foray into fascism?

T. Carlos “Tim” Anderson – I’m a Protestant minister and Director of Austin City Lutherans (ACL), an organization of partners in Austin, Texas working together to serve low-income individuals and families.

Check out any of my books – Just a Little Bit More (2014), There is a Balm in Huntsville (2019), and There is a Balm in Wichita Falls (2024).

Check out any of my books – Just a Little Bit More (2014), There is a Balm in Huntsville (2019), and There is a Balm in Wichita Falls (2024).

September 4, 2025

“America, América” – Book Review

In October of 1982, I climbed dirt roads on the outskirts of Cusco, Perú with a college classmate. Cusco, in a bowled valley 11,152 feet above sea level in the beating heart of the Andes Mountain range, shrank behind us as we ascended. In front of us, unending stacks of mountain tops beckoned. The whole experience—the expanse and sheer beauty of the Andes, the history of the ancient Incan capital, the freedom to hike where few of our contemporaries even imagined—was exhilarating. The two of us vowed to return some day to Perú.

Augustana College (Rock Island, Illinois) had what was called a “foreign quarter study” program. With some forty other classmates and four professors, we spent ten weeks in Mexico, Colombia and Perú. Our history teacher on the trip, Dr. Tom Brown, mesmerized us with lectures on the Black and White Legends of the Spanish Conquest. Toward the end of the trip, a handful of us talked about spinning Neil Young’s “Cortez the Killer” as the first thing we’d do upon returning home. He came dancing across the water, with his galleons and guns . . .

Cusco environs

Cusco environs 1982

1982Participating in the program changed my life. I did go back to Perú, as a seminary student, and learned Spanish de verdad. Subsequently, I’ve spent three plus decades working as a pastor in Texas, using English, of course, y el bendito Español. Often times I’ve described myself as “a missionary to white people.” That description isn’t necessarily pejorative. Another way to describe the work I’ve done and continue to do: I’m a “bridger.”

Yale history professor Greg Grandin’s new book, America, América, tells a broader story of American history—of English-speaking, Spanish-speaking and Portuguese-speaking America. In Grandin’s telling of the American story, there is no dichotomy of US and Latin American histories as North, Central and South American histories bridge together.

I sense that Grandin would consider himself a “bridger” as well. His ability to merge Latin American events within the larger framework of “American history” works. His occasional use of Spanish in the text is well-placed and adds appropriate spice and effect.

The shared evil of slavery is the initial touchpoint of his telling.

Whereas the United States needed the brutal Civil War to resolve its adherence to slavery, the majority of Latin American nations—Cuba and Brazil are the outliers, not abolishing slavery, respectively, until 1886 and 1888—wrote abolitionism into their founding constitutions in the early nineteenth century. Independence from Spain logically translated into freedom for all inhabitants—whether brown, black or white; male or female; native- or foreign-born.

The Spanish priest Bartolomé de Las Casas (1484–1566) exposed the wickedness and inhumanity of Spanish colonial slavery. Early on in the Conquest, Las Casas himself was an encomienda owner with slaves. His eventual, steady conversion to abolitionism, primarily documented in his A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies (written in 1542 and published in 1552), established a tradition that abolitionists built upon for close to 300 years, cresting with the leadership of the “Great Liberator,” Simón Bolívar.

Liberty for all was an American concept established—on constitutional paper, at least—by a dozen newly established Latin American countries by 1825, while at the same time the number of slaves in the United States grew to more than 2 million. It would be another 40 years until slavery was officially abolished in the US.

On December 1, 1936, President Franklin Roosevelt arrived in Buenos Aires, Argentina to give the keynote address at the Inter-American Conference for the Maintenance of Peace. Grandin recounts how FDR championed his “good neighbor policy” as a guard against the possibility of European fascism—ascendant in Germany and Italy, and rising in Spain—establishing itself in the Americas. Additionally, the “good neighbor policy” was Roosevelt’s promise of no armed US intervention into the twenty-one Latin American countries represented at the conference. Roosevelt’s formula—social welfare, freedom of thought, free commerce, and mutual defense—echoing some of his New Deal constructs, offered, he said, “hope for peace and a more abundant life” for Latin Americans and the whole world.

