Tori Paquette's Blog

March 16, 2021

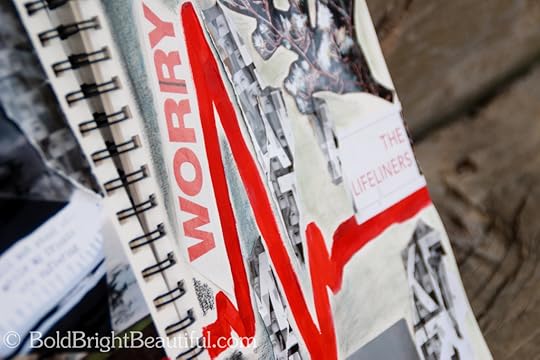

What Might Have Been the Hardest Year of Our Lives

This year has been the hardest of my life.

This year has been the hardest of my life.

I keep wanting to say this, and yet even as I think it, I hesitate. I can think of other seasons of life which felt impossibly hard and painful: in high school, when my existence was a revolving door of panic attacks and sleepless nights and a depression that felt inescapable; as a kid, when I lay in bed at night terrified because I thought there were demons in my room and I had to muster up enough faith to pray them away. Or in college when I dove into a charismatic Christian culture full of spiritual fervor and evangelical zeal, a zeal that made me feel I was never good enough and washed up all my old traumas and anxieties until I felt physically ill.

Yet I can’t quite compare these types of difficulty and pain, because is pain ever something that can be compared? I remind myself of this, too, because I feel guilty knowing that while this year has been hard for me, it has been hard for all of us—and so much harder for some, for those who have lost jobs and homes and loved ones. This year is painful in a particular sort of way, a way that we all share and yet is unique to our own situations, depending on where we were when the pandemic interrupted our story.

When the pandemic interrupted my story, I was in the spring of my senior year of college, the year when my belief system as I knew it fell apart. The previous semester I had realized that I might not be an evangelical anymore, but I wasn’t quite willing to admit it to myself yet; the costs were too high. I thought it meant losing my friends, my family, my church, my plan for my life, my identity, possibly even my salvation.

Yet it felt like something that was happening to me rather than something I was deciding: the beliefs I once held unraveled, all of them, and there was no putting them back together. I had unwittingly entered a metamorphosis I couldn’t return from.

I was right that the cost would be high. Suddenly I found that I couldn’t attend my charismatic church without being shaky or angry or deeply disturbed; I couldn’t share all of my thoughts and struggles with my friends without hurting their feelings; I didn’t quite know how to talk to my family anymore, and they didn’t quite know how to talk to me, either.

Suddenly I felt deeply alone in a way that I never had before: the community that I’d been promised was mine, the people who had held me together for years, the ones with whom it was us against the world—suddenly I didn’t belong. I knew it, and they knew it, and none of us quite knew what to do about it. There weren’t really big angry arguments or heart-stopping conflicts, just a lot of confusion, of talking around issues, of discomfort and uncertainty.

While my friends went to church together, I drove alone to an Episcopal church down the road, sat in the back by myself, read the liturgy and sang hymns I didn’t know and tried to find Jesus in a new place, far away from the pain and confusion. I was surprised, almost, to find him there—different than the Jesus I knew, but there, quiet and gentle and not at all afraid of the tiny faith I was holding in my hands, which to me looked like a completely shattered life.

This is where I was when the pandemic interrupted me almost exactly a year ago: Shattered. Just barely starting to put the pieces back together in a way that made sense. Holding on to the small but growing community of mentors I’d pieced together, mostly professors and clergy who listened to me as I tried to discern who I was now that everything had changed. And then, like every other college student in the United States, I got sent home, with about three days to pack up my belongings and say goodbye to my friends and my college and the life I had built for myself there.

At my parents’ house, I felt like I was walking around in a haze of grief. Our world had been upended in every way. None of us knew what was going to happen; we didn’t know if we should wear masks or not; grocery stores felt apocalyptic; we thought it might be better in a few weeks. We were wrong. Every week I drove twenty minutes over the border of New Hampshire, parked outside a Dunkin Donuts, and used their Wi-Fi to call my therapist who was only licensed to practice in Maine. And then I would drive home, teary and exhausted, often too afraid of contact with COVID and too anxious about human interaction to go through the drive-through and buy a donut.

I loved my parents, and my parents loved me, and yet living at home together was hard. Like any college senior, I had been living on my own for a while and it was strange to be a dependent again. I was still navigating the pain and confusion of my own journey, and I knew they were hurt, too, by the choices I made, choices that probably felt like a rejection of them as parents and of their foundational beliefs. I wanted to fix it, but everything was still too close, too tender. Our world had become so small and pressurized, limited to the four walls of our home, a cocoon in which we were all breaking down in new and uncomfortable ways.

My friends from my work in Jewish programming in Maine invited me to come live with them, so I packed my bags and drove back up I-95, two and a half hours north of home, and moved into a recently emptied room in my friend Sarah’s apartment. When I first arrived, all it contained was a handful of plants and a mattress on the floor: a makeshift, temporary home, but a space to make my own all the same.

I will never, ever be able to express my gratitude for what Sarah and the local rabbi’s family did for me over the course of the four months I lived with them. Every evening Sarah and I walked just under a mile to the rabbi’s house, and the six of us—the rabbi and her wife, their two small daughters, Sarah, and I—sat around the table and ate together. Nearly every day for four months, I had a homecooked meal at that table, and there was never any expectation of me giving back anything in return.

When my car was declared “unsafe to drive” and far too expensive to fix, when I got the email from my graduate program at Princeton Theological Seminary that there would be no in-person classes and I should consider finding another place to live, they were the people I cried to. They were the people who helped me develop new plans. I was supported, too, by other clergy and professors I knew who were still in the area and who spent hours sitting with me outside, six feet apart, listening to me process a story about my life that I still didn’t fully understand.

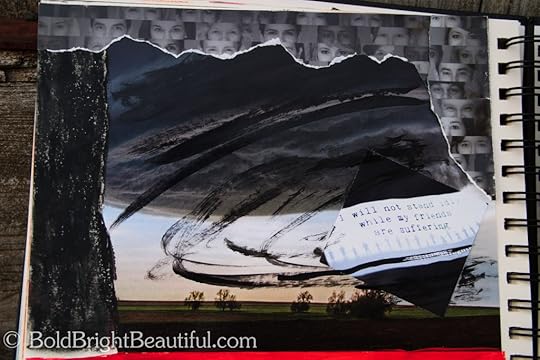

Yet all of this support didn’t change the fact that I was grieving—and I was angry. I was furious, actually. I felt the kind of rage that I didn’t know could exist embedded under my skin, taking deep root in my body—a body that I had always thought was fully compassionate and tender and gentle. I was furious at the world, at the president, at the conspiracy theorists who’d coopted the Christianity I once loved, at the people I still loved who seemed to be ignoring the many ongoing injustices brought to light by the pandemic. I was furious, and I was terrified about the future, which made me more furious, and all I wanted to do was escape. I wanted to escape everything that was closing in around me: the narrow walls of the apartment, the confines of pandemic life, my own skin trapping me inside with all the rage and the deep sense of homelessness and all the things that felt shattered and not-yet-healing. So I ran.

