Sara Cahill Marron's Blog

November 17, 2025

On Writing Poetry, by Allen Ginsberg (July 2, 1984)

A recent query to a form I had long forgotten was floating around out there on the internet reminded me of this spreadsheet where I collect creative tools, inspiration, things to come back to, lectures, and all sorts of other little tidbits.

With this post, I’m starting a new section that will remain free for sharing these resources. They are, naturally, perfectly available without subscribing to this Substack (just perform the traditional google)—however, when I’m in need of a creative dusting, I often find that I don’t know where to begin. Thus, the accumulation of this little sheet of starting points.

To begin—an audio recording from a class taught by Allen Ginsberg on writing poetry. Enjoy!

SummarySecond half of an Allen Ginsberg class on writing poetry. He begins by referring to William Carlos Williams’s exhortation, “No ideas but in things,” comparing it to Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche’s statement that “Things are symbols of themselves.” He reads from Shakespeare’s poetry to illustrate his point. During the lecture, Ginsberg also touches on Haiku, Kerouac, and other topics.

Reproduced here, without alterations under Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs-NonCommercial 1.0 Generic License. Originally taped at the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics (1984).

November 3, 2025

The Art and Science of Scansion

Scansion is the method by which we analyze the rhythmic structure of a poem. It is crucial to approach it not as a rigid, mathematical exercise but as an interpretive practice that balances objective rules with subjective auditory sensitivity.

Effective scansion is a recursive, hypothesis-driven process. The analyst (you) moves between the raw auditory data (the sound of the line as spoken) and the abstract rules of prosody, progressively refining their "score" of the line until it represents the most plausible, expressive, and aesthetically satisfying reading.

This section lays the ground work for the practice of scansion and is designed to move from the general to the specific, beginning with the intuitive feel of the poem's rhythm and gradually applying more formal rules to arrive at a precise metrical identification. Next week, I’ll share a post with practice exercises. You can feel free to delete it immediately if the work triggers unwanted memories of grade school.

Step 1: The Auditory Pass – Trusting Your EarBefore making a single mark, the first and most important step is to engage with the poem aurally. Read the line, the stanza, and if possible, the entire poem aloud several times. The goal of this initial pass is not to analyze but to internalize the poem's natural cadence. Listen for what Annie Finch calls the "swing of the meter"—the dominant rhythmic pulse that emerges from the language. As you read, you can tap your hand or foot to the beat to help identify the primary stresses. Pay attention to which syllables your voice naturally emphasizes and which it passes over more lightly.

October 5, 2025

VII. Tradition & Subversion: The Art of Breaking Form in Contemporary Poetry

The landscape of contemporary poetry is a territory defined by the dynamic interplay between tradition and innovation. While the foundational techniques explored throughout this series remain the bedrock of the craft, today’s poets are constantly discovering new ways to deploy, combine, and, most significantly, subvert them. This final installment explores the art of subversion, arguing that the act of challenging established forms is not merely a stylistic flourish but a central and necessary strategy for creating vital new meanings in our rapidly changing world.

The Art of SubversionIn a literary context, subversion is the art of undermining established norms and expectations. It is a deliberate method of questioning dominant ideologies by deploying a range of techniques designed to disrupt the reader's passive consumption of a text. Poets achieve this through the careful use of irony, which conveys a meaning opposite to the literal; satire, which critiques societal norms through ridicule; and parody, which imitates another’s style for critical effect.

This disruption can also be structural. A non-linear narrative can challenge our notions of time and causality, while complex characters can dismantle stereotypes. In poetry, this often manifests as a playful yet pointed defiance of convention. Consider the subverted rhyme, where a poet sets up the expectation of a common or taboo word, only to pivot to an unexpected one. This technique uses humor and innuendo to engage the reader in completing the thought, implicating them in the poem’s wit and turning the act of reading into a collaborative discovery.

Formal Subversion as a Political ActThe most potent form of subversion in contemporary poetry often lies in the manipulation of form itself. For many 21st-century poets, particularly those from marginalized communities, subverting a traditional poetic form is a powerful political and philosophical statement.

The established forms of English poetry—the sonnet, the villanelle, the ballad—carry the weight of a literary history that has often been exclusive and patriarchal. When a contemporary poet engages with one of these forms, they enter into a dialogue with that entire history. The decision to intentionally break its rules—to fracture the meter, disrupt the rhyme scheme, or shatter its stanzaic integrity—becomes an assertion of agency.

This act transforms the poem’s structure into a metaphor for its content. A poet exploring the fragmented nature of immigrant identity might write a broken sonnet. A poet challenging the constraints of gender might write a villanelle that refuses to be contained by its repeating lines. The refusal to adhere to the form’s rules mirrors a refusal to be defined by the social structures that the form represents, turning the poem into a performative act of resistance and self-definition.

Case Studies in Contemporary PoeticsThe following poets demonstrate how a mastery of poetic technique provides the foundation for profound and subversive innovation.

Ocean Vuong: The Poetics of Trauma and SurvivalOcean Vuong’s acclaimed collection, Night Sky with Exit Wounds, is a searing exploration of war, migration, and queer identity. His technique is characterized by visceral imagery that refuses to let the reader look away. In his poem "Headfirst," a mother’s instruction becomes a devastating thesis on inherited trauma:

Text within this block will maintain its original spacing when published When they ask youwhere you're from, tell them your namewas fleshed from the toothless mouth of a war-woman.That you were not born— but crawled, headfirst— into the hunger of dogs.My son, the body is a blade that sharpens by cutting.Here, the body is not a site of peace but a weapon forged in violence. Vuong frames the Vietnam War as the paradoxical origin of his own existence with a stark and unflinching calculus. His innovation lies in crafting lines of exquisite lyrical beauty from subjects of profound horror, creating a poetics where survival itself is a form of defiant art. Horror poetry, anyone?

Ada Limón: The Embodied Symbolism of CarryingAda Limón, the current U.S. Poet Laureate, uses a poetics of embodied symbolism in her collection The Carrying to explore infertility, chronic pain, and our place in the natural world. The book’s central symbolic thread is established in the title poem, where the speaker’s observation of a pregnant mare prompts the pivotal question: "What if, instead of carrying / a child, I am supposed to carry grief?" This line transforms the physical act of "carrying" into a powerful, multifaceted symbol for the burdens we all bear: the weight of aging parents, the pain in our bodies, and a deep, often sorrowful, connection to the earth. Limón’s work is a masterclass in investing the specific, intimate details of a single life with universal resonance, exploring what it means to endure in a body that is at once a source of joy and a vessel for pain.

Natalie Diaz: The Body as a Postcolonial LandscapeIn her Pulitzer Prize-winning collection Postcolonial Love Poem, Natalie Diaz crafts a poetics where the personal body and the American landscape are inseparable. Her central symbolic act is to map the experiences of an Indigenous, queer body onto the wounded geography of the American Southwest. The Colorado River, dammed and endangered, becomes a recurring symbol for the violence enacted upon her people, their language, and their land. Diaz declares, “The Colorado River is the most endangered river in the United States—it is also my brother.” Her poems are acts of reclamation, where expressions of physical desire and love become powerful political statements. By refusing to separate the intimate from the historical, Diaz’s work is a masterclass in how embodied symbolism can challenge a colonial narrative, transforming the poem into a space of survival and defiant tenderness

Suzi F. Garcia: Subverting Form as Self-AnointmentSuzi F. Garcia's "A Modified Villanelle for My Childhood" is a prime example of formal subversion as a personal and political act. The villanelle is a highly structured, traditionally elegant form, which Garcia uses as a rigid container for a childhood marked by poverty ("With food stamps") and violence ("Fists to scissors to drugs to pills to fists again"). The tension between the restrictive form and the chaotic content creates a powerful dissonance. The poem adheres to the villanelle’s cyclical structure for eight stanzas, reflecting an inescapable struggle. In the final stanza, however, Garcia breaks the form. Instead of the traditional quatrain, she offers a defiant couplet that stands outside the rhyme scheme:

Text within this block will maintain its original spacing when publishedDid you know a poem can be both mythical and archeological? I ignore the cataphysical, and I anoint my own clavicle.