In this pre-WW II era, German and Italian nationals lived in established communities in Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay, Chile and Perú. The threat of fascist advance in South America was real.

Two Roosevelt administrators, Henry Wallace and Sumner Welles, worked the “good neighbor policy” in Latin America. Wallace, the Secretary of Agriculture (and Roosevelt’s vice-president from 1941–44), was convinced that raising the world’s standard of living was the surest way to promote democracy in the midst of fascist advances. He promoted labor clauses favoring worker rights—fair wages, health care, and a ban on prisoner labor—in government procurement contracts. Welles, a bilingual State Department envoy who specialized in Latin American affairs, was of the opinion that a peaceful and secure world was only possible if the gap between “the haves” and “the have nots” was narrowed.

Their naysayers were legion and vociferous. By the time Roosevelt died (in office) in 1945, Wallace’s and Welles’s influence had waned. Even so, their viewpoints stand out as high-water marks of New Deal thinking. Poverty and inequality breed discontent and unrest, much more so in the modern world than in times previous.

As the Cold War and the thwarting of communism took on absolute precedence in US foreign policy, the good neighbor policy toward Latin America disappeared like a mouse scurrying into hole. The era of US support of proxy wars in Central and South American countries commenced—first in Guatemala, later in Nicaragua and El Salvador. The US would later carry out covert operations in Honduras, Panama and Haiti.

Grandin details how the International Court of Justice—the legal arm of the United Nations—ruled in 1986 that the US was guilty of waging an illegal war in Nicaragua and imposed a $17 billion reparations judgment on the US. The court ruled that Washington’s patronage of the Contras was illegal as was the mining Nicaragua’s harbors and distributing “how-to” torture manuals to anti-Sandinistas. In response, the Reagan administration simply announced it was withdrawing from the court’s jurisdiction. Grandin calls it a watershed moment of unilateralism and the blunting of international law.

Shortly thereafter, with the fall of the Soviet Union and the absence of anything akin to FDR’s good neighbor policy, US and Latin American relations took on, according to Grandin, the status of “informal dependency.” The economic policies of neoliberalism, or globalization—as it has done in the US—has redistributed wealth upward in Latin American countries as its populaces have suffered through economic austerity measures, lower wages, hollowed-out social services and weakened labor protections. Inequality is on the rise in Latin America. As wealth siphons upward, so does political power.

The authoritarian right—Trump in the US, Bolsonaro in Brazil, Milei in Argentina, Bukele in El Salvador—and the accompanying reemergence of fascism will be the topic of my next blog on Grandin’s America, América.

This is the first of two blog posts on the new book, America, América (Penguin Press, 2025) by Yale historian Greg Gandin.T. Carlos “Tim” Anderson – I’m a Protestant minister and Director of Austin City Lutherans (ACL), an organization of partners in Austin, Texas working together to serve low-income individuals and families.

Check out any of my books – Just a Little Bit More (2014), There is a Balm in Huntsville (2019), and There is a Balm in Wichita Falls (2024).

Check out any of my books – Just a Little Bit More (2014), There is a Balm in Huntsville (2019), and There is a Balm in Wichita Falls (2024).

July 30, 2025

Remembering Linda White

When doing research that resulted in the 2019 publication of There is a Balm in Huntsville, I was told by three people—Andrew Papke, David Doerfler, and Ellen Halbert—that I needed to meet and talk to a woman named Linda White. Each of them told me that Linda was an incredible person, a crime-victim survivor whose story was unparalleled. I consequently travelled to Magnolia, Texas in April of 2017 and spent the better part of a day interviewing Linda. My three encouragers were exactly right. Linda’s story was harrowing—the horrific murder of her daughter Cathy at the hands of strangers—and astounding—her life-long response to this tragedy positively influenced countless others.

Linda passed away on July 3, 2025. She was 84 years old. When I met her in 2017, she carted around an oxygen tank and told me that because of COPD, she only had a few more years to live. A lung transplant might have worked for Linda, but she told me that its possibility held no sway for her. The many accomplishments of her life—recorded on my phone that day—had already crafted a beautiful and lasting legacy. By that point in time, Linda had spoken to and with hundreds of people about her story of recovery and restoration. The list included TV personalities Oprah and Montel Williams and their wide audiences; it also included hundreds of prisoners who heard her story through a prison ministry program (Bridges To Life) designed to help them recover and turn their lives around. Yes, that’s the kind of person she was. Incredible. An outlier. One of the best of human beings.

