Allison Rohan's Blog

December 25, 2016

Merry Christmas!

Hello, my dear friends! I hope you and your family are having a lovely Christmas. I am blessed to be home with my entire family, gathered from opposite coasts.

This won't be a long post, because writing emotive blog posts is not what Christmas is about. Suffice it to say that I am grateful for each and every one of you, my friends, and that I'll be back with a book review hopefully before New Year's.

Merry Christmas!

From Pinterest

From Pinterest

This won't be a long post, because writing emotive blog posts is not what Christmas is about. Suffice it to say that I am grateful for each and every one of you, my friends, and that I'll be back with a book review hopefully before New Year's.

Merry Christmas!

From Pinterest

From Pinterest

Published on December 25, 2016 08:25

November 7, 2016

Falling Leaves

From my bed, I can see a sliver of pure blue sky through the window. The leaves of my myrtle tree are so red they're almost purple. The colors are quite magical together.

I have bronchitis. I am lying in my bed, where I have been for three days now. My art history midterm is in forty-five minutes, and even though I have a doctor's note excusing my absence, I keep having pseudo-guilt for not being there. Fortunately, my university regards difficulty breathing as an excellent reason for not attending an exam.

I have not written on this blog for a while now. College requires adjustments. Some days it feels like a dog I have taught to heel; other days it feels like a slavering monster that has eaten my sketchbook, my writing notebook, and has been chewing on my lungs for a few days now.

The worst news is that some demon has possessed my library account and is not letting me request books from my sickbed. So instead I watched four seasons of Parks and Recreation in four days like a reasonable sick person.

Convalescing in bed is dangerous because, while half of my brain is dedicated to Netflix, the other half is browsing the multitude of book websites online. In the past two sentences, I have spent three dollars on books. Send help.

So, here I am! Bed-ridden, maybe. Bronchitis-afflicted, perhaps. But back in the blogging world? Yes.

I have bronchitis. I am lying in my bed, where I have been for three days now. My art history midterm is in forty-five minutes, and even though I have a doctor's note excusing my absence, I keep having pseudo-guilt for not being there. Fortunately, my university regards difficulty breathing as an excellent reason for not attending an exam.

I have not written on this blog for a while now. College requires adjustments. Some days it feels like a dog I have taught to heel; other days it feels like a slavering monster that has eaten my sketchbook, my writing notebook, and has been chewing on my lungs for a few days now.

The worst news is that some demon has possessed my library account and is not letting me request books from my sickbed. So instead I watched four seasons of Parks and Recreation in four days like a reasonable sick person.

Convalescing in bed is dangerous because, while half of my brain is dedicated to Netflix, the other half is browsing the multitude of book websites online. In the past two sentences, I have spent three dollars on books. Send help.

So, here I am! Bed-ridden, maybe. Bronchitis-afflicted, perhaps. But back in the blogging world? Yes.

Published on November 07, 2016 08:08

September 6, 2016

How to Decorate a Dorm Room (in Three Easy Steps!)

Step one: Start a Pinterest board. It should look something like this.

Or this.

Or this.

Step two: spend $9867678986 on dorm decorations.

Step three: leave most of them at home because you don't have the deep inner strength needed to face carrying them up a bazillion stairs.

Anyway. Here's the final product.

Before I say anything else, I have to fangirl a little about my dorm. It has crown molding. And beautiful real floors, and beautiful yellow walls, and a gigantic window looking out on the oak tree-lined quad. I. Love. My. Dorm.

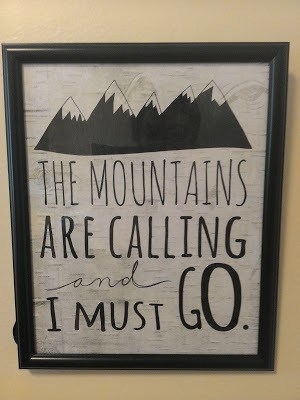

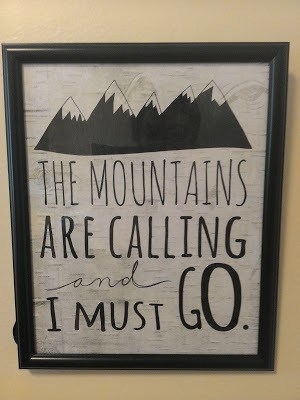

Immediately on your right is the dressing room, where I prepare my flawless daily outfits. As you may notice, there's some artwork. Here's the first:

It's a quotation by John Muir, the famous explorer. I love its adventurous spirit and wanderlust. (Text: the mountains are calling, and I must go.)

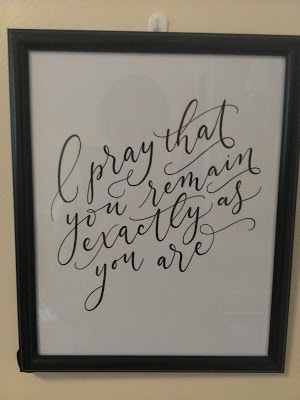

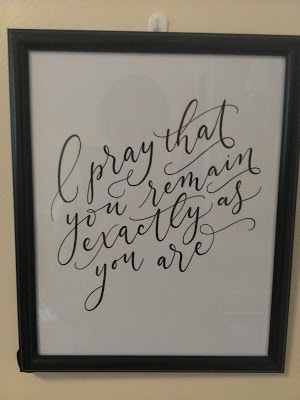

This quote is from a song written for Beauty and the Beast when it became a Broadway musical. The original phrase:

No matter what the pain,We've come this far.I pray that you remainExactly as you are.

I love having a daily reminder in my room.

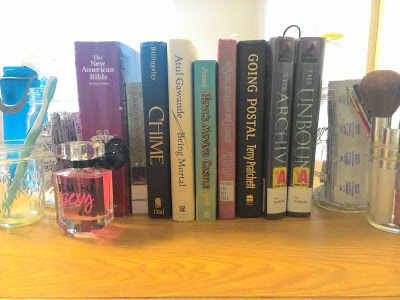

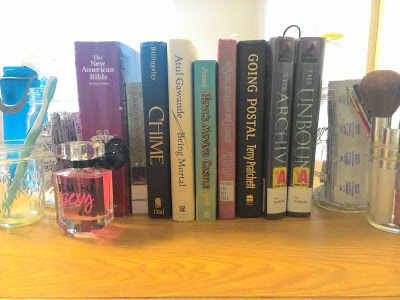

Here are my books! I have since added quite a few more, including a beautiful copy of Grimm's Fairytales, illustrated by Arthur Rackham (my favorite illustrator).

Likewise, I have since added more art to the wall above my bed. It seems a little sad and bare in this picture. And hopefully, they'll be even more to come!

Beneath my bed is my modest kitchen.

Here's my desk. It is absolutely this neat everyday. Yeah. Totally.

Remember the big, lovely window I promised? Here it is.

And that's my dorm!

I really am loving college. For those who don't know, I'm a double major in English and Classics. I'm brushing up on my Middle English and Latin this semester, which is terribly fun. I love the girls on my hall, too. So far we've watched the Lego Movie, the Emperor's New Groove, and Shrek. During the scene in Shrek where Fiona sings to birds, one of my neighbors turned to me and said, "That's you, Allison."

I'm off to seek my fortune.

Or this.

Or this.

Step two: spend $9867678986 on dorm decorations.

Step three: leave most of them at home because you don't have the deep inner strength needed to face carrying them up a bazillion stairs.

Anyway. Here's the final product.

Before I say anything else, I have to fangirl a little about my dorm. It has crown molding. And beautiful real floors, and beautiful yellow walls, and a gigantic window looking out on the oak tree-lined quad. I. Love. My. Dorm.

Immediately on your right is the dressing room, where I prepare my flawless daily outfits. As you may notice, there's some artwork. Here's the first:

It's a quotation by John Muir, the famous explorer. I love its adventurous spirit and wanderlust. (Text: the mountains are calling, and I must go.)

This quote is from a song written for Beauty and the Beast when it became a Broadway musical. The original phrase:

No matter what the pain,We've come this far.I pray that you remainExactly as you are.

I love having a daily reminder in my room.

Here are my books! I have since added quite a few more, including a beautiful copy of Grimm's Fairytales, illustrated by Arthur Rackham (my favorite illustrator).

