Grayson Taylor's Blog

June 19, 2025

This mistake is ruining your creativity

Okay, tell me if this sounds like a familiar situation: you get an idea. It’s brilliant, it’s exciting, it’s going to be your big break as a writer. You can already see the five-star reviews, hear the cheering fans as you walk onstage to accept your Pulitzer, feel the weight of your finished book in your hands.

Or maybe it’s not that dramatic; it could just be a sudden flash of inspiration.

You’re motivated, you’re excited, you’re ready to bring this idea to life. No longer will you watch from the sidelines as others write their literary masterpieces; no, you too will seize the reins of your destiny, harness the power of the muse, and ride into literary superstardom.

But then the spark begins to fade. This shiny idea starts to look more like a dusty dollar store trinket. You second-guess yourself. After all, it would be foolish to act on intuition and emotion—you need to analyze this fleeting moment of inspiration until it’s completely lost its magic, and you’ve lost your interest.

I’m sure you know someone who’s had a great idea for a story, or claimed they have, and never done anything with it. Maybe you are that person.

Here’s the thing: inspiration is cheap.

It’s great, it’s absolutely necessary, but it’s not what makes an artist an artist. The difference between an amateur who never finishes anything and a professional who consistently makes great work is the way they respond to inspiration.

You could be struck with history’s greatest idea for a novel, but if you never do anything with it, you might as well never have had it in the first place. The idea’s potential will go unrealized. And the only thing to blame is, well, yourself.

But these flashes of inspiration don’t have to be for nothing. Your ideas shouldn’t remain trapped in the confines of your mind, never seeing the light of day, never able to be enjoyed by other people.

Before we get to the cure, we need to understand the ailment.

II. The ProblemIt can feel good to get inspired, to daydream, to think about how great the story in your head would be if you really did make it into a book, to fantasize about the acclaim it would garner and the Nobel Peace Prize you would receive after your writing united the world with its undeniable brilliance. But that feeling is pointless unless it leads to action.

Imagination is the backbone of fiction, but it can also be your downfall as a writer. If you’re an artist, you probably have a pretty good imagination, and you can use it to construct a million false realities and hypothetical futures in which you’re successful and fulfilled, without ever doing the hard, practical work of figuring out the steps it takes to get there and taking them.

Coming up with ideas, designing potential book covers, drawing character art, all these things can become substitutes for doing the actual writing. Your creative urge may be satiated, but you haven’t made any meaningful progress. You’ve become addicted to ideation, not true creation.

Now, I’m not saying this from a place of total authority and detachment. I experience this, too. I’m still learning how to decrease the gap between inspiration and creation. The ratio of ideas I have to things I actually make is… embarrassing. Having written nine novels isn’t nearly as impressive when you take into account the hundreds of other book ideas I’ve done exactly nothing with.

This is something a lot of writers deal with, especially aspiring writers with a million ideas and no finished projects.

III. Creative ReflexBut there’s a solution to this problem. It’s straightforward, but that doesn’t mean it’s easy.

It’s to develop a fast creative reflex. You need to seize inspiration when it strikes you and use it to propel yourself into the creative process. Don’t wait for the idea to lose its luster. Don’t overthink it. Don’t waste time planning and daydreaming.

If you have a fast creative reflex, the time between inspiration and creation will be short. If, like me, you tend to be excessively deliberative and analytical, that response time will be much longer.

But like physical reflexes, your creative reflex can be improved by training. The best way to develop a faster creative reflex is to work on projects with a quick turnaround time. Short stories, flash fiction, short-form videos, anything you can start and finish within a few hours.

Sometimes, it pays to have a slower and more thoughtful approach to starting new projects, especially when it comes to something as big and time-consuming as a novel. You can work your way up to a longer project by quickly iterating and improving your creative reflex with shorter works.

If you want to write a novel, but you’re feeling writer’s block, one of the best things you can do is jump into writing a completely new short story. Treat it as an exercise, an experiment. Don’t overthink, just create. Do it again. And again. You’re training your creative reflex and weakening the barriers between inspiration and creation. Soon enough, you’ll find you’re ready to start writing that novel.

Not every artist has a fast creative reflex. Or if they do, it may just be for a season. At different times in your life, you may find this approach to be invaluable, or completely unnecessary. But if you find yourself creatively stuck, this is what it takes to get unstuck.

It’s important to act quickly on inspiration because it’s a fleeting and unreliable thing. Of course, if you’re serious about writing, you’ll have to write even when you don’t feel inspired. But if you have that feeling, if you catch a glimmer of that spark, why wouldn’t you use it for all it’s worth? It makes the process more exciting, and it usually means you can produce work faster.

A moment of inspiration can be an onramp into a flow state. The flow state is something I could probably make a whole video about, but in short, it’s the neurological phenomenon of locking in on a project. You can lose track of time and work at a faster rate than usual. It’s a state every artist wishes they could be in at all times. Unfortunately, that’s not how it works, but having a fast creative reflex can help you slip into that state much more easily.

If you have an active imagination, you’ll end up with way more ideas than you can ever bring to life. The point here isn’t to pursue every creative whim that comes to you. If you did, you would end up scattered in a million directions, failing to make significant progress on any one project.

So instead, focus on one idea at a time. Choose whichever idea calls out the most loudly to be created. Whichever shines the brightest, whichever you can’t stop thinking about. It doesn’t have to be the perfect idea, it doesn’t have to be big or flashy, it just needs to speak to you.

Jump straight into making it, and forget everything else until it’s finished. Forget external incentives, forget other ideas you have, forget the sneaking suspicion this project might be an exercise in futility. Your job is to catch the spark of inspiration and hold onto it for dear life. By the end, you may find that spark has faded into a dull ember, but you must finish it. Even if it’s terrible, you must finish it. Because if you don’t, you’ll perpetually be stuck in this liminal state between inspiration and creation.

When we make note of an idea and take no further action, we’re deferring creativity to our future self. We’re assuming that they’ll have the motivation to take that seed and grow a tree out of it.

But that assumption could easily be wrong. You don’t know what state of mind your future self will be in—you don’t know what new ideas they’ll have to prioritize.

When I was younger, I had all kinds of ideas for books and films that I was really passionate about, and too much of the time, I would jot these ideas down and trust that I would eventually get around to bringing them to fruition.

Want to guess what happened to those ideas?

Nothing. They’ve sat around filling up pages in notebooks and Word Docs for years.

I wish I had spent less time planning and dreaming and more time creating. Hindsight highlights the massive difference between having ideas and executing them. Even if they didn’t turn out as masterpieces, I’m so much prouder of the projects I took the leap to make and finish than the ones that remained in the pre-production phase.

So I’m trying to learn from the past and improve my creative reflex.

I’ve spent the past five years working on my latest novel. That is… way too long, in my opinion. If those five years had been spent consistently and tirelessly working on crafting this book, that would be fine. But over the past five years, I’ve found myself stuck repeatedly, caught in the trap of analysis and overthinking.

I’m lucky that I’m still as passionate about this story as I was when I started—maybe more so, in fact—but I very easily could have lost motivation over such a long period of time. There was an entire year in that five-year period where I didn’t write a single word of the book. Granted, I was working on several novellas in the interim… but still.

If I were a less experienced writer, less sure of my ability to eventually finish it, there’s a good chance I would’ve given up. I don’t want that to happen to you. And I don’t want to go through that kind of process again.

This very piece is an example of this concept in action. I suddenly got the idea of ‘creative reflex’—a succinct way of phrasing something I’ve been thinking about lately, something I’m trying to implement in my own work. Usually, when I get an idea for a video, I’ll add it to my database of video ideas and continue with whatever I was doing. This time, in the spirit of the idea itself, I latched onto that moment of inspiration and didn’t let go. I wrote most of this piece in one sitting—or standing, technically; I was standing to write. I’m not doing a lot of fancy editing with the video. I’m shrinking the time between ideation and creation, training my creative reflex to be faster.