Early on in her grieving and recovery process, Linda figured out that the healing she deeply craved wasn’t going to come via vengeance. The two young murderers of her daughter were sentenced to be in prison for a long time—more than 50 years—but she needed something beyond the state’s lawful retribution to reclaim, if even possible, her life.

In her search, she discovered something called “restorative justice.” Its emphasis on “repairing the damage done by crime” gave her life renewed purpose. Her reparation process was a lengthy one, but it was thorough. There is a Balm in Wichita Falls (published in 2024) fully details Linda’s recovery. As she told me, her recovery process and subsequent advocacy work for restorative justice practices were the best ways for her to honor her daughter’s life.

The dedication of the first of the two Balm books reads as follows: “This book is dedicated to Dr. Linda White—crime victim, restorative justice advocate, college professor to prisoners, and Victim-Offender Dialog mediator.” Parts of her story were included in the original manuscript for that book, but were eventually edited out. Little did I know at the time, however, that the outtakes of that book would turn out to be the basis for the second book.

For the second book, Linda’s recovery story intertwines with that of her good friend Ellen Halbert. Linda and Ellen didn’t know each other at the time of their simultaneous victimizations, but their journeys later merge. They form a deep friendship and work together for understanding, healing, and justice—There is a Balm in Wichita Falls tells their amazing stories in narrative, page-turning fashion.

In the last number of years, in society and politics, we’ve heard increased usage of “us versus them” verbiage and witnessed a renewed emphasis on retribution. Public safety, of course, is a crucial societal pillar produced by just laws and a fair and effective judicial system. Demonizing others and using fear as a political lever, however, contribute to the erosion of public safety. Linda’s and Ellen’s voices offer a better way forward, in the spirit of Jesus who said to “love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you.”

Similarly, the New Testament book of James states that “human anger does not produce the righteousness of God.” Thanks to Linda White, who looked beyond the limited scope of retribution to discover healing and experience restoration. This is her lasting legacy—the promotion of a different road forward for healing.

T. Carlos “Tim” Anderson – I’m a Protestant minister and Director of Austin City Lutherans (ACL), an organization of partners in Austin, Texas working together to serve low-income individuals and families.

Check out any of my books – Just a Little Bit More (2014), There is a Balm in Huntsville (2019), and There is a Balm in Wichita Falls (2024).

Check out any of my books – Just a Little Bit More (2014), There is a Balm in Huntsville (2019), and There is a Balm in Wichita Falls (2024).

March 25, 2025

Bluebonnets and Redistribution

I’ve been smitten by bluebonnets ever since moving to Texas more than 30 years ago. I carefully seeded a side garden area at our home in Houston—etching the pebble-like seeds with a knife as instructed by the package—but to no avail. It wasn’t until we moved to Austin that I had any luck. One spring I bought a dozen bluebonnet plants from a local nursery and nurtured them into our front and back yards. They bloomed gloriously. About a month later, their pods twisted out seeds upon the ground, and the cycle of bluebonnet death and resurrection took hold in our yard. Ever since, for some 25 years, we’ve had a bounty of beautiful blue blooms every spring.

Most people know me as “Pastor Tim” as I’ve worked as a pastor in Austin for a few decades, currently as the director of Austin City Lutherans. We call our organization “the other ACL,” and we serve low-income neighbors with a food pantry, a high-quality childcare center, and a move-in ministry providing furniture and household items for people exiting or at-risk of homelessness.

I have another identity, however. As some of my neighbors know, I am the “South Austin Bluebonnet Seed Robin Hood.” Each spring I spy public places that have an abundance of bluebonnets, and when they seed out in May and June, I redistribute a portion of their seeds to other locales that need a splash of spring color.

In recent years, I’ve especially focused on the Davis Lane median near our house in South Austin. For years, Davis Lane was a dead end. In 2016 it became a through-way, spruced up with a tree-lined and rock-covered median.