Likewise, I have since added more art to the wall above my bed. It seems a little sad and bare in this picture. And hopefully, they'll be even more to come!

Beneath my bed is my modest kitchen.

Here's my desk. It is absolutely this neat everyday. Yeah. Totally.

Remember the big, lovely window I promised? Here it is.

And that's my dorm!

I really am loving college. For those who don't know, I'm a double major in English and Classics. I'm brushing up on my Middle English and Latin this semester, which is terribly fun. I love the girls on my hall, too. So far we've watched the Lego Movie, the Emperor's New Groove, and Shrek. During the scene in Shrek where Fiona sings to birds, one of my neighbors turned to me and said, "That's you, Allison."

I'm off to seek my fortune.

Published on September 06, 2016 03:00

August 15, 2016

Movie Review: Spirited Away, by Hayao Miyazaki

I don't like buying movies. It boils down to the same reason I don't like buying books before I've read them. If I finish it and don't like it, it's either back to the used bookstore, or I'm stuck with it.

I don't like buying movies. It boils down to the same reason I don't like buying books before I've read them. If I finish it and don't like it, it's either back to the used bookstore, or I'm stuck with it.With books, the solution is simple: go to the library. But if you're like me, your library doesn't supply movies. If I can't find it on Netflix or Amazon, I have two choices: buy the movie, or go without.

This struggle is worse because movies usually cost more than books. And it's worst of all with Miyazaki movies, which you can order now from Disney for the low price of $30 and your soul.

So when I heard of this must-see, delightfully fairytale-savvy movie, did I pawn my antique book collection? Did I sell my hair? Did I wait at the crossroads at midnight to cash into some soul money?

No. I did without. For years.

(Tangential note: the greatest thing about getting older is that I can make dramatic statements like that and they're actually true. Tangent out!)

That is, until Amazon lowered the price to $20. My resolve crumpled, and I snatched it up. It's a great deal. I even get to keep my soul.

Thus concludes the epic saga of my Spirited Away purchase. Now, enjoy the review.

Ten-year-old Chihiro feels her life is over when her family moves to the countryside, far away from her friends and school. But when her parents imbibe food meant for spirits and are transformed to pigs for their greed, Chihiro must navigate the tricky politics of the spirit world to change them back. Selling her name in exchange for a job, Chihiro, now renamed Sen, becomes a bathhouse attendant. Armed with only bravery, courtesy, and questionable allies, she must barter for her parents' freedom and her own.

Ten-year-old Chihiro feels her life is over when her family moves to the countryside, far away from her friends and school. But when her parents imbibe food meant for spirits and are transformed to pigs for their greed, Chihiro must navigate the tricky politics of the spirit world to change them back. Selling her name in exchange for a job, Chihiro, now renamed Sen, becomes a bathhouse attendant. Armed with only bravery, courtesy, and questionable allies, she must barter for her parents' freedom and her own.(To avoid confusion, Chihiro and Sen are different names for the same character.)

First and foremost, I must compliment the exquisite storytelling of Spirited Away. Mr. Miyazki uses the "pantsing" plotting method, wherein he improves much of the plot. Although I must take his word at it, this seems almost impossible when I marvel at the extreme deliberateness of every plot element. I can tell that Miyaki is a student of fairytales.

Although western folklore traditions are visible in the narrative-- especially when crossing the river of the dead, when Chihiro must force herself not to look back, in the style of Orpheus-- most of the imagery and symbolism comes from eastern mythology. The movie takes place in a sort of mirror-image universe, the nighttime spirit world, supplied by the Japanese tradition of leaving food and houses for the spirits.

The excellent plotting method of Spirited Away segues well into another element of the movie: the character development. Chihiro begins the movie very much a child whose whole way of life was ripped away. She is popularly described as sullen and bratty. Perhaps it is become I am young, but her behavior was much more sympathetic to me. She has little reason to be happy.

Emotional credibility aside, this extreme provides an excellent contrast for her progress throughout the movie. Losing her family and way of life and working in backbreaking conditions oddly suits Chihiro. It teaches her humility. It shows her the value of courtesy. By the end of the movie, when she is called upon to save the bathhouse from the ominous visitor No-Face, the courage and integrity she shows are completely believable after her emotional journey.

This struggle brings me to the darkest issue of the movie: the character No-Face.

When taken only in the context of the movie, No-Face makes absolutely no sense. His otherworldly shape resembles no other character in the movie. In his natural state, he is incapable of dialogue. We learn little of his motivation and even less of his origin. In fact, the only true desire he shows is for Chihiro, now named Sen.

Perhaps to combat this lack of detail, Mr. Miyazaki commented, somewhat ambiguously, that Spirited Away has to do with-- of all things-- sex. It took some digging and a second watching to understand what he meant, but I now feel prepared to have an opinion on it.

Historically, bathhouses were disreputable establishments that sold sex as much as a spa experience. The first time I watched it, I did not pick up on this at all. The second time through, I became aware of certain elements indicative of the bathhouse's purpose.

To be clear, Spirited Away is not by any stretch of the imagination a graphic movie. But the knowledge that Miyazki intended it to have double meaning did color my second viewing and answer

Why are they here?a few questions. It explains, for example, why Chihiro is at least a decade younger than the other female workers in the bathhouse. It also explains the presence of several dozen women workers who seemingly have no purpose.

Why are they here?a few questions. It explains, for example, why Chihiro is at least a decade younger than the other female workers in the bathhouse. It also explains the presence of several dozen women workers who seemingly have no purpose.And this darker element leads back to the presence of the character, No-Face. As his name suggests, he literally has no face, only an expressionless mask that does not even correctly indicate his features. He is the ultimate blank slate, which perhaps explains why he reacts so violently once inside the bathhouse.

No-Face goes from being a passive but essentially sweet character to a greedy, carnivorous beast upon entering the bathhouse. Chihiro even audibly notes this change, describing him as "crazy". No-Face is the most enigmatic character of the movie.

I think he represents a lot about the spirit of refusing to compromise, a persistent theme throughout Spirited Away. While her parents glut themselves, Chihiro refuses to eat a single bite. When the bathhouse workers accept even a single nugget of gold, it lowers their defenses and sets them up to be devoured by No-Face. Only Chihiro, who will not accept it, is totally safe.

I adore this picture.

I adore this picture.So does the atmosphere of the bathhouse effect No-Face. He, as a blank slate, cannot enter the lustful environment of the bathhouse and remain untainted by it. Only when he parts completely with it, and remains far away, can he return to his benevolent state.

You cannot eat half the forbidden fruit and remain whole. You cannot accept dishonest coin without becoming dishonest yourself. You cannot sacrifice your ideals-- ever-- without becoming something worse.

I think this ties in a lot to Chihiro's interactions with her parents, way at the beginning of the movie. All of her growth as a character takes place without them. They do not behave well as parents; most of their interactions with Chihiro are condescending and degrading. They also demonstrate a lack of wisdom by eating food for spirits. Only when they are removed from Chihiro can she grow into her full potential. It is another example of how your environment can effect you in Spirited Away.

Before I close the curtain on the sometimes uncomfortable elements of physicality and lust in Spirited

Away, I will say that I was somewhat uncomfortable with the main romantic relationship. Considering the age of the participants, it felt like an awful lot of hand-holding and touching. But it was not a major element of the movie.

Away, I will say that I was somewhat uncomfortable with the main romantic relationship. Considering the age of the participants, it felt like an awful lot of hand-holding and touching. But it was not a major element of the movie.Spirited Away is a beautiful, complicated, and sometimes disturbing movie. The theme of anarchy and confusion appears in the art, which is often lurid and chaotic. That does not mean it is not also lovely in its wildness. But sometimes it came across as overly raucous to me-- just as the story of Spirited Away, and many of Miyazaki's movies, crosses my line of comfort sometimes.

There are many compliments I could give to conclude this review. Suffice it to say that Spirited Away inspired me to write a thousand words.

Lin: What's going on here?

Kamaji: Something you wouldn't recognize. It's called love.

Don't look back.

Published on August 15, 2016 03:00

August 11, 2016

YA Tropes I Hate: The Other Girl

Welcome to the last post in the YA Tropes I Hate, readers! If you haven't read these yet, do give the first three a try:

1. YA Tropes I Hate

2. Angry Girls

3. Caste Systems

She's beautiful. She's popular. She's flawless in every way, except for her poisonous personality.