When I think of this past summer, what I think of—aside from the kind of love and support that I can never pay back—is the running. I think of putting on my pink Adidas shorts and my old staff shirt from the Maine Conference for Jewish Life and running—out of the rickety apartment building, along the cracked pavement of low-income neighborhoods, past the Catholic graveyard, past the local ice cream joint and the mini golf course, and back down my own road. Well, Sarah’s road. And then I’d trod back up the narrow, grey carpeted steps, back up to the sweaty third floor.

As loved and supported as I was, it was really hard. I felt displaced; I felt like I couldn’t go home because I knew my family and community weren’t taking the kinds of COVID precautions I was comfortable with. As a person whose obsessive-compulsive disorder had trapped me for years in a spiral of fear that I might accidentally pass on a deadly disease to someone I loved—a fear that I had only overcome by telling myself it was completely unrealistic—the pandemic felt like one of my worst nightmares come to life. This time, the risks were very real, and protecting myself and others felt far too important for me to compromise on.

I decided to move to Princeton despite classes being fully online. It seemed like the best of the options I had. I drove nine hours alone with all of my belongings packed very tightly into my newly acquired (used) car; I arrived sweaty and shaky and carried my boxes into the student apartment where I would be living alone for the first time in my life. That first night, all I had energy to do was make my bed, eat a PB&J, and send texts to my family and mentors telling them I’d made it. I sent one extra to a couple of dear clergy friends that essentially said, I’ll probably feel better in the morning, but right now I feel like I’ve made a huge mistake. The space felt huge and empty, and I felt trapped in a new place where I knew virtually no one.

Yet I started to put together a life: I slowly acquired furniture and dishes and the basic necessities to make a place feel like one’s own; I made a few friends through group chats and picnics. It was hard at first to be in a Christian environment again, especially one where people prayed out loud at the start of classes and asked us to share our religious backgrounds. It was a story that still felt far too vulnerable to share in a sea of classmates I didn’t know and might not meet in person for months. But soon I realized that here, I was not the only one with my story, and I might just be able find a home in this place with these people.

Then I ended up, rather unexpectedly, in a relationship with someone who was really good to me. He was supportive, he listened, he held me when I cried. For a little brief snippet of 2020, I had a bit of relief, a part of my life that was solely happy and good; I had a space—a person—that felt like home. He traveled with me to my brother’s wedding because I was anxious about the drive and navigating family relationships in a pandemic context; he brought me home with him for the holidays when I still felt I couldn’t go home because of COVID. We got really close, and it turned out I loved him.

When it ended, I cried for weeks. And this is where I come up against that phrase: hardest months of my life. Because wasn’t it just a breakup, after all, and in fact a relatively brief relationship in the grand scheme of things? Haven’t I been through worse—including years of mental illness and religious baggage I’m still unpacking?

Yet it wasn’t just a breakup: it was yet another loss after a year of losses. Yet again I was faced with the terrifying feeling that I didn’t have a home in the world; yet again I lost my sense of stability and security and belonging. Yet again I was trapped in the four walls of my apartment with no escape from the overwhelming grief and a future that felt suddenly stark. I felt fragile and alone, so far from the places I used to belong and the things I used to hold certain, and so far from ever finding them again. Every day I am reliving these losses; alone in my apartment, they feel inescapable.

I think what I am really trying to say is this: the kind of hurt and pain I am feeling is so deep and pervasive that I can’t put it into words. Because how could we put the losses of this last year into words?

I know, even as I say this, that ahead of me in my life lie far deeper hurts and pains, things that I can’t yet imagine surviving. But this is the one I am surviving now.

Some days I am hopeful that things may be starting to get better, that I may be through the worst of it already. Some days I think things will never get better: that perhaps the pandemic will never completely end and our worlds will remain small and isolated, that my life will always feel this unstable and alone.

And yet I know that I am not the same person I was a year ago. This whole year I was becoming, holed up in the cocoon necessitated by pandemic life. I am still becoming, and I am not sure exactly who I will be on the other side of this, but I certainly know more about what that girl looks like than I did a year ago.

I know now that she can and will find a place in mainline Christianity, that she doesn’t have to leave her God behind to be herself. I know that she is vegetarian (mostly) and a cat mom (still not sure which one of these is more surprising), that she loves to run and to cook (also surprising). I know that she’s funnier than she thought she was, even if her humor is cynical and dark. I know she likes to wear button-ups tucked in and Birkenstocks with thick socks because they make her feel confident and quirky and a little like a Mainer.

I know that she has real and true friends in Princeton whose interests and eccentricities bring out the best in one another, and who will show up for her, not just right after the shit hits the fan, but for the days and weeks of painful processing afterwards. I know that when she loses a person she loves and it feels like her carefully constructed and still-fragile world has fallen apart for the hundredth time, she will witness the presence of God in the darkness every day, every moment, and it will be the most certain thing in her world, despite all that her faith has been through.

I know she is strong and resilient and capable of handling a lot more than she thought she could: moving alone and living alone, managing all the cooking and the cleaning and the paying of bills, buying and selling cars, coming up with handy solutions to practical problems, filing her taxes, handling a bad breakup with courage and dignity, consistently responding with mercy and care when she has been hurt, setting the firm boundaries necessary to protect and prioritize herself and to allow healthy relationships to thrive.

I know she will be okay. And I know that not because I feel like it most days, but because I know who she is. I know she will ask for help when she needs it. I know she is surrounded by people who love and support her. I know because she and her parents have figured out how to talk honestly again, and they have been a lifeline in her grief. I know because she has been creating her own bright future for years and she has so many good opportunities lined up in front of her: chaplaincy training this summer, a community organizing placement this fall, and her new church helping her through membership and then the Presbyterian ordination process.

I know she will be okay because she loves who she is and what she does, and so eventually she will start loving her life again, too. It might take antidepressants to get there and to remember that her life is worth living, but that’s okay. There’s no shame in that.

I am still becoming the person I want to be, and it is really hard, and it has cost me a lot. But eventually this cocoon will crack. Eventually the world will open up again and I will be able to breathe in deep and say: Oh. This is why it was worth sticking around.

I believe this for you too, wherever the pandemic interrupted your life a year ago, wherever you are now. Eventually our cocoons will crack and this painful, cramped place we’ve been in will expand and we will finally be able to breathe. We will finally be able to breathe.

And perhaps when we’ve emerged from these cocoons, we’ll find that we’ve become in ways we never imagined a year ago, that we have discovered we are far stronger and more capable and more resilient than we ever thought we could be.

May 5, 2020

Why I Am Not An Evangelical Anymore

At some point we all have to answer the question, “Who am I?” Who am I, apart from who I have been told I am supposed to be by my family, my friends, and my community? And then we have to come to grips with the fact that some people won’t be pleased with our answer.