The ultimate goal of developing a fast creative reflex is to make creativity second nature. You’re building a habit out of getting inspired and quickly turning that inspiration into something real. You’re building momentum with smaller projects that will carry you forward into bigger ones.

The more you hone this skill, the more prolific you’ll be, and the closer you’ll get to becoming the artist you dream of being.

If you want to put this idea into practice right now—which you should—set a timer for 30 minutes and just write something. It can be the first idea that comes into your head, or one you’ve had sitting in a notebook for months. No judgement, no second-guessing, just write. It probably won’t be great. That’s fine. That’s kind of the point.

Then the next time you’re struck by a new idea you love, don’t file it away and forget about it. Pick up the pen or put fingers to keyboard and start writing.

You can watch the video version of this post here. I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments.

My latest workI’m currently editing Catalyst of Control, my dark sci-fi novel coming later this year.

June 3, 2025

How I built my dream writing studio in NYC

Have you ever wanted to design a space just for writing and creativity?

That’s the project I’ve undertaken over the past year—turning my small room into my dream writing studio.

I’m a novelist living in New York City, a place not exactly known for its spacious living quarters. So that presented a few challenges… but they do say constraints are good for creativity.

If you’re thinking about designing your own creative studio, I hope this will give you some inspiration and ideas. I’ll take you through the redesign process, and you can watch my tour of the final product here.

The Design ProcessI’ve always had a fascination with design—whether it was building cities out of LEGO, creating logos for fictional companies in my books, or reorganizing my room.

When it comes to my room, I’ve had to balance practicalities—a bed, space for clothes, a desk for studying—with my various creative passions. I’m a writer, a reader, a filmmaker, a content creator, an occasional composer, and an avid LEGO builder. Over the years, I’ve redesigned the room several times in pursuit of the perfect setup with enough space for all those aspects of myself.

But it wasn’t until early last year that I embarked on a true reimagining of the entire room. I was 18, and with adulthood came a new sense of creative freedom and agency. I wanted to put my fledgling interior design skills to the test with an ambitious project: creating my dream writing studio.

The first thing that desperately needed to change was the wall color. This room was divided in half, with one side a sky blue and the other a light tan. If you’ve seen any of my videos, it’s pretty obvious I kinda like blue. Tan… not so much. Especially since I filmed videos on that side of the room, and the color provided little contrast against my skin. I wanted something a little more… me.

I hunted for the right color and finally found it—Bold Blue. Bingo.

But I wasn’t just going to paint the walls. I wanted a new layout entirely. So I pulled out my trusty graph paper and sketched out some options.

I also designed some mockups in Canva of what I wanted my filming setup and primary workstation to look like. I wanted this redesign to bring more style to the space. Yes, I wanted my room to be functional, but I also wanted it to reflect my aesthetic sensibilities. I wanted it to inspire me.

The style I was going for was something of a cross between dark academia and minimalism. Now, if you know anything about those styles, you’ll know they’re very different. Dark academia is about texture and ornate designs. Minimalism is about simplicity and a lack of clutter. They’re pretty far apart on the design spectrum, but I tried to find a balance between the two, since I love aspects of both.

Once I was happy with the plan, I found a new desk and bookshelves, then got to work painting.

One issue I quickly ran into was that an entire strip of my wall had been damaged by a leak during a heavy rainstorm a few months prior. I’m sure someone handier than I could have made it look better, but I did the best I could at the time. It’s still a little rough. Let’s say it adds character.

It’s also worth noting that I was making daily short-form videos during this project. Having my room in complete disarray made that more challenging. One video I filmed sitting on the floor against a half-painted wall. You make do with what you have.

Once I was finished with the first stage of redesigning that side of the room, I turned my sights to the other half.

Since I’m short on space, I’ve had a loft bed for several years. Beneath it was a fifteen-square-foot table covered in a LEGO city I’d been building, destroying, and rebuilding again since 2018. The idea behind it was a collision of fictional universes—so you would have characters and locations from Star Wars, Jurassic Park, Harry Potter, Marvel, my own books, and dozens of other worlds combined into one city.

It was pretty fun. Unfortunately, it took up time and space I couldn’t afford. I disassembled the city to make room for an expansion to my new creative studio. Maybe it’ll return some day—only time will tell.

In its place, I planned to design a smaller space just for writing. The desk on the opposite side of the room would be my primary workstation and filming area, with a standing setup and a desktop screen ideal for editing videos. On this side would be a secondary workspace, simpler and intended primarily for writing.

Just like last time, I created some mockups of what I wanted it to look like, and found a desk and smaller bookshelves that complemented their counterparts across the room. I also chose these minimalist wall panels as a centerpiece, almost like a window I’m looking out on.

Over the next several months, I continued to make small improvements, playing around with different bookshelf layouts and replacing certain elements. Slowly but surely, my dream writing studio came to life.

The Art of Interior Design

The Art of Interior DesignI find interior design to be a fun thing to experiment with. It’s a form of self-expression. Your selection of furniture and decor, how you arrange them, tell a story about you. And the space you inhabit can influence your mindset and actions.

You don’t need to have your dream studio to create great work, but putting just a little more thought into the way you design your space helps create an environment that inspires you.

When you’re designing a space for yourself, your aim should never be to perfectly imitate something else. Sure, you can take a lot of cues from a certain aesthetic or from photos you find online, but don’t be afraid to let your unique quirks shine through.

Interior design is an art, but it’s also a form of play—much like writing. I’ve had a fun time designing this space. If you want to see it up close, watch the full video for the tour.

What would your dream creative studio look like? I’d love to hear about it in the comments.

May 20, 2025

Why you should write a book (even if no one reads it)

Hey there! Before we dive into today’s main subject, I’d like to share a behind-the-scenes update.

I’ve been working on my ninth novel, Catalyst of Control, for the past several years. It’s a dark sci-fi epic about a secretive race to develop mind control technology. It’s my most ambitious book to date, hence why it’s taken far longer to write than any of my previous novels.

I’m excited to announce that the book is now in the editing phase, and will be published this summer. If you want to be among the first to read it—for free!—you can apply to be an ARC reader here.

I’ll be sharing more about the making of the book in an upcoming video.

Why you should write a book (even if no one reads it)

Why you should write a book (even if no one reads it)Okay, here’s a wild statistic: 81% of Americans want to write a book, but less than 0.1% of people ever do. When I was 7, I broke into that 0.1% by writing my first novel, and I’ve written eight more since then. And if there’s one thing I’ve learned, it’s that writing a book can change your life—even if no one ever reads it.

I could not have predicted where writing my first book would take me. It was, though I didn’t know it at the time, a turning point that set me on the path I’m on today. And it’s not because it became a bestseller or a landed me a publishing deal.

It can feel like there’s so much emphasis placed on getting published, building a following, making your writing profitable, that the benefits of simply writing a book—regardless of its success—are overlooked. In fact, I’m glad no one read my first book—well, my first several books, really.

You Can Write a BookWe’ll get to the benefits of writing a book in a moment, but first, I think it’s important to make one thing abundantly clear: if you want to write a book, you can write a book—and you already have everything you need.

You don’t have to be ‘talented’ to write a book. I wrote my first novel when I was 7, and I was a pretty normal… well, I wasn’t really a normal kid, but I wasn’t a prodigy.