I started my Robin Hood actions on the median five years ago, faithfully dispersing fresh seeds upon its rocky cover. Not all Texans know, but brave little bluebonnet sprouts come up with the fall rains in October and November. Not all the little plants that sprout make it to blooming glory in March and April. It’s a tough go for the little plants as the adversity of cold and occasional snow and ice come in the winter months. When it freezes, the plants’ circular clusters of leaves (called basal rosettes) literally lay down, spreading close to the ground. But they persevere as they patiently await the warming spring sun which coaxes them to stand tall. Sun rays spill forth from the sky, and bluebonnet flower cones race upward and explode into a bounty of azure and cobalt. Have you ever experienced a spring in Texas when there were no bluebonnets? I haven’t—every year the bluebonnets faithfully do their thing. They sprout, survive, persevere, and then thrive.

I’ve seen growth and progress each year of my Davis Lane project as the plants’ coverage has spread. This spring’s blooms have been decent (the continuing drought is a mitigating factor) with five or six large pockets of bluebonnets up and down the median. The plants have naturally done their work, but I’ve continued to do the work of redistribution, sharing seeds from places abundant to this place of need.

Similarly, the work of redistribution by Austin City Lutherans’ volunteers blesses those in need. Our Bread For All Food Pantry helps feed more than 600 households (about 2,500 people) each month as we share food donated by supporters and the Central Texas Food Bank. Mariposa Family Learning Center provides high-quality childcare to a dozen families—through its tuition-subsidy model—who would otherwise have no access to such programming. And in the past three years, Austin City Lutherans’ Move-In Ministry crews have brought furniture and household items to more than 200 families and individuals. We serve people who come from varying situations: men and women living on the streets for years; women fleeing, with children, situations of domestic violence; refugees legally in the country, always with children, seeking asylum and a new start free from oppression and tyranny; and, young adults aging out of the foster care system.

The Move-In Ministry wouldn’t be able to assist these folks without our donors who have generously given their furniture and household items for redistribution: tables and chairs, living room sets, dressers, end tables and lamps, pots, pans, dishes and silverware. These basic items help give recipients a feeling of stability—“home”—in their new places.

When people have what they need—food, shelter, security—they have better opportunity to pursue purposeful living. ACL works together, in the spirit of biblical justice, toward this end utilizing the power of redistribution. This power works for flowers toward the end of beauty and wonder, and it works for people toward the end of dignity and grace.

T. Carlos “Tim” Anderson – I’m a Protestant minister and Director of Austin City Lutherans (ACL), an organization of partners in Austin, Texas working together to serve low-income individuals and families.

Check out any of my books – Just a Little Bit More (2014), There is a Balm in Huntsville (2019), and There is a Balm in Wichita Falls (2024).

Check out any of my books – Just a Little Bit More (2014), There is a Balm in Huntsville (2019), and There is a Balm in Wichita Falls (2024).

January 22, 2025

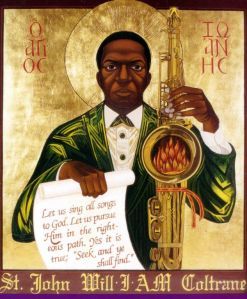

John Coltrane – A Love Supreme

John Coltrane released his masterpiece A Love Supreme in February 1965. For those of you unfamiliar with Coltrane’s work, A Love Supreme is as fresh and timeless today as it was sixty years ago. Accessibly melodic, Coltrane’s exuberant tenor sax fuses with McCoy Tyner’s teeming piano chords and riffs to produce an unparalleled thirty-three-minute session of ascendant and flowing grace.

Give it a look and listen here:

Coltrane’s road to A Love Supreme was anything but straightforward. He was born in North Carolina in 1926. His father passed away when he was only twelve years old. Around this same time, a church music director introduced the young adolescent Coltrane to the saxophone. After moving to Philadelphia when he was seventeen, Coltrane enlisted in the US Navy and played clarinet in a military band while serving in Hawaii. He returned to Philadelphia in 1946 and dedicated himself to becoming a jazz musician.