She's beautiful. She's popular. She's flawless in every way, except for her poisonous personality.

She is the Other Girl.

There are a number of theories as to why the Other Girl appears so frequently as a foil to the Angry Girl. Classically, evil often appears in the form of beauty, like the femme fatale. In YA, she has a lot to do with our preconceived notion of popular high school girls.

Mostly, though, I think the Other Girl has a lot to do with insecurity. The traits

that make her so eminently hate-able-- her beauty, her grasp of fashion and cosmetics, her social skills-- also make her exceptionally competent. She gives off an extreme aura of having her act together.

And speaking in generalities, young women-- myself included-- don't feel this way. Everyone has one aspect of their appearance that they're constantly trying to tame. Everyone, that is, except the Other Girl. She has already conquered the art of looking fabulous.

And speaking in generalities, young women-- myself included-- don't feel this way. Everyone has one aspect of their appearance that they're constantly trying to tame. Everyone, that is, except the Other Girl. She has already conquered the art of looking fabulous.

But the Other Girl's attack goes way beyond the average insecurities. It is based on a simple assumption: that readers and writers are intrinsically more insecure than other people.

This may at first glance make sense. Readers are traditionally considered socially awkward outsiders, who certainly could never master fashion or cosmetics. They identify pretty heavily with the Angry Girl. Readers would never indulge in a beauty as artificial as the Other Girl's. Instead, they have their own inner beauty that has nothing to do with hygiene or cosmetics.

This possibly explains the sheer over-the-topness of the Other Girl's dour personality. She's the antithesis to the reader.

And this is a stereotype just as narrow-minded and implausible as the Other Girl.

I am a reader and a writer, and I don't leave the house without mascara on. I have a hair-makeup-clothes board on Pinterest as well as storyboards. I know I'm not the only one like this.

Ultimately, that's the beauty of stereotypes: that they're not real.

1. YA Tropes I Hate

2. Angry Girls

3. Caste Systems

She's beautiful. She's popular. She's flawless in every way, except for her poisonous personality.

She's beautiful. She's popular. She's flawless in every way, except for her poisonous personality.She is the Other Girl.

There are a number of theories as to why the Other Girl appears so frequently as a foil to the Angry Girl. Classically, evil often appears in the form of beauty, like the femme fatale. In YA, she has a lot to do with our preconceived notion of popular high school girls.

Mostly, though, I think the Other Girl has a lot to do with insecurity. The traits

that make her so eminently hate-able-- her beauty, her grasp of fashion and cosmetics, her social skills-- also make her exceptionally competent. She gives off an extreme aura of having her act together.

And speaking in generalities, young women-- myself included-- don't feel this way. Everyone has one aspect of their appearance that they're constantly trying to tame. Everyone, that is, except the Other Girl. She has already conquered the art of looking fabulous.

And speaking in generalities, young women-- myself included-- don't feel this way. Everyone has one aspect of their appearance that they're constantly trying to tame. Everyone, that is, except the Other Girl. She has already conquered the art of looking fabulous.But the Other Girl's attack goes way beyond the average insecurities. It is based on a simple assumption: that readers and writers are intrinsically more insecure than other people.

This may at first glance make sense. Readers are traditionally considered socially awkward outsiders, who certainly could never master fashion or cosmetics. They identify pretty heavily with the Angry Girl. Readers would never indulge in a beauty as artificial as the Other Girl's. Instead, they have their own inner beauty that has nothing to do with hygiene or cosmetics.

This possibly explains the sheer over-the-topness of the Other Girl's dour personality. She's the antithesis to the reader.

And this is a stereotype just as narrow-minded and implausible as the Other Girl.

I am a reader and a writer, and I don't leave the house without mascara on. I have a hair-makeup-clothes board on Pinterest as well as storyboards. I know I'm not the only one like this.

Ultimately, that's the beauty of stereotypes: that they're not real.

Published on August 11, 2016 15:45

July 22, 2016

Book Lover Tag + Updates

Jemma from the Sherwood Storyteller tagged me! I thought it would be a lovely way to end my accidental hiatus. Thanks for tagging me, Jemma!

1. What book are you currently reading?

I've just cracked the spine of The Glorious Cause, by Jeff Shaara. I'm a history nerd, and I'd love to brush up on the Revolutionary War, but textbooks can be so boring. This novel will be a fun way to study.

2. What's the last book you finished?

A Treasury of Foolishly Forgotten Americans, by Michael Farquhar. Double-nerd! Actually, I'm doing research for a writing project. Nothing inspires me like history!

3. What's your favorite book you read this year?

Ugh, hard question! After perusing my Goodreads list, I would say either The Screaming Staircase, by Jonathan Stroud, or The Raven Boys, by Maggie Stiefvater.

4. What genre have you read the most this year?

Definitely fantasy, with a side of the classics.

5. What genre have you read least this year?

Does graphic novel qualify as a genre? If so, definitely that. I love a well-written graphic novel as much as anyone else, but I'm fussy about the art. (My taste in art is much more exclusive than my taste in writing.) The three webcomics I follow are The Silver Eye, by Laura Hollingsworth; The Dreamer, by Lora Innes; and my absolute favorite, Daughter of the Lilies, by Meg Syverud. I'm obsessed with it.

6. What genre do you want to read more of?

I'd like to read more nonfiction. I consistently forget how well-written and entertaining it can be. Whenever you attach the concept of 'improving yourself' to writing, it strikes me as less fun.

7. How many books have you read this year, and what's your goal?

I've read 82 books this year, with the rough goal of reading 100. I don't buy into number-of-books goals; it adds stress to reading. I only set one on Goodreads to track the number of books I read.

8. What's the last book you bought?

I have been very good and not bought any recently. The last book I bought was Being Mortal, by Atul Gawande. It's the summer reading for UNC Chapel Hill.

9. What books do you have out from the library?

Approximately sixty books on American history. I'm excited about this project.

10. What books can't you wait to read?

The Cursed Child, by J. K. Rowling, comes out in two weeks! Not to mention I've already reserved The Creeping Shadow, by Jonathan Stroud, and Ghostly Echoes, by William Ritter.

UPDATES!!

I've been squashed getting ready for school. I've bought dorm supplies, signed up for classes, gave notice at work, and am ready to move in-- let me check my phone timer-- twenty-six days, not that I'm counting. I'm a declared English major, but I plan on switching to the classics or double-majoring.

Good things, all. But it does put me seriously behind in blogging. I know I've said this before, but guys? I promise I'll blog more during the school year, when I have a reliable schedule.

Anyway, I tag Hannah at the Writer's Window, Ghosty at Anything, Everything, Emma Clifton at Peppermint and Prose, and Sarah at Dreams and Dragons.

Published on July 22, 2016 08:51

July 6, 2016

Of the Wood: Part Four

Alas! the final chapter. For those of you who haven't yet begun my retelling, Of the Wood, start here! For those of you who have, I'd like to tell you about the final element of this story: the heroine, Elizabeth.

I knew right away that I wanted Elizabeth's character to drive the plot. After all, the story takes place in a sleepy village. There is no quest, no coveted magic object, no conquest-bound overlord a few counties over. I wanted this to be a deeply personal story about the place-- this magical wood that connects different worlds in its shadowy waters-- and this confused, unhappy girl who inherited an ancient position just as the world was coming into its modernity. This is, above anything else, the story of Elizabeth. (Its original title was Elizabeth of the Wood, which I changed to Of the Wood for reasons still obscure. I'm thinking about changing it back. Thoughts? I also considered Wychwood and Under the Wood.) (Fun fact part deux: Elizabeth's original name was Evienne before she became so resolutely English, and Anaïs was originally Laetitia before I decided on a theme for the Faire names.)

So I rolled up my sleeves and dove into the character development.

And hit a wall. Almost immediately.

I have a theory as to why I struggle so much with characters. I am a reserved person. I infrequently answer direct questions about myself, and when I do, I generally give a cursory answer. (I blame my Myers-Briggs personality profile for this.)

Which makes creating believable characters difficult for me, because the only tried-and-true way I have found is to foist on them whatever nastiness is currently in my life. I like to keep this nastiness private, and the thought of sharing it makes me want to hide under my covers. Forever. (So, naturally, I'm posting it on my blog like a properly petulant teenager.)