I started writing because I loved reading. I devoured books, especially fantasy and sci-fi, when I was a kid, and I had a hyperactive imagination. It felt like the most natural thing in the world to try my hand at writing my own stories. I began with short stories, comic books, and plays, and then started writing a fantasy/sci-fi book when I was 7 that turned out as a full-length novel. I barely planned it—I was mostly making it up as I went along.

I hadn’t gotten an MFA or an English degree (I wasn’t even in middle school, so can you blame me?), I hadn’t read dozens of books on writing, I didn’t have any fancy software, I didn’t even have my own computer. I was just passionate and I had plenty of time on my hands.

And that’s all you need. However young or old you are, however inexperienced, passion and time are all it takes to write a book. People will tell you you need this writing app or that plotting structure or decades of life experience to draw upon, but it’s not true. At least, if you’re writing fiction, it’s not true.

It was through writing my first book that my love for the craft was cemented. After that, I just kept going, branching out into new genres and growing my skills. I wrote a novel when I was 8, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, and 15, and over the past few years, I’ve written three novellas and my ninth novel, which is coming out later this year. I’ve been making videos about writing for four years, and I’ve met hundreds of other artists as a result of my work. I’ve started a publishing company, won awards, and built a community online of other writers. None of this would have happened if I hadn’t taken the leap to write my first book. And mind you, practically no one read it, and it wasn’t all that good. Still, that one decision forever altered the course of my life.

So, obviously, writing a book can change your life in some pretty significant ways. But even if you don’t want to make this into your career, even if you don’t want to publish, even if you feel like you only have one story in you, writing a book can be transformative. Here’s why.

I. Self-discoveryIn a story, your protagonist goes on a journey. They face obstacles in pursuit of a goal, undergo change, and emerge on the other side with new skills and knowledge. Usually, they become a better person as a result of what they experience. As a writer, you go through the same journey in the process of bringing your book to life. You’ll face challenges and setbacks. You’ll learn new things and find help in unexpected places. You’ll have breakthroughs and victories.

By the time you finish your book, you’ll no longer be the same writer you were when you started. You can learn lessons and grow as a person by reading a book, but that change pales in comparison to what you can experience by writing a book.

All fiction that comes from the heart is somewhat autobiographical. Not in its plot or characters, but in the feelings it tries to evoke. To my mind, that’s what all art really is—the attempt to capture a feeling and share it with others.

When I look back at novels I’ve written, it’s like stepping into the mind of my younger self. I can see what I was afraid of, what I cared about, what I thought was cool, the feelings and lessons I deemed important enough to crystalize in words. So not only can writing a book help you learn more about who you are now, but it can also serve as a time capsule for your future self.

I’ve discovered a lot about myself through writing fiction. Not just my preference for certain styles of prose, or my undying allegiance to the Oxford comma, but the themes and ideas that matter most to me. My latest novel examines when the pursuit of control changes from a virtue, as in self-control, to a destructive vice.

Why? Because that’s something I think a lot about myself, and I wanted to explore it on the page. Through writing this book, I’ve been able to come to a better understanding of control and the ways I seek it.

Fiction allows you to externalize and dramatize philosophical debates that would otherwise remain in the confines of your mind. It can help you come to new conclusions and see things through other people’s eyes.

II. Self-confidenceWriting a book is a big, ambitious undertaking. It’s a serious challenge. Like running a marathon, it’s something that will push your limits and force you out of your comfort zone.

Yes, it can be a lot of fun, but it also requires a lot of time and effort. If you have deadlines, it’s going to require discipline. If you have standards, it’s going to require ruthless editing. There will almost certainly be times when you’re tempted to give up. But, as counterintuitive as this may sound, the fact that it’s so hard is one of the best reasons why you should write a book.

Doing hard things is how you build self-confidence. Especially if you don’t feel like you have talent, or you were told you could never accomplish anything big, writing and finishing a book might just be the proof you need to believe in yourself.

That sounds so corny, but it’s true.

III. A change of paceTaking on such a big project can also help develop skills like time management, discipline, and focus.

In an age of short-form content, instant gratification, and constant distractions, carving out the time to write a whole book and applying yourself to the process can be a challenge. Especially if you feel like you have a short attention span, it can be intimidating, but it might just be the antidote you need to the mile-a-minute world of overstimulation we find ourselves in.

Writing allows us to slow down, listen to ourselves, and dedicate time to creating something new and beautiful. We need practices like that, now more than ever.

IV. Writing skillsWriting is one of the most fundamental and important skills a person can possess. Even in a time when you can have ChatGPT write your emails for you, being able to express your own ideas articulately is invaluable. If you can write well, you can communicate well. If you can communicate well, you can go further in any field.

Improving your writing skills will help you become a better critic of other writing, a more articulate conversationalist, a more analytical and thoughtful reader.

Writing a book can teach you how to write decent prose, how to construct beautiful—or at least competent—sentences. But beyond that, it makes you learn the fundamentals of storytelling.

Stories are everywhere. They’re used to manipulate us in advertising, to teach us lessons, to sell us on certain ideas, to keep us glued to a screen or turning the pages. A deeper understanding of storytelling techniques leads to better media literacy. You can identify the underlying reasons why a plot twist felt satisfying, or why it didn’t work. You’re more aware of the storytelling tactics used by the news or marketers to influence your feelings. It’s a little like Neo seeing the Matrix.

This doesn’t mean you’ll never be fully immersed in a story again. Yes, there are times when seeing the skeleton of the story takes me out of it, but if it’s done well enough, I can still get lost and forget about picking apart the story until after it’s finished.

In short, understanding from firsthand experience how storytelling works is a valuable skill to have, wherever you go in life.

V. It starts conversationsAnother benefit of writing a book is that it makes you a more interesting person. I’m not an inherently magnetic, fascinating guy. But I cannot tell you how many times I’ve been talking with someone and mentioned that I write novels and that sparks a conversation about literature, or my writing process, or how they’ve always wanted to write a book.

Like I mentioned earlier, a fraction of a percent of people write a book, so if you’ve written one, you’ve admitted yourself into a pretty exclusive club. It’s not every day that most people meet an author. They might not remember your name, but there’s a good chance they’ll remember you wrote a book, or you’re writing one, if it’s not finished yet.

So even if no one ever reads it, your book can serve as a good conversation starter.

VI. It can inspire othersBy writing your book, you might inspire others to do the same, or to take the leap to work on another big project.

Writing a book is something so many people aspire to, but so few ever do. Part of the reason may be that they don’t know anyone else trying to. Pursuing your dreams gives other people permission to do the same. Not that anyone actually needs permission, but it can feel that way.

Authorhood is sometimes painted as something unattainable for the average person. And sure, becoming a traditionally published author is extraordinarily challenging. But writing a book? Most people can do that. It may not be very good, and it may never be read by anyone, but a finished book is a finished book.

The art of writing should not be gatekept. It’s one of the most accessible forms of human expression, and an integral part of society. Don’t let anyone tell you that you can’t be an author—with enough time and dedication, you can make it happen. When you do, you’ll show other people they can, too. You might just be the spark of inspiration that leads someone else to tell their own story.

If you’re still reading this, you probably want to write a book. Maybe you already know what it would be about. Maybe it’s just a feeling you’ve had for a long time, that you have some story to tell, even if you haven’t found it yet. If you have that dream, no matter how far-fetched or insignificant it may seem, follow it. Try writing that book.

Maybe you’ll get two chapters in and realize you hate the process—it could happen.

Or maybe you’ll find you love it. And even if your first draft is absolute garbage, you’ve discovered something you want to improve at, something you enjoy doing even when you haven’t mastered it yet. So it’s worth a shot.

I’m glad my first several novels weren’t read by many people—they weren’t great. But they certainly weren’t a waste of time. I’ve learned so much from every book I’ve written, far more than I could have by consuming advice about the craft.