He found success and played alongside the biggest names of the early bebop era: Thelonious Monk, Dizzy Gillespie, Johnny Hodges, and Miles Davis.

The hungry ghost of addiction haunted him; he was booted out of Miles Davis’s band in 1957 for continued heroin use, including a near overdose. The close call, however, propelled him to clean up. From the autobiographical liner notes of A Love Supreme: “During the year 1957, I experienced, by the grace of God, a spiritual awakening which was to lead me to a richer, fuller, more productive life.” His calling was “to make others happy through music,” which, he claimed, was granted to him through God’s grace. “No matter what . . . it is with God. He is gracious and merciful. His way is in love, through which we all are. It is truly – A Love Supreme – .”

Yes, Coltrane’s credo – like some of his music later in his career – is a bit vague and esoteric. Let me put the credo in other terms, more accessible: love is a sufficiency all its own. In Just a Little Bit More: The Culture of Excess and the Fate of the Common Good, I detail the societal desire and drive that is never satisfied with enough, always seeking “just a little bit more.” Love is the antidote to the pursuit of more and more; it helps us to be grateful, to relax, to rest, to enjoy, to share, and to know what and when is enough. Love also helps us to do great things – busting our tails in the process – for our neighbor and the common good. Love covers it all.

John Coltrane died of liver cancer in 1967, having completed only 40 years of life on this earth. Forgive the obvious cliché – his music does live on. Coltrane biographer Lewis Porter (John Coltrane: His Life and Music, University of Michigan Press, 2000) explains that Coltrane plays the “Love Supreme” riff (four notes) exhaustively in all possible twelve keys toward the end of Part 1 – Acknowledgement, the first cut on the disc. Love as sufficiency – it covers all we need and then some.

The conclusion of Coltrane’s liner notes: “May we never forget that in the sunshine of our lives, through the storm and after the rain – it is all with God – in all ways and forever.”

T. Carlos “Tim” Anderson – I’m a Protestant minister and Director of Austin City Lutherans (ACL), an organization of partners in Austin, Texas working together to serve low-income individuals and families.

Check out any of my books – Just a Little Bit More (2014), There is a Balm in Huntsville (2019), and There is a Balm in Wichita Falls (2024).

Check out any of my books – Just a Little Bit More (2014), There is a Balm in Huntsville (2019), and There is a Balm in Wichita Falls (2024).

January 1, 2025

Blessed Dryuary – Again

Nine years ago during Christmas, our daughter Alex shared her upcoming new-year endeavor : “Dryuary.” I had never heard the word before but understood it instantly – dry January. Alex, a vegetarian and daily exerciser, proceeded to converse with me and her mother, Denise, about the wisdom of bodily and mental detox after December’s season of excesses. It made an impression. A year later, Denise and I jumped on the Dryuary bandwagon and we thanked Alex for role-modeling the idea. Alex yet practices Dryuary as do other family members. This year will mark Denise’s and my eighth time to do Dryuary together.

As 2024 winds down, I especially look forward to Dryuary’s hiatus on alcohol. Denise and I have wine with most dinners . . . but purposely incorporating change into one’s habits gives an opportunity for perspective enhancement. Dryuary not only gives a mild cleanse to one’s psychological and physical states, but also a chance to reset them.

I’m in resetting mode and, to boot, there are good historical reasons that make the case for Dryuary and its invitation to reclaim the wisdom of moderation.

The winter solstice, December 21 – the shortest day in the Northern Hemisphere – has a deep cultural history related to the rhythms of year-end harvest. For millennia, the period preceding and following the solstice (what we moderns call October, November, December, and January) has been the time of gathering in harvests, slaughtering for fresh meat, and enjoying the products of fermentation, beer and wine. December was and is the time for excess – eating, drinking, celebrating, leisure – a time to enjoy labor’s rewards at year’s end.

Our modern-day December holiday season with gifts and the exaltation of consumerism, rich food and libations, and celebrations simply follows suit. Santa Claus, with his round belly and deep laugh, is the iconic representative of our modern season of excesses. (For those wondering about how December’s religious aspect – namely, the baby Jesus – fits into this topic, I cover that here.)