This final act of rebellion is a powerful assertion of agency. By refusing to complete the form, the speaker rejects the constraints of the world that has tried to define her. The final line—"I anoint my own clavicle"—is a declaration of self-creation, performed both thematically and structurally. Garcia's modification is not a failure to follow the rules; it is a deliberate subversion that embodies the poem’s theme of breaking free to claim one’s own identity.

Coda: The Enduring ArtificeOur journey through the poet’s artifice has taken us from the foundational elements of the craft to the sophisticated act of subversion. We began with the sensory architecture of imagery, the comparative logic of metaphor, the sonic signature of sound, how to measure a line through meter, the resonant depth of symbolism, and the conceptual core of theme. These are the timeless tools of the poet. They reveal a fundamental truth: poetry’s power lies not in stating meaning, but in enacting it.

To master these tools is to understand tradition. But to be a poet in the 21st century is to know when and how to break them. The modernist turn towards fragmentation and the contemporary focus on identity, technology, and justice are not arbitrary shifts in style; they are necessary responses to the evolving pressures of the world. Subversion, then, is not an act of destruction but of renovation. It is the engine of dialogue between the past and the present, a dialogue that keeps the art form fiercely alive.

As you move forward in your own reading and writing, hold this duality in your mind.

Learn the rules so that you may break them with intention.

The poet’s artifice, in all its complexity and beauty, remains our most indispensable means of navigating the world, challenging perception, and expanding our capacity for empathy. The fundamental human need to shape experience into meaning ensures that poetry, in whatever new forms it will take, endures.

Poet to poet: I believe in you. Keep writing—

Love,

Sara

September 28, 2025

VI. The Heart of the Matter - Uncovering and Analyzing Theme

The theme of a poem is its central argument, its underlying message, or its core insight into the human condition. It is the conceptual heart of the work, the "why" behind the poet's technical and artistic choices. Unlike a simple topic, which is the subject matter of the poem (e.g., love, war, nature), a theme is a specific assertion or exploration about that topic (e.g., that love is fleeting, that war is dehumanizing, that nature offers solace). The process of identifying and analyzing a theme is the ultimate goal of literary interpretation, as it involves synthesizing all of the poem's elements—its imagery, figures of speech, sound, and symbolism—to understand the total meaning it seeks to convey.

6.1 From Topic to Theme: A Methodology for AnalysisAnalyzing a poem's theme is not a matter of finding a single "hidden meaning" but of tracing how the poet builds a complex account of an idea. To perform thematic analysis, you can consider the following:

Identify the Topic(s): Begin by identifying the broad subjects or concepts the poem addresses. A poem can have multiple topics, such as love, death, and memory. Key questions to ask are: What is the topic of this poem? What are the large issues or universal concepts the poet is talking about?.

Formulate the Thematic Statement: Move from the general topic to a specific argument. The crucial question here is: What is the author trying to say about the topic?. This involves transforming the topic (e.g., "grief") into a thematic statement (e.g., "The poem argues that grief is a transformative process that reshapes one's identity").

Track Repetition and Motifs: Pay close attention to repeated words, phrases, images, or actions. Repetition is a key indicator of what the poet deems important and often highlights the central motifs that contribute to the theme. Ask: Are there any words, phrases, or actions that are repeated?

Point of clarification: The key distinction between motif/theme is that motifs are the recurring details that contribute to the theme. Stated another way, motifs are the building blocks, while the theme is the overall structure they help create.

Theme is defined as the central argument or message of the poem (e.g., "love is fleeting").

Motif is defined as a repeated element—such as a word, image, or action—that helps to build and reinforce that theme.

Synthesize the Poetic Devices: The most critical step is to analyze how the poem's literary devices work in concert to build, complicate, and reinforce the theme. How does the imagery create a specific mood related to the theme? How do the metaphors and similes shape the reader's understanding of the central concepts? How does the poem's sound and rhythm enact the theme on an auditory level? How do the symbols function as anchors for the abstract ideas? It is through this synthesis that a rich, evidence-based thematic analysis emerges. The goal is to explain how the author's literary choices help communicate the poem's message.

6.2 Insight: The Thematic Evolution of Contemporary PoetryThe dominant themes of poetry are not timeless or static; they evolve in direct response to the changing social, political, and technological landscapes of their time. While perennial topics like love, death, and nature persist, the way poets approach these subjects and the new themes that emerge are a direct reflection of the concerns and anxieties of their era. A clear trajectory can be traced from the early 20th century to the present, demonstrating how poetry functions as a sensitive barometer of cultural shifts.

The modernist period, reeling from world war and industrialization, was preoccupied with themes of alienation, fragmentation, and the loss of spiritual certainty. The postmodern era shifted focus to themes of identity, political instability, and cultural hybridity, deconstructing traditional narratives and questioning the nature of reality itself. Synthesizing findings on the contemporary period reveals another significant thematic evolution. 21st-century poetry shows a marked turn towards a new set of urgent concerns, directly caused by the conditions of modern life. The rise of globalization, the internet, ongoing struggles for social justice, and a growing awareness of ecological crisis have created new anxieties and experiences. In response, contemporary poetry has become a crucial space for exploring themes of fragmented and intersectional identity, the impact of technology on the self, the poetics of social activism, and the looming threat of climate change. This causal link is undeniable: the changing world creates new realities, which in turn demand new thematic explorations in its poetry.

6.3 The Major Themes of 21st-Century PoetryContemporary poetry is characterized by its diversity of voices and its engagement with the pressing issues of the modern world. Analysis of recent literary trends reveals several key thematic preoccupations that define the current moment:

Identity, Diversity, and Belonging

Perhaps the most dominant theme in 21st-century poetry is the complex exploration of identity. In a globalized, post-colonial, and digitally interconnected world, poets are grappling with questions of personal, racial, cultural, national, and gender identity with unprecedented urgency. This includes the anxiety of cultural homogenization in the face of globalization, the celebration of hybrid identities, and the use of poetry to give voice to marginalized experiences. Poets like Cathy Park Hong, known for her use of "code-switching" (mixing languages), explore the linguistic and cultural complexities of the immigrant experience. The focus has shifted from a stable, confessional "I" to a more fluid, constructed, and often politically charged sense of self.

Technology and the Digital Self

The pervasiveness of digital technology has become a major theme, with poets reflecting on its impact on human consciousness, community, and language. This includes the transient nature of poetry designed for online consumption, the exploration of "cyber-poetry" and hypertext, and how social media shapes identity and relationships. The digital world is no longer just a subject for poetry but is also fundamentally changing the forms and methods of its creation and dissemination.

Social and Political Commentary

There has been a powerful resurgence of politically engaged poetry, with poets using their work as a tool for social commentary, activism, and protest. This "poetry of witness" often responds to events like the "War on Terrorism," systemic racial injustice, and political polarization. It serves as a "discourse of resistance" against oppressive policies and social inequities, aiming to sensitize the public's conscience and call for change.

Eco-Poetics and the Anthropocene

A growing and powerful strain of contemporary poetry is dedicated to ecological concerns. Informed by the realities of climate change, species loss, and environmental degradation, eco-poetics explores humanity's fraught and often destructive relationship with the natural world. Poets like Mary Oliver find visionary intensity in nature, while others, like Gary Snyder, infuse their work with an environmental consciousness rooted in Zen Buddhism. This thematic focus reflects a collective anxiety about the future of the planet and seeks to foster a deeper respect for the environment.

These themes demonstrate that contemporary poetry is not an art form in retreat from the world but one that is actively and urgently engaged with it. Personally, I believe this—in the last five years, AI has often been sneered at, ridiculed, and feared by members of the literary community. However, language as a model for meaning is, indeed, what we as poets are all about, is it not? I continue to be fascinated by the construction of AI and LLMs, because they attempt to do what I believe is the core work of the poet: construct meaning using the signals of language.

6.4 Exercise: Argument with an ObjectThis exercise uses apostrophe (addressing an inanimate object) to uncover the underlying thematic questions you are truly interested in.

Read and Consider "The Clearing" by Carl Phillips. Observe how the speaker's intense focus on a physical space—the trees, the light, the path—becomes a meditation on desire, risk, and the nature of truth. The landscape is not just a setting but a silent partner in a philosophical inquiry.

Choose Your Object: Select an ordinary object in your immediate vicinity, something you might otherwise ignore. A radiator, a stain on the ceiling, a framed picture, a power outlet.