And now, my ninth novel will be my first widely published book. I couldn’t have written it without having written the previous eight. Just like every other book I’ve authored, it’s been a journey and a struggle at times.

But it’s always worth it. Even if no one ever reads it, writing a book is worth it.

You can watch the video version of this post here. I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments.

RecommendationsListen: “Your House” by Mandelbro (Bartholomew Joyce), a talented musician from Paris whom I’ve had the pleasure of meeting and seeing perform several times.

Read: Slaughterhouse-Five by Kurt Vonnegut. I visited Dresden briefly last year and realized I’d never read this classic about its destruction—an oversight I’ve now ameliorated. It’s a fascinating blend of sci-fi and memoir.

Watch: Sinners, directed by Ryan Coogler. With an unlikely combination of elements—from vampires to gangsters to blues music—it’s a lot of fun, with some truly imaginative sequences.

April 1, 2025

How to write terrible dialogue

Here’s how to write terrible dialogue, in 10 simple steps.

I. Study the greats.Absorb the masterfully flat and corny dialogue of the Star Wars prequels, straight-to-TV movies, soap operas, and poorly written books. Never expose yourself to Sorkin or Shakespeare or Steinbeck. Protect yourself from the horrors of well-written dialogue, lest you pick up a thing or two from it.

Let the lazy writing wash over you. Learn from it. Imitate it. You may begin to notice the techniques these writers employ to make their dialogue so gloriously cringeworthy, such as having characters state their feelings and tell each other things they already know for the audience’s sake.

By the end of this tutorial, you will have learned several of these tactics, giving you a helpful head start. Some day, if you work hard enough, your writing too may be studied as a shining example of terrible dialogue.

II. Avoid talking to people.

II. Avoid talking to people.You don’t want to know how real people talk. If you can’t carry on a fluid conversation, you’ll be at far less risk of writing one. This fits in well with the ideal lifestyle of a writer, since you should be spending as much time as possible in isolation and darkness.

Not talking to anyone will also help limit your understanding of the world, and the varied beliefs and speech patterns of the people in it. Your characters should all sound like you. By venturing into the outside world, you risk hearing a turn of phrase or exchange that could inspire you.

The only voices you hear should be the ones in your own head.

III. Use clichés.There are so many wonderfully overused phrases to choose from. Why choose at all? Pack every one into your dialogue, and use them over and over again to really drive the point home that your characters have never had an original thought in their lives, and neither have you. If you ever find yourself thinking hard over what a character should say… you’re doing it wrong.

If you want to take this to the next level—which, of course, you do—don’t write a single original line of dialogue. Plagiarize everything. Or if that sounds like too much work, just make sure every sentence your characters speak sounds like it could’ve been plagiarized. Every line should make your reader think, “I’ve definitely heard that before.”

IV. Don’t write characters, write mouthpieces.Your characters should be as thin and flat as the paper they’re written on. Here’s a simple rule of thumb to remember: write caricatures, not characters. There should never be any tension or conflict in your dialogue. The good guys should always be right and agree with each other, and the bad guys should always be cartoonishly wrong.

Regularly stop the story to let your protagonist indulge in a self-righteous monologue so they can preach the moral of the story to the villain, or just to the readers, who, of course, wouldn’t be able to figure it out otherwise.

Your readers should be able to see you pulling the strings. They should see the characters as puppets rather than people. The end result is that they’ll be utterly uninvested and detached from the story, which is exactly what you want.

V. Be as realistic as possible, in only the worst ways.You know how a lot of real-life conversation is dull and meandering? Your job as a writer is to capture that on the page so your readers are subjected to excruciating small talk even in the escape of fiction. They should know they’re never safe from bland discourse about the weather.

End scenes as late as possible—stretch out dialogue to the fullest extent. Like all the worst real-world conversations, your dialogue scenes should feel interminable and awkward. There should be a palpable sense of time being wasted in every exchange between characters.

Filler words are a must-have in dialogue. Your characters should use so many ‘like’s and ‘um’s and ‘uh’s that they all sound like insecure teenagers.

VI. Pack in as much jargon as possible.Confuse your reader, and yourself, to the greatest extent language permits. Make your dialogue flowery and verbose to the point of incomprehensibility. If something can be said in two words, your characters should say it in two hundred. Over-explain every element of your world down to the most irrelevant detail in page after page of lifeless monologue. Use fancy-sounding words in your dialogue without understanding what they mean. Interweave perspicacious parataxis with recondite apophasis.

In fact, you can jettison the bounds of language and make up nonsense words that do nothing to further the plot or worldbuilding. Construct meaningless jargon solely to clutter the page. Your characters shouldn’t even sound human.

VII. Exposition, exposition, exposition.Exposition is when you tell the reader something they need to know about the plot or characters. Assume your readers aren’t intelligent, so you need to repeat things a lot. Remember, exposition is when you tell the reader something they need to know about the plot or characters.

Your characters should constantly be stating facts to each other, like walking Wikipedia pages that won’t shut up. Make them tell each other things they already know, in a transparent attempt to convey information to the reader alone. They’ll appreciate having it delivered to them repeatedly in such a ham-fisted manner.

Nothing should be conveyed nonverbally in your story. Pack your pages with monologues about what your characters are feeling, thinking, doing, what they’ve done, what they plan to do, what they had for lunch, what they had for breakfast, what they’re thinking about having for dinner—anything to fill the silence. You don’t want to give your characters, or your readers, a chance to breathe.

Your characters’ backstories should be explained in dialogue. Nothing should be left to the reader’s imagination—after all, it’s best to assume they don’t have one.

A bonus tip: repeat characters’ names in dialogue all the time. Your readers might forget mid-sentence who’s being spoken to, so always have your characters refer to each other by their names. Their full names, ideally. You could even throw in their role in the story.

VIII. Make all your characters sound the same.Regardless of who your characters are, where they’re from, what their history is, they should all sound identical. Avoid doing any research into vocabulary specific to a character’s profession, time period, or place of origin. All your characters, from a medieval king to a futuristic robot, should sound just like you.

If multiple characters are speaking, the reader should have no idea who’s who. None of your characters should have unique verbal tics or favorite phrases. You should be able to swap lines of dialogue between characters without anyone noticing. All your dialogue should melt together into an unvaried, flavorless, and rather repugnant soup.

IX. Abuse dialogue tags.“Said” is a beautifully simple word, which is why you should never use it. But since your characters will all sound the same, you need dialogue tags for every line they speak.

Your task is to think up the most ludicrous and needlessly circuitous ways of attributing dialogue. Don’t say your protagonist “asked a question,” say they “ponderously petitioned.” Don’t write “she said,” but “she orated.”

And to make it clear what your characters are feeling, tack on a mess of adverbs, analogies, and elaborate description. Your protagonist didn’t just “whisper”; he “susurrated faintly and quietly with a hint of deep sorrow like a melancholic wind whistling through the twisting caverns of a long-abandoned mid-to-late-eighteenth century coal mine haunted by the ghosts of child laborers.”

Allow me to provide another excellent example:

X. Avoid subtext.

“Where is the weapon?” Jack barked vociferously through gritted teeth with barely suppressed rage burning like a metaphorical fire of emotional feelings.

“Why, you mean the weapon to destroy the world I have been designing in secret for the past ten years, five months, and seventeen days?” vocalized Bob with his mouth.

“Yes,” Jack asseverated acrimoniously.

Your characters should always say exactly what they mean. No dialogue should serve more than one purpose. In fact, if you can, make your dialogue serve no purpose at all.

Melodrama is the opposite of subtext. It’s when more emotion and higher stakes are presented explicitly than are justified by the story and characters. That’s the spot you want your dialogue to land in—at least, when it’s not mind-numbingly dull.