However, I had another major character who could use some personality: Elizabeth's younger sister, Anthea.

People quite familiar with my family will observe something here. My name is Allison. I have an older sister, whose name is-- well, for the sake of her privacy, suffice it to say it is a classical English name that begins with an E. Those who know my sister and I personally may realize that both of our personalities play a prominent role in this story, passed between the characters of Elizabeth and Anthea. I am meticulously organized with a family background in accounting, whereas my sister is more assertive than I. My sister is an excellent musician, but I'm the one who sings. If we weren't sisters, people would probably call the cops on us during one of our fights. But at the end of the day, like Elizabeth and Anthea, we still love each other!

My sister probably isn't reading this. I don't think she ever reads my blog.

Love you too, sis.

Anyway. On with the story.

Seven:

The music stopped.The dance whirled to a halt.The fragile, spun-glass thing that was her mind crashed off its pedestal and shattered on the floor. “Who are you?” she managed to say, because she did not believe in miracles, and one was holding her cold hands in his warm ones and smiling at her like Lochinvar at his sweetheart’s wedding. “Elizabeth,” he said quietly, and he was smiling until he thought he would break with the joy of it. “I’ve come—“ He didn’t finish, because she leaned up and kissed him. It was a shockingly inappropriate thing to do at one’s wedding to another man. The townsmen would talk. She didn’t care. She did not care at all. “Please don’t say anything,” she said quietly. “Because I’ve just been handed a miracle. And I d-don’t see how this can be r-r-real—“ “I don’t, either,” he said softly. He reached up and wiped away the tears on her cheek. “But Elle”—he grabbed her hand in his warm, living one—“it is.” He glanced over her shoulder, and something tightened in his face. “For about five more minutes. Elle, the Faire are here.” “I know,” she whispered. She was rattled by joy and shock, but she forced her brain through its paces. “How can they be here?” “Anaïs says—“ “Anaïs!” “It’s a sort of long—“ “That harpy!” “She’s not, really,” he said desperately. “She’s just—it’s complicated—she says the Faire are dying. There’s too much iron and disbelief here, and hardly any magic left. They need us, Elizabeth. They’re coming back tonight, using your curse as the pathway. So. What’s the plan?” “You always came up with the plan! Why am I supposed to—“ “Excuse me.” Elizabeth dropped Abelard’s hand guiltily. “Fulgence,” she wanted to say, “I’m terribly sorry, but I can’t possibly marry you because my true love is back from the grave, and he hasn’t drowned, and we’re going to marry and live happy ever after, yes?” She almost said it. She wanted so badly to say it. But she couldn’t, she realized. There were times when the truth was all you could give. And there were times when the truth was far too extraordinary and time-consuming, and too unbearably real for words. And there were some people, like Fulgence, who spent their whole lives looking for a prettier, simpler lie, because they wanted prettier, simpler, uncomplicated lives. She opened her mouth to speak, but he beat her to it. “Elizabeth,” he said. “I don’t mean to frighten you. But this room seems to be eliding with the Faire Court.”

“Anaïs!” Abelard hissed, ducking through the crowd. He glanced up into masked faces. All had the square angularness of the Faire, but he needed one in particular. “Anaïs!” “Be quiet,” she whispered back, dragging him into the dance. Her green skirt billowed around them as they spun. “All right. Not going to according to plan.” “We don’t know what to do.” “She’ll know when the time is right,” Anaïs snapped. “Well, it had better be right in the very near future!” She tossed her head but didn’t pull away as they danced. Abelard watched the Faire over her shoulder. They hadn’t moved yet; they were still dancing. Things would be all right as long as the Faire kept dancing… His eye landed on another couple in the throng: Elizabeth and Fulgence. They were dancing in the same, half-focused manner as Anaïs and Abelard; she gazed up into his face, and they both talked rapidly and almost silently. Fulgence’s eyes flicked over her sleek head and watched the dancers. The same way Abelard did. He stopped dancing. Anaïs stumbled, tripping on her skirts, and two other couples nearly collided with them. “Sorry!” he said. “Ah—cramp. In my foot. Carry on.” “What is it now?” Anaïs said snappishly. She was never this short-tempered, never this out of control. She was afraid, Abelard realized, and his breath almost stopped. “After you pulled me from the bog, you said I had a gift,” he whispered, dancing. As long as the Faire still danced… “You told me I could see the Faire, and that I would need this to save Elizabeth.” “Yes, but do we have time—“ “Fulgence can see the Faire, too.” She didn’t answer. Her face was solemn behind her forest-green mask. Abelard’s heart sank. “You don’t know if I’ll save her.” He had stopped dancing again, but they were on the edge of the crowd, so it bothered no one. He felt his thin, fragile eggshell of hope crumple into airy nothing. “The future never reveals itself that fully,” Anaïs said at last. She wouldn’t look at him. “Not even to me. I only know that she can be saved, and I will provide every opportunity for someone to do so.” She gave him a hard look. “Even if he’s isn’t you.”

“Explain,” Elizabeth said. “Now.” “I was awoken early this morning by a woman in my bedroom,” Fulgence said. “She said if I wanted to save you, I had to leave now.” He sniffed. “It was rather inconsiderate of her, seeing as I got here hours early and haven’t had any call to save you yet—“ “What did she say?” Elizabeth demanded. “She said the Faire hated your family and would be at the wedding tonight. She touched my face and said I would be able to see them. And”—he sounded nauseous—“I can see them, Elizabeth. They’re horrible.” He broke off as Abelard burst through the crowd, Anaïs scarcely a step behind. “Hello, Anaïs,” Elizabeth said coolly. “It’s been a long time.” “I gather,” Anaïs said. “What were you playing at, saying my name over and over? I could tell it was you. No one else knew to do it.” Elizabeth blushed. “I wanted to hurt you,” she said, feeling a twinge of shame. “I wanted you to suffer. And I remembered what you said, how the Faire need belief because they’re only as real as we let them be. And I remembered how saying a word over and over again makes it meaningless. So I did it to you.” She swallowed. “I’m sorry.” “It made my time in my mother’s prison much harder.” Anaïs grunted. “It was clever, at least. You’re forgiven.” “And you,” Elizabeth said, eyes flashing. She gazed up into Abelard’s face and thought, this is wrong. Everything was so wrong. They should have time together, time to celebrate their love. But they didn’t have time. They’d never been given much of it.“How long do we have?” Elizabeth asked, instead of words of radiant love. “The ball always ends at midnight,” Fulgence observed, looking deliberately at the clock above Abelard’s head. “And it is your wedding, after all.” Abelard tried to ignore the bitter irony in his tone. “But what if I don’t get married?” she said. Abelard glanced around the ballroom, at the swirling, dancing Faire. “I don’t think they care,” he said. “I think it’s gone far enough already.” “So I’m going to prick my finger on a spindle soon,” Elizabeth said, turning pale. “And sleep for a hundred years.” “No,” Abelard said firmly. “I’m not going to let that happen to you.” “Elizabeth, go to the stables,” Fulgence said, as calmly as he could. He and Abelard stood side by side: one fair, the other dark. One big and towering, the other small and slender. “Take a horse, and ride to my home. My family will take care of you.” “Don’t be ridiculous,” Elizabeth said. “This is my own kettle of fish. I’ll boil in it if I have to.” That hit a chord, somewhere in the deep, primordial part of her, the part that had been sitting patiently in the tower all evening, turning the problem over in her hands and spinning. “Kettle of fish,” she said aloud. Not fish. Eels. Her gaze landed on the banquet table, and sure enough, there was a platter of eels in wine sauce. It was, impossibly, steaming. There are times when the story takes over, and I’m not writing it anymore—it’s writing me. Like the force of the story is so great it can tell itself. It only needs me to hold a pen. Your story isn’t over yet. All right, Elizabeth thought. If this were a ballad, how would it end? There would be hints along the way, clues dropped at every turn. And even if she had missed them, the deeper, older part of her had been patiently gathering them and now held them up for her inspection. Ballads were predictable creatures, once you’d sung them long enough that they’d gotten into your blood. They might seem random and insensible, but they weren’t, really; they were perfectly logical, as long as you knew what rules they were following. And it was a rule in ballads that there were always second chances, but they only came once. Elizabeth knew she could save the town. She knew she could save herself, if she tried to. And she knew the solution would be simple and poetic and that she was holding it her hands already, and she just couldn’t see it. And then she remembered the last rule of ballads: they never wasted anything. Every detail was important. And there was one massive detail in Elizabeth’s life that hadn’t been resolved yet. Slowly, she raised her eyes. They met Anaïs’s. She knew exactly what to do. The great clock in the hall, the clock that Maelӱs had made with Anaïs’s help and this night in mind, pointed only a few minutes ‘til midnight. “We’re too late,” Fulgence whispered. “No,” Elizabeth said, and she laughed. “We’re too early.” Because the final rule of ballads was that they always came full circle. And they practically sang themselves, so that the singer only needed to hold the tune. “Fulgence, Abelard,” she said. “Thank you so much for trying to save me. But I don’t need it now.” She spun around, hiked her rosy skirts above the knee, and ran up the stairs to the tower.