Start an Argument: Write a poem that speaks directly to this object. Ask it accusatory questions. Tell it your secrets. Blame it for something. Demand an answer from it. Use phrases like, "You think it's easy..." or "Don't you ever..." or "What did you see...".

Discover the Theme: After you've finished writing, read your poem back and ask: What was I really arguing about? An argument with a radiator about heat might really be about the theme of emotional coldness or neglect. An interrogation of a stain might be about the permanence of past mistakes. The object becomes a vessel for the theme, allowing you to explore it with more subtlety and power.

By tackling the most complex and challenging issues of our time, 21st-century poets (you!) reaffirm the art form's enduring power to articulate, question, and shape the human experience. Typically, I avoid engaging with the politics of the day online; however, the funeral held for Charlie Kirk this week has been stuck in my poetic mind for days.

Considering the exercise above, what was the theme of that performance?

What was the motif (vehicle) for expressing that theme?

The motif, in my view, was the memorial itself, the passages of scripture read/performed by those grieving the death. The theme utilized those motifs to convey a very specific message, which perverted the motif of funerary rites/personal grieving. In that mega-stadium, another type of grief had the perfect thematic stage to perform its persuasion. If you can answer below without political affiliation, what was the thematic grief expressed on that stage? How did that theme of grief/anger pollute the motif of the funeral itself and, in doing so, amplify the theme beyond the personal motifs that are intrinsic to funerals/memorial rites?

What are the other motifs / repeated images or concepts that are used often to accomplish that theme? Think about funerals/memorials you’ve attended. What are the repeated stories that are told that help us to conceptualize loss/understand and integrate the theme of death? How did the Kirk broadcast capitalize on the universal motifs of funerary rites to accomplish a particular theme? (Truly a little nervous to post this—but I hope you all see what I’m driving at, with these prompts. If nothing else, as poets, we should constantly be scrutinizing the manner and method through which we consume information.)

As this series is coming to a close, I urge you to continue to revisit your fears, in all their forms. Look directly at those tenets of the craft that spur resentment and frustration. Practice your craft with all the seriousness of a machine building a repository of meaning, and eventually, you will do what that machine cannot: become a filter of art through the experience of consciousness.

Subscribe to get part VII, The Contemporary Turn - Innovation and Subversion in 21st-Century Poetics, delivered to your inbox next week.

September 21, 2025

V. The Resonance of the Concrete - Symbolism and Its Layers

Symbolism is a literary device of profound resonance, allowing poets to convey complex ideas, emotions, and themes by investing a concrete object, color, or image with abstract significance. It operates on a level beyond the literal, inviting the reader to engage in an act of interpretation and reflection, thereby adding depth and complexity to the poetic work. It is a bridge between the tangible world of the senses and the intangible world of ideas, enabling poets to express what might otherwise remain ineffable. Confused yet? Let’s dive deeper.

5.1 Defining the Symbol: An Enduring, Resonant ImageAt its core, a symbol is a concrete image that stands for an abstract concept. A heart symbolizes love; a dove symbolizes peace. While it shares a comparative function with metaphor, symbolism operates differently. A metaphor is typically a direct, often singular, comparison that equates two unlike things ("Juliet is the sun"). A symbol, in contrast, tends to be a central, often recurring image within a text, whose meaning accrues and deepens with each appearance. It is an enduring and resonant image that serves as a touchstone for the work's primary themes.

This principle is vibrantly alive in contemporary poetry. Ocean Vuong’s work, both in poetry and prose, is full of symbolic imagery. In his novel On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, the orchid, for instance, appears throughout as a fragile emblem of memory, inheritance, queer beauty, and survival in the face of pain. Vuong doesn’t define the orchid; he lets it gather meaning through repetition and placement, trusting the reader to feel its weight. Similarly, the monarch butterfly, a creature known for its epic, multi-generational migration, becomes a powerful symbol for the immigrant experience, connecting generations across vast distances and historical trauma.

Ocean—if you’re out there reading—I adore your poetry, bravo bravo bravo.

5.2 A Typology of Symbols: Conventional, Contextual, and PersonalSymbols in poetry can be categorized into three main types, each with a different source for its meaning:

Conventional Symbols: These are symbols whose meanings are widely accepted and understood across cultures and time periods. They draw on a shared reservoir of cultural knowledge. Examples include the rose symbolizing love or passion, the snake representing transformation or deceit, and the cross symbolizing Christianity or sacrifice. Poets use conventional symbols to tap into universal themes and ideas, sometimes reinforcing their traditional meaning and other times subverting it for ironic or critical effect.

Contextual Symbols: Also known as literary symbols, these derive their meaning specifically from the context of the poem or the poet's body of work. Their significance is not universal but is established by the unique way they are used within the text. In T.S. Eliot's "The Waste Land," for example, the image of "dry land" or "stony rubbish" is not inherently symbolic, but within the poem's landscape of spiritual decay, it becomes a powerful contextual symbol for sterility and desolation. The meaning is built and contained entirely within the world of the poem.

Personal (or Accidental) Symbols: These symbols are unique to a particular poet's work and often reflect their personal experiences, obsessions, or psychological states. The theorist Erich Fromm termed these "accidental" symbols because their meaning arises from a specific, individual association rather than a universal or conventional one. A prime example is Sylvia Plath's use of the "bell jar" as a recurring personal symbol for her suffocating struggles with mental illness. Exploring these personal symbols often reveals the most about the unique vision of the poet and can create a powerful sense of intimacy with the reader.

5.3 The Symbolist Legacy and the Modernist MindThe emphasis on suggestive, multi-layered symbolism in modern poetry owes a significant debt to the 19th-century French Symbolist movement. Poets like Charles Baudelaire, Stéphane Mallarmé, and Arthur Rimbaud revolted against the descriptive literalness of Realism and Parnassian poetry. They believed that the purpose of art was not to describe the external world but to express individual emotional experience and evoke the "underlying mystery of existence" through the subtle and suggestive use of highly symbolized language.

The Symbolists championed Baudelaire's concept of correspondances—the idea that the senses are interconnected and that a sound can evoke a color, or a scent a feeling. They combined this with a Wagnerian ideal of synthesizing the arts, leading to a new conception of the "musical qualities of poetry." For them, a poem's theme could be orchestrated through the careful manipulation of the harmonies, tones, and colors inherent in words. This belief in the supremacy of art as a means of glimpsing a deeper, subjective reality, combined with their experiments in vers libre (free verse), had a profound and lasting influence on 20th-century literature. The experimental techniques of the Symbolists directly informed the work of modernists like W.B. Yeats and T.S. Eliot, who prioritized patterns of images and word harmonies over straightforward narrative, fundamentally changing the landscape of English-language poetry.

5.4 Case Study: The Symbolic Landscape of T.S. Eliot's "The Waste Land"T.S. Eliot's "The Waste Land" is arguably the pinnacle of modernist symbolic poetry, a work where the very method of its construction becomes a symbol for its theme. The poem famously presents the reader with what it calls a "heap of broken images," and this fragmentation is the central symbol for the cultural, spiritual, and psychological decay of the post-World War I Western world.

The poem operates through a series of powerful, recurring contextual symbols that create its bleak and desolate landscape:

Water and Rock/Dry Land: This is the poem's most fundamental symbolic opposition. Water consistently represents the possibility of life, purification, and spiritual rebirth, but it is almost always absent or corrupted. The poem is filled with images of sterility: "the dead tree gives no shelter, the cricket no relief, / And the dry stone no sound of water." The third section is titled "The Fire Sermon," and the fifth, "What the Thunder Said," presents "dry sterile thunder without rain." The inhabitants of the waste land are spiritually thirsty, living in a world of "mountains of rock without water." This symbolic drought represents the loss of faith and meaning in the modern era.

The Unreal City: Eliot uses this phrase to describe a vision of London that is both physically real and spiritually dead. The image of a crowd flowing over London Bridge is populated by the damned from Dante's Inferno: "A crowd flowed over London Bridge, so many, / I had not thought death had undone so many." This city is a symbol of the hollow, alienated nature of modern urban life, a place of mechanical existence devoid of genuine human connection.