Your characters should scream their feelings out loud. In emotional scenes, their dialogue should read like a bored psychiatrist’s report. To really make your reader feel the melodrama in their bones, crank every dial up to 11 and then some. Use exclamation points—the more, the better. Use all caps. Your dialogue should feel as vapid, overwrought, and brainless as an angry Twitter thread.

Do nothing in your story to earn these emotional outbursts. They should feel perfunctory, redundant, and over the top.

Subtext takes thought and consideration, and communicates information in interesting and engaging ways. It’s to be avoided at all costs. If your characters aren’t constantly telling the reader what they’re thinking and feeling, how is anyone supposed to follow the story? Deliver information to your reader with the subtlety of an eighteen-wheeler driving through their front door.

Happy April Fools’ Day! This is the third year in a row I’ve made a terrible writing advice video for the occasion—you can watch it here. (Last year’s was “How to be a terrible writer,” and 2023’s was “How to write a terrible novel.”) The video includes several skits giving examples of how to implement these tips—I hope they can give you a laugh or two.

March 19, 2025

What journaling every day for 2 years has taught me

I’ve been journaling every day for over two years, and it’s become one of the most important and transformative practices in my life. Here’s what it’s taught me.

I. The Power of a Daily Writing HabitOur lives and identities are shaped by our habits. The things we do every day are a reflection of who we are. The reverse is even truer—who we are is a reflection of the things we do every day. I’m a writer, not just because I say so, but because I’ve made a habit of writing.

Journaling is a low-stakes way of establishing a daily writing habit. You’ll always have something to write about, even if it’s just how unremarkable your day was, and there’s no pressure that it has to be of publishable quality.

Journaling doesn’t have to be a daily practice, although I’ve found that cadence and consistency to be the most beneficial for me.

I’ve journaled on and off for over thirteen years. When I started journaling at the age of six, I only wrote entries during certain periods I wanted to remember—trips or major events, like acting in a Broadway show. In 2017, when I was eleven, I started a new journal of daily life, the first time I’d journaled ‘regular life’ instead of a specific trip or experience. I was rather inconsistent, and only wrote 32 entries in the entire year. But it was a start.

In 2020, shortly after quarantine lockdowns in New York City began, I started a daily journal again. It felt like an appropriate time to resume. I was living through something monumental, a surreal moment in modern world history.

Over the next couple of years, I kept journaling, albeit with some large gaps. A little over two years ago, at the end of 2022, was when I started a daily journaling streak that I haven’t broken since.

And sure, missing a day here and there wouldn’t be the end of the world. But for me, it’s become a ritual. The day doesn’t feel complete, and I don’t feel like I’ve fully processed all that’s transpired, until I’ve written something about it.

II. The Practice of Documenting Your LifeLife is composed of countless memories plus the present moment. Our lives are 99.999% memory; the present, experienced moment is but the smallest remaining fraction.

One of the things that makes a life feel expansive and well-lived is a vast library of memories, awareness of the millions of big and little moments that led up to the here and now. To document your life is to capture those moments on paper or in pixels or in waveforms, creating records and relics you can look back at in the future.

Being able to read what I was thinking and doing and creating a year ago, or two years ago, or three, or four, or five, is incredible. On my dashboard page in Notion, I have a tab where I can see entries from this day in previous years. It’s fun to look back and get such a clear glimpse into the past through my writing. Every entry is a time capsule. I’m able to remember so much more of my life, even the smallest details that I would’ve forgotten had I not written them down.

It’s interesting to see how my journaling style has evolved over the years. My earliest journals were focused exclusively on recording the events of the day. (Honestly, they’re not very interesting to read.) Over the years, I started including more internal thoughts and reflections. In some physical journals, I drew illustrations to complement what I was writing about.

The older I’ve gotten, the more I’ve written about what’s happening on an internal level from day to day—my aspirations, fears, and mindset. Connecting those ideas to the actual events I’m experiencing provides a more complete picture of life in the present moment.

I think this helps develop my skills in writing fiction, too. The aim of my writing is to craft a true reflection of the fabric of life. That means including every dimension, from physical to intellectual to emotional. Great books transport us to other worlds and times, sketching them with such detail and veracity that we feel like we’re actually there, even if they’re completely fictional. That’s my overall aim in journaling. I want to be able to look back at what I’ve written in the future and feel like I’ve stepped through a time machine.

One thing I’ve added to my journaling practice in the past few months has been taking a photo every day to include in my entry. Not only am I documenting my life in writing, but I’m including a visual memento. I don’t know that a picture is worth a thousand words, but it does enhance what I’ve written about the day.

Humans are storytelling creatures. We see stories everywhere. We create them for fun, or to share how we’re feeling, or to impart wisdom to others. Our own lives are filtered through the lens of story. In documenting your experiences, you literally get to write the story of your life.

Okay, a brief aside: I don’t know how common this is among writers, but I often interpret events in my life from an overtly literary angle. Last year, I spent a month in Europe, and exactly halfway through, I got sick. On top of that, I was feeling burned out and disappointed in myself for failing to keep up making daily videos, which I’d been trying to do for 365 days straight. And you know what I thought to myself? I’ve reached the midpoint of the Save the Cat Beat Sheet. According to that story structure, I’ve been on a downward path, and after this False Defeat midpoint, things will improve on an upward path to the climax of the story.

And that’s actually how it ended up working out. Life imitates art, or art imitates life.

III. The Skill of MetacognitionMetacognition is the study of one’s own thoughts. It’s thinking about thinking. While that may sound like an ouroboros of over-analysis, it can be incredibly useful, especially to artists.

Writing a book or making art of any kind can feel like an abstract process. The more you record and reflect on that process, the less overwhelming and unknowable it begins to feel.

I find journaling to be an excellent way of documenting my creative process and contemplating how a project is going. If I’m stuck in the novel I’m working on, I can write about that in my journal and explore the reasons behind the creative block. I can follow my stream of consciousness to discover new paths I might want to take the story down. In my experience, there’s a big difference between simply thinking something through and writing it out on the page. Putting your thoughts and dreams and uncertainties into words compels you to clearly articulate concepts.

In externalizing your thoughts through journaling, you’ll be able to see how your thinking changes over time, and what ideas and issues matter most to you. For fiction writers, a journal provides perspective that better enables you to identify thematic topics that are relevant to your own life. Journaling can be an outlet to write about these big ideas, like death and justice and free will, without the filter of fiction. You can get out all your thoughts on a topic and then take only your best ideas and insights into your story.

Writing about your creative work alongside everything else going on in your life can illuminate patterns and correlations. Events and circumstances unrelated to writing can have a big impact on your art, even if the link isn’t obvious. If you’re reflecting on all aspects of your life together, it’s far easier to connect the dots. For instance, you might find your creative energy is influenced by the seasons, or that you get your best ideas when you have long stretches of time alone in nature.

Beyond your creative work, keeping a journal develops your skill of self-reflection. It makes you take stock of your life, your habits, your behavior, your decisions, your ways of thinking. Every day, you have a chance to take a look at yourself and ask how you can improve. Because almost inevitably, through journaling, you’ll come to discover things about life and about yourself—some of which you like, and some of which you very much don’t.

Using a journal as a tool for self-reflection and self-improvement is nothing new. In fact, the practice dates back to ancient times. The Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius kept a journal to reflect on his life, philosophy, and how he could improve himself. The philosopher Seneca wrote that every night, “I examine my entire day and go back over what I’ve done and said, hiding nothing from myself, passing nothing by.”