Have you ever put on a few pounds during the winter holidays? Have you ever signed up for a gym membership in January? If so, you’ve experienced the natural rhythms of this time of the year. There’s nothing wrong with occasional excesses. The hundreds of seeds produced by my garden’s basil and cilantro plants when they flower – in anticipation of next season’s reproduction – is a prime example of the goodness of excess.

When excess, however, becomes a way of life – addiction being excess’s most devious manifestation – problems multiply for individuals so afflicted and for the society in which they live. Eating, drinking, consumerism – all necessary parts of the human enterprise – are best done in moderation. This is the basic theme and message of my first book, Just a Little Bit More.

As we age, we slow down and our habits – both the good and bad ones – become more engrained. Youth’s ability to shrug off mistakes and pivot to new possibilities has diminished. Hopefully, for those of us in the aging mode, the wisdom of the years has accumulated and produced effective strategies for dealing with the vagaries of life. As we’ve heard it said: “For everything there is a season, and a time for every matter under heaven.”

I have, God willing, good plans for 2025: multiple house projects, weekly golf, writing, and continuing the meaningful social ministry work I’m able to do with fantastic partners. Dryuary helps me get a head start on these good ambitions where needed.

Even though Twitter is awash with Dryuary bashing – “I made it 8 hours into this year’s #Dryuary before a bottle of reserve Rioja was calling my name . . . ” – I’m not persuaded otherwise. The pendulum has swung away from December into blessed Dryuary. I raise my glass of iced hibiscus tea with fresh mint to the new year!

T. Carlos “Tim” Anderson – I’m a Protestant minister and Director of Austin City Lutherans (ACL), an organization of partners in Austin, Texas working together to serve low-income individuals and families.

Check out any of my books – Just a Little Bit More (2014), There is a Balm in Huntsville (2019), and There is a Balm in Wichita Falls (2024).

Check out any of my books – Just a Little Bit More (2014), There is a Balm in Huntsville (2019), and There is a Balm in Wichita Falls (2024).

December 18, 2024

Merry Christmas, Charlie Brown

I was almost four years old when the CBS network debuted A Charlie Brown Christmas on December 9, 1965. From the living room of a house that my parents rented on Grand Avenue in St. Paul, Minnesota, I most likely watched its premiere. My dad was a second-year seminary student at the time, and, like many of his classmates, a big fan of Charles Schulz and his Peanuts comic strip. As my dad completed his education and began his career as a pastor and chaplain – prompting a family move to Portland, Oregon, a return to Minneapolis-St. Paul, and then a permanent relocation to the Chicago area – Christmas seasons for our family consistently centered upon snow, lights, a tree, presents, church, and plenty of anticipation. Watching A Charlie Brown Christmas, a show that incorporated all of these themes, was a high point of each Christmas celebration in my childhood home as our family grew to include my younger brothers and sister.

A generation later, my wife, Denise, and I lived in Houston with our three young children where I worked as a pastor. A cherished copy of A Charlie Brown Christmas was prominent in our VCR tape collection alongside copies of Disney classics that the kids watched over and again. As Christmas 1992 approached, it occurred to me that I needed more than the VCR copy of the Peanuts’ gang Christmas. I had to get a copy of the soundtrack. Those wondrous bits of jazz piano, bass and drums that undergirded the animated TV special beckoned me. I had heard its notes sway and its chords swing from my earliest days. There had to be a recording of these songs where the musicians stretched out.

These were pre-Amazon days. The CD era was cresting, but even so, it wasn’t until I went to a fourth or fifth “record store” (that’s what we called them back then) that I found a cooperative store manager who promised to order me (from an inventory catalog pulled down from a shelf) a CD of the Vince Guaraldi Trio’s A Charlie Brown Christmas.

Bingo – Guaraldi and his bandmates stretched out magnificently, matching my expectations.

The next few Christmas seasons, I purchased additional copies of the CD and gifted them to family and friends. Then, in 1995, it was my turn to preach the Christmas Eve sermon at the church, Holy Cross Lutheran, I served in Houston. There was no question as to what I’d do for the message that year: a recapitulation of A Charlie Brown Christmas. It was a bit of a risk – telling a child’s tale for one of the largest worshipping crowds of the year. But I had the blessing of my pastoral colleague Gene Fogt and – even though the animation has no adult characters – I knew Charlie Brown’s story wasn’t just for kids.