Fragmentation: The poem's very structure—its collage of different voices, its abrupt shifts in time and place, its inclusion of multiple languages and literary allusions—is itself a symbol. The "heap of broken images" is not just a description of the waste land; it is the waste land, rendered in poetic form. The fragmentation symbolizes the collapse of traditional cultural narratives, the loss of a shared system of belief, and the disjointed nature of modern consciousness.

In "The Waste Land," symbolism and theme are inextricably intertwined. Eliot does not tell the reader that the modern world is spiritually bankrupt; he constructs a symbolic landscape where every image—from the "dead tree" to the "empty chapel"—embodies that bankruptcy. The poem is a powerful testament to how a sophisticated system of contextual and conventional symbols can be used to diagnose the spiritual condition of an entire civilization.

5.5 The Symbol in Contemporary Poetry: Nature, Body, and IdentityWhile the influence of modernism remains, contemporary poets have expanded the use of symbolism to explore urgent themes of identity, ecology, and social justice. They often ground their symbols in the tangible, the bodily, and the natural world, creating work that is both intensely personal and politically resonant.

Ada Limón: As the current U.S. Poet Laureate, Limón frequently turns to the natural world to forge her symbols. In her collection The Carrying, the horse becomes a complex personal symbol. It represents not just raw power and nature, but also bodily frailty, the desire for connection, and the struggle to carry on amidst grief and infertility. For Limón, an animal or a plant is never just a backdrop; it is an active participant in the poet's emotional life, becoming a vessel for complex, often contradictory, feelings.

Natalie Diaz: In her Pulitzer Prize-winning collection Postcolonial Love Poem, Diaz uses the Colorado River as a profound contextual symbol. She revitalizes the conventional symbol of water as life, infusing it with her perspective as an Indigenous Mojave woman. The river, endangered by American development, becomes a symbol for the wounded but enduring body of her people, for language, for desire, and for a love that resists colonial erasure. Her lines, "The river runs through me, not the other way around," assert a deep, symbolic connection between body, land, and identity. The water is not just a symbol for these things; it is these things, inseparable and sacred. (I’m obsessed, Natalie).

These poets demonstrate how symbolism continues to be a vital tool. They take conventional symbols and filter them through personal and cultural lenses, creating new layers of meaning that speak directly to the complexities of our current moment.

An Exercise on Cultivating Your Own SymbolsThis exercise is intended to help you move from understanding symbolism to using it in your own work. The goal is to create a short poem where a symbol's meaning is revealed through context, not explanation.

Step 1: Brainstorming Your Symbolic “Inventory”Take 10 minutes to brainstorm in three categories, based on the typology above. Don't overthink it or judge what inventory is in your mind today at this moment; just list what comes to mind.

Conventional Symbols: List 5-10 common symbols you know (e.g., a key, a chain, a road, a storm, a seed, a window).

Personal Objects: List 5-10 concrete objects that hold personal meaning for you. Think specific! Not just "a car," but "my grandfather's rusted Ford pickup." Not "a cup," but "the chipped blue mug I use every morning."

Memorable Places/Images: List 5-10 specific places or images from your memory (e.g., the streetlight outside your childhood bedroom, a dead tree in a field, the pattern of a tiled floor).

Step 2: Choose Your CoreReview your lists. Now, select one abstract concept you want to write about (e.g., nostalgia, freedom, grief, connection, anxiety).

Next, choose one concrete image from your "Personal Objects" or "Memorable Places" list that you feel could connect to this abstract concept, even if you don't know exactly how yet. The less obvious the connection, the more interesting it might be.

Example: Concept = Grief. Image = The chipped blue mug.

Step 3: Develop the Symbol Through Sensory DetailInstead of telling the reader what your symbol means, you're going to show it. On a separate page, describe your chosen object or image using at least four of the five senses.

What does it look like? (Color, texture, light, shadow)

What does it sound like? (Or what is the sound of the silence around it?)

What does it feel like? (Temperature, weight, texture)

What does it smell or taste like? (English is highly deficient in these adjectives, use metaphor freely)

What actions are associated with it? (Being held, being watched, being opened, rusting away)

Step 4: Draft the PoemWrite a short poem (10-20 lines) that includes your symbol. Follow these guidelines:

NEVER explain what the symbol means. Do not use phrases like "the mug represents my sadness."

Mention the symbol at least twice.

In its first appearance, just describe it or place it in the scene.

In its second appearance, try to show its connection to the abstract concept through action, memory, or feeling.

Example Draft:

The kitchen is cold this morning. My hands wrap around the chipped blue mug, feeling the crack near the handle like a familiar scar.

Later, I see it on the drainboard, empty, holding the quiet echoes of steam.

Read your poem aloud. How did the meaning of your symbol change or deepen from the first mention to the second? By focusing on concrete details and allowing the symbol to exist without explanation, you invite the reader into the act of discovery, creating a more powerful and resonant poem. And—my favorite piece of writing poetry—you’ll be building a new world you invite any reader into, a stanza of your own, if you will allow me the bad pun.

Subscribe to get Part VI, The Heart of the Matter - Uncovering and Analyzing Theme, delivered to your inbox next week.

September 14, 2025

IV. Meter: The Measure of the Line

At its core, poetry is an art form rooted in sound. Part III: Rhythm, provided an overview of the history of poetic lyricism—long before poems were written down, they were spoken, chanted, and sung. The rhythmic quality of a poem is what gives it a musicality that can captivate a listener, evoke emotion, and create a memorable experience. This internal pulse is known as its rhythm, and the formal, organized system of that rhythm is called meter. Understanding how to identify and analyze a poem's rhythm is a fundamental skill for any reader of poetry, as it unlocks a deeper appreciation for the poet's craft.

The study of poetic rhythm, or prosody, is a discipline dedicated to understanding the organized patterns of sound that distinguish verse from prose. While prose certainly possesses its own cadences, the rhythm of poetry is characterized by a heightened degree of structure, a deliberate and artful arrangement of sonic elements that contributes fundamentally to the work's aesthetic and semantic power. To engage in a rigorous analysis of this phenomenon, it is essential to establish a precise vocabulary for its constituent parts. The architecture of poetic rhythm is built upon four foundational concepts: rhythm itself, the abstract framework of meter, the linguistic reality of stress, and the analytical practice of scansion.

The aesthetic power and semantic richness of metrical poetry are generated in the dynamic interplay—a form of productive tension—between the abstract regularity of the meter and the variable, nuanced rhythm of the spoken language.

The meter acts as a silent, structuring principle, a "ghost" pattern that creates an expectation in the reader's ear.

The rhythm, composed of the actual sounds of the words chosen by the poet, is how that expectation is either fulfilled, subverted, or complicated. This interaction can be understood as a dialectical process.

Another way to think about it:

The meter provides a thesis—the expected pattern of beats. The natural rhythm of the words, with their unique phonetic properties, provides an antithesis—the actual pattern of spoken emphasis.

So, what does this all mean? To me, it means that the most significant and expressive moments in a metrical line are often the points of greatest tension, where the rhythm deviates most noticeably from the underlying meter. These variations are not poetic failures or errors; they are, in the hands of a skilled poet, deliberate artistic choices designed to create emphasis, surprise, emotional texture, or to mimic the natural cadences of speech. The purpose of scansion, then, is not simply to confirm that a line adheres to its meter, but to analyze this "counterpoint" between the ideal and the actual. It is an interpretive act aimed at uncovering how a poet manipulates the metrical framework to shape meaning, transforming a simple classification system into a powerful analytical tool for literary interpretation.

4.1. Defining the Core Quartet: Rhythm, Meter, Stress, and ScansionThe terms rhythm and meter are often used interchangeably in casual discourse, yet in formal prosody, they denote distinct, albeit interrelated, concepts. The distinction between them is crucial, as it is in the interplay between the two that much of the artistry of metrical verse resides.

Rhythm is the most encompassing of the terms, referring to the overall auditory experience of a poem—its flow, its movement, its musicality. It is the palpable, temporal structure of the language, arising from the natural alteration of stressed and unstressed syllables as the words are spoken. Rhythm is a quality inherent in all language, but in poetry, it is more highly organized, patterned, and foregrounded as an element of artistic design. It is the cumulative effect of all sonic features, including pace, pause, and syllabic emphasis, that creates the unique cadence of a given line or stanza.