Writing about your life consistently for years is a powerful method of self-reflection. You can stumble upon realizations without even intending to. Journaling is a form of data collection—as you experience new things, you take note of the feelings and ideas they spark. More than simply thinking to yourself, writing everything out on the page forces you to confront hard truths head-on, crystalize your vision for the future, recognize what you want and don’t want. Over time, as you collect more data points, you can refine your goals and systems to better align with your values, your strengths, and the reality of the world.

It’s all well and good to want to be a bestselling author, but if you never do the work to reflect on why you want that and what it would take to achieve it, you’ll be stumbling through the dark toward a dream you don’t fully understand. Journaling builds this crucial skill of metacognition, of self-analysis, that’s needed to successfully navigate life.

IV. The Value of Beautiful WritingI take great pleasure in writing well, crafting articulate arguments and beautiful sentences, even when it’s in a journal entry that no one else will ever read. I’m not alone in this; it’s something many writers, I’m sure, can relate to.

I think there’s something special about creating beautiful things for the sake of creating beautiful things. Approaching life with artistry even when no one’s looking. It’s something uniquely human, and thus something all the more important in today’s day and age. Efficiency and utility are prized above all else. Technology is built to be as streamlined and pragmatic as possible. Everything must be cut down to a replicable form. Words must be concise and inoffensive. It’s all about economy and speed.

And look, I’m all for streamlining processes and reducing informational clutter. But for me, journaling, just like fiction writing, isn’t about utility. Writing isn’t just a communication tool. It’s an art form.

When you read private letters written by great authors, you’ll find that they put what could be seen as a completely unnecessary amount of work into writing them. They imbued their correspondences with the same care and mastery of language as their novels and poems and essays. It wasn’t efficient. But they made their words matter, even the ones that were never meant for publication. And so, decades and even centuries later, we can read their letters and find insight and beauty within.

Nowadays, that kind of unnecessarily beautiful writing is far less common. Part of that has to do with how the world has changed. We have to respond to far more messages than people in the past. Authors’ inboxes and DMs are teeming with questions and comments from readers, friends, family, businesses, and collaborators, to the point that it would be impossible to craft a lengthy response to every one of them. And of course, minimalism and efficiency have their place. Not everything you write needs to be dripping with poetic imagery.

But this idea of creating beautiful writing for an audience of one, or even just for yourself, fascinates me. Journaling is how I put that idea into practice.

Some of my favorite pieces I’ve written are contained within my journals, and in all likelihood, no one else will ever read them. That’s just fine with me. Everything you write develops your skills, and the insights you unlock in journaling can eventually make their way into the stories you share with the world.

Although I do love to imbue some of my journaling with a sense of craft and artistry, that’s not how I approach it every day. If I had the expectation that every entry would shine with poetic beauty or deep insight, I would’ve given up a long time ago. My aim is simply to document my life however I see fit and write something about every day.

Above all, a journal should be honest. Sometimes, the most honest way of journaling is spilling a loose, unedited flow of consciousness on the page. Sometimes, the most honest way of journaling is taking the time to find just the right words to skillfully paint a picture like you would in a novel or poem. Both approaches are valid. Both are necessary.

Since there’s no pressure for it to be polished or publishable, journaling can be an ideal outlet for experimentation. You can try writing in different styles and formats. My journal entries range from analytical breakdowns of how I spent every minute of my day to philosophical essays. Some are just a sentence or two. Others are thousands of words long and broken into parts.

This year, I want to get even more experimental with my journaling. Maybe I’ll try writing a poem about the day’s events, or get back to drawing illustrations to visualize what I’m writing about. The possibilities are limitless, and that’s part of what makes journaling so fun.

Over the past two years that I’ve been journaling daily, and the past thirteen years I’ve been journaling overall, I’ve learned a lot. About myself, about creativity, about the challenges and big questions of life. At this point, it’s something I can’t imagine not doing. It provides clarity in a way that little else can. In our modern era, when we’re bombarded with information and opinions from every direction all the time, clarity is more important than ever.

Through journaling, I’ve been able to get clarity on important decisions in my life. I’ve grappled with ideas that matter deeply to me. I’ve learned more about myself and my creative process. The things I’ve discovered and worked out through journaling have altered my trajectory for the better in significant ways.

Writing every day, documenting your life, reflecting on your thoughts, and creating a space for artistic experimentation can have a profound effect on the way you think, act, and write. Journaling might just change your life. It’s changed mine.

You can watch the video version of this post here. I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments.

My latest workI’m finishing the first draft of Catalyst of Control right now. If you’re interested in reading it early (and for free!), you can apply here.

RecommendationsListen: This song from Sunset Blvd. I got to see the phenomenal new Broadway production this month.

Read: The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson, a fascinating look into the science of what we’re made of.

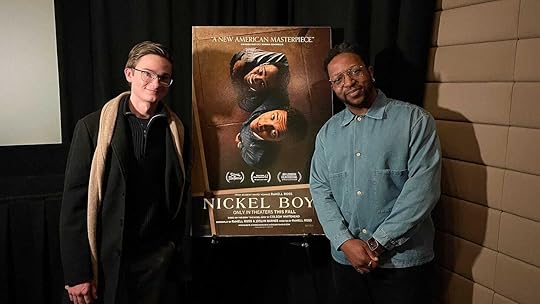

Watch: Nickel Boys, directed by RaMell Ross, a film shot in first-person perspective. I had the pleasure of speaking with its innovative cinematographer Jomo Fray at a screening last month.

February 25, 2025

The 5 steps to being a prolific writer

If you want to be a great writer, there’s only one way to get to that level, and that’s to write a lot.

I’ve written eight novels and four novellas over the past twelve years, and my goal this year is to write more than ever before.

I’m going to share with you my simple tactics for being a prolific writer. By the end, you’ll be equipped with methods to write more than you previously thought possible, without burning out or overworking yourself.

Even if you’re not a writer, these five steps can be applied to nearly anything you want to do more of this year.

Why You Should Be Prolific

Why You Should Be ProlificOkay, but first of all—why is it important to be prolific? What makes that a better goal than simply spending a year writing one great story?

It may sound counterintuitive, but working for a long time on one project might not improve your skills as much as spending the same amount of time completing several different projects. There’s a famous anecdote about a pottery class that demonstrates this fact. The class was split into two groups. One group was to focus on quality, the other on quantity. On the final day of class, the teacher graded the results, and found that all the highest-quality pieces were produced by the quantity group.

Why? By constantly iterating and learning with each successive project, the quantity-focused students improved their skills far faster than their quality-focused peers who spent all their time on a single piece. Producing a large amount of work means you get to throw more stuff at the wall and see what sticks. It compresses the feedback cycle so you can much more quickly evaluate your strengths and weaknesses as an artist.

This is one of the reasons it’s usually a good idea to write a lot of short stories before attempting to write a novel.

Now, being a prolific writer doesn’t mean you have to exclusively work on short projects. Really, it just means writing a lot of words, and that can include writing novels.

If you look at the highest achievers in almost any field, but especially in writing, you’ll find that most of them were far more prolific than their peers. They may only be remembered for one or two great books, but it often took a tremendous amount of output and experimentation to advance their skills to the level where they could write those masterpieces. Mark Twain, Charles Dickens, Agatha Christie, Stephen King, and so many other literary legends wrote dozens or even hundreds of books.

The idea of being a reclusive writer who only releases one great book every five or ten years is appealing, at least to me, but it’s important to recognize that you can’t get to that point until you’ve mastered the craft. And to master the craft, you first need to write a lot of stories. You can’t skip the chapter of prolific experimentation to get to the chapter of mastery.