Eight:

She locked the door behind her, fingers shaking on the key. She’d had nightmares like this, where things were rushing up the stairs and she had to struggle to lock the door before they reached her. Never in her most fevered nightmare had they been Abelard and Fulgence. “Hey—what—Elle, you’ve gone and locked the—“ “Elizabeth,” Fulgence said sharply, voice muted by the wood. “Unlock the door.” “Can’t. Sorry, boys,” Elizabeth called desperately over her shoulder. She picked up her skirts and hurried to the spinning room. There, turning serenely with only a hiss of gears, were the Spinning Jeannies. Papa’s pride. The only things that kept the town from sinking into a gloom of magic and despair. “All right, how do you turn these things off,” Elizabeth muttered, hunting through the controls. She was embarrassed that she had no idea how they worked. She still did all her spinning on a treadle wheel because it was wonderfully distracting. Her fingers couldn’t work the latches and gears. “Elizabeth!” Fulgence yelled, pounding on the door. Abelard had gone silent. “Open the door!” “I can’t!” Elizabeth said hysterically, and she was crying after she had promised herself that this wouldn’t be hard, it wouldn’t hurt. It did hurt. She saw now more clearly than ever that she had never really intended to leave the town with Fulgence. It would be like cutting off her hand to escape the manacle. Maybe in a hundred years she would be glad she’d done it, but she still wouldn’t have a hand. She cried over the machinery, because she didn’t know how to stop it. She cried for herself and Abelard, but mostly she cried, ridiculously and inexplicably, for the tower room, because she knew she couldn’t stay there much longer. “You won’t be able to turn them off in time,” someone said. If Elizabeth had a fingers-width of space left in her heart, she would’ve been surprised. But she didn’t. So it felt perfectly natural when she looked up to Anaïs. She had left her mask downstairs, and her face was raw and bare like a boiled egg. “Anaïs,” Elizabeth said, and her voice cracked. “I’m sorry, Elle,” she said, and Elizabeth realized that she was uncomfortable. She, Anaïs, the Faire princess. “I’m really sorry.” It was a day for miracles. There was a lot they would’ve liked to say. In a way, they did, only silently—or perhaps it all came out in Anaïs’s words: “There’s a shovel in the closet.” “I’ll get it,” Elizabeth said, rising. “No, I will,” Anaïs said. “You have something else to attend to.” Her eyes were unfocused, past Elizabeth. Elizabeth steeled herself. “All right,” she said nervously. She ran to the door and called, “Abelard? Fulgence?” “Elle, if you could possibly hurry with whatever you’re doing in there, because the Faire have—“ She unlocked the door, and Abelard tumbled out in a graceless heap. He was, she realized with a pang for lost time, slightly shorter than her; she could see the top of his dark head. “Stopped dancing,” he finished. “We three need to have a talk, and I’d like it to be very sensitive and kind and worthy of forgiveness, but I don’t have time,” Elizabeth said, pushing them into her sitting room. “First of all, Fulgence, I’m sorry, you’re a good man, but I can’t marry you, because I’m in love with Abelard.” “Sorry,” Abelard said. She had been dreading this part of the conversation. She did not know how he would take it. She could see in the shape of his eyes that he was both surprised and not, that he had both seen it coming and never believed it would come to pass. He shrugged. It was not quite so graceful a gesture as he might’ve wished. “Ah, well,” he said, after too long a pause. “It’s been fun, Elizabeth. But there are plenty of fish in the sea.” “Yes,” Elizabeth said, “and I wish you the very best of luck with them, and would you mind exiting via the window?” “Best of—what?” “There’s ivy on the wall. You should be able to climb safely; I know Anthea’s done it when we were littler.” “Oh. Right. Didn’t know you wanted me to leave quite so—“ “That is not the reason, and you know it, Fulgence,” she snapped, feeling close to tears again. She had never felt so much as she had in the past day. “I’m about to make a terribly unfair decision for all the people in this keep, and I don’t want to make it for you, too. So—you’re a wonderful friend, and I’ll miss you, but the very best thing you can do now is return to Brittany and forget this ever happened.” He lumbered to the window and was gone. “Did I miss something?” Abelard said. She had forgotten something. Elizabeth froze and thought hard. What had she forgotten? Someone tapped on the door. “Elizabeth,” Anthea said. “Could you open the door?” “Anthea!” Elizabeth cried. “What are you doing?” “Dying.”

She realized that the events thus far had been a game. A warm-up match. The Faire had shown their hand: they had her parents. They had her lover. They had her curse. She’d thought they had played their entire hand. But they had one ace left, the one that could’ve ended the game at any time but that they’d saved for last. She didn’t move as Abelard darted to the door and carried her in. Her little figure in white. Her little ice maiden. The white was red and red all over, but it couldn’t be Anthea’s blood, because Anthea was made of ice and ice didn’t bleed… Anthea’s dance partner had carved the roast. She sat down in a billow of pink skirts and moved so that Anthea’s head rested on her lap. She looked down into that serene face, white as paper except for red, still as death but for a fluttering of butterfly wings at the throat. It was like life had been a dream, and she had woken up. Like a veil had been lifted from her eyes and she saw light. This was real. This was truth. There had never been anything but her sitting on the floor with Anthea’s head in her lap, their dresses running with blood. Her little sister, whom she’d believed she’d hated. Whom she’d believed had hated her. “Anthea,” she whispered. Abelard was saying something to her. She didn’t pay him any mind until he reached up and slapped her. “Stop, you’ll hurt her!” she cried, and she realized she hadn’t said anything at all. But he caught her attention. “Elizabeth,” he said, “if you have any plan at all, we need it now. Please. Let me carry Anthea, and do whatever you have to do.” She had to stand. That was what she had to do. Abelard lifted Anthea out of her lap like she was the skin of a paper doll or a bird resting from flight, and Elizabeth gathered her legs under her and stood. The world did not end. It would not end for—she checked the clocks, but they were dead and gone—until midnight. However far away that was. The ball always ended at midnight. Carefully, Elizabeth slipped the dreamlike veil over her eyes again so that she could bear the moment. Anthea was hurt, yes. But she could handle that. Wasn’t that what she had always done? “Your shovel, my lady,” Anaïs said. “Thank you.” She accepted the shovel. It was heavy and glinted silver in the dull light, like a sword. It was her sword. “Anaïs, you understand that I want to destroy your people’s claim on mine, raze their holdings, and salt their fields?” “Yes, my lady,” Anaïs whispered. “I would do it, too, if I had the strength.” Elizabeth knew she had to hurry, but she asked, “Why?” “Because we were not meant for this,” she said simply. “No creature was. We were not meant to live this long or this emptily. We were not meant to have the power to move stars.” “Some would say that everything is already in perfect order.” “And I do believe that, my lady,” she said. “But we are not meant to be anymore. We must step back from this place. You must grow without us now.” She took a deep, shaking breath. “If it means anything to you, we only did it because we wanted to be loved.” “I’m sorry,” Elizabeth whispered. “And I do love you.” Anaïs glanced up. Elizabeth caught one last glimpse of her green eyes through her veil of pale hair, gleaming with something she could never say but now thought was, perhaps, humility. “Thank you,” she said, then she was gone, and the tower was empty save for Abelard, Anthea, and Elizabeth. Elizabeth took a deep breath to keep her heart from breaking. “Abelard,” she whispered, “do you know what I mean to do?” “Yes, my lady,” he said, and she could not tell what was in his gaze. “Do what you must.” “Flavie is in my household.” “I know.” “Abelard, I’m afraid. I’d just decided that I wanted to stay, and now I have to leave again. I hate to leave everything. And I’m scared.” “I’d like to tell you there’s no reason to be,” Abelard said finally. “But there will always be something for us to fear, Elle. It’s better that way. Else we’d have no reason for courage.” “Life has been unkind to us,” Elizabeth whispered. Abelard leaned forward and kissed her. “Don’t say that,” he whispered back. “We haven’t seen the ending yet.” His breath was warm against her cheek. “Do what you must. I love you.” She felt more than saw his smile. “See you in a hundred years.” And he turned away from her, to the splintering remains of the door. He set Anthea down gently on the loveseat and plucked down Papa’s sword from above the mantle, the one he had never wanted to use. It glittered red in the firelight as though already stained by blood. He gave a wordless cry and rushed from the room as, on the landing, the door splintered and gave. Elizabeth wrung the remaining strength from her muscles, holding nothing back. With a cry, she brought the shovel heavily down on the first Spinning Jeannie. It cracked and snarled as it kept spinning, splinters hurled through the room. Elizabeth stood so her body shielded Anthea. Then she raised the shovel again and, howling with bloodlust, pummeled her Papa’s pride and joy until it was useless splinters on the carpet, the room was silent, and mankind was undefended. A sliver of wood lay on the floor. Elizabeth snatched it up and, with only the smallest hesitation, drove it into her hand. It cut deeply, drawing blood. She tasted the snap and curl of magic as the curse came upon her. Her vision dimmed until the twilight looked golden like a summer’s evening. Almost overcome with weariness, she staggered over to the loveseat and curled up beside her sister, her arms around her neck, as she had when they were both little girls. Through her haze, she could hear Abelard’s cries, the ring of steel on steel, the humming of magic—but it dimmed and slowed into a lullaby. Elizabeth lay her head on the pillow beside Anthea’s. A hundred years may pass, but they would only be a moment to her. She had only to close her eyes. Then Abelard would wake her, and they would have all the time in the world. A lot could happen in a hundred years. There was so much to look forward to. There would be iron, of course; more iron than she could dream of now, heaped and strung like jewels in a dragon’s horde. And iron meant there would be no Faire, no wolves and no bog, no babies lost on winter evenings. And iron and no Faire meant progress, and progress meant wonderful medicines. It meant that people with terrible wounds would not die but would live on, healed by something far greater than magic, for when had magic ever brought life? There was a whole new world just beyond her fingertips, and in her last moment in the time wherein she had been born, Elizabeth wondered if they would have sheep there. I’m ready, she thought. I’m ready to see it. I want to see the time in which I’m meant to live.