Meter, in contrast, is the abstract, idealized pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables that serves as the blueprint for a line of verse. It is a cultural and artistic construct, a system that regularizes the natural rhythms of language into a predictable sequence. Meter is defined by the repetition of a basic unit of measurement called a

Metrical foot, which is a specific grouping of stressed and unstressed syllables. A poem is said to be "in a meter" when its lines consistently adhere to a particular type and number of metrical feet. For example, the most common meter in English poetry, iambic pentameter, prescribes a line containing five iambic feet. Meter is the underlying grid, the expected beat against which the actual rhythm of the words plays out.

Stress is the relative emphasis given to a syllable in pronunciation. A critical distinction must be made between linguistic stress and metrical stress. Linguistic stress is the natural emphasis a syllable receives in ordinary speech, determined by lexical and syntactical context. For instance, in the word "destroy," the second syllable is naturally stressed. Metrical stress, often called ictus, refers to the position within the abstract metrical pattern that is designated as stressed. In a perfectly regular line of iambic pentameter, the ictus falls on every second syllable. The analysis of poetic rhythm involves examining how the natural linguistic stresses of words align with, or deviate from, the expected positions of metrical ictus.

Scansion is the analytical practice of determining and graphically representing the metrical pattern of a line of verse. It is the methodology used to "scan" a poem, marking its stressed and unstressed syllables, dividing the line into its constituent feet, and thereby identifying its meter. Scansion is not merely a mechanical exercise in labeling; its ultimate purpose is to make the poem's rhythmic structure visible, allowing the analyst to enhance their sensitivity to the ways in which rhythmic elements convey meaning and to identify significant deviations from the established pattern.

To conduct a formal scansion, a standardized set of symbols is employed to represent the rhythmic components of a line graphically. This notational system allows for a clear and consistent analysis of metrical patterns. The essential symbols are:

The Breve ( ˘ or u ): This symbol, resembling a small cup, is placed over a syllable to indicate that it is unstressed, weak, or "nonictic" (not occupying a position of metrical stress).

The Ictus or Wand ( ´ or / ): This symbol, a forward slash or accent mark, is placed over a syllable to indicate that it is stressed, strong, or "ictic" (occupying a position of metrical stress).

The Foot Boundary ( | ): A single vertical line is used to mark the division between metrical feet within a line of verse. This visually separates the repeating units of the meter.

The Caesura ( || ): A double vertical line indicates a caesura, which is a significant pause or break within a line of poetry. A caesura is typically created by punctuation (such as a comma, semicolon, or period) but can also be dictated by the natural syntax and phrasing of the line.

These symbols provide the visual language necessary to deconstruct and analyze the intricate sound structures of metrical verse.

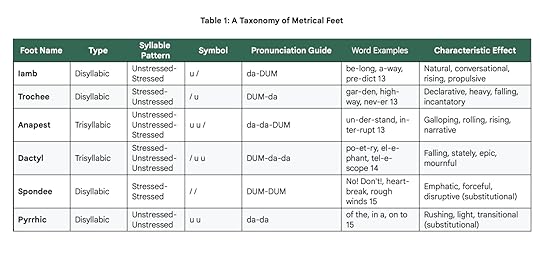

4.2 The Building Blocks of Meter: A Taxonomy of Poetic FeetThe classification of metrical feet is not merely a descriptive exercise; it reflects a fundamental energetic and psychological principle inherent in their structure. Feet can be categorized into two primary modes—rising and falling—based on the placement of the stressed syllable. This choice of a dominant rising or falling meter is a primary structural decision by the poet, establishing the poem's core momentum and emotional posture before the specific meaning of any single word is even considered.

Rising Rhythms, characteristic of the iamb (u /) and the anapest (u u /), begin with unstressed syllables and build toward a stress. This progression from a state of lower energy to higher energy creates a natural sense of anticipation, propulsion, and forward movement. The iambic foot, with its da-DUM pulse, closely mirrors the natural cadence of English speech, making it feel conversational and familiar. The anapest, with its da-da-DUM pattern, accelerates this rising motion, creating a "galloping" or rolling rhythm well-suited for narrative verse and ballads. The kinesthetic sensation of a rising meter is one of building toward a destination, of gathering energy for a climactic release.

Falling Rhythms, found in the trochee (/ u) and the dactyl (/ u u), reverse this dynamic. They begin with a stressed syllable and then recede or "fall" to unstressed syllables. This movement from high energy to low energy produces a very different psychological effect. The trochaic foot (DUM-da) is forceful, declarative, and emphatic. It is the rhythm of commands, chants, and incantations, starting with impact and then diminishing. The dactylic foot (DUM-da-da) possesses a grander, more stately falling motion. It is often associated with the epic tradition of classical poetry and can evoke a tone of solemnity, gravity, or mournfulness. The physical sensation of a falling meter is one of assertion or finality, like a pronouncement or a sigh. A poet's selection of a dominant rising or falling meter, therefore, establishes the fundamental "gait" of the poem, shaping the reader's subconscious experience of its energy and emotional direction.

While the four feet described above can form the dominant meter of a poem, the spondee and the pyrrhic function almost exclusively as tools of metrical substitution. They are rarely, if ever, used to construct an entire line of verse, as a line of pure spondees or pure pyrrhics would lack the alternating pattern of stress and unstress that defines meter. Instead, they are strategically inserted into lines of a more regular meter to create variation and emphasis.

A spondee (/ /) consists of two consecutive stressed syllables. Its function is to disrupt the established rhythm and force heavy emphasis onto a pair of words or syllables, thereby slowing the pace of the line and creating a powerful, often jarring, effect. For example, in Alfred, Lord Tennyson's "Ulysses," the line "To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield" gains much of its resolute force from the spondees that break the iambic pattern. Similarly, the opening of his poem "Break, Break, Break" uses three consecutive spondaic feet to convey the immense, percussive power of the waves.

A pyrrhic (u u), conversely, is composed of two consecutive unstressed syllables. Its effect is to lighten and accelerate the rhythm of a line. A poet might substitute a pyrrhic for an iamb to de-emphasize a pair of function words (such as "of the" or "in a"), allowing the line to rush more quickly toward the next significant metrical stress. This creates a sense of swiftness or transition, preventing the meter from becoming ploddingly regular and allowing for a more fluid and natural-sounding rhythm. These two substitutional feet are essential tools that allow the poet to achieve rhythmic variety and rhetorical force within a structured metrical framework.

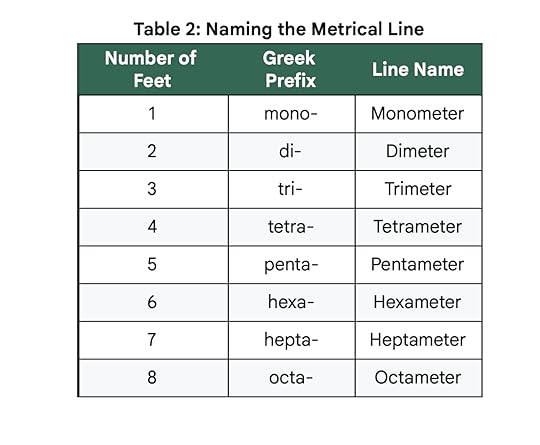

Once the fundamental unit of the metrical foot is understood, the next step in prosodic analysis is to examine how these feet are assembled to form a complete poetic line.

The identity of a metrical line is determined by two components: the predominant type of foot it contains (its quality) and the number of these feet present in the line (its quantity). The standardized nomenclature for describing meter combines these two elements into a single, precise descriptive phrase, such as "iambic pentameter" or "trochaic tetrameter"

The quantitative aspect of a metrical line—its length—is described using terms derived from Greek prefixes that denote numbers. A line's name is formed by combining the appropriate prefix with the word "meter." This system provides a consistent and universal vocabulary for classifying line lengths across different poetic traditions. The following table outlines the standard terms for the most common line lengths in English poetry.

By combining the adjectival form of the foot name (from Table 1) with the appropriate line name (from Table 2), a complete and precise description of a regular metrical line can be achieved. For example, a line containing five iambs is called iambic pentameter; a line containing four trochees is called trochaic tetrameter.