And look, if you’re anything like me, focusing on prolific output isn’t the most natural thing in the world. Part of me wants to spend ages perfecting everything I write, revising and polishing for months or even years before moving on to the next project. But especially as a young artist—really, as anyone who wants to develop their skills quickly—the most important thing is producing a lot of work. Experimenting. Putting yourself out there, trying new things, and making creativity habitual. This isn’t to say that quality doesn’t matter. The whole point here is that quantity leads to quality.

Being prolific doesn’t just advance your skills. It also vastly increases your surface area for luck. The more books you write, the better the chance that one of them will be a bestseller. The more work you put out there, the better the chance that something will resonate with the right people. This is especially important if you want a career in writing. Yes, a lot of your success is luck-dependent, but every piece of work you produce is another ticket for the lottery. Luck favors the prolific.

Now let’s get practical. Here’s how to be a prolific writer in 5 simple steps.

Tactics to Be Prolific1. Set constraints.If your approach to writing a lot is telling yourself, “I’m going to write five books a year for the rest of my life!”… don’t expect it to end well.

Yes, your ultimate dream may be to write prolifically across the span of your entire life, but such an open-ended goal is overwhelming and hard to measure. Instead, set a period for prolific work, like the next twelve months, and reevaluate at the end. Treat that length of time like an experiment. Reflect on what you learned from it, and adjust your approach accordingly for the next twelve months, or however long. Most good goals have time constraints, even if the long-term aim is to establish a habit for life.

It’s important to remember that life moves in seasons. There may come a time when life circumstances make it difficult or impossible to write a lot every day. You also have natural rhythms as an artist that should be integrated into your approach to writing. You might find that writing every day isn’t right for you. But you’ll only know for sure after trying it out for a certain length of time.

Set time constraints for your experiments in prolific writing, and you’ll be less overwhelmed and better able to learn what works and what doesn’t in your approach.

2. Start simple.Don’t burn yourself out quickly. Sustainability is essential if you want to be prolific for longer than a few days.

Set an achievable goal; aim low to begin with. Whatever your metric, whether it’s words written or stories finished, your target number should push your limits, but not tip into the realm of impossibility.

I’m aiming to write half a million words this year. I was thinking about aiming for a million, but since my annual output has never reached a third of that, five hundred thousand seemed like a more achievable goal. It’s a challenge, but not such an intimidating one.

Especially in the beginning, it’s important to build flexibility into your rules. For instance, I’m counting journaling, video script writing, and fiction writing in my total word count. That means if I don’t meet my goal in one department, I can make up for it in another.

Start simple, and you can always add rules or increase your target later. Start complicated, and you’ll quickly burn out.

3. Make the time to write.Because if you don’t make the time, you probably won’t find the time.

Carve out time to write in your calendar, and protect it with your life. Maybe that’s a bit much, but you get the point.

Think about when in the week you can write. This may require cutting out time spent on social media or entertainment. But we’re not here to mess around—we’re here to write, and that takes time. Sacrifices must be made.

Don’t think that you have to find five-hour chunks of time to write. You can be a prolific writer by writing in bits and pieces. Ten minutes of downtime can be turned into ten minutes of working on your story. Your commute can be time to jot down ideas and observations. Countless writers have written books in small increments, finding ways to squeeze writing between other commitments.

Making writing a daily habit will go a long way in ensuring prolific output. Like I said before, when you’re starting out with a new goal or habit, stay flexible and aim low. Better to write a little every day than write a lot every once in a while. It’s like building a muscle. Focus on consistency over intensity.

4. Keep your why in mind.Presumably, you don’t want to be a writer just because you picked that from a list of activities at random. So what’s driving you to do this? Because the answer will be essential to keeping you on track when the going gets tough.

If you want to be prolific, you’ll need to write on some days when you really don’t feel like writing. Your why will serve as a guiding light on those days.

This isn’t just about knowing why you want to be a writer; it’s also about knowing why you want to be a prolific writer. The reasons might be similar, but not quite the same. A dedication to being prolific speaks to a drive greater than that of a casual hobbyist. Maybe you want to write a lot so you can improve faster in your craft. Maybe you want to write a lot so you have more chances of getting something published. Maybe you want to write a lot because you have a ton of ideas bouncing around in your head. Whatever your why is, discover it and keep it central as you write.

The human mind can do incredible things if it’s driven by a sense of purpose. The more intrinsic and personal, the better.

On a smaller scale, you should also know the why behind the individual projects you’re working on. Writing stories you’re not passionate about is a great way to quickly run out of steam.

Know why you want to be a prolific writer, and why what you’re writing matters to you, and you’ll know why you should persevere day after day.

5. Make it fun.If you want to write a lot, you need to enjoy writing. There are a lot of things about writing that are inherently fun—we literally get to turn fictional stories we imagine into books we can share with other people. But there are ways to make the process even more fun.

You can gamify your writing. I’ve set a daily word count goal, and every day I can see what percentage of that goal I’ve written. It’s exciting every time I hit a number higher than 100%.

You can customize your writing environment. If you have the space, set aside a specific area for writing. I have a themed writing nook in my room, which is kind of overkill, but it does get me in the mood to write.

You can listen to specific music when you write. Turning it on can serve as a trigger to get you in the right headspace. I’m prolific at creating playlists, so I have one for every story and kind of project I’ve written. Sometimes, I have specific playlists for certain characters or types of scenes.

You can try writing challenges to keep you on your toes. Try to write a certain amount of words in five minutes, or find a random prompt to use as the basis of a short story, or attempt to emulate the style of a writer you like. Remember, not everything you write needs to be published some day. Some writing can just be for fun. The more you write and the more you experiment, the better equipped you be to write something great that does get published.

Improperly managed, attempting to be prolific can be exhausting. Properly managed, done sustainably, creativity becomes a flywheel, a perpetual inspiration machine. If you set constraints, start simple, make the time to write, keep your why in mind, and make it fun, you’ll find it hard not to be prolific.

You can watch the video version of this post here. I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments.

My latest workI’ve stepped back from working on videos this month to focus on writing Catalyst of Control. I’m making good progress, and I can’t wait to share the book with you later this year.

RecommendationsListen: The soundtrack of Interstellar by Hans Zimmer. I got to see him live in concert this month, which was fantastic—I’ve been a fan for many years, and listened to many of his film scores while writing my books.

Read: The Anthropocene Reviewed by John Green. A series of reviews of various aspects of life on earth, from sunsets to the game “Monopoly” to the World’s Largest Ball of Paint, woven together in a fascinating blend of humor and memoir and philosophical contemplation.

Watch: A Real Pain, written and directed by Jesse Eisenberg. I attended a screening and Q&A with Eisenberg earlier this month, my second time seeing the film. It explores difficult themes of pain and loss through a nuanced, and often unexpectedly humorous, lens.

February 5, 2025

The most important reminder in life

How often do you think about death?

I think about it often. The end of things. The ephemerality of life. My own mortality.

That may sound dark. But facing that darkness, facing the fact that your life will inevitably come to an end one day, is one of the most important practices we can have.

The Ancient Romans had a phrase for this: memento mori. Just two words, but they held a deeper power.

Memento mori means remember death. Remember you must die. It was whispered into the ears of great leaders as they rode in triumphal parades through Rome. At the apotheosis of their careers, these two words would serve as a reminder. This moment will pass. For all the glory you gain, you can never escape the grave. All must perish.

Awareness of our own mortality puts everything in perspective. It illuminates what matters, and what doesn’t.

This reminder is especially important for anyone who creates things—for writers like myself.

If you’re a writer, or would like to understand this philosophy better, I invite you to read on.

Memento mori, memento creareAt the end of our lives, it won’t be the awards and accolades that matter. It won’t be the reviews or rejections. It won’t be the number of books we sold, or the number of followers we gained. And yet those things can seem so important in the present. We obsess over them to the point of forgetting about what truly matters.