In the last year my answer to that question has changed dramatically, and it has changed in ways that I know have been uncomfortable and even painful for those around me. It has been uncomfortable and painful for me too.

This year I left evangelicalism, and I know I’ve left for good.  The funny thing about leaving evangelicalism is that many of your fellow evangelicals aren’t quite sure what it means when you say, “I’m not an evangelical anymore.” Evangelical isn’t a term we use in our day-to-day conversation, and I’m not sure I even understood it until I was leaving it. I think this is because we just call ourselves “Christians,” or “born-again Christians,” and we all know what we mean when we say this. We mean Christians who are like us, Christians who believe the Bible is the authoritative source for how to live our lives, who have what we consider an “active” relationship with Jesus, and are heavily invested in sharing our faith with others.

The funny thing about leaving evangelicalism is that many of your fellow evangelicals aren’t quite sure what it means when you say, “I’m not an evangelical anymore.” Evangelical isn’t a term we use in our day-to-day conversation, and I’m not sure I even understood it until I was leaving it. I think this is because we just call ourselves “Christians,” or “born-again Christians,” and we all know what we mean when we say this. We mean Christians who are like us, Christians who believe the Bible is the authoritative source for how to live our lives, who have what we consider an “active” relationship with Jesus, and are heavily invested in sharing our faith with others.

We can recognize these Christians by the way they talk about their neighbors (as people they’re hoping to tell about the Gospel), the Bible (should be read daily and to answer any questions), and God (as our father and best friend who we talk to regularly). I don’t say this to mock. These Christians are so good at building community and constructing a narrative for a meaningful, purpose-driven life. Often they are incredibly generous to their communities and friends, genuinely yearning to see the best for those around them–whether that means providing them with a place to stay when they need it, directing them to the Scripture that best addresses their problem, or telling them about a Jesus who can save them both from a life of emptiness and eternal separation from God.

This isn’t always the case, of course–there are plenty of churches that are hypocritical, shallow, and internally-focused rather than focused on serving their communities. There are plenty of Christians who are self-righteous and manipulative and even abusive. And while I have witnessed that, I have also witnessed the good side of this kind of Christianity. I have been loved well by my college ministries and by many evangelicals in my life, from homeschool moms to church friends to roommates and family. This is the community that supported and championed me as I went off on missions trips and on academic programs. They prayed over me when I felt anxious and alone and walked with me through heartache. They have, in countless ways, shaped me into who I am today.

But who I am is not, and can no longer be, an evangelical.

This is becoming a pretty frequent cry these days, particularly among the younger generation. Many of us are tired of hypocrisy, especially when it comes to politics. We don’t understand how it was white evangelicals who elected a blatantly immoral and arrogantly uninformed president. We don’t understand how our churches are not crying for justice for immigrants, refugees, and victims of gun violence. We don’t understand how the church can turn its back on the earth God gave us to steward well. We don’t understand how the community that raised us can continue to ignore and even deny science, racism, economic inequality, sexism, homophobia, the wisdom of academic institutions and experts, and the sea of ongoing injustices and inequalities in our society.

Yet while I understand this frustration and echo it, this is not the main reason I left evangelicalism. I don’t believe evangelicalism in its essence has much to do with conservative politics; they have simply been bound together through a complex and unique history, particularly in the United States.

No, I left evangelicalism for theological reasons. I left evangelicalism because I no longer believed the central theological tenets, which are as follows:

The Bible is the authoritative, inerrant Word of God.

One must be “saved”–that is, choose to believe that Jesus is the son of God and their Savior, a choice often accompanied by dramatic life change–to avoid eternal punishment and to live a fulfilling life.

Christians, thus, must try to get other people to believe in Jesus so they can be saved too.

In evangelical Christianity, this is considered good news–in fact, that’s what the word “Gospel” means: good news. It is good news that God gave us a book in which we can find the answers to our questions and hear his voice. It is good news that he sent his son Jesus to a gruesome death, in order to save us from our depravity and the despair of hell. It is this good news that we must share with others: You are inherently wicked and thus must be saved from hell; I have a God who endured your punishment on your behalf, and all you have to do is believe He did it.

There are ways to phrase this that feel more palatable as good news. Perhaps hell isn’t a fiery place of eternal torture, but simply a place where God is not present, or a state of nonexistence. When faced with any of those options, an eternal life of bliss in heaven certainly would be good news.

But many problems remain: Why would a good God take out his anger about sin on his son in such a brutal way? Do I really believe my friends and neighbors who don’t believe in Jesus deserve such a brutal death or eternal torture? What about the many ways the Bible doesn’t line up with history or science, or the many texts within it that contradict each other?

Evangelicals have an entire system of answering these questions, called apologetics: the defense of the Christian (read: evangelical) faith. These answers are aimed at explaining away the tricky questions that pull at our conscience–questions about our friends going to hell or other unjust suffering–by finding ways to justify it, to explain how those tragedies really are just according to God, despite how unjust they feel to us. We especially have to defend the Bible’s authority and accuracy because if we can’t trust that, the faith we have built on all our careful, systematic answers and biblical interpretations falls apart.

I took apologetics as a course in high school, asked the questions with many Christian friends and leaders, answered the questions for my non-believing friends, and became an evangelical leader myself–in college ministries and on missions trips and in Bible studies I hosted in my dorm room. I was absolutely committed to my evangelistic goals and my faith, doing everything I could to bolster it: leading and attending Bible studies, prayer meetings, worship nights, church services, and my own quiet times with the Lord.

But even though I knew I could frame the Gospel in a way that seemed to avoid or cover up the uncomfortable parts (and, when asked, could simply say, “God is too big and mysterious for us to understand” or “God’s ways are higher than our ways”), the questions were still there, growing bigger and bigger all the time.

To me, it seemed grossly unjust that anyone who didn’t believe Jesus was the son of God would be punished eternally for it. There could be any number of reasons not to believe in Jesus, including: having never heard about him, having only seen him poorly represented in the church, growing up in a different religion, and having intellectual disagreements with the Christian faith (which I secretly shared).

And as much as I could quibble about what “eternal punishment” meant, ultimately it all came down to one dividing line: Did you believe Jesus was the son of God, the Lord and Savior of your life, and the Messiah of the world–or not?

If you did, you were “in”; if you weren’t, you were “out,” and it was our responsibility to do everything we could to get you in. Which turned out to be a real inhibitor to interfaith conversations, as I discovered when I joined the Jewish Studies program at my college, ended up working in state-wide Jewish programming, and ultimately lived in Israel for five months. It also came with deep ethical issues, especially in the Jewish community: was it right to try to evangelize someone who was actively involved in another faith? What if they seemed deeply satisfied in their faith, despite the fact that I was told only Christians could be really, truly satisfied? What about the longstanding history of Christian persecution of Jews, leading to some very legitimate distrust today?