The length of a poetic line is not an arbitrary aesthetic choice but a formal constraint that profoundly influences the poem's character. It directly correlates with the poem's pacing, its potential for syntactical complexity, and its thematic scope. Shorter lines, such as dimeter and trimeter, are often found in lyrical poems, songs, and nursery rhymes. Their brevity necessitates simpler syntax and creates a rapid, light, or sometimes fragmented and breathless tone. Longer lines, by contrast, accommodate more complex grammatical structures, including subordinate clauses and parenthetical phrases.

Pentameter, the five-beat line, is celebrated for its versatility, capable of containing a complete, complex thought while retaining a natural, speech-like cadence. This balance makes it the ideal vehicle for the sophisticated arguments of sonnets and the elevated dialogue of Shakespearean drama. Even longer lines, such as the six-beat

Hexameter, are explicitly linked to the grand, narrative scope of the epic tradition, as seen in the works of Homer and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. The hexameter's expansive capacity allows for sweeping descriptions and a grave, meditative tone. Thus, a poet's choice of line length is a primary signal of their intended genre, tone, and the intellectual complexity of their subject matter. It shapes the reader's cognitive engagement by defining the size and complexity of the "thought-units" they process with each line of verse.

4.3 The Symbiosis of Sound and Sense: How Rhythm Creates MeaningThe ultimate goal of prosodic analysis is not simply to label a poem's meter but to understand how that meter functions as an integral part of the poem's total meaning-making apparatus. Rhythm is not a decorative flourish applied to the surface of a poem; it is a fundamental structural element that shapes, reinforces, and sometimes complicates the poem's thematic content. This relationship can be analyzed through a framework of concordance and dissonance.

In concordance, the sound echoes the sense, with the rhythm amplifying the poem's mood and message.

In dissonance, the rhythm creates an ironic or unsettling contrast with the content, generating a more complex and layered meaning.

A full literary interpretation requires an ear attuned not just to what the words say, but to the music they make as they say it.

More on ConcordanceThe most straightforward relationship between rhythm and meaning is concordance, where the metrical form directly reinforces the poem's subject and tone. The sound becomes an echo of the sense. A poem about a galloping horse might use a galloping anapestic meter; a solemn elegy might employ the stately, falling rhythm of dactyls. In these cases, the meter is not merely a container for the meaning but an active agent in its creation, allowing the reader to feel the poem's subject in its very pulse.

More on DissonanceCase Study: The Trochaic Oppression of Poe's "The Raven"

Edgar Allan Poe's "The Raven" is a masterclass in the use of metrical concordance to create an overwhelming and inescapable mood. The poem is written in a relentless trochaic octameter, a meter whose characteristics are perfectly suited to the poem's themes of oppressive grief, maddening repetition, and psychological entrapment.

The trochee (/ u) is a falling meter, beginning with a heavy stress that immediately recedes. Repeated over the long, eight-foot line, this DUM-da rhythm creates a heavy, plodding, and incantatory effect. It is a rhythm of weary insistence, mirroring the narrator's own mental state as he is "weak and weary".

Text within this block will maintain its original spacing when publishedOnce upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered weak and weary,Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore,While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping,As of some one gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door.''Tis some visitor,' I muttered, 'tapping at my chamber door -Only this, and nothing more.'

A more complex and often more powerful relationship between rhythm and meaning occurs through dissonance. In this mode, the poet deliberately creates a clash between the mood suggested by the meter and the mood suggested by the subject matter. A light, cheerful, sing-song meter might be used to narrate a story of violence, tragedy, or horror. This ironic contrast can produce a deeply unsettling effect, suggesting a world where terrible events are commonplace, a speaker who is emotionally detached, or a satirical critique of a seemingly innocent form.

Poets can also manipulate the rhythm of a line by altering its expected syllabic count at the very end. These variations affect the line's sense of closure and finality.

A Feminine Ending occurs when an extra, unstressed syllable is added to the end of a metrically complete line, most commonly an iambic line. For example, the final foot of an iambic pentameter line, which should be

u /, becomes u / u. This additional light syllable can create a softer, more lingering, or questioning effect. It leaves the line feeling less conclusive, as if it is trailing off into thought or sighing into silence. Shakespeare frequently used feminine endings in his later plays to create a more fluid and naturalistic verse that mirrored the less-structured patterns of speech.

Catalexis is the opposite phenomenon: the omission of an expected unstressed syllable from the end of a line. This technique is most common in falling meters like trochaic and dactylic verse. For example, a line of trochaic tetrameter, which would regularly end with a trochee (/ u), becomes catalectic when the final unstressed syllable is dropped, ending on a stressed syllable (/). This creates an abrupt, forceful, and highly conclusive stop. In fact, most trochaic verse in English is catalectic, as a series of complete trochaic lines can sound sing-song and unnatural; the catalectic ending provides a stronger sense of closure. A feminine ending leaves a line feeling unresolved, like an ellipsis, while a catalectic line feels final and emphatic, like a period.

A caesura is a strong pause or break within a line of verse, distinct from the pause that naturally occurs at the end of a line. It is a formal rhythmic device, often but not always marked by punctuation such as a comma, semicolon, colon, or period. The caesura is a powerful tool for controlling a poem's pacing and creating internal structure within a line. Its placement can dramatically alter the line's rhythm and meaning.

A medial caesura, the most common type, occurs near the middle of the line and can divide it into two balanced halves. This can create a sense of equilibrium or antithesis, juxtaposing the ideas on either side of the pause. An initial caesura occurs near the beginning of a line, while a terminal caesura occurs near the end. By breaking the expected flow of the meter, a caesura forces a pause for thought, mimics the hesitations and shifts of natural speech, or creates dramatic tension.

In Hamlet's famous soliloquy, the placement of the caesura is as meaningful as the words themselves:

[INSERT]

4.4 Rhythm as an Indispensable Element of MeaningThe analysis of poetic rhythm, from the identification of a single foot to the interpretation of a poem's overarching metrical character, is a fundamental component of literary study. Rhythm is far from being a mere ornamental feature. It is a complex system that operates in a symbiotic relationship with a poem's diction, syntax, and thematic concerns. The choice of a rising or falling meter establishes a poem's basic energetic posture. The length of the line helps to define its thematic scope and syntactical capacity. The strategic use of metrical variations provides a layer of rhetorical punctuation that guides emphasis and pacing.

Ultimately, the relationship between this rhythmic structure and the poem's content—whether one of concordance or dissonance—is a primary source of the work's power and complexity. The sound of a poem is an inseparable part of its sense. Therefore, a complete and nuanced interpretation of any metrical poem is impossible without a rigorous scansion and a sensitive ear, attuned not only to the meanings of the words but to the intricate and expressive music they make as they unfold in time.

Meter in the Modern Age: A Vestige of the Poetic Past?The modernist movement of the early 20th century is often characterized by its revolutionary break with the formal constraints of the past. Poets like Pound and Eliot championed free verse, and meter came to be viewed by many in the avant-garde with disdain, seen as an "automated metronome" that stifled authentic expression. This led to an "abstraction from meter to rhythm," where the focus shifted to the more organic, less rule-bound qualities of poetic sound.

However, this narrative of a clean break is incomplete. Many modern poets continued to write in meter, but they did so with a new self-awareness. The act of writing a sonnet in 1925 was fundamentally different from writing one in 1595. It was a choice freighted with historical consciousness. This tension is palpable in the work of poets who straddled the line between tradition and innovation. Robert Frost, for example, famously quipped that writing free verse was "like playing tennis with the net down," and he masterfully employed traditional meters to explore modern anxieties. In his work, the steady, familiar rhythm of blank verse often contains a deep sense of psychological unease, creating a powerful friction between form and content.

This complex relationship with meter continues today. While free verse remains the dominant mode, contemporary poets still engage with traditional forms, often to subvert them. A contemporary poet might write a sonnet about a subject that would have been considered "unpoetic" in a previous era, or they might intentionally disrupt the meter of a villanelle to reflect a fractured psychological state. In this way, meter remains a powerful tool in the poet's arsenal, not as a rigid set of rules, but as a historical and formal "vestige" that can be invoked, challenged, and transformed to create new and potent meanings.

This essay is long enough for now—but do we want a bonus post on scansion? Leave a comment if that would interest you! I would also love to hear from free verse friends and champions what their bellwether of rhythm is in poetry. Personally, I’ve gotten caught in the trap of “well, I can just tell” when pressed to define what makes rhythm lyrically in free verse poetry. However, one of the above elements is always at play (caesura, concordance, dissonance), and inevitably, a patternistic set of iambs that the poet, writing in free verse, has employed subconsciously.