We’re writers. We’re here to tell stories that mean something. We’re here to create. To be artists, not machines.

Memento mori reminds us of the end to come. I’ve added my own twist on the phrase, two words as a reminder of how I intend to live before that end.

Memento mori, memento creare.

Remember you will die, remember to create.

The very fact that any one of us is here is nothing short of miraculous. Life is a creative act, a recursive cycle of birth and death and birth and death across eons. As writers, we pour that creative energy back into the world, inventing universes and imagining characters and sharing stories never heard before.

For many of us, it feels like a calling. A necessity. A survival mechanism. A way of life. A lens through which we can see and begin to understand the world.

We only have so long to tell stories. How long, we cannot know. If we forget the finitude of our lives, we can slip into a fantasy of invincibility. Put off our dreams indefinitely. Wait to start writing that book until tomorrow, which becomes next week, which becomes next month, which becomes next year, until there’s no more next.

Taking the future for granted is sometimes pragmatic. But it’s an illusion of a guarantee. Hope masquerading as truth.

The truth is that no one knows when their life will end. Try as we might, humans have never been very good at predicting the future. Tomorrow is never promised. As Marcus Aurelius wrote in Meditations, “You could leave life right now. Let that determine what you do and say and think.” Let that guide how you spend your time. Let that show you what to create.

There’s a good chance you won’t know when you’ve started to write your last story. It could be the one you’re writing now.

Literary history is littered with unfinished manuscripts, cut short by the end of the writer’s time on earth. Read one, and you’ll be reminded that no writer, however great, can ever say all there is to say within a single lifetime.

But that’s not the point.

Because our lives are finite, the choice of what we create becomes infinitely more important. We can never encompass the entire human experience in our writing. We can never transpose every idea we have onto the page. We have a limited amount of time to write what matters most. Put those projects above all others.

I’ve been asked by many writers if they should write this plot or that genre. But there’s no story you should write. Remember you must die, and then ask yourself: what story matters most to me? What adventure would I regret not going on? What story would be the most fulfilling use of my limited time alive?

Then write it.

Some see creating art as leaving a legacy. Making a mark. Taking a shot at artistic immortality.

That doesn’t interest me much. Because spending my time creating things will have been worth it even if nothing I make is remembered.

Writing is a way of making sense of a strange world. Stories can make us more empathetic and understanding. Art is beautiful even if you’re the only one to witness it. In the act of creation, we connect with the world in a new way.

In a hundred thousand years, none of us will be remembered. Death, and its partner time, will see to that. But right now, in this fleeting sliver of existence, we have a chance to contribute to a much greater legacy than any individual’s. We have a chance to add our voices to the millennia-long song of human creativity. Before your hourglass runs empty, you can participate in the ongoing conversation between all art and artists. It’s an invitation that shouldn’t be ignored.

Anyone seeking to live a creative life will face obstacles. The easiest way to lose sight of what matters, to forget the clarity of memento mori, is to fall prey to distraction.

The world is full of distractions. Work and entertainment that drain the one resource no one can ever get back—time. You’re free to spend your life on them. No one will stop you.

But we have the opportunity, while we’re still here, to create something that matters. Every day, we have the choice to consume something meaningless or create something meaningful. When time is infinite, that choice hardly matters. There’s always tomorrow. Recognize that there won’t always be a tomorrow, and the choice becomes clear, the opportunity impossible to ignore.

Mortality, stared in the face, compels action. For writers, creation is that action.

As with all things, there is a balance to be found. We can’t, nor should we, spend every waking minute creating things. We must experience life to have something to say about it.

But at the end of the day, we must make time to write. Time to turn our experiences and feelings and questions into art. Knowing all the while that our time may run out at any moment.

Death can be frightening. An uncomfortable reality we ignore most days. But reckon with it, and it can point us toward a deeper and more creative life.

When we recognize how very short our time here is, we realize we have every reason to make the most of it.

Memento mori, memento creare.

You can watch the video version of this post here. I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments.

My latest workWhat I learned from journaling every day for two years.

A guide to being a prolific writer.

RecommendationsListen: “Postlude of Conclave” from the soundtrack of the 2024 film Conclave.

Read: The Three-Body Problem by Liu Cixin. An expansive and thought-provoking sci-fi tale about an alien invasion—but not the kind you might think.

Watch: Music by John Williams, a documentary about the life and work of the composer behind cinema’s most iconic scores.

January 24, 2025

A year of learning

First, a brief announcement: This newsletter has been inactive for a while, but it’s now moved over to Substack, where I’ll be writing more often. If you’re getting this email, you’ll continue to receive these newsletters in your inbox.

Whether you’ve been following me since my days as an actor, subscribed at the start of this newsletter a few years ago, or found me through my videos about writing, thank you for your support.

A year ago, I wrote about how 2023 was a year of change for me. Turning 18. Starting a publishing company. Traveling to new places. Starting to build real traction through my videos online.

2024 was also a year of change—but more than that, I would say the overriding theme was learning.

Last year, I experimented.

I tried to make a video about writing every day for 365 days (I made about 100 in a row before travel and burnout ended my streak).

I went to over a dozen creator events and writing clubs, where I met creatives of all types.

I quit social media for a month.

I collaborated on articles and videos with writers and YouTubers I’ve been a fan of for years.

I completely redesigned my room for writing and filming.

I spent a month traveling to 12 countries across Europe.

I learned important lessons (sometimes the hard way) about sustainability, traveling independently, finding creative community, and what really matters to me—plus things I didn’t expect to learn, like how to paint a room.

Another important lesson I learned this year, through talking to many creators I look up to, is that no one, no matter how successful or old or put-together, has all of this figured out. Life always has something more to teach us; anyone who thinks they have it all figured out is either delusional or unaware of how much they don’t know.

Every year is a year of learning. All the more so at my age, but I’d like to think I’ll never stop experimenting and seeking out new experiences.

This year, I intend to build off of the lessons I learned in 2024. Focusing on long-form over short-form videos. Making more time to write. Creating consistently and sustainably.

I’ll be sharing more in the weeks to come about what I’m working on now and what’s to come in 2025. In the meantime, if you have any questions or lessons from the past year you’d like to share, reply to this email or leave a comment on Substack. I’d love to hear from you.

My latest workIf you’re a writer, remember this.

RecommendationsListen: “This Is (Not) Beethoven,” an album of Beethoven works delightfully recomposed by Arash Safaian.

Read: Babel by R.F. Kuang. It’s dark and makes you think—my favorite kind of book.

Watch: Arrival by Denis Villeneuve. A masterclass in blending high-concept sci-fi with emotionally compelling character work.

A housekeeping noteTo help prevent the newsletter from going to your Spam folder, please move this email to your Primary inbox. If you can’t find the newsletter, check your Spam folder or Promotions tab.

If you’d like to help improve this newsletter, please take a few minutes to answer this brief Reader Survey.

Thanks for reading.

– Grayson

January 10, 2025

Memento mori, memento creare.

How often do you think about death?

I think about it often. The end of things. The ephemerality of life. My own mortality.

That may sound dark. But facing that darkness, facing the fact that your life will inevitably come to an end one day, is one of the most important practices we can have. Especially as writers.

The Ancient Romans had a phrase for this: memento mori. Just two words, but they held a deeper power.

Memento mori means remember death. Remember you must die. It was whispered into the ears of great leaders as they rode in triumphal parades through Rome. At the apotheosis of their careers, these two words would serve as a reminder. This moment will pass. For all the glory you gain, you can never escape the grave. All must perish.

Awareness of our own mortality puts everything in perspective. It illuminates what matters, and what doesn’t.