The opening scene of the special features Charlie Brown confiding to his buddy Linus van Pelt: “I just don’t understand Christmas, I guess. I like getting presents . . . but I’m still not happy. I always end up feeling depressed.”

Writer Charles Schulz wonderfully develops a twenty-two minute animated homily from this starting confession to convey his own sense of Christmas’s true meaning: not the glitz and glitter of over-commercialization – which ultimately doesn’t deliver on its promise – but human and divine solidarity through the birth of a child. “For unto you is born this day in the city of David a Savior, which is Christ the Lord. And this shall be a sign unto you; ye shall find the babe wrapped in swaddling clothes, lying in a manger,” Linus tells Charlie Brown, quoting Luke 2.

A recently retired USAF colonel, Rolf Smith, was visiting the congregation that Christmas Eve with his family. He loved the sermon (as he told me later) and returned to Sunday worship services in the new year. As we got to know each other, I learned that Rolf had spearheaded the launch of “innovation” as a corporate strategy for the air force. To him, recasting A Charlie Brown Christmas for a sermon was “highly innovative.” That spring, he and his spouse, Julie, joined the church.

Another congregant, however, expressed her disdain to me about the sermon. She deemed a rendering of “a cartoon” as inappropriate for Christmas Eve worship. It wasn’t until a few years later that I discovered that a family member of hers struggled mightily with depression. The message was too close to home. For Christmas Eve worship, I surmised, she had not wanted any mention of depression and its effects.

Producer Lee Mendelson, Peanuts’ creator Charles Schulz, and animator José Cuahtomec “Bill” Melendez

Producer Lee Mendelson, Peanuts’ creator Charles Schulz, and animator José Cuahtomec “Bill” MelendezCharles Schulz, from his Sebastopol, California studio, collaborated with producer Lee Mendelson and animator Bill Melendez after Coca-Cola agreed to underwrite the special in the summer of 1965. Adhering to a fast-tracked schedule, Schulz and Melendez drew out 13,000 stills for the animation. Mendelson, having met and worked with the Grammy award-winning Guaraldi the previous year, commissioned the jazz pianist to record the soundtrack. A children’s choir from an Episcopal church sang for two of the tracks. Mendelson himself wrote the lyrics to Guaraldi’s tune Christmas Time is Here, now covered by hundreds of musicians the world over.

Peanuts’ piano players: Schroeder and Vince Guaraldi

Peanuts’ piano players: Schroeder and Vince GuaraldiA Charlie Brown Christmas is now playing its 60th Christmas season, and still going strong even for new generations.

When my son, Mitch, who was born in 1991, comes home to see us at Christmas, one of his first requests after hugging his mother is to hear some Christmas music – “the Snoopy and Charlie Brown disc.” I always oblige – he’s heard it every Christmas since he can remember. Lucky guy.

T. Carlos “Tim” Anderson – I’m a Protestant minister and Director of Austin City Lutherans (ACL), the social ministry expression of a dozen ELCA (Evangelical Lutheran Church in America) congregations in Austin, Texas. I’m the author of There is a Balm in Huntsville: A True Story of Tragedy and Restoration from the Heart of the Texas Prison System (Walnut Street Books, 2019). Readers describe it as “compelling,” “inspiring,” and “well written.”

I’m also the author of Just a Little Bit More: The Culture of Excess and the Fate of the Common Good (ACTA-Chicago, 2014), which traces the history of economic inequality in American society. Reviewing Just a Little Bit More, journalist Sam Pizzigati says, “Anderson, above all, writes with a purpose. He’s hoping to help Americans understand that an egalitarian ideal helped create the United States. We need that ideal, Anderson helps us see, now more than ever.”

October 6, 2024

In the Presence of Wounded Healers

A “wounded healer” leverages their own experiences of pain and tragedy to help others heal from theirs. Originally coined by psychologist Carl Jung, the term was further popularized by theologian Henri Nouwen in his 1972 book of the same name.