Subscribe to get Part V: Symbolism directly to your inbox next week.

September 7, 2025

III: The Poem's Sonic Signature - Sound, Rhythm, and Musicality

Beyond the visual and conceptual layers of a poem lies its sonic architecture. Sound devices are literary tools in which the very sounds of the words themselves—their vowels, consonants, and rhythmic qualities—profoundly impact the meaning and interpretation of the work. These devices are not secondary effects but are integral to the poetic experience, helping to build mood, create musicality, and reinforce theme. The skillful use of sound transforms poetry from a medium that is merely read to one that is heard and felt.

3.1 The Architecture of SoundThe emphasis on sound in poetry has deep historical roots. In ancient oral traditions, before the widespread availability of written texts, devices like alliteration, assonance, and rhyme were essential mnemonic aids, helping bards and storytellers to remember and transmit long epic poems and cultural narratives. During the Renaissance and Romantic periods, the function of these devices expanded to become tools for exploring complex emotions and the beauty of the natural world.

This evolution continues into the present day. In contemporary poetry, sound remains a vital component, finding its most potent expression in the realms of spoken word and performance poetry. In these forms, the poem's life on the stage—its rhythm, cadence, and vocal delivery—is paramount, bringing the art form full circle back to its oral origins. Contemporary poets use sound to reflect a vast range of personal experiences and cultural diversities, making the auditory landscape of modern poetry richer and more varied than ever before.

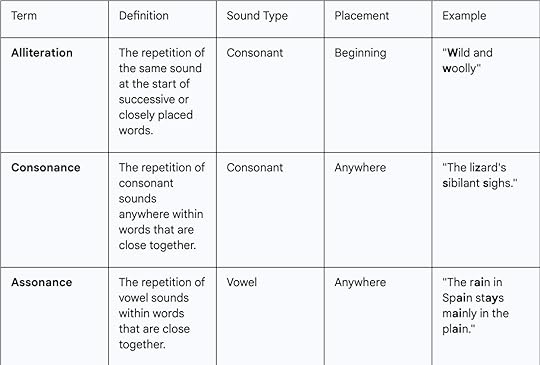

3.2 The Consonantal and Vocalic PalettesThe most fundamental sound devices can be organized by the types of sounds they repeat: consonants and vowels. The three primary devices in this category—alliteration, consonance, and assonance—are often confused, yet they create distinct effects. A clear understanding of their differences is essential for precise literary analysis.

Table 1: A Comparative Glossary of Sound DevicesTo provide immediate clarity, the following table delineates the key distinctions between these core devices. This visual guide clarifies the sound type (consonant vs. vowel) and the placement of the sound within the word (initial vs. internal), resolving a common point of confusion for students and writers.

3.3 Alliteration and Consonance in Practice

3.3 Alliteration and Consonance in PracticeAlliteration, the repetition of initial consonant sounds, has a long and storied history in English verse, serving as a key structural feature of Old English poetry like Beowulf. In later poetry, its function became more varied. In Edgar Allan Poe's "The Bells," alliteration is used for pure musicality, with the repetition of "b" and "s" sounds mimicking the merry chiming of silver bells: "What a world of merriment their melody foretells!". In contrast, T.S. Eliot employs alliteration in "The Waste Land" to a very different effect. The repetition of sibilant "s" and "sh" sounds contributes to a "sense of disjointedness and fragmentation," sonically reinforcing the poem's theme of a broken, sterile modern world.36

Consonance, the repetition of consonant sounds anywhere within words, offers a more subtle but equally powerful tool. It tends to create a "harder, more percussive sound" than the liquid flow of assonance. In Samuel Taylor Coleridge's "The Rime of the Ancient Mariner," the line "The fair breeze blew, the white foam flew, / The furrow followed free" uses both alliteration and consonance to create a driving, musical rhythm that mirrors the ship's swift movement. Sylvia Plath uses consonance to create a sense of urgency and intensity in "Tulips," where the repeated "t" and "l" sounds in "The tulips are too excitable, it is winter here" add a sharp, almost nervous quality to the line.

3.4 Assonance and the Shaping of MoodAssonance, the repetition of vowel sounds, is uniquely adept at shaping a poem's internal atmosphere or mood. Because different vowel sounds require different mouth shapes to produce, they can evoke distinct emotional and physical sensations in the reader. Soft, long vowel sounds like 'o' or 'oo' can create a soothing, calm, or somber effect, as in the line "The gentle lapping of the waves on the shore".

Conversely, harsh, short, or sharp vowel sounds like 'i' or 'e' can create a sense of tension, urgency, or distress, as in "The bitter cry of the raven in the darkness". Edgar Allan Poe, a master of sonic effects, uses assonance in "The Raven" to create a haunting and melancholic mood: "And the silken, sad, uncertain rustling of each purple curtain". The repeated short 'i' sound creates a sense of unease, while the mournful 'u' sound deepens the atmosphere of gloom and mystery.

3.5 Insight: Sound as Thematic EnactmentA sophisticated analysis of sound devices reveals that they do not merely support or decorate a theme; they can, in fact, enact it. The sonic structure of a poem can become a metaphor for its subject matter, allowing the reader to experience the theme on an auditory and visceral level. The way a poem sounds can tell its story just as powerfully as the words' literal meanings.

This principle is nowhere more evident than in Gwendolyn Brooks's iconic poem "We Real Cool." The poem's meaning is inextricably linked to its performance. The rebellious swagger of the "Seven at the Golden Shovel" is not just described; it is sonically constructed. The poem's clipped, monosyllabic words, the defiant enjambment that isolates the pronoun "We" at the end of each line, and the insistent internal rhymes ("Lurk late," "Strike straight," "Sing sin," "Thin gin," "Jazz June") all combine to create a percussive, jazzy rhythm. This sound is their "coolness." The poem's musicality embodies their carefree, rebellious lifestyle. This established sonic pattern makes the poem's conclusion all the more devastating. The final line, "Die soon," breaks the pattern. It is abrupt, unrhymed, and tonally flat. The music stops. This sonic rupture perfectly enacts the poem's theme: the seductive but ultimately fatal trajectory of the characters' lives is mirrored in the creation and subsequent shattering of the poem's musical structure.

3.6 Case Study: The Fatal Music of Gwendolyn Brooks's "We Real Cool"A detailed reading of "We Real Cool" confirms how sound enacts theme. The poem's subtitle, "The Pool Players. / Seven at the Golden Shovel," sets the scene. The voice is collective, defiant, and proud.

We real cool. We

Left school. We

Lurk late. We

Strike straight. We

Sing sin. We

Thin gin. We

Jazz June. We

Die soon.

The heavy use of assonance and consonance within the short, punchy phrases creates a series of internal rhymes that drive the poem forward with a confident beat. "Lurk late" and "Strike straight" are linked by both sound and a sense of aggressive action. "Sing sin" and "Thin gin" pair rebellion with consumption. "Jazz June" evokes a life lived for fleeting, seasonal pleasure. The placement of "We" at the end of each line (except the last) acts as a syncopated beat, a constant reassertion of their collective identity and defiance against the rhythm of a conventional sentence. This enjambment forces a pause, making the "We" an emphatic, almost boastful, declaration.

The poem's entire sonic world comes to an abrupt halt with the final two words. "Die soon" shares no rhyme with the preceding lines. Its rhythm is flat and final. The confident, musical swagger that Brooks so masterfully builds is extinguished in an instant, demonstrating with brutal sonic efficiency the tragic consequence of the life the poem describes. The sound, or lack thereof, delivers the poem's powerful, cautionary message.

3.7 The Full Orchestra: Euphony, Cacophony, and OnomatopoeiaBeyond the repetition of specific sounds, poets also manipulate the overall soundscape of their work.

Euphony (from the Greek for "pleasant sounding") refers to the use of smooth, harmonious, and musical language to create a pleasing effect. It is achieved through a combination of soft consonants, long vowels, and flowing rhythms. In contrast,

cacophony ("unpleasant sounding") is the deliberate use of harsh, jarring, and discordant sounds to create a sense of chaos, tension, or ugliness. This is often achieved with plosive consonants (like 'b', 'd', 'k', 'p', 't') and clashing sounds. A poet might use cacophony to describe a battle scene or a moment of intense emotional turmoil, matching the sound to the sense.