The voice of Maelӱs’s clock sang out midnight. In her tower room above the moorland, the last Lady of the Wood fell asleep.

I knew right away that I wanted Elizabeth's character to drive the plot. After all, the story takes place in a sleepy village. There is no quest, no coveted magic object, no conquest-bound overlord a few counties over. I wanted this to be a deeply personal story about the place-- this magical wood that connects different worlds in its shadowy waters-- and this confused, unhappy girl who inherited an ancient position just as the world was coming into its modernity. This is, above anything else, the story of Elizabeth. (Its original title was Elizabeth of the Wood, which I changed to Of the Wood for reasons still obscure. I'm thinking about changing it back. Thoughts? I also considered Wychwood and Under the Wood.) (Fun fact part deux: Elizabeth's original name was Evienne before she became so resolutely English, and Anaïs was originally Laetitia before I decided on a theme for the Faire names.)

So I rolled up my sleeves and dove into the character development.

And hit a wall. Almost immediately.

I have a theory as to why I struggle so much with characters. I am a reserved person. I infrequently answer direct questions about myself, and when I do, I generally give a cursory answer. (I blame my Myers-Briggs personality profile for this.)

Which makes creating believable characters difficult for me, because the only tried-and-true way I have found is to foist on them whatever nastiness is currently in my life. I like to keep this nastiness private, and the thought of sharing it makes me want to hide under my covers. Forever. (So, naturally, I'm posting it on my blog like a properly petulant teenager.)

However, I had another major character who could use some personality: Elizabeth's younger sister, Anthea.

People quite familiar with my family will observe something here. My name is Allison. I have an older sister, whose name is-- well, for the sake of her privacy, suffice it to say it is a classical English name that begins with an E. Those who know my sister and I personally may realize that both of our personalities play a prominent role in this story, passed between the characters of Elizabeth and Anthea. I am meticulously organized with a family background in accounting, whereas my sister is more assertive than I. My sister is an excellent musician, but I'm the one who sings. If we weren't sisters, people would probably call the cops on us during one of our fights. But at the end of the day, like Elizabeth and Anthea, we still love each other!

My sister probably isn't reading this. I don't think she ever reads my blog.

Love you too, sis.

Anyway. On with the story.

Seven:

The music stopped.The dance whirled to a halt.The fragile, spun-glass thing that was her mind crashed off its pedestal and shattered on the floor. “Who are you?” she managed to say, because she did not believe in miracles, and one was holding her cold hands in his warm ones and smiling at her like Lochinvar at his sweetheart’s wedding. “Elizabeth,” he said quietly, and he was smiling until he thought he would break with the joy of it. “I’ve come—“ He didn’t finish, because she leaned up and kissed him. It was a shockingly inappropriate thing to do at one’s wedding to another man. The townsmen would talk. She didn’t care. She did not care at all. “Please don’t say anything,” she said quietly. “Because I’ve just been handed a miracle. And I d-don’t see how this can be r-r-real—“ “I don’t, either,” he said softly. He reached up and wiped away the tears on her cheek. “But Elle”—he grabbed her hand in his warm, living one—“it is.” He glanced over her shoulder, and something tightened in his face. “For about five more minutes. Elle, the Faire are here.” “I know,” she whispered. She was rattled by joy and shock, but she forced her brain through its paces. “How can they be here?” “Anaïs says—“ “Anaïs!” “It’s a sort of long—“ “That harpy!” “She’s not, really,” he said desperately. “She’s just—it’s complicated—she says the Faire are dying. There’s too much iron and disbelief here, and hardly any magic left. They need us, Elizabeth. They’re coming back tonight, using your curse as the pathway. So. What’s the plan?” “You always came up with the plan! Why am I supposed to—“ “Excuse me.” Elizabeth dropped Abelard’s hand guiltily. “Fulgence,” she wanted to say, “I’m terribly sorry, but I can’t possibly marry you because my true love is back from the grave, and he hasn’t drowned, and we’re going to marry and live happy ever after, yes?” She almost said it. She wanted so badly to say it. But she couldn’t, she realized. There were times when the truth was all you could give. And there were times when the truth was far too extraordinary and time-consuming, and too unbearably real for words. And there were some people, like Fulgence, who spent their whole lives looking for a prettier, simpler lie, because they wanted prettier, simpler, uncomplicated lives. She opened her mouth to speak, but he beat her to it. “Elizabeth,” he said. “I don’t mean to frighten you. But this room seems to be eliding with the Faire Court.”

“Anaïs!” Abelard hissed, ducking through the crowd. He glanced up into masked faces. All had the square angularness of the Faire, but he needed one in particular. “Anaïs!” “Be quiet,” she whispered back, dragging him into the dance. Her green skirt billowed around them as they spun. “All right. Not going to according to plan.” “We don’t know what to do.” “She’ll know when the time is right,” Anaïs snapped. “Well, it had better be right in the very near future!” She tossed her head but didn’t pull away as they danced. Abelard watched the Faire over her shoulder. They hadn’t moved yet; they were still dancing. Things would be all right as long as the Faire kept dancing… His eye landed on another couple in the throng: Elizabeth and Fulgence. They were dancing in the same, half-focused manner as Anaïs and Abelard; she gazed up into his face, and they both talked rapidly and almost silently. Fulgence’s eyes flicked over her sleek head and watched the dancers. The same way Abelard did. He stopped dancing. Anaïs stumbled, tripping on her skirts, and two other couples nearly collided with them. “Sorry!” he said. “Ah—cramp. In my foot. Carry on.” “What is it now?” Anaïs said snappishly. She was never this short-tempered, never this out of control. She was afraid, Abelard realized, and his breath almost stopped. “After you pulled me from the bog, you said I had a gift,” he whispered, dancing. As long as the Faire still danced… “You told me I could see the Faire, and that I would need this to save Elizabeth.” “Yes, but do we have time—“ “Fulgence can see the Faire, too.” She didn’t answer. Her face was solemn behind her forest-green mask. Abelard’s heart sank. “You don’t know if I’ll save her.” He had stopped dancing again, but they were on the edge of the crowd, so it bothered no one. He felt his thin, fragile eggshell of hope crumple into airy nothing. “The future never reveals itself that fully,” Anaïs said at last. She wouldn’t look at him. “Not even to me. I only know that she can be saved, and I will provide every opportunity for someone to do so.” She gave him a hard look. “Even if he’s isn’t you.”