I’m fortunate to have spent valuable time, while working on two book projects, in the presence of wounded healers who are active in the field of restorative justice. These seasoned wounded healers – whether crime victims or, unexpectedly, perpetrators – showed me ways of healing with which I was unfamiliar. Like a bluebonnet that grows and produces its blooms from a crack in the pavement, healing can spring forth from unanticipated sources.

In 2017 while doing the initial research for the book projects, I interviewed an Austinite named Ellen Halbert. This wounded healer told me, “Every time I share my story, I heal a little bit more.” I immediately sensed that her words would guide my subsequent research and writing.

Ellen Halbert and T. Carlos in 2019

Ellen Halbert and T. Carlos in 2019Revenge, at its most basic level, is a strategy for human survival. When a tragic event or hurtful person has caused us pain, the option to strike back lurks. Revenge says, “Don’t ever do that to me again.” Revenge-themed movies like “Carrie” and “Rambo” strike chords that are deeply anchored in the human psyche. But, quite often, there is a heavy price to pay for choosing revenge – such an act can transform a crime victim into a perpetrator, and vengeance can beget more violence.

The biblical counsel “‘Vengeance is mine,’ says the Lord,” urges adherents to choose options other than revenge. Religious systems do some of their best work when they mitigate the primal urge for vengeance in situations of wrongdoing, and encourage the victimized to seek alternatives.

Our legal or retributive justice system – laws, cops, courts, jails and prisons – is a necessary part of our social contract, and the first option in situations of serious wrongdoing.

The legal system, however, does not primarily concern itself with healing. “Repairing the harm done by crime – beyond what happens in the courtroom” is a good working definition of restorative justice. The practices of restorative justice, many have discovered, offer the best options for healing in the aftermath of wrongdoing.

Typically, restorative practices utilize face-to-face encounters between adversaries in safe settings in the presence of support personnel. It’s not a “mediation” – some type of compromise understanding about the wrongdoing – but an opportunity for the perpetrator, after hearing out the victimized person, to be accountable for what they’ve done. Oftentimes, when a wronged person sees that the one who caused their pain has taken responsibility for what they’ve done, healing emerges. Restorative practices do not necessarily involve forgiveness and reconciliation, but can if desired by the participant who was originally victimized.

In 1986, Ellen Halbert was brutally attacked by a drifter who left her for dead. She was fortunate to physically survive the ordeal. Years later, she experienced emotional healing (she didn’t meet with her imprisoned attacker because he was unrepentant) by sharing her story publicly at crime victims’ rights events. “It was all I had,” she told me. “When I told my story, a sense of power and control [about her crime victimization] came over me like never before.”

She was consequently the first crime victim appointed – by Governor Ann Richards – to the Texas Board of Criminal Justice and she helped introduce restorative justice programs to the massive Texas criminal justice system. Later, she worked alongside Travis County DA Ronnie Earle as the office’s Victim Services liaison, directing victim-offender dialogues prior to sentencing, one of the early efforts in the nation of a public prosecutor’s office using restorative principles.

Ellen Halbert is now retired, but her work and the telling of her story have brought healing to thousands.

Many wounded healers, like Ellen Halbert, are advocates for restorative justice principles which help repair the harm produced by wrongdoing and have the power to pacify the ingrained human tendency toward revenge.

T. Carlos “Tim” Anderson – I’m a Protestant minister and Director of Austin City Lutherans (ACL), an organization of churches in Austin, Texas working together to serve low-income individuals and families.

September 5, 2024

There is a Balm (Also) in Wichita Falls

I’m grateful to say that my new book is out. Written in the same style as There is a Balm in Huntsville, this book highlights the stories of two valient crime-victim survivors, Ellen Halbert and Linda White. I got to know these two increbible women while doing research for Huntsville.

Their victimizations were separate but simultaneous. Later, their paths converge. Theirs is a story of restoration and healing, and I’m honored by their trust in me to share their story with you.

I’ll be at Austin-area churches this fall and into 2025 sharing the light of this story. There is a Balm in Wichita Falls is available wherever you purchase books, including Amazon.

There is a Balm in Wichita Falls: The Healing Journeys of Mr. White and the Ninja LadyWipf & Stock: Resource Publications (2024)ISBN: 979-8385223787