I knew all the right arguments to justify my beliefs and actions, but it didn’t sit right with my soul anymore. And after three and a half years of college and religious studies, I could no longer read the Bible as I had before. I could no longer turn my back on scientific consensus on evolution and climate change, on archaeological evidence that contradicted biblical records, on the work of historical-critical biblical scholars who had good evidence that these texts were often written hundreds of years after the events described, and usually for contemporary political agendas rather than to give me, a 21st-century reader, a solid understanding of history and science and how to navigate today’s questions of gender roles and my own anxiety about the future.

Most of all, I could no longer turn my back on the texts themselves: texts that often offered multiple theological viewpoints on the same issue, were opaque rather than clear, and did not contain the straightforward messages I had always been told they had, messages about salvation, the afterlife, the end times, and the purpose of my faith overall. It seemed the Bible–the Gospels and the Prophets in particular–were much more about justice for the oppressed and real-life change on this earth, here and now, than I’d ever realized, and had very little (if anything) to do with staying out of hell. That, to me, seemed a far better “good news” than the one I’d been given.

Yet as the reasons to leave piled higher and higher, I was terrified. Would I lose my community? What answers would help me navigate the world? Could I still be a Christian? Was I going down a wrong path headed away from God, or even for eternal damnation? I knew that was what my friends and family must be thinking, and yet I couldn’t stop.

I knew if I continued to believe what I had always believed, I would not only be denying the intellectual, ethical, political, and biblical evidence in front of me, but also the voice inside me that told me what was right. My conscience, my soul, cried out that it was wrong to separate people into these categories, it was wrong to go into relationships with the agenda of conversion, it was wrong to defend a God who sent good and loving people to hell for not believing what I believed.

I had been told that my heart and emotions were deceitful and I ought to hold onto my evangelical faith above all things; that the Bible was higher than human intellect. But it turns out, to keep living like that would have been to live in opposition to the things I actually believe, to my intellect, and to my experience of who God is. So I left.

I know, for many, this won’t be a good enough reason. I know there are lots of answers and explanations and alternative frameworks for many of the issues I have just raised. But for me, this is no longer a question of whether there is a good enough answer to justify the things I was raised to believe. I do not believe them anymore. I cannot.

This has put a great strain on my relationships with family and friends, and has meant the loss of some communities that were important to me. Even though those are communities full of kind, loving people, I know I could not go back and be fully honest about what I believe now. I would be an outsider, someone who went down the wrong path and abandoned the truth. I would threaten people’s core beliefs and make them feel rejected and betrayed. I would not be welcomed into positions of leadership. I would not count as a “Christian.”

And yet I think there is a way forward for me in Christianity still. This Christianity is much less clear, and I have few certain answers. Yet for the first time I do not have to shut out my mind and my heart to believe the “right” thing. I can wrestle with the Bible, understanding it in its context, listening to the many and varied voices, agreeing with some and challenging others. I can bring my experience of God and not just the God of the Bible to the table, a wide-open table surrounded by people of different religions, nationalities, and sexual orientations, all doing our best to understand who God is and who we are. I can fully engage my love for scholarship and embrace my sense of justice and desire for inclusivity, even–and especially–in shaping my theology.

The many and varied texts that make up the Bible compel me; biblical scholarship has opened them up for me in new, surprising ways that give me hope for my faith and the future. As my old methods of biblical interpretation have fallen away, I have found that God is not who I thought he was: he is far better.

I am still not sure exactly what I believe, but I will continue to write about these things because they matter. Our religious communities matter; they give us connection and purpose and family; they help us become better people and serve our world. Our beliefs should make us better neighbors, better citizens, better friends.

I still believe in a world that is better than this one. I believe that humans are meant for more than this, that we have a deeper value than our biological existence alone can explain. I still believe in forever.

And I want with everything that is in me to believe in a God of justice, a God who promises to make things right, a God who is not interested in vindictive punishment, but in overturning systems of injustice and oppression and restoring every suffering person–and this entire, beautiful earth we live on–to wholeness.

If there is a Christianity I believe in, it is that one.

—

Postscript:

To everyone who ever felt that I was trying to change them, to make them a Christian, or was doing anything less than fully loving and accepting them as they were: I am so deeply sorry. I have no real answers for you anymore, but I realize now that’s probably not what you were looking for anyway.

To everyone who perhaps feels, as I described, hurt or threatened or rejected in reading this: I’m sorry. I know this is hard stuff. I hate that me leaving also makes people feel left behind. Please know that my intention is not to convince you that you’re wrong, but simply to say that I left and give a reasonable explanation for doing so. I hope doing this will help me to live a little more honestly in the world.

To anyone who maybe feels a little bit of hope that they aren’t alone and that there are more answers than the ones you’ve been given: I believe in this for you. You can have it too. It will be a long, hard journey, but it is so worth it to be fully and finally honest with yourself, and to, maybe, discover a faith that actually feels like good news.

July 22, 2017

A Letter to the Anxious Christian

Dear friend,

When you first told me you thought you had OCD too, I didn’t believe you. Every other person thinks they have OCD when they first hear of it, because they like things neat and tidy and clean. Over and over I find myself explaining that OCD is not just about those things, not even mainly about those things.

But then you began to tell me about all the religious anxiety you’ve spent your life dealing with, the panicky need to pray or speak for the Lord, or else.

Or else something bad is going to happen. Or else that person will never be saved. Or else that person will die.

And even though it makes no logical sense, that A could lead to B, the fear of the possibility is too great for you to ignore. So you pray and speak and do, driven by terror of what could be, and how you would be the one at fault.

In this way, faith becomes a torment to you. It is this huge weight riding on your shoulders, that you must be the one to save the world. And if you turn your back on this burden, turn your back on faith altogether, you too will lose the only hope of eternity you have.

On the outside, it looks like your faith is strong. You are praying, speaking into lives, seeking God with everything you have. But inside you are a wreck. You are consumed by fear, scared of God, yet scared to leave him. You are controlled by this, enslaved by it. When you try to speak about the weight on your shoulders, people encourage you to have more faith. So you drive harder and the fear digs deeper.

I am speaking from my own experience, of course; this torment fits each of us differently, according to what beliefs we hold, what we fear most. But I know the weight of it. And I am amazed, truly, at the strength with which you have held to your faith, the tenacity with which you pursue the Lord, that you have spent all these years loving and serving him despite the days where it feels like torture. I do not know how you pushed forward for so long.

Friend… I want you to know that there is a life where this weight is lighter. Where you are not controlled by fear. Where you can call these compulsions that drive you to religious action for what they are, and learn how to serve the Lord for the right reasons, with a heart of peace.

The first step is calling OCD what it is. These fears that play on repeat in your mind, these torturous thoughts you can’t get rid of? They are obsessions. They are a disorder, a chemical problem in your brain. They are not your fault. The actions that you must complete in order to get rid of the thoughts or keep bad things from happening? They are compulsions, and they only reinforce the obsessions. It is like feeding a monster: it will stop growling as long as its stomach is full, but the more you feed it, the bigger it grows.

Each time you follow through on a compulsion, you are saying you believe the obsession, that the obsession is true: It is true that your friend will die if you don’t pray for them. It is true that the stranger will never know Jesus if you don’t speak to them. It is true that you won’t go to heaven if you don’t repent for every tiny sin you might have committed today.

Hear me on this: those things are not true.

Yes, we use this kind of language in the church to encourage people to step out of their comfort zones and follow where the Lord is leading. There are times where it is important to step out, and there are people who God speaks to in this way.

But you are not one of them. God knows exactly how your brain works. He knows that speaking to you in this way will cause you torment and enslave you to fear. And he doesn’t want that for you: because his Spirit is not one of fear, but of power, love, and sound mind, and because where the Spirit is, there is freedom (2 Timothy 1:7, 2 Corinthians 3:17).

If it’s making you a slave to doing something, it’s not from God.

Because guess what? God doesn’t need you. He’s not relying solely on you to save the person across the street. He’s not dependent on you to give a message to your friend or to intercede for global issues. God can accomplish his purposes without you.

He doesn’t need you, but he wants you.

God, You don’t need me, but somehow You want me/Oh, how You love me, somehow that frees me

He wants you to be a part of what he is doing in this world. He wants you to work with him, to walk alongside him.

But most of all he wants you to know his love and love him back.

Knowing that love looked a lot different for me than it did for most Christians. It meant not praying when I had an obsessive urge. It meant not worrying about the occasional curse word. It meant not focusing on messages of repentance and poring over every sin I may or may not have committed. It meant not striving to get nearer to God. It meant not going to church for a while. It meant not engaging in spiritual warfare. And in this process of stopping my destructive behaviors and figuring out what my faith looks like, I have not gotten it all perfect. But it was so much better than continuing down the path of destruction and fear and slavery that I was on.

And through it all, God still loves me. I know that love better now because I know God is not the one putting the burden on me. The burden came from a chemical disorder, and that disorder lost its grip on me as soon as I stopped trying to fight demons and got an antidepressant prescription instead.

I know now that God wants me to live an abundant life, a life of wholeness and freedom. He wants me to live for him because I am loved, not because I am afraid. He never tormented me with religious ultimatums and compulsions, but instead wants me to be free from them. I can actually love a God like that.

I am still learning what that relationship looks like, how it can be healthy instead of harmful for me. The good news is that God isn’t in as much of a rush as I am. He has all of eternity to woo me to himself. He doesn’t need me to be perfect right now in order to love me or to work through me. He will work on one thing at a time, as I’m ready, as my mind and my heart can handle it.

Friend, if he loves you and wants you to have a whole, full, and abundant life, then it’s okay to pursue that wholeness: to learn deep breathing, muscle relaxation, and grounding techniques. To speak to a doctor or a counselor. To take a little pill every day until, one day, you can see the goodness of God and the full life he wants you to have.

It is a lifelong process. You are not searching for a single key: a method of prayer, a theological idea, a demon to get rid of. You are choosing every day to stop striving to fix what is wrong inside you, to stop trying to make yourself right with God. You already are right with God because of Jesus.

And in this place of stopping, of not trying to do it on your own, of not being driven by fear: you will begin to see a God of blessing, not of torment, a God who desires wholeness and restoration in your life. A God who simply wants you.

May 29, 2017

what antidepressants changed in me, and why I stopped taking them anyway

The medication has run its course through my body and is fully washed out, now. Now I am empty; now I am doing this on my own.

People keep asking me why I chose to go off antidepressants. I was doing well, I was stable, and there were no side effects. Talk about a miracle drug. I could be happy and as close to carefree as I’d ever been, and it cost me nothing.

But maybe you can understand? These blogs, they’re not unlike my journals. They’re full of anguish, frustration, hope. And yet as I looked back at what I wrote even a year ago, I saw intense emotional upheaval over events and situations that didn’t merit it, things that felt almost childish.

I thought, maybe, I’d grown up since then.

So this is what I told people who asked about my decision with genuine concern: I feel more stable now than I ever have before. I had begun to look at the pill in my palm each night and wonder why I was taking it. I had never intended to be on the medication forever.

Did I feel shame about taking it? Not really, not anymore. I had felt shame at the beginning when my grandmother passed away, and I felt as though I was trying to be happy when I should have been grieving for her. But now I know that there is no shame in getting help, in realizing when I can’t do it on my own.

But now I believe I can. I believe I can do it on my own, and not because of trying harder or having more faith. Instead, this time of medical support has taught me through experience to see redemption and goodness instead of despair. It has shown me that life is not as bleak as I once thought, that my mind is not a prison, that there are good things within reach and this is not the end. It has distinguished between the real me and the sick me: the one who believes her friends talk about her behind her back as a burden and wish she weren’t around, the one who can do nothing but sit and cry, the one whose every word is a plea for attention and affirmation.

I know now that I am not that girl. I was finally able to explain to my friends the other person that I am sometimes, to tell them what she needs and feels, to ask them for their help. Just sit with her and listen; nothing you can say will make it better. Talk about something else at first; she can’t get the roiling, bitter words out of her head just yet. It takes time, and she believes you don’t want to be there; she will keep saying sorry, sorry, sorry. Offer to pray for her.

The praying helps. It is calm and quiet and hushed, words outside of my own head that ground me, that prove to me the world is not all in turmoil. Music, too, is a near-instant tranquilizer for me—hymns and acoustics, reminders of God’s goodness. If I quiet my body and breathe and listen… just let the music take the place of my surging thoughts… everything becomes okay again. My muscles slacken. My eyelids sink. My breathing evens. I find that there is something stable and real outside of my inner turmoil, that the panic won’t last, that I have not lost control over my mind and myself.

Music that grounds me.

The medication taught me these things and for that I am grateful. I am grateful because I know myself now, and I know I am not the desperate, hopeless, needy girl that takes over sometimes.

Instead, I am someone who is funny, who is kind, who wants to believe the best of others and to love them without trying to change them. I am sarcastic and loud and silly, and I am at home in stillness. I am honest to a fault. I care about people first, more than work or academics. Of course I am imperfect, always making mistakes, saying things wrong or saying the wrong things. But I am no longer defined by the voice in my head that tells me I am the wrong things.

The bad days are few and only come when my world is upset. An argument, an insult. There have been anxiety attacks and tears and phone calls to my mother. These things would have happened even if I was on medication, just maybe at a lower decibel. The difference now is that I know I will get through them, that this is not me, and that the people around me know who I really am and are ready and willing to help me get back to her.

And the other difference? I have finished my first year of college and I have changed.

Since I got home, I have thrown out and donated bags upon bags of my things. I have gotten rid of papers and bank statements and airplane tickets and music sheets dating back to elementary school—things that I will never use again, but had never been able to get rid of before.

But I never could. I held onto everything because I was afraid. Afraid of change, afraid of scarcity, afraid of betraying something that held memories for me or giving up something that I’d spent good money on. And I didn’t know myself well enough to know what was really me and what things just didn’t fit into my life or my personality anymore.

And if now, suddenly, I am able to move on, throw out, say goodbye—then I know I have changed.

Or like this—I used to agonize for weeks over cutting my hair. Should I cut it or not? How short? I’d cry over it, let it consume me.

This time, I got home, set up a hair appointment, and chopped off several inches with hardly a thought. And for the first time ever, I wasn’t near an emotional breakdown in the stylist’s chair, and I didn’t need my mom to come with me to the appointment. I do not return to the mirror again and again, questioning my decision; I simply smooth the curls and feel free.

I have the sinking sense that these are steps I should have made a long time ago, steps that came much earlier in life for everyone else. I feel ashamed that I was a child in so many ways for so long.

And yet I am grateful. I am grateful because I made it, finally, to a place I didn’t know I ever could.

– – –

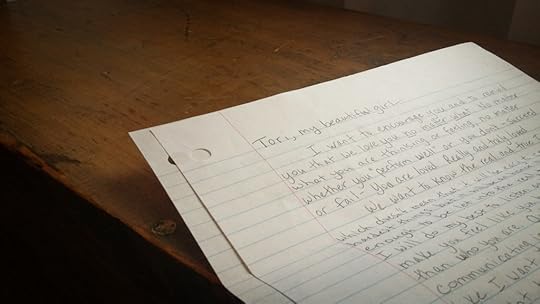

Today I found a letter among the piles of papers, a letter from my mother that she gave to me before I left for Iowa in 2015. It was my first solo trip, and it was at the time in my life when I had just begun to seek help for my depression, when I wasn’t sure I could make it through the two-week camp without breaking down and going home. I imagine my doctor had pulled my mother aside less than a month before and told her I had considered self-harm. I imagine it because he must have—he was required to by law—but she never said anything. She only continued to love and support me, to tell me that she wanted to know what I was feeling even if it hurt her.

The girl she wrote the letter to is someone I’ve almost forgotten. A girl who was scared to leave home, scared to disappoint everyone if she failed. A girl who needed to be reminded of all the people who supported her, who needed to be reminded that they supported her because they loved her. It was not about success or failure, but about an opportunity, a chance to go be brave and do what she loved and hopefully find herself in the process.

I see now that going to Iowa was not just about going to writing camp and becoming a better writer. It was also about leaving home, flying across the country, doing something I wasn’t sure I could do alone, proving to myself that I could do this even in the face of my mental illness.

The girl who received that letter didn’t know if she could. The girl I am today knows she can, and is now doing the very things she once felt powerless against: cutting her hair and cleaning her room, living away from her family, traveling, going off the medication, talking openly about her anxiety, saying with confidence: that other girl is not me. Not today.

– – –

Want to read my recent guest posts? Here are a few:

When You Feel Abandoned by God on Delight & Be

There is a reason why I don’t talk about God very much when I talk about mental illness. I think it’s because I’ve felt its sting myself. On hard days—days where panic rose in surges like a loose wire inside my chest, where I felt as though something inside my head had caved in and all the lights had gone out—I would try to express this struggle, try to ask for help. … [read more]

It’s Time to Be Set Free from Shame on Delight & Be

Dear friend,

You do not have to hide. I see you there, hiding yourself, hiding from the people around you, hiding from God. And I know what it’s like to hide. I lived in hiding for a long time. See, I hid for the same reason that Adam and Eve did in the garden: I felt ashamed. … [read more]

When You Don’t Feel Qualified on Delight & Be

Sometimes I feel I’ve lost my voice. Sometimes I feel like I have nothing to say, no encouragement to give—like I’m in a stuck place and can’t free myself, let alone help someone else find their way. And I wonder why God has called me to this: to be a writer, encourager, empathizer, counselor. … [read more]

December 29, 2016

The Gospel I Love is not the Gospel We’ve Been Told

I do not know how to tell my story without Jesus in it.

And I think this is what I’ve been running from. I’ve been running from telling my story to people who don’t understand or don’t want to hear it. I’ve been running from the fear that I might offend, be misunderstood, not be taken seriously.

And in the process, I’ve been running from me.

Photo credit: Alexis the Greek Photography

Photo credit: Alexis the Greek PhotographyIf I stop to think too long, I have to evaluate where I fit into this world—this world I don’t fit into. I have to admit that not everyone will approve of me or “get” me. That being myself means being misunderstood.

The only way to change that is to tell my story with all honesty: all the messes, all the despair, all the hope that guided me through. If I do not want to be known as a pretty Christian, I cannot hide my story’s ugliness. If I do not want to represent a neat Christianity, I cannot pretend I have no messes.

I am called to tell the Gospel. And I have shoved this idea aside with all its connotations of preaching shame and fear to win mass conversions.

And yet—this kind of message, this message of shame and fear, is not the Gospel. It never was. It is only what it has become known for, as years and years of oppression have been heaped by the church on the very people Jesus loved so much. And it is in Jesus’ name that we have oppressed!

Even today we oppress, using fear and shame to corner people into looking and behaving like us.

Yet Jesus never oppressed people. Instead of avoiding the sick, he healed them. Instead of accusing the sinners, he invited them to eat with him, live alongside him, and he treated them with kindness and respect. And in so doing, he transformed them.

It wasn’t because he shamed them or scared them into submission. It was because he loved them and wanted the best for them. And they knew that because they knew him. He had invited them out of their old lives into lives of fulfillment, lives where they were known and loved. They were his disciples, his best friends. There were no strings attached. They did not have to shape up or get their lives together to be his friends.

That kind of love is what I want to be known for. A love that breaks down barriers instead of building them up, a love that reaches across group divides and says, I want to know you. Will you tell me your story? A love that makes people feel like they belong, like they matter; a love that empowers them to become their truest and best selves.

This is the Gospel to me. When I hated myself because of a depression I could not lift myself from, the Gospel told me I was loved. When I was afraid because of all the things I could not control, even my own obsessive-compulsive thoughts, it told me I didn’t have to be afraid, that God would take care of me and already knew all of my tomorrows. When I thought about death and time and how meaningless my one small life must be, it told me that my life has purpose, that God has called me to this time and place for a reason, and that death can never end what he has promised me.

When I was ashamed because I had not treated my friends or my time or myself with the respect they deserved, the Gospel told me that I had been forgiven, that Christ had redeemed me and made me new. When I felt rejected by friends and young men, it told me I am accepted just as I am. When I felt alone because I didn’t know who to talk to, it told me that God was always with me, always eager to listen and support.

When I compared myself to others and stared at my body with disgust, the Gospel told me I was beautiful and valuable, and that my soul was always the most important part of me. When I felt broken by grief, it promised that God would restore me and make me whole. When I thought I was too distant and too angry at God for him to love me, it told me that He would always meet me where I was at, that I did not need to behave well or masquerade to earn his attention.

And when I was sad, it gave me hope: hope that tomorrow would be new, that God would not fail me, that he would hold my broken heart and carry me through.