“Explain,” Elizabeth said. “Now.” “I was awoken early this morning by a woman in my bedroom,” Fulgence said. “She said if I wanted to save you, I had to leave now.” He sniffed. “It was rather inconsiderate of her, seeing as I got here hours early and haven’t had any call to save you yet—“ “What did she say?” Elizabeth demanded. “She said the Faire hated your family and would be at the wedding tonight. She touched my face and said I would be able to see them. And”—he sounded nauseous—“I can see them, Elizabeth. They’re horrible.” He broke off as Abelard burst through the crowd, Anaïs scarcely a step behind. “Hello, Anaïs,” Elizabeth said coolly. “It’s been a long time.” “I gather,” Anaïs said. “What were you playing at, saying my name over and over? I could tell it was you. No one else knew to do it.” Elizabeth blushed. “I wanted to hurt you,” she said, feeling a twinge of shame. “I wanted you to suffer. And I remembered what you said, how the Faire need belief because they’re only as real as we let them be. And I remembered how saying a word over and over again makes it meaningless. So I did it to you.” She swallowed. “I’m sorry.” “It made my time in my mother’s prison much harder.” Anaïs grunted. “It was clever, at least. You’re forgiven.” “And you,” Elizabeth said, eyes flashing. She gazed up into Abelard’s face and thought, this is wrong. Everything was so wrong. They should have time together, time to celebrate their love. But they didn’t have time. They’d never been given much of it.“How long do we have?” Elizabeth asked, instead of words of radiant love. “The ball always ends at midnight,” Fulgence observed, looking deliberately at the clock above Abelard’s head. “And it is your wedding, after all.” Abelard tried to ignore the bitter irony in his tone. “But what if I don’t get married?” she said. Abelard glanced around the ballroom, at the swirling, dancing Faire. “I don’t think they care,” he said. “I think it’s gone far enough already.” “So I’m going to prick my finger on a spindle soon,” Elizabeth said, turning pale. “And sleep for a hundred years.” “No,” Abelard said firmly. “I’m not going to let that happen to you.” “Elizabeth, go to the stables,” Fulgence said, as calmly as he could. He and Abelard stood side by side: one fair, the other dark. One big and towering, the other small and slender. “Take a horse, and ride to my home. My family will take care of you.” “Don’t be ridiculous,” Elizabeth said. “This is my own kettle of fish. I’ll boil in it if I have to.” That hit a chord, somewhere in the deep, primordial part of her, the part that had been sitting patiently in the tower all evening, turning the problem over in her hands and spinning. “Kettle of fish,” she said aloud. Not fish. Eels. Her gaze landed on the banquet table, and sure enough, there was a platter of eels in wine sauce. It was, impossibly, steaming. There are times when the story takes over, and I’m not writing it anymore—it’s writing me. Like the force of the story is so great it can tell itself. It only needs me to hold a pen. Your story isn’t over yet. All right, Elizabeth thought. If this were a ballad, how would it end? There would be hints along the way, clues dropped at every turn. And even if she had missed them, the deeper, older part of her had been patiently gathering them and now held them up for her inspection. Ballads were predictable creatures, once you’d sung them long enough that they’d gotten into your blood. They might seem random and insensible, but they weren’t, really; they were perfectly logical, as long as you knew what rules they were following. And it was a rule in ballads that there were always second chances, but they only came once. Elizabeth knew she could save the town. She knew she could save herself, if she tried to. And she knew the solution would be simple and poetic and that she was holding it her hands already, and she just couldn’t see it. And then she remembered the last rule of ballads: they never wasted anything. Every detail was important. And there was one massive detail in Elizabeth’s life that hadn’t been resolved yet. Slowly, she raised her eyes. They met Anaïs’s. She knew exactly what to do. The great clock in the hall, the clock that Maelӱs had made with Anaïs’s help and this night in mind, pointed only a few minutes ‘til midnight. “We’re too late,” Fulgence whispered. “No,” Elizabeth said, and she laughed. “We’re too early.” Because the final rule of ballads was that they always came full circle. And they practically sang themselves, so that the singer only needed to hold the tune. “Fulgence, Abelard,” she said. “Thank you so much for trying to save me. But I don’t need it now.” She spun around, hiked her rosy skirts above the knee, and ran up the stairs to the tower.

Eight:

She locked the door behind her, fingers shaking on the key. She’d had nightmares like this, where things were rushing up the stairs and she had to struggle to lock the door before they reached her. Never in her most fevered nightmare had they been Abelard and Fulgence. “Hey—what—Elle, you’ve gone and locked the—“ “Elizabeth,” Fulgence said sharply, voice muted by the wood. “Unlock the door.” “Can’t. Sorry, boys,” Elizabeth called desperately over her shoulder. She picked up her skirts and hurried to the spinning room. There, turning serenely with only a hiss of gears, were the Spinning Jeannies. Papa’s pride. The only things that kept the town from sinking into a gloom of magic and despair. “All right, how do you turn these things off,” Elizabeth muttered, hunting through the controls. She was embarrassed that she had no idea how they worked. She still did all her spinning on a treadle wheel because it was wonderfully distracting. Her fingers couldn’t work the latches and gears. “Elizabeth!” Fulgence yelled, pounding on the door. Abelard had gone silent. “Open the door!” “I can’t!” Elizabeth said hysterically, and she was crying after she had promised herself that this wouldn’t be hard, it wouldn’t hurt. It did hurt. She saw now more clearly than ever that she had never really intended to leave the town with Fulgence. It would be like cutting off her hand to escape the manacle. Maybe in a hundred years she would be glad she’d done it, but she still wouldn’t have a hand. She cried over the machinery, because she didn’t know how to stop it. She cried for herself and Abelard, but mostly she cried, ridiculously and inexplicably, for the tower room, because she knew she couldn’t stay there much longer. “You won’t be able to turn them off in time,” someone said. If Elizabeth had a fingers-width of space left in her heart, she would’ve been surprised. But she didn’t. So it felt perfectly natural when she looked up to Anaïs. She had left her mask downstairs, and her face was raw and bare like a boiled egg. “Anaïs,” Elizabeth said, and her voice cracked. “I’m sorry, Elle,” she said, and Elizabeth realized that she was uncomfortable. She, Anaïs, the Faire princess. “I’m really sorry.” It was a day for miracles. There was a lot they would’ve liked to say. In a way, they did, only silently—or perhaps it all came out in Anaïs’s words: “There’s a shovel in the closet.” “I’ll get it,” Elizabeth said, rising. “No, I will,” Anaïs said. “You have something else to attend to.” Her eyes were unfocused, past Elizabeth. Elizabeth steeled herself. “All right,” she said nervously. She ran to the door and called, “Abelard? Fulgence?” “Elle, if you could possibly hurry with whatever you’re doing in there, because the Faire have—“ She unlocked the door, and Abelard tumbled out in a graceless heap. He was, she realized with a pang for lost time, slightly shorter than her; she could see the top of his dark head. “Stopped dancing,” he finished. “We three need to have a talk, and I’d like it to be very sensitive and kind and worthy of forgiveness, but I don’t have time,” Elizabeth said, pushing them into her sitting room. “First of all, Fulgence, I’m sorry, you’re a good man, but I can’t marry you, because I’m in love with Abelard.” “Sorry,” Abelard said. She had been dreading this part of the conversation. She did not know how he would take it. She could see in the shape of his eyes that he was both surprised and not, that he had both seen it coming and never believed it would come to pass. He shrugged. It was not quite so graceful a gesture as he might’ve wished. “Ah, well,” he said, after too long a pause. “It’s been fun, Elizabeth. But there are plenty of fish in the sea.” “Yes,” Elizabeth said, “and I wish you the very best of luck with them, and would you mind exiting via the window?” “Best of—what?” “There’s ivy on the wall. You should be able to climb safely; I know Anthea’s done it when we were littler.” “Oh. Right. Didn’t know you wanted me to leave quite so—“ “That is not the reason, and you know it, Fulgence,” she snapped, feeling close to tears again. She had never felt so much as she had in the past day. “I’m about to make a terribly unfair decision for all the people in this keep, and I don’t want to make it for you, too. So—you’re a wonderful friend, and I’ll miss you, but the very best thing you can do now is return to Brittany and forget this ever happened.” He lumbered to the window and was gone. “Did I miss something?” Abelard said. She had forgotten something. Elizabeth froze and thought hard. What had she forgotten? Someone tapped on the door. “Elizabeth,” Anthea said. “Could you open the door?” “Anthea!” Elizabeth cried. “What are you doing?” “Dying.”