Finally, onomatopoeia adds a layer of direct sonic imitation to the poem. Words like "buzz," "whack," "clang," "sizzle," and "hiss" create an auditory effect that mirrors the thing being described, making the poetic world more vivid and immediate. While often used sparingly, onomatopoeia is another vital instrument in the poet's sonic orchestra, helping to create a fully realized and multi-sensory experience for the reader.

Subscribe to get Part IV directly to your inbox next week—IV: The Measure of the Line (A Critical Look at Rhythm and Meter).

August 31, 2025

II. The Logic of Comparison: Mastering Figurative Language

Figurative language is the engine of poetic meaning, an expressive and non-literal use of words that allows poets to transcend the limitations of direct statement. It is not merely a decorative "frill and flash" but an integral component of human communication, so deeply embedded in our daily speech and thought that its absence renders expression robotic and alien. This is a poetic device I firmly believe should be included in the “normal” writing syllabi as a very basic tenet of writing in any genre. When a poet employs figurative language, they are not simply saying what they mean in a more elaborate way; they are putting meaning into what they say, creating new layers of understanding through comparison, association, and imaginative leaps. This chapter will deconstruct the logic of comparison by examining the foundational division between tropes and schemes, before providing a detailed analysis of the core comparative figures of metaphor, simile, and personification.

p.s., don’t forget to subscribe now if you haven’t yet, so you can read the next installment on Rhythm (a deep dive into the sound and musicality of poetry).

2.1 Foundations: Tropes, Schemes, Tenor, and VehicleIn classical rhetoric, figures of speech are broadly divided into two categories: tropes and schemes.

Tropes are figures that alter the fundamental meaning of words. This category includes the core comparative devices this chapter will focus on—metaphor and simile—as well as other figures like irony, hyperbole, and personification. These devices create meaning by asking the reader to understand a word or phrase not by its literal definition, but by its association with another concept.

Schemes, by contrast, are figures that manipulate the ordering and arrangement of words for rhetorical effect. Devices such as anaphora (the repetition of a phrase at the beginning of successive clauses) or chiasmus (a reversal of grammatical structures) fall into this category. While schemes are essential to a poem's rhythm and persuasive power, this chapter will focus primarily on the tropes of comparison that form the imaginative core of poetic language. (Stay tuned next week for Part 3 on Rhythm & Sound!!)

To analyze these comparative figures, it is essential to understand their two core components: the tenor and the vehicle. The tenor is the original subject being described, the thing the poet wants to illuminate. The vehicle is the object or concept being used for the comparison, the lens through which the tenor is viewed. In Robert Burns's famous simile, "O my Luve is like a red, red rose," the "Luve" (love) is the tenor, and the "red, red rose" is the vehicle. The power of the figure lies in the transfer of qualities—beauty, fragrance, passion, perhaps even thorns—from the vehicle to the tenor, creating a richer and more complex understanding of "love" than a literal description could achieve.

2.2 The Metaphoric Leap: Equation, Risk, and Psychological DepthA metaphor is a direct and assertive comparison between two unlike things, made without using connecting words like "like" or "as".6 It functions as an equation, declaring that one thing is another: "He is a lion on the battlefield". This direct equation is what makes metaphor a "touch riskier" than simile; it "demands a leap of faith on the reader's part" to accept the proposed identity between two dissimilar things. When successful, however, this risk yields a "greater payoff" in terms of imaginative and emotional impact.

The use of metaphor in poetry has ancient roots, with Aristotle in his Poetics identifying it as a key element of poetic language capable of generating new insight. Metaphors can be categorized by their structure and application:

Explicit vs. Implicit Metaphors: An explicit metaphor clearly states the comparison ("He is a lion"), while an implicit metaphor suggests it through imagery and context ("The darkness crept into his soul," implying darkness is an invasive entity).

Extended Metaphors: This type of metaphor is developed over the course of several lines or even an entire poem, creating a rich and immersive conceptual framework.

Mixed Metaphors: These combine two or more incompatible metaphors, which can create a jarring or complex effect. If used unskillfully, they can be confusing, but in the hands of a master, they can represent complex, contradictory states of being.

2.3 Insight: The Evolution of Metaphor from Rhetorical Tool to Psychological MapThe function of metaphor in poetry has evolved significantly over time. In classical and early modern poetry, metaphor often served as a rhetorical tool—a way to clarify an argument, add persuasive force, or display wit. The comparison in "He is a lion" is straightforward; its purpose is to describe the man's bravery in a vivid and economical way. However, in much modern and contemporary poetry, the function of metaphor has shifted from description to enactment. It has become a primary instrument for mapping complex and often fraught psychological states.

This evolution is evident in the way poets like Sylvia Plath deploy metaphor. She does not simply use a metaphor to describe a feeling; she creates a metaphorical landscape in which the feeling becomes an active agent. The metaphor is no longer a static comparison but a dynamic participant in a psychological drama unfolding within the poem. This shift represents a profound change in the device's application, moving it from the realm of rhetoric to the core of psychological exploration.

2.4 Case Study: The Psychological Drama of Sylvia Plath's "Tulips"Sylvia Plath's poem "Tulips" serves as a masterful case study in the modern psychological metaphor. The poem is set in a hospital room, where the speaker is recovering from a procedure. She craves a state of pure, white, empty peacefulness, a surrender of self: "I am nobody; I have nothing to do with explosions. / I have given my name and my day-clothes up to the nurses". She describes this state as a kind of freedom: "How free it is, you have no idea how free— / The peacefulness is so big it dazes you."

This desired state of numb purity is violently disrupted by the arrival of a bouquet of red tulips. The tulips become the central, extended metaphor for the intrusive, painful, and demanding vitality of life itself. They are not merely flowers; they are an aggressive force. Plath uses a combination of personification and metaphor to give them agency: "The tulips are too excitable, it is winter here." They "breathe / Lightly, through their white swaddlings, like an awful baby," a simile that links them to the responsibilities and attachments the speaker wishes to escape.

The metaphor deepens as the tulips' redness becomes a direct link to the speaker's own physical and emotional pain: "Their redness talks to my wound, it corresponds."They are a physical burden, a "dozen red lead sinkers round my neck," and a source of overwhelming sensory input that "eat my oxygen" and fill the air "like a loud noise." The poem's climax sees the tulips opening "like the mouth of some great African cat," a terrifying image of predatory life. In response, the speaker's own heart "opens and closes / Its bowl of red blooms out of sheer love of me." The metaphor has come full circle: the external force of the tulips has awakened the internal, biological force of her own body, pulling her back from the brink of nothingness into the painful, vibrant world. The poem is a battleground, and metaphor is the weapon, enacting the speaker's profound psychological conflict.

2.5 The Art of the Simile: Illumination and SurpriseA simile is a comparison between two essentially unlike things that explicitly uses a connecting word such as "like," "as," or "than."By using these connectors, a simile implicitly acknowledges that the two items being compared are not identical, but share some illuminating quality. The most effective similes are those that connect ideas or images that are not typically paired, creating originality and surprise that can capture a reader's attention and convey complex emotions in a memorable way.

Billy Collins, in his poem "Books," uses a simile to deepen our understanding of the familiar act of reading: "He moves from paragraph to paragraph / as if touring a house of endless, paneled rooms." This comparison is effective because it is both apt—reading is a form of exploration—and surprising. The vehicle of the "house of endless, paneled rooms" imbues the act of reading with a sense of vastness, architectural complexity, and quiet discovery that a literal description could not achieve.

2.6 Case Study: The Accumulative Power of Simile in Langston Hughes's "Harlem"Langston Hughes's seminal poem "Harlem" (often known by its first line, "What happens to a dream deferred?") is a masterclass in the accumulative power of the simile. The poem is structured as a series of questions, with each question proposing a different simile for the fate of a "dream deferred"—specifically, the dream of racial equality and social justice for African Americans.

What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up

like a raisin in the sun?

Or fester like a sore—

And then run?

Does it stink like rotten meat?

Or crust and sugar over—

like a syrupy sweet?

Maybe it just sags