This is what the Gospel is to me. It is hope and love, purpose and belonging, healing and wholeness. I cannot tell my story without this Gospel because it is my foundation. It is the one thing that is unshakable in my life when everything else shakes. It is the story I tell to define myself when all my other identities have failed.

To be sure, there were times when this telling of the Gospel was not enough on its own. There were times when I needed friends and family to come alongside me and give me physical, tangible help—to be fed and clothed, to provide money for educational fees, even to get me medication that controlled my anxiety to a level where I could function. (Functioning, of course, is more than surviving; it is the ability to live at the level I want to live, the ability to keep up with college work without frequent breakdowns, the ability to enjoy going out with friends, the ability to thrive fully in this one life that I have.)

So the Gospel has not made me less human. I would say the opposite: it has made me more human. It has encouraged me to become fully myself. If my personality, my talents, my interests are God-given and God-inspired, then I am called to pursue those things and use them to their fullest potential.

I am called to fully experience this beautiful miracle we call life. I am called to live my story without shame or fear, to live fully, bravely, throwing myself wholeheartedly into pursuing my dreams and loving the people God has placed in my life.

For “He has sent me to bind up the brokenhearted, to proclaim freedom for the captives and release from darkness for the prisoners” (Isaiah 61:1-2), and “to give his people the knowledge of salvation through the forgiveness of their sins, because of the tender mercy of our God, by which the rising sun will come to us from heaven to shine on those living in darkness and in the shadow of death, to guide our feet into the path of peace” (Luke 1:77-79).

I am called to heal, to set free, to forgive, to shine light in darkness, to show the tender mercy of God. The Gospel I tell will not be a message of shame, but of love; not of fear, but peace.

The Gospel is not a story that makes me the hero. In this story, Jesus is the hero—the one who saved me two thousand years ago on that cross, and the one who saves me still every day.

It is not my first impulse to tell this story. In this story, I am broken and struggling and in need of someone to save me. I am someone who has found wholeness and fulfillment in a Gospel that most people don’t understand.

But without this story, my life is incomplete. So this is the story I will tell, the story I will live: the story of the Gospel, of God with us and for us and never giving up on us.

And in this story, this miracle of a life bigger than myself, I become fully me.

– – –

Want more? Wondering where I’ve been? Check out my recent work:

You Are Not Your Pain: A Letter to Myself on TWLOHA, Revival Magazine, and Delight & Be

To the Girl Facing Mental Illness Every Day on Delight & Be

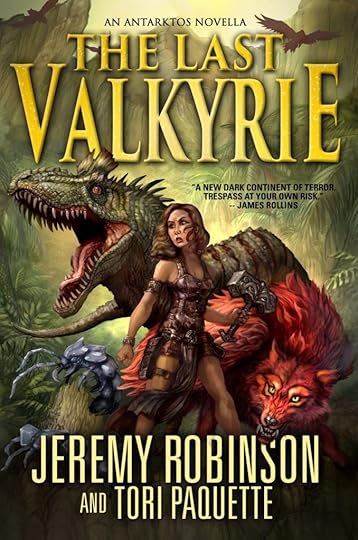

And coming in January 2017 on Amazon and BarnesandNoble.com… The Last Valkyrie by Jeremy Robinson and Tori Paquette (that’s me!), a science fiction novella about the Nephilim, Norse mythology, and overcoming fear. The Last Valkyrie is a spinoff of Robinson’s The Last Hunter series.

Author photo: Jeremy Robinson and Tori Paquette

Author photo: Jeremy Robinson and Tori Paquette

March 14, 2016

Where Mental Health and Jesus Meet

I’m pretty sure that if I wasn’t a Christian, I’d be fully immersed in the mental health awareness movement by now.

I’d be fighting for the rights of people with depression and anxiety, focused on the benefits of medication and psychology, stamping out the stigma.

But as it is… part of me hesitates.

– – –

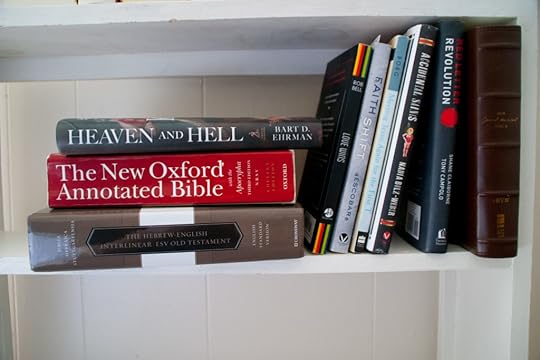

On my twelfth birthday, my dad took me out to breakfast and told me that I have Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. I didn’t tell him this at the time, but I’d already guessed. I’d seen the books on the shelf: Your Anxious Child and What to Do When Your Child Has Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. I’d just been too afraid to ask who they were for.

My dad told me he had the disorder, too. It felt like a big secret had been imparted on me—something I’d never known before, something he never talked about. As far as I could tell, he just went about his life as though it didn’t affect him. I certainly wouldn’t have guessed that he had it. It must have been something he wanted to keep hidden—a shameful weakness.

So I did the same. I kept those three letters tucked deep inside me, my own precious, terrible secret: OCD. I am, I thought, I am OCD.

When I found friends I trusted, I shared it with them in a whisper, terrified to even speak it. They didn’t seem to think much of it. No matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t impress on them the big deal that it was. Many of them said, “Oh, I think I might have that, too.”

No, I tried to correct them, it’s more than just needing to be neat and clean. It’s fear, I wanted to say. It’s irrational fear. It’s worries that I still can’t bring myself to speak out loud—even ten years later.

When I started blogging, I found that I often wrote about the darkness—a vague fear and pain that weighed on my life. It didn’t have a name. I hadn’t put the pieces together. But when the darkness came, the writing came—and with it came the light.

Because of the darkness, I was able to write about Jesus. It resonated with people. I was doing something beautiful—and not only was I helping others heal, but I was healing too.

In my hurt, I could help others heal. In my darkness, I could help others see. It was an incredible and inspiring purpose. It scared me, even. It scared me when I got emails from people who poured out their breaking hearts to me and thanked me for my painful honesty. I didn’t know what to do or say, only to thank them and to keep writing for people like them.

– – –

This June I went to my doctor and I told him how I felt. On the drive there, I kept telling myself that I was overthinking this, that it wasn’t really so bad. But five minutes into the appointment, I broke down in tears.

I remember that he asked me, “When was the last time you were happy?” and I asked him to define what he meant by “happy”.

I started going to therapy. Therapy was uncomfortable. In my head, I knew that it was okay to be broken and hurting and not understand the reason why. But sitting in my therapist’s office, I couldn’t let her in. I couldn’t be broken without trying to explain it away. I had to weight out and rationalize my answers. There was this tremendous pressure to talk and I couldn’t talk. I couldn’t find the words and I couldn’t fall apart.

I tried so hard to be alright, even in my therapist’s office. And back at home or with my friends, I could hardly get the words “my therapist” off my tongue. It felt like shame. Like I was one of the weak ones. Like I was depending on some other person to tell me how to think and feel.

I felt that in the Christian mind, psychology was the enemy. It was looking at the human consciousness without God. It was wishy-washy, perhaps even Zen-like. It was all based on drugs and guesswork and, most of all, lack of faith.

I still get scared when I say the word “depression.” I feel that all heads in the room will turn and say, “You don’t believe in God enough.” I wish those people could know I’ve already told myself that a million times.

I’ve also held scissors in my hand and wondered if bleeding would make someone pay attention.

– – –

I started the medication in January a week before my grandmother passed. (Time is before and after now; we measure the weeks in relation to her death.)

Even as I sat outside the pharmacy waiting for them to fill the prescription, I told myself I was overthinking it, that I didn’t need help. I’d been through worse episodes of depression and anxiety. Like when I was fourteen and spent all my free time crying, praying, or finding solace in music. Or when I went through a breakup and couldn’t leave the house without shaking and sweating and wanting to vomit.

It had taken me a week to go to the pharmacy. I’d been thinking and wondering and looking at that little slip of paper from the doctor’s office. Generalized Anxiety Disorder, it said. Citalopram Hydrobromide.

How could I resist? It was a ticket to freedom.

I couldn’t tell if it was working at first. But then I started waking up earlier. Spending at least half an hour on devotions before I got up. Even praying again.

I wasn’t anxious for twelve hours before I went to work. I didn’t snap at my brother as much. I gave up one of my OCD rituals, a ritual I’d followed for years, with hardly a second thought. I created a bedtime routine and stuck to it.

It sounds simple, but to a person who was trapped for so long… it’s a miracle.

Today I am so grateful. And I want to tell people, but then I remember.

I’m taking a pill. A psychological pill. A pill from a doctor that changes my chemicals and not my heart. A pill that doesn’t have Jesus’ name or fasting or prayer written on it.

And I feel the words retreating to a quiet place inside me.

– – –

I’ve often found myself wondering: where does mind end and spirit begin? Would I be a different person without my mental disorders? How much am I shaped by this mind that I have? Does my mind define me?

How I answer these questions tells me who to blame. If the problem is in my mind, and if my mind isn’t me, then those disabling disorders—depression and anxiety and OCD—they aren’t my fault. But it seems like I am both: mind and soul, soul and body. All I can define of me is what I see and experience and know in my own head.

And if it wasn’t in my mind—if all of these struggles were purely spiritual—then I should be seeking help in prayer and not in medication.

But the medication works. Sure, prayer can help, but honestly… I haven’t felt this healthy—the kind of healthy you feel on the inside—in a long time.

“You know what I think?” one of my friends says. “I think the medication silences what’s wrong in your body so that your spirit can go free.”

And it makes sense, somehow, that my spirit is hurting because it’s stifled in this body, and all of it works together, just like all things work together for the good of those who love Him.

I don’t know what causes depression or anxiety. I don’t know how much of it is flesh and blood and how much of it is in the spiritual realm. But what I do know is that this mental freedom, this diagnosis, this antidepressant pill—this is helping. Not just my mind, but my spirit.

Psychological or otherwise, these pills are helping me reclaim my life.

I thank God for the pills. I thank God that the antidepressants are working. I thank God that I am beginning to live a life I enjoy.

Jesus came to give me “life, and life abundantly,” didn’t he?

– – –

All of these years I have felt like I am the one to blame for my own pain. The mental health awareness campaign says otherwise. It says that there is a name for the pain, and a logical, chemical reason for the pain, and a treatment for the pain.

What it doesn’t talk about is setting your spirit free.

Christians are often all about the spirit and not about the body. The effort goes into doing more righteous stuff instead of into healing. But the amazing thing is that Jesus didn’t do things in that order. He said to first love him, then obey him. He healed people, and then he told them to get up and tell others their testimony.

He loves and heals first, regardless of how we’re measuring up spiritually. He sets us free first, and then enables us to grow into his likeness.

Perhaps the psychologists focus too much on the mind and the Christians focus too much on the spirit. Perhaps we have forgotten the beautiful intersection between the two. And perhaps we, as Christians, have unintentionally kept the spirits of our friends and families trapped beneath the weight of a mental disorder they can’t control.

Getting a diagnosis and a treatment for a mental disorder is relief. It’s a clear-cut explanation of what’s gone wrong in your body. That diagnosis means that it’s not your fault—it’s just your chemicals. What a weight that lifts! It is far more comforting than “Pray harder, read your Bible more, and just have more faith.”

I used to be so angry at God. I fought so hard every day to try to “beat” my disorders. I needed to have victory. I was a person of faith, a strong woman of the Lord. I thought that someday I would finally learn some spiritual truth that would just “click” inside me and make everything that was wrong inside me right again. But no matter how much I prayed or studied, I couldn’t find it. I kept hearing God loves you, God loves you, God loves you, but it didn’t “fix” me. There had to be more. There had to be something I wasn’t getting.

So I kept begging: God, I try so hard, I always try so hard. Why am I still like this? Why haven’t you fixed me? Where are you?

And I still wasn’t healed.

Over the summer, I felt myself pulling away from God. I knew it was wrong, but I just didn’t have anything to say to him anymore. The moments when I sat down to pray felt like the loneliest moments of my life. I couldn’t think of anything to say except to keep asking and asking and asking, Where are you, God? Where are you? No response but silence, my heart hurting more than before. So I just stopped.

Eventually I couldn’t think of anything to write on the blog. I tried to write about why I wasn’t writing. I tried to write about my plans for the future. I tried to write about people Christians had rejected, while still feeling like God had rejected me.

My therapist finally told me that my depression was probably chronic—that I’d have to live with it on and off for the rest of my life. That was the first and only time I cried in her office. That was the moment when I realized that there was no point in fighting depression. I couldn’t get rid of my mental disorders.

Suddenly I was free. I didn’t need to be a “strong faith girl”. I didn’t have to find the answers. I didn’t have to fix myself. I couldn’t fix myself. There was nothing to blame God for and nothing to blame myself for.

At last it was okay to take medication. It wasn’t something I had to be ashamed of.

It’s still hard to talk about, but it’s getting easier. I want my friends to know that it’s okay to hurt. I want them to know that they shouldn’t let shame trap them. I want them to know that there is freedom when you admit what’s wrong, freedom when you accept that it’s not your fault, freedom when you work towards health—whatever that looks like.

Because now—my body is silent and my spirit is free. I’m free to do the things I once felt I had to do. I want to know God and I want him to lead my life. I am grateful that I get to spend time with him, grateful that I’m finally able to rest in his mercy, grateful that I can love him freely.

Best of all, I’m not angry at God. I no longer feel obligated to love him. I no longer feel like I constantly need to be fixed. I feel free to love him and seek him and participate in his plan for my life. I feel free to follow him as it comes naturally. I feel free to fall down and get back up again, to experience a whole range of emotions and no longer be ashamed.

My mental pain was blinding me to the freedom I have in Christ. I am so grateful that the blindfold has been lifted.