She realized that the events thus far had been a game. A warm-up match. The Faire had shown their hand: they had her parents. They had her lover. They had her curse. She’d thought they had played their entire hand. But they had one ace left, the one that could’ve ended the game at any time but that they’d saved for last. She didn’t move as Abelard darted to the door and carried her in. Her little figure in white. Her little ice maiden. The white was red and red all over, but it couldn’t be Anthea’s blood, because Anthea was made of ice and ice didn’t bleed… Anthea’s dance partner had carved the roast. She sat down in a billow of pink skirts and moved so that Anthea’s head rested on her lap. She looked down into that serene face, white as paper except for red, still as death but for a fluttering of butterfly wings at the throat. It was like life had been a dream, and she had woken up. Like a veil had been lifted from her eyes and she saw light. This was real. This was truth. There had never been anything but her sitting on the floor with Anthea’s head in her lap, their dresses running with blood. Her little sister, whom she’d believed she’d hated. Whom she’d believed had hated her. “Anthea,” she whispered. Abelard was saying something to her. She didn’t pay him any mind until he reached up and slapped her. “Stop, you’ll hurt her!” she cried, and she realized she hadn’t said anything at all. But he caught her attention. “Elizabeth,” he said, “if you have any plan at all, we need it now. Please. Let me carry Anthea, and do whatever you have to do.” She had to stand. That was what she had to do. Abelard lifted Anthea out of her lap like she was the skin of a paper doll or a bird resting from flight, and Elizabeth gathered her legs under her and stood. The world did not end. It would not end for—she checked the clocks, but they were dead and gone—until midnight. However far away that was. The ball always ended at midnight. Carefully, Elizabeth slipped the dreamlike veil over her eyes again so that she could bear the moment. Anthea was hurt, yes. But she could handle that. Wasn’t that what she had always done? “Your shovel, my lady,” Anaïs said. “Thank you.” She accepted the shovel. It was heavy and glinted silver in the dull light, like a sword. It was her sword. “Anaïs, you understand that I want to destroy your people’s claim on mine, raze their holdings, and salt their fields?” “Yes, my lady,” Anaïs whispered. “I would do it, too, if I had the strength.” Elizabeth knew she had to hurry, but she asked, “Why?” “Because we were not meant for this,” she said simply. “No creature was. We were not meant to live this long or this emptily. We were not meant to have the power to move stars.” “Some would say that everything is already in perfect order.” “And I do believe that, my lady,” she said. “But we are not meant to be anymore. We must step back from this place. You must grow without us now.” She took a deep, shaking breath. “If it means anything to you, we only did it because we wanted to be loved.” “I’m sorry,” Elizabeth whispered. “And I do love you.” Anaïs glanced up. Elizabeth caught one last glimpse of her green eyes through her veil of pale hair, gleaming with something she could never say but now thought was, perhaps, humility. “Thank you,” she said, then she was gone, and the tower was empty save for Abelard, Anthea, and Elizabeth. Elizabeth took a deep breath to keep her heart from breaking. “Abelard,” she whispered, “do you know what I mean to do?” “Yes, my lady,” he said, and she could not tell what was in his gaze. “Do what you must.” “Flavie is in my household.” “I know.” “Abelard, I’m afraid. I’d just decided that I wanted to stay, and now I have to leave again. I hate to leave everything. And I’m scared.” “I’d like to tell you there’s no reason to be,” Abelard said finally. “But there will always be something for us to fear, Elle. It’s better that way. Else we’d have no reason for courage.” “Life has been unkind to us,” Elizabeth whispered. Abelard leaned forward and kissed her. “Don’t say that,” he whispered back. “We haven’t seen the ending yet.” His breath was warm against her cheek. “Do what you must. I love you.” She felt more than saw his smile. “See you in a hundred years.” And he turned away from her, to the splintering remains of the door. He set Anthea down gently on the loveseat and plucked down Papa’s sword from above the mantle, the one he had never wanted to use. It glittered red in the firelight as though already stained by blood. He gave a wordless cry and rushed from the room as, on the landing, the door splintered and gave. Elizabeth wrung the remaining strength from her muscles, holding nothing back. With a cry, she brought the shovel heavily down on the first Spinning Jeannie. It cracked and snarled as it kept spinning, splinters hurled through the room. Elizabeth stood so her body shielded Anthea. Then she raised the shovel again and, howling with bloodlust, pummeled her Papa’s pride and joy until it was useless splinters on the carpet, the room was silent, and mankind was undefended. A sliver of wood lay on the floor. Elizabeth snatched it up and, with only the smallest hesitation, drove it into her hand. It cut deeply, drawing blood. She tasted the snap and curl of magic as the curse came upon her. Her vision dimmed until the twilight looked golden like a summer’s evening. Almost overcome with weariness, she staggered over to the loveseat and curled up beside her sister, her arms around her neck, as she had when they were both little girls. Through her haze, she could hear Abelard’s cries, the ring of steel on steel, the humming of magic—but it dimmed and slowed into a lullaby. Elizabeth lay her head on the pillow beside Anthea’s. A hundred years may pass, but they would only be a moment to her. She had only to close her eyes. Then Abelard would wake her, and they would have all the time in the world. A lot could happen in a hundred years. There was so much to look forward to. There would be iron, of course; more iron than she could dream of now, heaped and strung like jewels in a dragon’s horde. And iron meant there would be no Faire, no wolves and no bog, no babies lost on winter evenings. And iron and no Faire meant progress, and progress meant wonderful medicines. It meant that people with terrible wounds would not die but would live on, healed by something far greater than magic, for when had magic ever brought life? There was a whole new world just beyond her fingertips, and in her last moment in the time wherein she had been born, Elizabeth wondered if they would have sheep there. I’m ready, she thought. I’m ready to see it. I want to see the time in which I’m meant to live.

The voice of Maelӱs’s clock sang out midnight. In her tower room above the moorland, the last Lady of the Wood fell asleep.

Published on July 06, 2016 03:00

July 5, 2016

Of the Wood: Part Three

Hello, readers! Welcome to the third part of my retelling, Of the Wood. If you're lost, pop back to this post to start at the beginning!

I told you yesterday how those strange, lovely little border ballads inspired the plot and particularities of this story. Today I'd like to tell you of an adventure that tied these elements together into the final part of the story, the climax.

I love dancing. I love dancing with other people, especially when it's an actual dance, and we're all not just jumping and flailing about.

I love it most when it is a costume ball. I got to attend one last summer, at-- you guessed it-- Governor's School, when James Joyce's strange poem and the even stranger border ballads were swimming around in my head. I wore a black dress and a silver mask shaped like a crescent moon.

It. Was. Magic.

All my friends were there, turned weird and unfamiliar in the masks and half-light. We had lemonade and cheap cookies, turned to nectar and ambrosia in the candlelight. (There were no candles, but there was still candlelight, such was the extreme magic of the evening.) We were dancing in the dining hall with the chairs pushed aside. My feet were bare and stuck to the disgusting carpet. It was still magical.

And thus I learned the third part of my story. Like any good fairytale, it concluded with a ball. But it would be a ball in costume, with the guests disguised.

Enjoy.

Five: