Dimitra Fimi's Blog

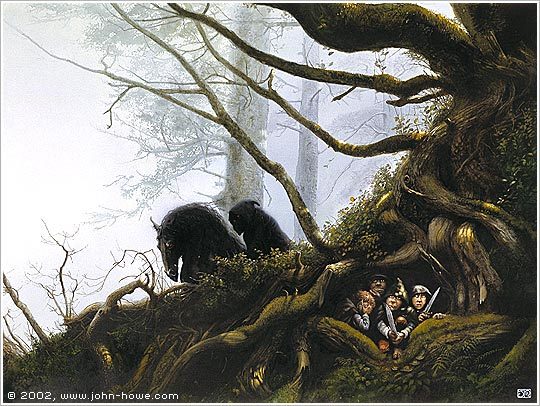

October 25, 2024

Little People inside machines: aetiologies of technology

This blog post started with one of the motifs I noticed once or twice, while researching miniature worlds and people: that of little people in the fridge – either as a permanent feature and an aetiology of the workings of a fridge, or as raiders and disruptors. The fridge, of course, is not that different to a number of other domestic spaces little people often find themselves in, but it has its particular challenges and presents its own opportunities for adventures, new characters, and a reversal of scale for everyday objects (food stuff, in this case!).

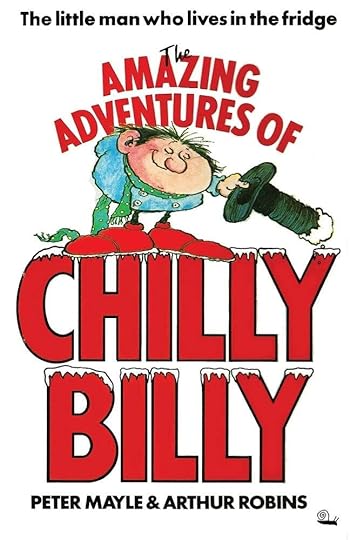

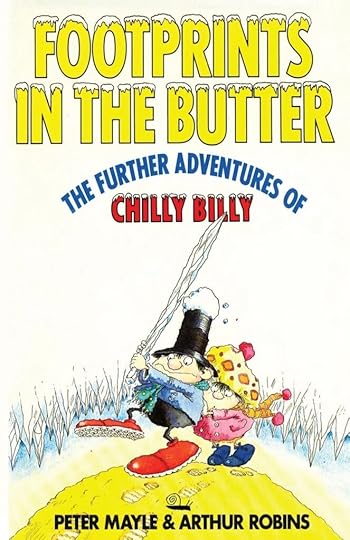

The books that first got me thinking about this are The Amazing Adventures of Chilly Billy (1980), written by Peter Mayle and illustrated by Arthur Robins, and its sequel, Footprints in the Butter: The Further Adventures of Chilly Billy (1988); as well as the first book of the Pocket Pirates series, The Great Cheese Robbery (2015), written and illustrated by Chris Mould.

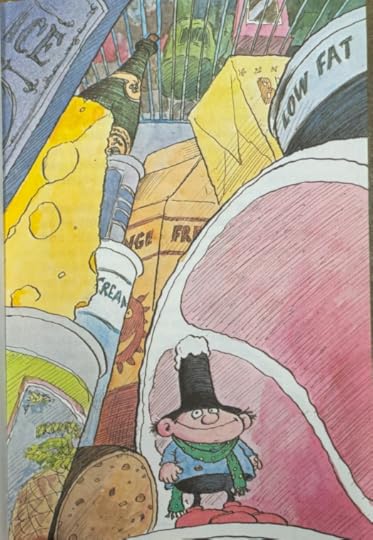

Let’s start with Chilly Billy, the “little tiny man… who lives inside your fridge”. As is often the case with books about tiny people, we are never given Billy’s exact dimensions, but we’re left to infer them from the way he interacts with objects of our own materiality. Only later on in the story are we told about another fridge character, the Mad Jumper, who is uncharacteristically tall: “nearly three quarters of an inch tall… And that, for a tiny man, is very, very big”. So can we infer that Billy is perhaps a third of an inch tall, or so? But, in my experience, when we start measuring these things properly, there is always slippage – can we really expect a realistic and consistent scale for a text like this? (Something I am thinking about further).

Chilly Billy in his natural environment, illustration by Arthur Robins

Chilly Billy in his natural environment, illustration by Arthur RobinsBut, regardless of size, Chilly Billy has important jobs to do: he turns on the light just as you’re about to open the fridge door, and switches it off again when you close it. He can hear you coming (he’s got remarkable ears and hearing capacity!) but he’s too quick – you will never see him! Still, you’d better not make fun of him, because he’ll hear and “he’ll get cross”: “And he’ll let the ice cream melt, or knock over your chocolate drink, or stamp around in the butter” (aetiologies for all sorts of in-fridge mishaps). But, of course, our story narrator has managed to catch Chilly Billy napping, so that’s how he knows and can now tell us all about him and the big secret inside our fridges. When Chilly Billy introduces himself to the narrator he explains his job:

“Billy’s the name”, he said. “Chilly Billy. I take care of your fridge – cleaning, defrosting, that kind of thing. And I specialise in turning the light on and off… I repaired a leak in the yoghurt carton. I tidied up the freezer compartment, which you left in a dreadful mess. I polished all the ice cubes. I put the top back on the milk bottle. I cleaned all the shelves.”

Chilly Billy does sound like a very useful kind of fellow! I wish someone could clean my fridge shelves! (Though, what exactly is the utility of polishing ice cubes?) Billy leaves in the freezer compartment, in a private space reached via a secret door in the back. Billy wears “suction boots” so that he can walk around the fridge, “up walls, over lemonade bottles… even… upside down, hanging from the ceiling”. (The idea of suction boots is not new, of course: Roald Dahl’s own tiny people, the Minpins, who live on trees, also wear suction boots. I think this links such creatures with the natural suction cups/mechanisms used by many small organisms in nature: frogs, bats, geckos, insects, arachnids, etc. But that’s a blog post for another day!)

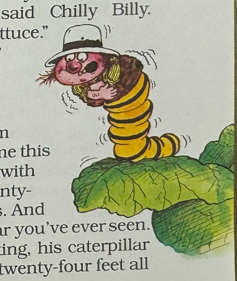

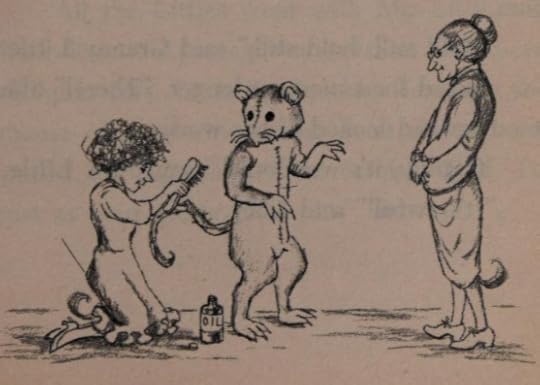

Norman the stripped caterpillar, illustration by Arthur Robins

Norman the stripped caterpillar, illustration by Arthur RobinsAfter the “aetiology” part of the narrative (Billy’s role in something we take for granted as mechanical/automatic), we hear more of Billy’s adventures. and the other creatures he meets and interacts with. These include Stripy Norman, the caterpillar, who’s found his way into the fridge accidentally inside a lettuce, who ends up being rescued, wearing one of Billy’s scarves (which leads to another potential aetiology – see if you can spot a caterpillar with a scarf on in your garden!).

Chilly Billy and Lily (rhyming names, though “Lily” also brings to mind “Lilliputians”, etc? (illustration by Arthur Robins)

Chilly Billy and Lily (rhyming names, though “Lily” also brings to mind “Lilliputians”, etc? (illustration by Arthur Robins)We also hear of Lily the nurse, who is sent in to help Billy when he feels unwell and he contacts the “I.C.E. (In Case of Emergencies) wavelentgh” on his walkie talkie. Lily diagnoses Billy with a “a nasty Warm” (because, of course he can’t have a Cold!) and dispenses medicines and advice. She ends up staying with him as they become romantically involved.

Tossing the Carrot, illustration by Arthur Robins

Tossing the Carrot, illustration by Arthur Robins And we read about the “Fridge Olympics and Frozen Sports”, which bring many more fridge people into Billy’s fridge to compete in ski-runs in the freezer compartment, ski-jump, Tossing the Carrot, and, of course, the “Great Cross-Refrigerator Race” (the sign for the contestants to be off is popping a Rice Krispie!) At the end of the book, we are offered a scene of multiple characters reunited for Billy’s birthday party (the table is a peanut butter lid, covered with a cloth, and the company sit on a large carrot, chopped up), and there is even an appendix with Billy’s favourite foods, complete with recipes! (e.g. coconut snow, chocolate chip yoghurt, etc.)

The sequel book, Footprints in the Butter: The Further Adventures of Chilly Billy, begins with the eponymous footprints all over the butter, and is more tightly focused on one adventure: saving a ladybird who’s frozen all over. Some of the characters from the previous book reoccur (Lily, Norman, the Big Jumper), but we also have Orville the Very Fat Beetle, who is instrumental in de-frosting Spotty the old ladybird. Again, as per usual with stories involving tiny people, other creatures of comparative size tend to accumulate around them: insects, often mice, etc. Two more common “little people” motifs that this second book includes, are:

The danger of falling down the sink or drains (Spotty manages to avoid this, but we see it in the adventures of Stuart Little, or the Borrowers)the desire to fly: Billy and Lily are given a ride and taste flight on Spotty’s back, something very common in such stories (for some examples see one of my previous blog posts here) Illustration by Chris Mould

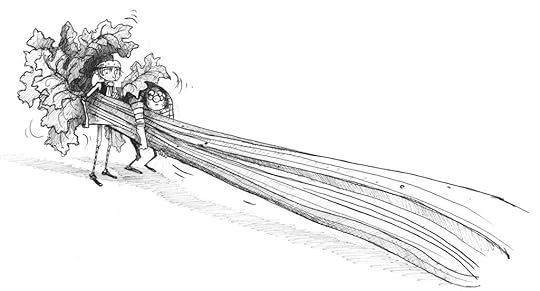

Illustration by Chris MouldThe idea of “footprints on the butter” seems to be particularly attractive, as this is an incident we also see in The Great Cheese Robbery, the first Pocket Pirates adventure. The Pocket Pirates are not fridge people – they are just miniature people that live inside a pirate ship in a bottle. We don’t get much of an explanation of their existence – there is no aetiology here, just the fun of seeing very small people surviving a human environment. In this first adventure, the Pocket Pirates, Button, Lily, the Captain, and Uncle Noggin, have to venture into “the frozen land of Fridge” to obtain some cheese for the mice, as a ransom for their miniature cat, which the (life-sized) mice have captured. In the event, Button and Lily manage to get inside a margarine tub to gain entry into the fridge.

Illustration by Chris Mould

Illustration by Chris Mould Inside the fridge, we are offered, again, the pleasure of everyday foodstuffs used in different ways by people of a different scale. Celery is particularly useful: Button lies “in the curl of a celery stick”, the Pocket Pirates use celery leaves to wipe themselves from all the substances they had to immerse themselves in, and a “huge stick of celery” is what they end up using as a wedge into the seal of the fridge door, in order to open it and escape. There is much more to the plot of this story, of course – I am only isolating the fridge incident as a comparative to Chilly Billy above – but towards the end of The Great Cheese Robbery, the human owner of the fridge sees something strange in the margarine:

But when he got the tub of margarine, right there in the middle were the imprints of two tiny people. Arms and legs and heads.

Mr. Tooey blinked hard in disbelief and headed to the room at the back for a lie down. Maybe he was going crazy after all…

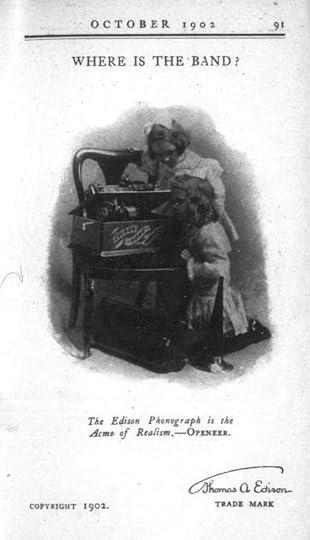

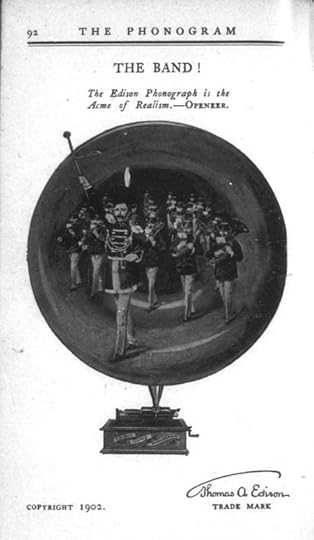

Now, the idea of little people inside the fridge, got me thinking about the wider motif (or “topos”, as Erkki Huhtamo has called it) of little people living inside different machines, and making them work – or not! Huhtamo mentions the “well-recorded popular beliefs in tiny people inside radios and TV sets” (27-8), which, evidently, goes back at least to advertising about phonographs in the 1800s, such as the examples below, which show children looking inside phonographs for the (evidently miniature) “band” inside the machine:

The Phonogram, October 1902, source (with many more examples):

Looking for the Band

at Phonographia.com

The Phonogram, October 1902, source (with many more examples):

Looking for the Band

at Phonographia.com Similarly, in his Listening to the Radio, 1920-1950, Ray Barfield shows that “[w]hen they first encountered radio in the early 1930s, some listeners had difficulty understanding its precise nature”, and mentions examples of people believing that there were tiny musicians living inside the radio, or little people doing all the talking (16-17). Radio artist Anna Friz based her “solo piece for radio transmitter and receivers, walkie-talkies, static, and voice” The Clandestine Transmissions of Pirate Jenny (you can listen to an extract here), on similar childhood beliefs and memories:

When I was young, like many children, I half-believed the voices emanating from the radio were the voices of little people who lived inside. Turn on the radio, the little people begin to talk; change the station, and they change their voices. I imagined the radio to contain a miniature theater in which the people performed whenever I wanted. (Friz 2008: 141)

In addition, the website “I Used to Believe: The Childhood Beliefs Site” lists numerous such examples, including “People on TV shows live inside the television” and “Traffic lights are operated by creatures who live inside them“.

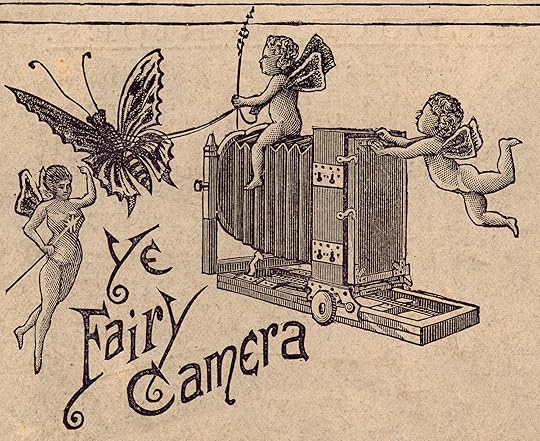

Fairy Camera, Anthony’s Photographic Bulletin, Vol. 19, No. 4, February 25, 1888, back cover, on https://www.piercevaubel.com/*

Fairy Camera, Anthony’s Photographic Bulletin, Vol. 19, No. 4, February 25, 1888, back cover, on https://www.piercevaubel.com/*All of these motifs of little people inside phonographs, radios, TV sets, or traffic lights, are largely aetiological narratives (or myths – if we want to go down that route). They offer a supernatural explanation about why and how machines work, by using creatures that may well spring out of older and more traditional beliefs. Huhtamo reminds us how fairies became entangled with early photography and cameras (see the example of an advertisement for a “Fairy Camera” on the left, which of course brings to mind immediately the Cottingley Fairies incident), but also microscopes (Laura Forsberg has discussed Fitz-James O’Brien’s short story “The Diamond Lens”, among a wider exploration of fairies and microscopy). However, in both these examples, the camera or microscope are more about the ability to see fairies, rather than fairies making them work. In most of the children’s fantasy examples I’ve found, when little people live inside machines, they are not fairies (in the traditional sense), only reduced versions of humanity, with technological accoutrements (such as suction boots) to help them navigate their environment.

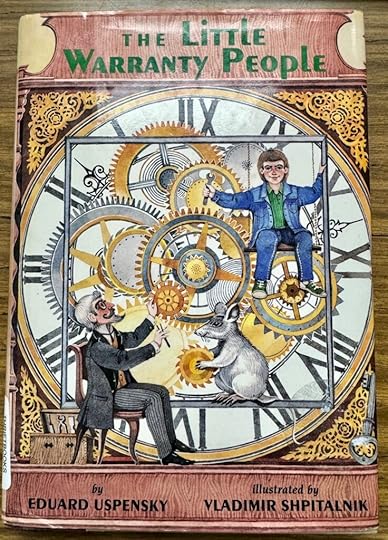

One last example I wanted to mention briefly, is another interesting aetiology, in which the little people live inside machines not to make them work indefinitely, but for a limited amount of time: The Little Warranty People, by Eduard Uspenski is a 1989 book, originally written in Russian. As per the blurb on the inside flap of the book’s dustjacket:

It’s true – the factory sends out tiny people to keep new appliances running smoothly for as long as they’re under warranty. But sometimes the little warranty people find adventures that have nothing to do with their appliances.

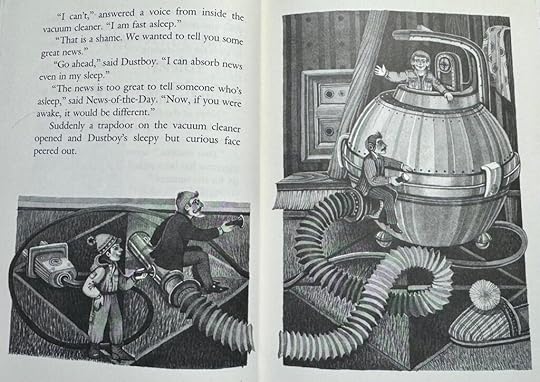

Illustration by Vladimir Shpitalnik

Illustration by Vladimir ShpitalnikThere is something both funny and pessimistic in this adaptation of the earlier idea/belief/folklore of little people inside machines, customised for a world in which machines and appliances are just not built well enough to last! The moment the warranty expires, the cast of little people we meet, Coldman (the fridge man), News-of-the-Day (the stereo man), Dustboy (the vacuum cleaner man), Carcare (the car motor man), etc. stop maintaining the machine/appliance they look after, and – we assume – the downwards spiral of wear and degradation is allowed to begin. The one (ironic) exception, is Ivan Ivanovich Burée, who lives and maintains a large antique clock, and is not going anywhere:

“…How about you? [asked Coldman] How long are you staying here?”

“For life, I’m afraid.”

“For life? Your clock has such a long warranty?” asked the surprised guest.

“No, it’s your usual warranty. It’s just that the factory where this closk was made doesn’t exist anymore. There is nowhere for me to go. I have lived here almost sixty years now. And the clock, if I say so myself, is like new. It keeps time to the second.” (p. 7).

An allegory for the much-repeated aphorism that older things used to last, while new things are made to be disposable? Perhaps, but the Kirkus Review is also pointing to this book as a “tongue-in-cheek poke at Russian politics” more specifically, so I need to think about this more!

REFERENCES

Barfield, Ray. 1996. Listening to Radio, 1920-1950. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Friz, Anna. 2008. “Re-Enchanting Radio“, Cinema Journal, 48:1, pp. 138-146.

Forsberg, Laura. 2015. “Nature’s Invisibilia: The Victorian Microscope and the Miniature Fairy”, Victorian Studies, 57:4, pp. 638-666.

Huhtamo, Erkki. “Dismantling the Fairy Engine: Media Archaeology as Topos Study,” in: Media Archaeology: Approaches, Applications and Implications, ed. Erkki Huhtamo and Jussi Parikka (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), 27-47.

*Many thanks to @DrBeachcombing for alerting me to this image!

June 2, 2024

Tolkien and the W.P. Ker Lecture at Glasgow

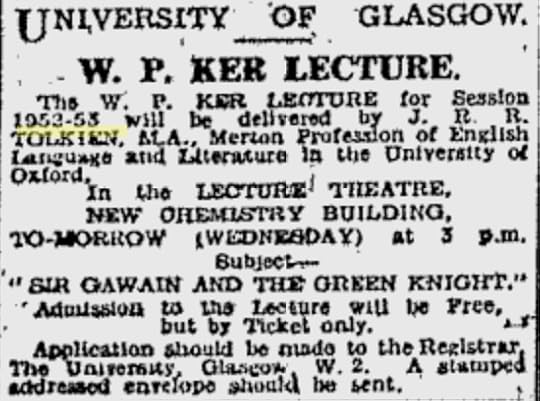

Clipping from The Evening Times (later Glasgow Times) from 14 April 1953, advertising Tolkien’s W.P. Ker Lecture the following day.

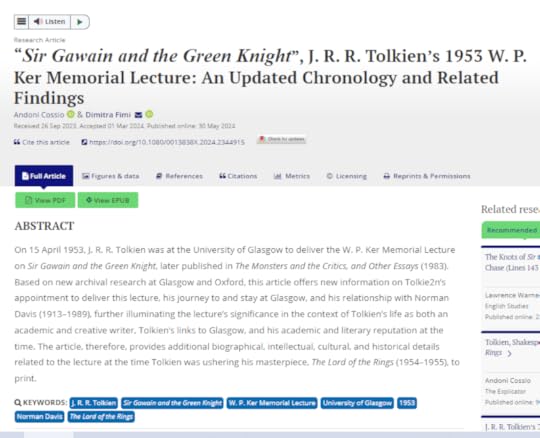

Clipping from The Evening Times (later Glasgow Times) from 14 April 1953, advertising Tolkien’s W.P. Ker Lecture the following day.Last year we celebrated the 70th anniversary of Tolkien’s W.P. Ker Lecture on Sir Gawan and the Green Knight at the University of Glasgow, which he delivered on 15 April 1953. The essay was published posthumously, in 1983, in The Monsters and the Critics and Other Essays, edited by Christopher Tolkien. After research at the University of Glasgow Archives and Special Collections, as well as within the Tolkien Papers at the Bodleian, contemporary newspapers, and other archives, Dr Andoni Cossio and I gathered new material on Tolkien’s lecture, his travel to and stay in Glasgow, and his relationship with the University, as well as his colleague (then a professor at Glasgow), Norman Davis. All of this new information can now be read in a newly published article for English Studies (a journal Tolkien himself had published in in, with Simonne d’Ardenne![i]) and is available open access here.

Looking into the history of the W.P. Ker Lectureship, though, has brought a few more interesting revelations, which I am sharing here.

First of all, who was W.P. Ker?

William Paton Ker (1855–1923) was a University of Glasgow alumnus, who then went on to hold academic positions at the University of Oxford, University College of South Wales, and University College, London. The legacy of the Glasgow writer John Brown Douglas provided funds to establish the W. P. Ker Memorial Lecture in 1938 in commemoration of W.P. Ker. The patron was the University Court, and “the foundation originally provided for an annual lecture on some branch of literary or linguistic studies”[ii].

The full list of W.P. Ker Memorial Lecturers shows us that a number of Inklings (or Inklings-adjacent people) delivered this talk, alongside other interesting personalities with connections to Tolkien. Here’s the list, with a few significant names highlighted:

1939 Raymond Wilson Chambers, MA, DLitt, FBA: Professor of English Language and Literature in the University of London1940 William Macneile Dixon, MA, LittD, LLD: Emeritus Professor of English Language and Literature1941 Thomas Stearns Eliot, MA, LittD, LLD: Honorary Fellow of Magdalene College, Cambridge1943 Lord David Cecil, MA: Fellow of New College, Oxford1944 Edward Morgan Forster, LLD: previously Fellow of King’s College, Cambridge1945 Charles Langbridge Morgan, MA: author1946 Edwin Muir: author1947 Helen Waddell, MA, DLitt, LLD: scholar and author1948 Harold George Nicolson, CMG: author1949 Roger Aubrey Baskerville Mynors, MA, FBA: Kennedy Professor of Latin in the University of Cambridge1950 Sir William Craigie, MA, LLD, DLitt, FBA: Professor Emeritus of English, University of Chicago1951 Geoffrey Langdale Bickersteth, MA: Professor of English Literature in the University of Aberdeen1952 Sydney Castle Roberts, MA: Master of Pembroke College, Cambridge1953 John Ronald Reuel Tolkien, MA: Merton Professor of English Language and Literature in the University of Oxford1954 Sigurdur Nordal: Minister at Copenhagen1955 Benjamin Ifor Evans, MA, DLitt: Provost of University College, London1956 Geoffrey Winthrop Young, MA, DLitt1957 Wystan Hugh Auden, MA: Professor of Poetry in the University of Oxford1959 Clive Staples Lewis, MA, D-ès-L, DD, FBA: Professor of Mediaeval and Renaissance English in the University of Cambridge1961 James Runcieman Sutherland, MA, BLitt, LLD, FBA: Lord Northcliffe Professor of Modern English Literature in University College, London1965 Cleanth Brooks, BA, BLitt: Professor of English in Yale University1968 Gwyn Jones, CBE, MA: Professor of English at the University College of South Wales and Monmouthshire1970 Eyvind Fjell Halvorsen, DoctPhilos: Professor of Norse Philology in the University of Oslo1972 John Frank Kermode, MA: Lord Northcliffe Professor of Modern English Literature in University College, London1974 Denis Donoghue, MA, PhD: Professor of Modern English and American Literature in University College, Dublin1976 E Peter M Dronke, MA: University of Cambridge1979 Francis Berry, MA: Department of English at Royal Holloway College, University of London1981 Ian Dalrymple Mcfarlane, MBE, MA, DUParis, FBA: University of Oxford1983 William Lobov: University of Pennsylvania1986 George Steiner, MA, DPhil1995 Lee Paterson: Yale UniversityR.W. Chambers was an appropriate choice for the very first W.P. Ker Memorial Lecture, since he succeeded W.P. Ker as Quain Professor of English Language and Literature at UCL. Chambers also famously declined to accept the Rawlinson and Bosworth Professorship of Anglo-Saxon at Oxford, and so the post went instead to Tolkien. Chambers and Tolkien knew and admired each other’s work, especially on the Old English epic poem Beowulf. You can see a letter from Tolkien to Chambers here.

Lord David Cecil was an Oxford academic, working as a historian and biographer, who often attended meetings of the Inklings.

Sir William Craigie was a philologist. Tolkien succeeded him as Rawlinson and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon when Craigie resigned to join the University of Chicago (where he still was when he delivered the W.P. Ker Memorial Lecture).

W.H. Auden was, of course, a celebrated poet who – at the point of delivering the W.P. Ker Lecture – had just been appointed Professor of Poetry at Oxford. He attended some of Tolkien’s lectures when a student in Oxford, and the two later became friends and corresponded regularly. Auden also praised highly The Lord of the Rings in his review.

C.S. Lewis, well, needs no introduction, really! He was the epicentre around whom the Inklings gathered, and one of Tolkien’s best friends, and, perhaps most importantly, someone who encouraged Tolkien to finish (some of!) his work!

Gwyn Jones was a scholar and writer who founded The Welsh Review, in which Tolkien’s The Lay of Aotrou and Itroun was first published in 1945.

A few more interesting names that crop up in this list (no Tolkien connections this time!):

T.S. Eliot – the Nobel-prize-winning poet (1941 W.P. Ker Lecture)E.M. Forster – novelist (1944 W.P. Ker Lecture)[iii]Edwin Muir – Scottish poet and novelist (1946 W.P. Ker Lecture)The W.P. Ker Lectureship seems to have attracted some of the most illustrious minds of its time, from academics to creative writers. I am grateful to Michael Moss, Moira Rankin and Lesley Richmond who compiled the book Who, Where and When: The History & Constitution of the University of Glasgow, which gives the full list of the W.P. Ker lecturers as reproduced above.

On 27 April 2023, the Centre for Fantasy and the Fantastic at the University of Glasgow held an event to celebrate the 70th anniversary of Tolkien’s W.P. Ker Memorial Lecture on Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. You can watch it here:

NOTES

[i] “‘iþþlen’ in Sawles Warde”. English Studies, vol. 28, issue 1-6, 1947, pp. 168-170. https://doi.org/10.1080/00138384708596789

[ii] Moss, Michael, Moira Rankin, and Lesley Richmond. Who, Where and When: The History & Constitution of the University of Glasgow. Glasgow: University of Glasgow, 2001. https://www.gla.ac.uk/media/Media_61834_smxx.pdf

[iii] Well, there is a sort of Tolkien connection here: Tolkien nominated Forster for the Nobel Prize in 1954. Dennis Wilson Wise has written on Tolkien’s possible reasons for this nomination – see here: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol36/iss1/9/. Forster was nominated for the Nobel Prize many times but never won.

April 22, 2024

Venturing Out: The Littles Take a Trip

This is the second blog bost in a series about John Peterson’s The Littles books (1967-2002), you can find the first one here.

The second book, The Littles Take a Trip, was published in 1968. It follows the Littles as they venture out of the Biggs’ house and in search of other people like them. This is another theme I’ve encountered time and time again in miniature fantasies: the “last of their people” narrative, in which the little people think they’re the only ones of their kind (left) and go on a trip to find others. Often it’s the children of the little people who long for that sense of community and an escape from social isolation – parents or other grown-ups tend to be more risk-averse or set in their ways.

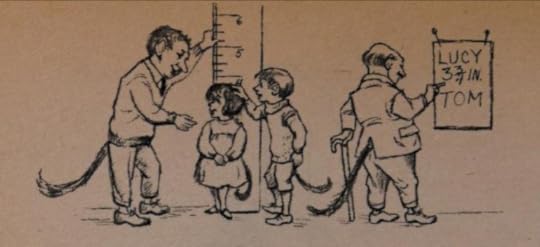

Various covers of The Littles Take a Trip (1968)

Various covers of The Littles Take a Trip (1968)As is often the case with children’s books, the second book in the series recaps what the reader should know from the first book, but also embelishes this knowledge a little. In the very first chapter of The Littles Take a Trip we get a reminder of the Littles’ physique (they are small, they live in the walls of the Biggs’ house, they have tails), but we get this significant added comment: “They weren’t midgets or dwarfs or even elves. They were tinier than that” (Peterson 1968, p. 6). This is interesting for all sorts of reasons.

First, “midgets” and “dwarves” are terms related to physical stature and physique, as affected by genetic or medical conditions causing dwarfism – both terms are often considered derogatory nowadays. I wonder why the text needs to make these comparisons when it’s already given measurements for the Littles (6 inches for Mr Little, and shorter than that for other members of the family). Clearly, these are not realistic mesurements, even for human beings who are affected by dwarfism. Is there perhaps an implication that young children reading the books won’t have a sense of scale?

Having said that, the third comparative does not fit with the first two: there is no standardised measurements for elves, so that the Littles were “tinier than that” doesn’t quite work. But, then, the idea that little people in children’s fantasies may be mistaken for creatures of folklore, such as fairies, or elves, or gnomes, is not unusual – as, for example, in The Borrowers, in which Arietty contends that the borrowers are as divided as humans in believeing or not believing in fairies (she is, of course, herself, nothing of the sort, as she insists). But, on the other hand, some of the little people in children’s fantasies are indeed creatures of folklore: e.g. the gnomes in B.B.’s The Little Grey Men, or in Upton Sinclair’s The Gnonobile. So, as with the comparison of little people with mice I discussed in my last blog post, their relation to fairies, elves, etc. is equally slippery and unclear (or at least questioned) a lot of the time.

The other thing that is emphatically repeated at the opening of the book is that the Littles are “people” – just smaller versions of humanity, one assumes (but for those troublesome tails…). Tom and Lucy, the two children of the Little family, watch longingly Henry Bigg having a party and have this exchange:

As Tom and Lucy watched Henry Bigg and his friends, Lucy said, “They look silly without tails.” She started

(Peterson, 1968, p. 7)

giggling and couldn’t stop.

“Be quiet!” said Tom Little. “They might hear you.”

“I can’t help it,” said Lucy. She held her hand over her mouth.

“Besides, it’s not important,” said Tom. “Their not having tails, I mean.”

“If it’s not important, then why do we have them?” said Lucy.

“Because we do, that’s all,” said Tom. “We’re the same as they are, only smaller. People are people.”

So the Littles are just human beings in miniature, tail or no tail, and indeed Tom’s words echo the famous catch phrase from an earlier book about tiny people, Dr Seuss’s Horton Hears a Who! (1954): “A person’s a person, no matter how small”. The ethics of assigning value to tiny lives is another perennial theme in miniature fantasies.

But of course Lucy notes another big difference between humans and the Littles, which becomes the “inciting incident” of this story: that human children like Henry Bigg can have parties and lots of children to play with, whilst the Little children are isolated, the two siblings only having each other. And that’s where the text reveals that there are many more “tiny people” with tails, at least in the immediate area, but that survival and safety rules have established the custom of only one family per human household. The other tiny families also have appropriate names:

Tiny families like the Littles, the Fines, the Smalls, the Crums, the Shorts, the Buttons, and all their kith and kin, lived

(Ibid., p. 17)

all over the Big Valley. But they never got together.

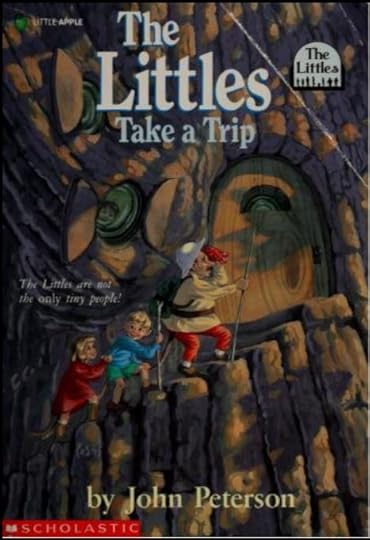

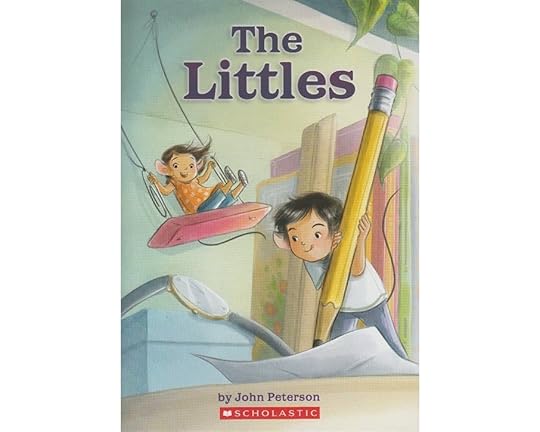

Illustration for The Littles Take a Trip (1968), by Roberta Carter Clark

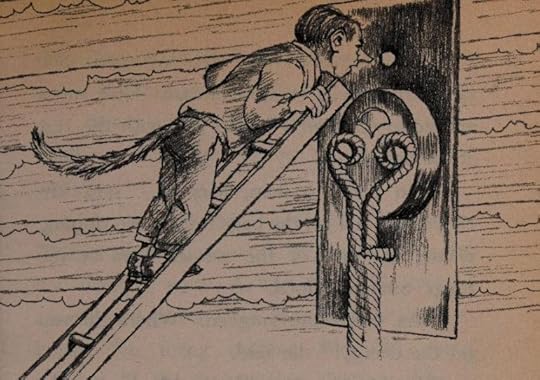

Illustration for The Littles Take a Trip (1968), by Roberta Carter Clark This leads to the introduction of a new character, Cousin Dinky, a daring adventurer, “the only person in the Big Valley to travel from house to house” (ibid., p. 17), delivering letters and messages for tiny grown-ups and children alike (apparently Lucy Little has a pen-friend in Tina Small). Cousin Dinky travels by means of his glider, which he has built himself.

A bit of a parenthesis here, well, a parenthetical paragraph: I think the text misses a trick not to give us any details on the materials Dinky used or how he learned to build a glider. The idea of little people flying is actually not that unusual in children’s miniature fantasies: the borrowers, when trapped in an attic in The Borrowers Aloft, build a balloon (by finding instructions in the Illustrated London News) and we are given details on the (everyday, small, human) materials they use, as well as how they solve various engineering problems. Earlier than Mary Norton’s series, in T.H. White’s Mistress Masham’s Repose, Maria becomes obsessed with seeing the Lilliputians fly in a cheap airplane model, modified by further accoutruemnts (once more based on diagrams in the Illustrated London News) but things go (nearly fatally) wrong and the idea is abandoned. Other little people fly on birds (e.g. in Roald Dahl’s The Minpins), notably geese (e.g. in Selma Lagerlöf’s The Wonderful Adventures of Nils, and – I think in direct hommage to the former – in Terry Pratchett’s Nome trilogy).

Illustration for The Littles Take a Trip (1968), by Roberta Carter Clark

Illustration for The Littles Take a Trip (1968), by Roberta Carter Clark As the Littles eventually venture outdoors for a grand meeting of tiny people and their families at the house of the Smalls, they realise how hard it is to navigate a natural environment, rather than the domestic, man-made space they’re used to (we see this in The Borrowers Afield too, and in the subsequent Borrowers books). They are attacked by both sparrowhawks and later on a weasel, and they are impeded by the size of natural obstacles:

The walking was rough. They had to go around weeds and thick, wild bushes. It took a long time to go a short way. […]

It was tough going. They had to climb over pebbles and twigs. The thick grasses were over their heads. Uncle Pete almost got trapped in a mudhole filled with wet, rotting leaves.

(Ibid., pp. 63, 65)

Illustration for The Littles Take a Trip (1968), by Roberta Carter Clark

Illustration for The Littles Take a Trip (1968), by Roberta Carter Clark However, not all tiny people are that ill-suited to the (much bigger elements of the) natural environment. When the Littles are confronted by a skunk, they soon realise that another one of their kin rides on the animal, and has tamed it: Stubby Speck! We are told that Mr Speck and his family live in a tree in the woods, rather than a human house, and he calls the Littles “House Tinies” (ibid., p. 70), introducing for the first time the term “Tinies” for the “species”(?) the Littles belong too, and sub-diving this into further smaller caregories: House Tinies vs. Tree Tinies (later books introduce more such sub-categories). He notes that the Littles don’t look different to him and his family, but: “You do talk kinda different, though” (ibid.). The Specks’ house is described as follows:

The Stubby Speck family lived in the lowest branch of a giant oak tree. Steps had been cut into the bark of the great tree. They went around and around the trunk until they came to the lowest branch. The stairway looked like part of the tree. The Littles did not even see the stairs until Mr. Speck pointed them out. […]

Tom pointed to the lowest branch. “What’s that?” he said. “What are those round shiny things in the tree?”

(Ibid., pp. 73-4)

“They’re my windows, son,” said Mr. Speck. “I made them myself from the bottoms of bottles that floated into the woods on the brook.”

“Wonderful!” said Mr. Little.

Mr. Speck spoke again, “The bark shutters are made so they’ll swing shut to hide the windows,” he said. “Sometimes Henry Bigg and his friends climb on our tree. When they do, we just shut everything up tight and wait for the boys to go away.”

Laer, the Littles and the Specks had lunch in the largest room in the tree. Sunlight streamed through the colored bottle windows. A long oak table grew right out of the floor. It was part of the living tree.

What we have here, therefore, is the equivalent of a treehouse (something along the lines of the one in Swiss Family Robinson – the 1960s Disney film rather than the novel!) which combines organic elements (e.g. the table as an outgrowth of the tree) and man-made things in imitation of human material culture (the steps carved into the bark of the tree, however hidden/camouflaged; the windows made out of repurposing human rubbish; etc.). We hear later that the Specks’ ancestors initially lived in human houses (so their reproduction of human materialities makes sense) but left for the woods after two incidents of fire damage. But “house living must be getting better”, says Mr Speck (ibid., p. 80) and that brings us to another dichotomy the Specks introduce: self-sufficiency (with all its challenges) vs. dependency. The main bone of contention here is food.

Already in the first book of the series, The Littles (1967), it is made crystal-clear that the Littles “got all their food from the Biggs. When the Biggs had roast beef for dinner, the Littles had roast beef for dinner too” (Peterson 1967, p. 9). This dependency is so absolute that when the Newcombs arrive, the Littles get sick and tired of eating hamburger every day, and Mrs Little laments her lack of domestic skills:

“I suppose I should have learned to cook,” said Mrs. Little. She looked around the table. “Mrs. Bigg was such a good cook it didn’t seem necessary for me to cook too. I guess she spoiled us.

All the Littles nodded.

(Ibid., p. 22)

So, when we get to the Specks in The Littles Take a Trip, given that there are no humans to take food from, Mrs Little is quick to ask Mr Speck about the cooking arrangmeents:

“Your wife does her own cooking?” said Mrs. Little.

“She does many things well, ma’am,” said Stubby Speck, “but cooking is the jewel in her crown.”

(Ibid., pp. 71-2)

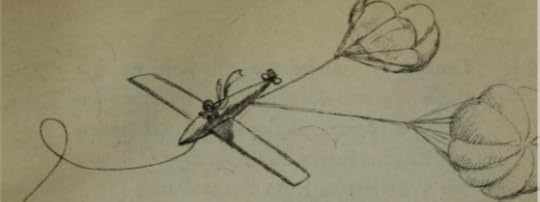

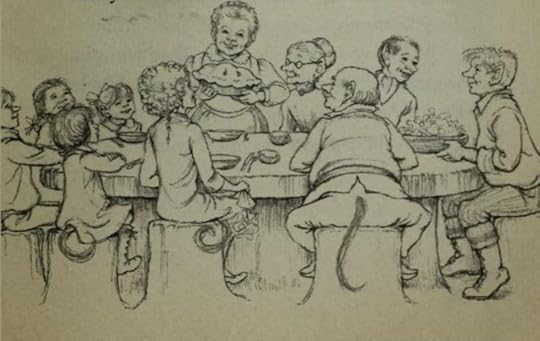

The food the Specks eat is more natural and rustic: “There was mushroom pie, dandelion green salad, sassafras tea sweetened with honey, and blackberries for dessert” (ibid., p. 75). Note also how the illustrations of the two families eating points to urban vs. rural stereotypes:

Illustration for The Littles (1967), by Roberta Carter Clark

Illustration for The Littles (1967), by Roberta Carter Clark  Illustration for The Littles Take a Trip (1968), by Roberta Carter Clark

Illustration for The Littles Take a Trip (1968), by Roberta Carter Clark The general disposition and portrayal of the Specks is more old-fashioned in an American context too. Stubby Specks wears a cowboy hat, addresses the female members of the Littles family as “ma’am” and “miss”, takes off his hat and bows to them (ibid., p. 70) and generally speaks in a slight accent (see extracts above) – though my sense of American vernaculars is not reliable to speculate more on the effect intended here (comments very much welcome!). The Specks also face a harsher life – they always have to work hard to prepare for the winter, rather than relying on the Biggs’ central heating.

After the interlude at the Specks’ house, the Littles depart again for their original destination, and after a few more adventures (notably the weasel attack briefly mentioned above), they reach their destination, the house of the Smalls, and Lucy and Tom meet lots more children of their age. The book ends with the phrase: “And so began the first annual meeting of the tiny people of the Big Valley” (ibid., p. 95), which promises an expansion of the tinies world in following books.

A few more scattered thoughts on this book:

In a exchange between Tom and Lucy we find out their fears about what humans may do if they ever discover the Littles existed: “‘Maybe they’d put us in a museum,’ said Tom, ‘or a circus… […] And maybe they’d kill us […] They might think we were some kind of animal.’ He looked at his tail.” (p. 10) – the last possibility takes us back to the ideas explored in the previous blog post on little people and mice. But being displayed (for money) or studied are fears many tiny people share in children’s fantasies (e.g. the borrowers, Pratchett’s Nomes, etc.). The ethics of discovering a new species are very much entangled with these worries.Another slightly unusual ethical dilemma this book raises are the ethics of watching/peeping: at the opening of the book Tom and Lucy bemoan their lack of friends outside their family and attribute to this lack their obsession with watching Henry Bigg and his friends. Tom says: “All we ever do is watch Henry Bigg and his friends […]. It’s creepy. We know all about Henry and his friends… and they don’t even know we’re alive” (p. 34). The wording is interesting here: “creepy” is a charged word. To make things even more problematic, Mr Little adds (addressing his wife): “They’ve been watching too much […]. We’ll have to set a time limit. It’s no good for them to watch so much. We tiny people must have lives of our own.” (ibid.). Their parents seem to consider this “watching” as something equivalent to the fear that kids watch too much TV, and live their lives through a screen.Appendix: Tiny MaterialitiesOnce more, as with the first book of the series, The Littles, I was surprised to find fewer examples of repurposing everyday small objects for different uses as featured in many miniature fantasies. Here’s the crop from this book:

In the text:

The Smalls, in anticipation of their guests, “set about making extra beds from some cigar boxes Mr. Small had been saving for years” (p. 41). Famously, Arietty’s bedroom is made out of cigar boxes.In Roberta Carter Clark’s illustrations:

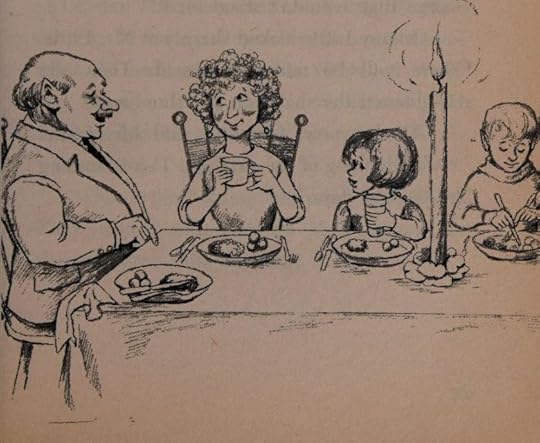

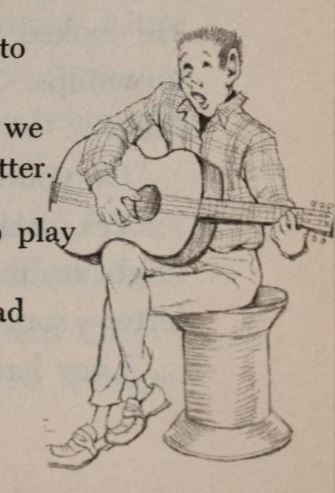

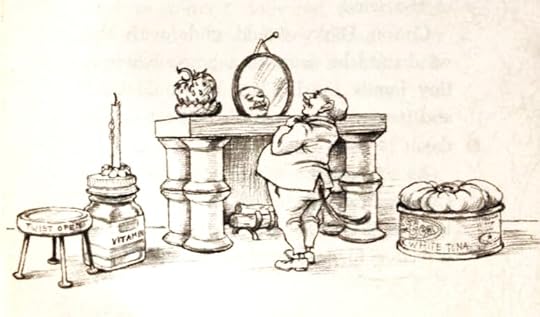

Illustration for The Littles Take a Trip (1968), by Roberta Carter Clark In the scene below in which Uncle Pete looks at the mirror, we have (from left to right): a stool made of foud nails and the cap of bottle or jar, a candle holder made out of a vitamin bottle, the fireplace made out of woodern spools, and a pouf made out of a cushion on a tuna can (p. 20). Cousin Dinky sits on a wooden spool to play his guitar (p. 33)

Illustration for The Littles Take a Trip (1968), by Roberta Carter Clark In the scene below in which Uncle Pete looks at the mirror, we have (from left to right): a stool made of foud nails and the cap of bottle or jar, a candle holder made out of a vitamin bottle, the fireplace made out of woodern spools, and a pouf made out of a cushion on a tuna can (p. 20). Cousin Dinky sits on a wooden spool to play his guitar (p. 33) Illustration for The Littles Take a Trip (1968), by Roberta Carter Clark

Illustration for The Littles Take a Trip (1968), by Roberta Carter Clark

April 14, 2024

The Littles: Of (Tiny) Men and Mice

At last I’ve managed to get my hands on The Littles series (1967-2002), by John Peterson (1924-2002) – well, at least most of the books in the series (still missing one, I think, but getting there!)

This is the first time I am reading them, so here is the first of a series of blog posts on these books, with some first thoughts and musings:

The first book in the series, published in 1967, is simply titled The Littles, and introduces the family of William T. Little (the dad), Mrs Little, Granny Little, Uncle Pete, Tom Little (10 years old) and Lucy Little (8 years old).

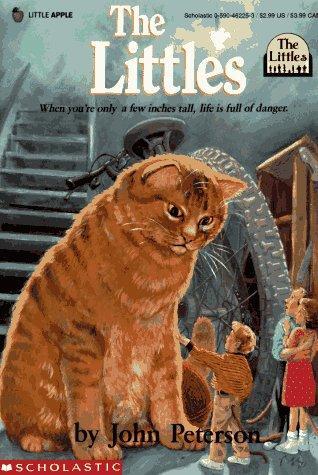

Various covers of The Littles

Various covers of The LittlesWhat the Littles are is a fuzzy thing, as is the case with many of the little people encountered in other children’s fantasies. In chapter 1, we are simply told that: “William T. Little and his family were tiny people” who “looked almost like people you see every day” apart from the fact that they are “much smaller” (Peterson, 1967, p. 7). We actually do get a measurement in the very first page of the first chapter, which is something that we don’t get, for example, for Mary Norton’s borrowers until the third book (The Borrowers Afloat, 1959). Like Pod, Mr Little is six inches tall, though, the narrator tells us, “he was big for a Little. The other Littles were even smaller” (ibid., p. 8).

Illustration for The Littles (1967), by Roberta Carter Clark

Illustration for The Littles (1967), by Roberta Carter ClarkWhat makes the Littles unlike “people” is perhaps the most memorable part of their physique:

In one way the Littles did not look at all like other people. They had tails. The Littles were proud of their tails. They kept them combed and brushed, and sometimes the women curled their tails when they wanted to look especially nice.

(Ibid., p. 8)

I have been noticing for a while how little people in miniature fantasies are very often compared to, or mistaken for, mice, and the Littles’ tails add to this parallel: so much so, that, later on in the story, Tom Little dresses up as a mouse, using a costume made by Granny, but uses “his own tail, of course” (ibid., p. 43). I shall return to the Littles and/vs, mice below.

The Littles are from the opening of the book set up in opposition to the Biggs. They live in a house owned by George W. Bigg, whose family are ignorant of the Littles’ presence. The Littles live in “tiny rooms in the walls of the house”, and “took everything they needed from the Biggs”, including food and small things that seemingly go “missing” (ibid., pp. 8-9). In contrast with the borrowers, whose ethics of “borrowing” (vs. what human beings would call “stealing”) are an interesting thread in the books, the Littles seem to have a secret transactional relationship with the Biggs, whom they pay back by mending and maintaining things in the house:

The Littles helped the Biggs in return for the things they took. Only the Biggs didn’t know it. For one thing, the Littles were good at fixing things. They ran back and forth inside the walls repairing the electric wires whenever they needed it.

(Ibid., pp. 9-10)

The Littles were good plumbers, too. On cold winter days they kept the outside water pipes from freezing. Often they had to stay up all night keeping the pipes warm by candle fire.

Mr. Bigg could never understand why his plumbing and electricity worked so well. “I can’t believe it,” he would say. “I have less trouble with this old house than my neighbors do with their brand-new houses.” He would shake his head. “I guess they don’t make houses the way they used to.”

This is an interesting concept. This unwitting quid pro quo points to a symbiotic relationship – specifically mutualism: a relationship between organisms of different species, in which both organisms benefit from the association. The fact that the Littles are in charge of some of the most tricky things householders often worry about (while lacking the expertise to fix them themselves), that is, electricity and plumbing, makes them particularly useful – it feels as if the text wants to provide a good excuse for the existence of the Littles, a use for them, something to distinguish them from, say, vermin – here’s the mouse associations again.

The word vermin points to both harmful and often parasitic organisms. As per above, the Littles’ existence isn’t that different from mice: they live in the walls of the house, they feed on crumbs, and they fit into all the nooks and crannies of a house, disappearing quickly when (if ever!) spotted. But mice, of course, are not just classed as vermin because they carry diseases, contaminate via their excretions, and chew through furniture, etc., but also because they often chew through electrical wires causing outages and/or fire hazards. In many ways, the Littles are anti-mice – clean, tidy, and fixing electrical problems.

Bearing this in mind, therefore, it’s not that surprising that the plot of this first book of The Littles series revolves around mice: the “inciting incident” is that the Biggs leave for a while on holidays, and the Newcombs arrive to rent the house during that time. Mr Newcomb is an artist and Mrs Newcomb a writer. They both plan to use their stay as artistic retreats, and make a conscious decision not to spend too much energy looking after the house (what that says about the story’s attitude to creatives is another story…):

The Newcombs were indeed bad housekeepers. Food was left around uncovered. Floors were not swept after meals. Garbage spilled out of the can. When the lid fell off, it wasn’t put back on.

(Ibid., p. 26)

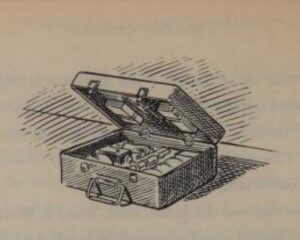

“All those crumbs! Mark my words,” Granny said, “there WILL be mice.”

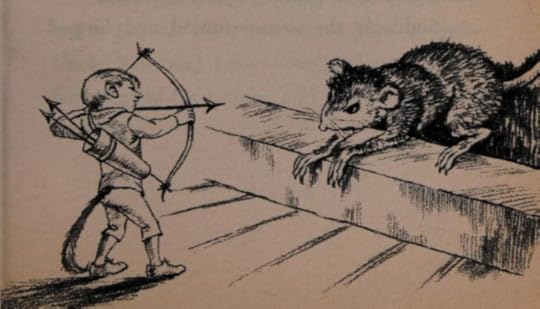

And, of course, mice do show up. The grown-ups of the Little family remember mice as old enemies. We hear of “the old days” when Uncle Pete was injured during the “Mice Invasion of ’35” (ibid., pp. 22, 28), which explains Uncle Pete’s limp, but also brings up Uncle Pete’s brother, Tim, who lost his life in that fight (or war? resonances of WWII here?). But there must have been previous “wars” with mice in the remoter past, as the Littles dig out a chest of weapons including a bow and arrow. The arrow has this inscription on it: “Made in 1825 by Chas. B. Little” (ibid., p. 29).

Illustration for The Littles (1967), by Roberta Carter Clark

Illustration for The Littles (1967), by Roberta Carter Clark There are a few skirmishes with mice, but the Littles realise that the best way to get rid of them is alert the Newcombs that they exist! But the Newcombs are so oblivious that the daring plot to dress up Tom as a mouse and parade him in the kitchen is hatched up. The plan works and the Newcombs realise the error of their ways and bring in a cat. Once more, therefore, the relationship between mice and Littles is highlighted – ironically, the Littles have to become more like mice to protect themselves (and the Biggs’ house), though, the tale-tell tails are once more making this dichotomy slippery:

“It’s the first time any of the big people have ever seen any of us,” said Mrs. Little. “And the only real part of Tom they’ll see is his tail.”

(Ibid., p. 46)

Illustration for The Littles (1967), by Roberta Carter Clark

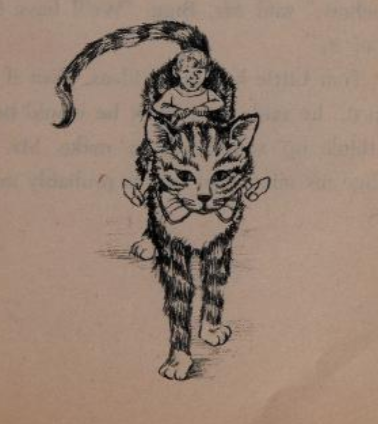

A development that the mice invasion causes is another (and very beneficial) relationship between the Littles and animals: Tom’s taming of the cat. The cat is initially seen as a new enemy (and blamed on the Newcombs and the mice), but Tom manages to control it very simply: by defying the previous generation’s fear of animals and just speaking to it:

Now Tom was standing next to the cat. He reached up and scratched her gently under the chin. The cat closed her eyes slowly and purred louder. Tom kept talking to her all the while.

(Ibid., pp. 78-9)

“It was the talking that did it,” said Mr. Little later. “The way I figure, the cat didn’t know we were people until Tom started talking to her. I guess cats like people to talk to them.”

Illustration for The Littles (1967), by Roberta Carter Clark

Illustration for The Littles (1967), by Roberta Carter Clark And this is one more distinction the text makes between mice (or any other animal) and the Littles: language, popularly understood as a unique human ability (though science has challenged this for a while now). The grown-up Littles are particularly anxious to make this point:

“Now we may be little,” said Mr. Little, “but we are men.”

(Ibid., p. 70-71)

“Of course we are,” said Uncle Pete. He looked sideways at his tail. “We’re not animals.”

That “sideways” look at the tail, though, betrays some sort of doubt, perhaps.

Appendix: Tiny MaterialitiesAnother element of miniature fantasies that interests me is the repurposing of everyday small objects for different uses when the scale of the characters is switched to the minuscule – so, a matchbox becomes a bed, an acorn cup becomes a drinking vessel, etc. I was surprised not to see much of this in the actual text of the Littles (it abounds in other miniature fantasies), but Roberta Carter Clark’s illustrations added a few examples of this phenomenon, not mentioned in the text:

Illustration for The Littles (1967), by Roberta Carter Clark

Illustration for The Littles (1967), by Roberta Carter Clark In the text:

The Littles use the electrical socket on the kitchen counter as a door to access the Biggs’ house (p. 9). They also use a hole in light switch in the hall (one of the screws is missing, apparently) as a “secret look-out place” (p. 15).The Littles have a tin-can elevator: “They had rigged up the tin-can elevator from an old soup can and bits of string tied together” (p. 46).Uncle Pete’s sword is “made from one of Mrs. Bigg’s needles” (p. 53).

In Roberta Carter Clark’s illustrations:

Granny Little is using a wooden spool as an occasional table, on which a tin soda bottle cap holds her wool (which comes from unravelling one of the Biggs’ socks!) (p. 12)Uncle Pete (holding his sword) is sitting on a match box (p. 74) Illustration for The Littles (1967), by Roberta Carter Clark

Illustration for The Littles (1967), by Roberta Carter Clark  Illustration for The Littles (1967), by Roberta Carter Clark

Illustration for The Littles (1967), by Roberta Carter Clark

December 6, 2023

Tolkien and the Fairies: Faith and Folklore

The below was presented as a paper at Oxonmoot 2010 (24th – 26th September). I include endnotes to indicate when I refer to contemporary/topical matters. Please also note that this piece was written for oral delivery, so it’s not polished in the way a piece for publication would be.

Tolkien’s essay On Fairy-Stories has been widely regarded as an important text not only for understanding Tolkien’s own mythopoeic fantasy, but also as an analytical tool for discussing fantasy literature in general. Tolkien first delivered this essay as a lecture, the Andrew Lang lecture at the University of St. Andrews in 1939, and it was published during Tolkien’s lifetime in 1947 in Essays Presented to Charles Williams, edited by C.S. Lewis, and posthumously in a number of different collections, most notably in The Monsters and the Critics, edited by Christopher Tolkien.

A number of the manuscripts of On Fairy-Stories have long been held not far from here[i], in the Western MSS collection of the Bodleian Library, and I was lucky enough to study them while doing my PhD, and to even be allowed to quote from them in my PhD thesis and the book that came from that research.

But there was a major issue that somewhat hindered my study – Tolkien’s handwriting, which ranges from the beautiful to the unreadable! John Garth has commented on this antithesis between Tolkien’s elegant scripts versus his hasty, indecipherable handwriting at times. He described the latter as: ‘a scrawl resembling nothing so much as an electro-cardiograph image of a frenzied pulse’ (Garth 2003: 13)

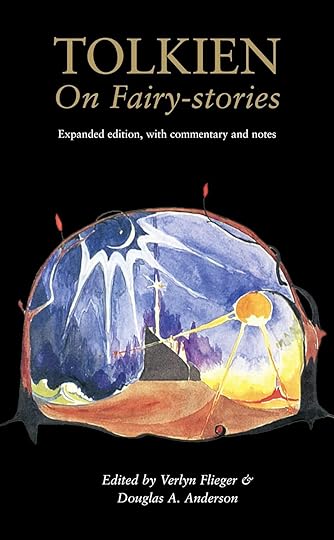

So I was utterly delighted when in 2008 Douglas Anderson and Verlyn Flieger edited and published all extant versions and MSS of “On Fairy-Stories”, together with a critical study of the history and reception of the essay. Their invaluable book is entitled Tolkien On Fairy-Stories and would have saved me hours of bewilderment and head-scratching over illegible MSS as a PhD student – but better late than never! The book has proved a revelation on all sorts of matters, and has reminded me of some really intriguing questions that had passed through my mind when studying the MSS in the Bodleian.

So what I would like to talk about today is probably the most heretical of Tolkien’s ideas evident in On Fairy-Stories (not that easily discernible in the essay as published but quite clearly articulated in the MSS and drafts now available from Doug and Verlyn’s wonderful new edition). I would like to talk about Tolkien’s belief in “real” elves and fairies. Not his Elves in the Secondary World of Middle-earth, but elves and fairies here, in the real, ‘Primary’ world.

In the essay as published Tolkien playfully hints to the possibility of such a belief on his part, but he leaves it vague enough to be taken as a creative way to discuss his topic.

For the trouble with the real folk of Faërie is that they do not always look like what they are… (Tolkien On Fairy-Stories: 31)

…if elves are true, and really exist independently of our tales about them… (Tolkien On Fairy-Stories: 32)

It is often reported of fairies (truly or lyingly, I do not know) that they are workers of illusion… (Tolkien On Fairy-Stories: 35)

God is the Lord, of angels, and of men – and of elves… (Tolkien On Fairy-Stories: 78)

However, specifically MS B of the essay makes things much clearer:

But wondering whether there are such things as fairies… I preserve to this day a fairly open mind on the existence of these things… (Tolkien On Fairy-Stories: 234)

And again:

I preserve to this day an open mind about the primary existence of these things… (Tolkien On Fairy-Stories: 286)

Again in MS B, in a longish and quite extraordinary passage (which is actually one I was able to decipher and have actually quoted and discussed in my book), Tolkien ponders on the “the Question of the Real (objective) existence of Fairies”:

They are not spirits of the dead, nor a branch of the human race, nor devils in fair shapes whose chief object is our deception and ruin. (Tolkien On Fairy-Stories: 254)

Now, this is an interesting point, and deserves a short pause. Tolkien is here talking about possible “theories” of what fairies and elves are. The last one (that fairies are devils in fair shape) is the oldest and least interesting, really: it’s the medieval Christian idea that elves and fairies are remnants of pagan religion, and really demons in disguise, making every effort to lead good men and women to sin and eventually to their damnation (though not all medieval Christianity perceived them in this way). A similar, but more forgiving, theory argued that the fairies were fallen angels, some of the host of angels that initially followed Lucifer when he fell from grace, and were then stuck in a kind of “limbo” between the spiritual and material worlds.

The first theory (that the fairies are spirits of the dead) links in nicely with folklore understandings of elves and fairies: as manifestations of the spirits of the dead in folklore communities, often babies that died before they were baptised.

The second theory (that fairies are a branch of the human race) was one also proposed by Victorian folklorists and it linked belief in fairies with the existence of a pygmy race in Europe before the coming of the Indo-European peoples. According to that theory, this small race initially hid away, lived in secret places in forests, but eventually faded away and disappeared entirely, and they remained in European memory as fairies. This idea was supported by such folklorists as Jacob Grimm, Benjamin Thorpe, George Webbe Dasent, and – perhaps more famously – David MacRitchie. Tolkien’s phrase in the published text of On Fairy-Stories that ‘Pygmies are no nearer to fairies than are Patagonians’ (Tolkien On Fairy-Stories: 34) points – I think – exactly to this interpretation and rejects it.[ii]

But then Tolkien goes on to tell us exactly what he thinks fairies are:

They are a quite separate creation living in another mode. They appear to us in human form… (Tolkien On Fairy-Stories: 254)

For lack of a better word they may be called spirits, daemons: inherent powers of the created world, deriving more directly and ‘earlier’ (in terrestrial history) from the creating will of God… (Tolkien On Fairy-Stories: 254)

They are in fact non-incarnate minds (or souls)… (Tolkien On Fairy-Stories: 255)

Thus a tree-fairy (or a dryad) is, or was, a minor spirit in the process of creation who aided as ‘agent’ in the making effective of the divine Tree-idea or some part of it, or of even of some one particular example: some tree. (Tolkien On Fairy-Stories: 255)

Tolkien’s idea of elves and fairies as spiritual beings associated with nature is not a new concept only found in the MSS of On Fairy-Stories. First of all, such beings exist in the first version of his mythology: in The Book of Lost Tales, there are elves and fairies, the size and general personality of whom is very different from the later exalted Elves of Middle-earth. These creatures are called interchangeably “elves” or “fairies”. They are cheerful and pretty and there is a light-heartedness in the way they narrate the great tales we know from the later Silmarillion, even when it comes to the most terrible deeds and incidents. The reader cannot help but visualize little fairy beings with silvery voices, partly due to their flowery narrative style.

But there is also another class of beings in The Book of Lost Tales, often called ‘spirits’, ‘sprites’ or ‘fays’, associated with particular landscapes: trees, woods, rivers, springs and mountains. They are often given names from Classical mythology or from British folklore. Have a look at this extract from ‘The Coming of the Valar and the Building of Valinor’ from The Book of Lost Tales:

With them [Manwë and Varda] came many of those lesser Vali who loved them and had played nigh them and attuned their music to theirs, and these are the Mánir and the Súruli, the sylphs of the airs and of the winds . . . About them [Aulë and Palúrien] fared a great host who are the sprites of trees and woods, of dale and forest and mountain-side, or those that sing amid the grass at morning and chant among the standing corn at eve. These are the Nermir and the Tavari, Nandini and Orossi, brownies, fays, pixies, leprawns, and what else are they not called, for their number is very great: yet must they not be confused with the Eldar, for they were born before the world and are older than its oldest, and are not of it, but laugh at it much, for had they not somewhat to do with its making, so that it is for the most part a play for them; but the Eldar are of the world and love it with a great and burning love, and are wistful in all their happiness for that reason. (Lost Tales I: 65-6)

Also, if we go back even further, to the first drafts of Qenya, Tolkien’s first invented language and the ancestor of Quenya, there are fairies that appear to live in flowers, and others associated with the landscape:

Ailinóne (_˘) a fairy who dwelt in a lily on a pool

Nardi a flower-fairy

Tetille a fairy who lived in a poppy

Nermi a field-spirit

tavar (tavarni) dale-sprites

oar (n-) child of the sea, mer-child

*oaris (-ts), oarwen, owen mermaid

*Ui Queen of Mermaids

nandin dryad

wingild- nymph

wingil(d) sea nymph

(see Qenya Lexicon, published in Parma Eldalamberon 12, pp. 29, 64, 66, 68, 70, 90, 90, 92, 97, 104)

So, from The Book of Lost Tales and Tolkien’s early linguistic documents it seems clear that there is a division between:

the elves and fairies, the later Elves of the mythologyand

the spirits associated with nature, who are given names from British folklore or Classical mythologyOne could argue (as I do in my book [iii]) that fairies, especially flower-fairies, were an integral part of the artistic inventory of poets and visual artists alike in the Victorian and Edwardian periods – and Tolkien started writing towards the end of the former and during the latter, so he was bound to be attracted by little winged fairies and relevant fairylore. Still, I think that Tolkien’s flower fairies and the nature spirits in The Book of Lost Tales are closer to what Victorian Spiritualists and Theosophists called the “elementals”, spirits of nature associated with earth, water, air or fire, first described in detail by the late medieval writer Paracelsus. In Middle-earth these spirits seem to be part of the creative energies that helped materialise the ‘Music of the Ainur’ and created the natural world.

These ‘elemental’ sprites remained in Tolkien’s mythology and later evolved into the Maiar, the ‘lesser spirits’ of the same order as the Valar, who aided the Valar in the shaping of the world. In one of his letters Tolkien explained that the Maiar were also involved in the creation of the world, but while the Valar were responsible for the whole creation, the Maiar were interested

‘only in some subsidiary matter (such as trees or birds)’ (Letters: 259).

But, aside from his invented mythology, MS B of OFS suggests that Tolkien believed in “elemental” fairies, spirits of nature, in the real, primary world. How can this belief be reconciled with his orthodox Catholic faith? Well, this might not be such a problem after all.

In John’s gospel, Christ’s words: “and other sheep have I that are not of this fold” (John 10:16) were often interpreted by the Victorians and Edwardians (especially followers of Theosophy and Spiritualism) as proof of the existence of fairies as a separate creation of God. Indeed, many religious men (both laymen and members of the clergy) had somehow incorporated the fairies into their system of belief. Paracelsus himself saw fairy beings as integral to his partially animist Christian belief system.

In MS B of OFS Tolkien seems to agree with the view that belief in fairies (or a parallel dimension of existence inhabited by such beings) is not contradictory to Christian Belief. He talks about

pure faierie… unclouded by doubt or theological suspicion. In fact owing to theological suspicion I am of course not discussing whether such faierie does exist or can exist philosophically or theologically. (Tolkien On Fairy-Stories: 256)

He even says that it is theological suspicion that has been responsible for popular belief often associating fairies with the devil or demonic powers (and promptly jots down the first few lines of te deum laudamus as if to exorcise such powers and declare his orthodox faith at the same time) (Tolkien On Fairy-Stories: 264). But he still seems to be defiant on the issue of real elves and fairies.

The elves and fairies he seems to believe in, and their “plane of existence” which is parallel but different to ours, are – for Tolkien – drawing ‘from the well of creative energy that a man feels to lie behind the visible world’ (Tolkien On Fairy-Stories: 260). He adds further on:

the normal world, tangible visible audible, is only an appearance. Behind it is a reservoir of power which is manifested in these forms. (Tolkien On Fairy-Stories: 270)

This view of a mystical vision of nature, a spiritual form of power and life that lies hidden beyond the visible world is very similar to ideas expressed by Francis Thompson, the Catholic poet whose work Tolkien admired greatly in his youth. In Thompson’s poem The Kingdom of God he writes:

O World invisible, we view thee,

O World intangible, we touch thee,

O World unknowable, we know thee,

Inapprehensible, we clutch thee!

And he adds:

The angels keep their ancient places; –

Turn but a stone, and start a wing!

’Tis ye, ’tis your estranged faces,

That miss the many-splendoured thing.

(Thompson 1913: 226)

This is the same poet who populated many of his poems with little elves and fairies, and talked about the presence of enchantment is our world, despite the fact that many of us have lost our ability to understand and appreciate it.

Now, these two short extracts from Thompson, point straight to another Catholic writer, one whose work Tolkien would have been undoubtedly familiar with: the recently beatified[iv] Cardinal Newman. Tolkien grew up at the Oratory in Birmingham, which was founded by Newman, and many of Tolkien’s early ideas seem to come straight out of Newman’s sermons. Newman talked a lot in his sermons about “the invisible world”, claiming that it is the proper place where God can be found. He also claimed that the other inhabitants of the “world invisible” are spirits of the dead, and angels.

Newman’s understanding of angels is very close indeed with Tolkien’s conception of fairies as “spirits of nature”. In his sermon on “The Powers of Nature” he writes:

But why do rivers flow? Why does rain fall? Why does the sun warm us? And the wind, why does it blow? Here our natural reason is at fault; we know, I say, that it is the spirit in man and in beast that makes man and beast move, but reason tells us of no spirit abiding in what is commonly called the natural world, to make it perform its ordinary duties. Of course, it is God’s will which sustains it all; so does God’s will enable us to move also, yet this does not hinder, but, in one sense we may be truly said to move ourselves: but how do the wind and water, earth and fire, move? Now here Scripture interposes, and seems to tell us, that all this wonderful harmony is the work of Angels… [The] course of Nature, which is so wonderful, so beautiful, and so fearful, is effected by the ministry of those unseen beings… I affirm, that as our souls move our bodies, be our bodies what they may, so there are Spiritual Intelligences which move those wonderful and vast portions of the natural world which seem to be inanimate… (Newman 1908: 359-61)

Bearing in mind the ideas expressed by Thompson and Newman, the flower-fairies and nature spirits in the Qenya Lexicon, and the elemental fays and sprites in The Book of Lost Tales, are not just an influence of Victorian whimsy, but also an effort to integrate spirits of nature in his early mythology. Newman calls them Angels, or “Spiritual Intelligences”, Thompson calls them angels or elves, Tolkien call them elves and fairies. And these spirits of nature, he believed to be real, true, semi-angelic powers that allowed the processes of nature to actually take place.

In the ever-surprising MS B of OFS, Tolkien refers to a memory from his youth:

I was walking in a garden with a small child. I was only nineteen or twenty myself. By some aberration of shyness, groping for a topic like a man in heavy boots in a strange drawing room, as we passed a tall poppy half-opened, I said like a fool: ‘Who lives in that flower?’ Sheer insincerity on my part. ‘No one,’ replied the child. ‘There are Stamens and a Pistil in there.’ He would have liked to tell me more about it, but my obvious and quite unnecessary surprise had shown too plainly that I was stupid so he did not bother and walked away. (Tolkien On Fairy-Stories: 248)

Due to a very recent article by John Garth in Tolkien Studies 7[v], we now know that this little anecdote is not an invention, but a real memory. The child Tolkien addressed was Hugh Cary Gilson, half-brother of Tolkien’s school friend Robert Quilter Gilson (Rob Gilson of the TCBS). Although Tolkien used this example to scorn flower-fairies in MS B of OFS, I think the memory is genuine of Tolkien’s different conception of flower-fairies at that time in his life.

Correspondence between Tolkien and another TCBS member, Christopher Wiseman, gives us further proof of this. When Tolkien presented the TCBS with some of his ‘fairy poems’ in 1916, planning to submit them for publication as a volume under the title The Trumpets of Faërie, Wiseman called some of them ‘freakish’ (Garth 2003: 119). He wrote to Tolkien:

You are fascinated by little, delicate, beautiful creatures . . . But I feel more thrilled by enormous, slow moving, omnipotent things . . . And having been led by the hand of God into the borderland of the fringe of science that man has conquered . . . I feel no need to search after things that man has used before. (quoted by Garth 2003: 121)

Wiseman’s argument was for the majesty of the solar system against the enchantment of fairies; he favoured science over folklore and belief in the supernatural. For Wiseman the fairies were only fit for Old Wives’ tales and belonged to a darker age of superstition. They were ‘the things that man has used before’, that is, before modern science. Wiseman saw Tolkien’s use of fairies and elves as anachronistic and unrealistic. Tolkien’s answer was that his own work ‘expressed his love of God’s creation: the winds, trees and flowers’. His elvish creatures ‘caught a mystical truth about the natural world that eluded science’ (Garth 2003: 121).

This is exactly Newman’s point in his sermon on “The Powers of Nature”:

Now all these theories of science, which I speak of, are useful, as classifying, and so assisting us to recollect the works and ways of God and of His ministering Angels… But if such a one proceeds to imagine that, because he knows something of this world’s wonderful order, he therefore knows how things really go on, if he treats the miracles of Nature (so to call them) as mere mechanical processes, continuing their course by themselves, – as works of man’s contriving (a clock, for instance) are set in motion, and go on, as it were, of themselves, – if in consequence he is, what may be called, irreverent in his conduct towards Nature… and if, moreover, he conceives that the Order of Nature, which he partially discerns, will stand in the place of the God who made it, and that all things continue and move on, not by His will and power, and the agency of the thousands and ten thousands of His unseen Servants, but by fixed laws, self-caused and self-sustained, what a poor weak worm and miserable sinner he becomes! Yet such, I fear, is the condition of many men nowadays, who talk loudly, and appear to themselves and others to be oracles of science, and, as far as the detail of facts goes, do know much more about the operations of Nature than any of us. (Newman 1908: 363-4)

Elves, fairies, angels, elemental spirits, spirits of nature: Tolkien’s early beliefs tap into anxieties and interests of his time, with Spiritualism and Theosophy very much in vogue, but also remain strangely compatible with his Catholicism. Could we consider Catholicism as a more mystical brand of Christianity that allows for such beliefs? Rudyard Kipling certainly thought so!

In Kipling’s 1906 story story “Dymchurch Flit”, later published as part of Puck of Pook’s Hill of the same year, there are fairies who live happily in Romney Marsh in East Sussex, until ‘Queen Bess’s father’ came ‘with his Reformatories’:

A won’erful choice place for Pharisees, the Marsh, by all accounts, till Queen Bess’s father he come in with his Reformatories… This Reformatories tarrified the Pharisees same as the reaper goin’ round a last stand o’ wheat tarrifies rabbits. They packed into the Marsh from all parts, and they says, “Fair or foul, we must flit out o’ this, for Merry England’s done with, an’ we’re reckoned among the Images.”‘ (Kipling 1994: 189)

The implication is that the fairies were driven out of England because of Henry VIII’s (Queen Elizabeth I’s father) break with the Catholic faith and the formation of the Church of England. Kipling’s fairies are afraid that this will lead to their persecution as they exclaim: ‘Fair or foul, we must flit out o’ this, for Merry England’s done with, an’ we’re reckoned among the Images’. Indeed, in the sixteenth century the reformation of the church in England was followed by the desecration of monasteries and destruction of ‘idolatrous’ religious images. Iconoclasm at its extreme considered religious images to represent a sinful adoration of objects, rather than the scene or figure they represented. Kipling’s fairies, therefore, see Catholicism as a ‘friendlier’ Christian denomination that retains mysticism and could accept them as part of God’s creation. When they see the ‘images’ torn down, they embark on a boat and sail to France.

Tolkien’s belief in elves and fairies in the real, primary, world, therefore, is not as “heretical” as I promptly labelled it in the beginning of my talk – but, then, I was trying to get your attention and intrigue you! Newman’s angels, Thomson’s elves and Tolkien’s elves and fairies are the same spiritual beings that can live happily within a Christian understanding of the world, and create the necessary “supernatural” enchantment, making the way we look at the world new, exciting and mystical again: after all, isn’t that what fantasy literature does anyway?

NOTES

[i] Oxonmoot 2010 was held at Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford.

[ii] For these Victorian theories of the nature and function of fairies see Silver 1999, Bown 2001, and Purkiss 2000.

[iii] See especially Chapter 3: “’Fluttering Sprites with Antennae’: Victorian and Edwardian Fancies”

[iv] Newman was beatified on 19 September 2010 (literally days before Oxonmoot 2010) and was later canonised in 2019.

[v] See Garth 2010.

REFERENCES

Bown, Nicola, Fairies in Nineteenth-century Art and Literature (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001).

Fimi, Dimitra, Tolkien, Race and Cultural History: From Fairies to Hobbits (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008)

Garth, John, Tolkien and the Great War: The Threshold of Middle-earth (London: HarperCollins, 2003).

Garth, John, “J.R.R. Tolkien and the Boy Who Didn’t Believe in Fairies”, Tolkien Studies, 7 (2010), 279-90.

Kipling, Rudyard, Puck of Pook’s Hill (London: Penguin, 1994 (first published in 1906)).

Newman, John Henry (1908), Parochial and Plain Sermons, Volume 2, Sermon 29: “The Powers of Nature”, pp. 359-61. Available at: https://www.newmanreader.org/works/parochial/volume2/sermon29.html

Purkiss, Diane, Troublesome Things: A History of Fairies and Fairy Stories (London: The Penguin Press, 2000).

Silver, Carole., Strange and Secret Peoples: Fairies and Victorian Consciousness (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999).

Thompson, Francis, The Works of Francis Thompson. Vols 1 and 2 (London: Burns & Oates, 1913).

Tolkien, J.R.R., Tolkien on Fairy-Stories, ed. by Verlyn Flieger and Douglas A. Anderson (London: HarperCollins, 2008).

Tolkien, J.R.R., The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, edited by Humphrey Carpenter with the assistance of Christopher Tolkien (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1981).

Tolkien, J.R.R., The Book of Lost Tales, Part One, edited by Christopher Tolkien (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1983).

December 12, 2022

Goblins in Dickens’s Pickwick Papers and Tolkien’s The Hobbit

*This blog post is a short extract from a paper I gave at Tolkien Society’s 2012 conference (Return of the Ring, Loughborough University, 16-20 August 2012), titled: “Elves, Goblins and Other ‘Fairy’ Things in The Hobbit: Tolkien’s Victorian and Edwardian Inspirations”.

I’ve written and spoken many times in the past on Tolkien’s creative engagement with the imagery of Victorian fairies, both in his early poems, and in the first version of his mythology, as recorded in The Book of Lost Tales[i]. But I want to focus a bit more on goblins this time round, especially in The Hobbit, and to explore how Tolkien’s fascination with “fairy things” continued well after he abandoned the Lost Tales.

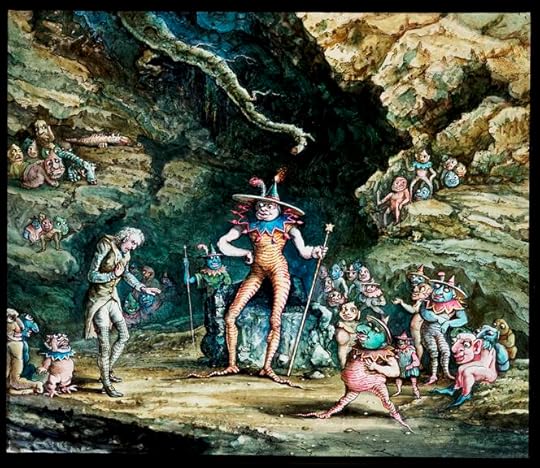

Goblins were part of the inventory of “fairy creatures” amply used in Victorian paintings, illustrations and literature – and this was, of course, the time J.R.R. Tolkien was born and grew up. Victorian fairy painting often combined beautiful fairies with grotesque goblin- or dwarf-like creatures that seem mischievous at best, and evil at worst. See, for example, Richard Dadd’s celebrated painting The Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke (below), a masterpiece of its kind, which really repays close observation. Some of the creatures here are beautiful and majestic, others are misshapen, grotesque and somewhat uncomfortable to look at. Clearly, Victorian fairies were not only conceived as the stuff that dreams are made of, but also nightmares!

Richard Dadd. Fairy Fellers’ Master-Stroke. 1855–1864. Oil on canvas. 54 × 39.5 cm. Tate Gallery, London.

Richard Dadd. Fairy Fellers’ Master-Stroke. 1855–1864. Oil on canvas. 54 × 39.5 cm. Tate Gallery, London. Detail from Richard Dadd’s Fairy Fellers’ Master-Stroke.

Detail from Richard Dadd’s Fairy Fellers’ Master-Stroke.

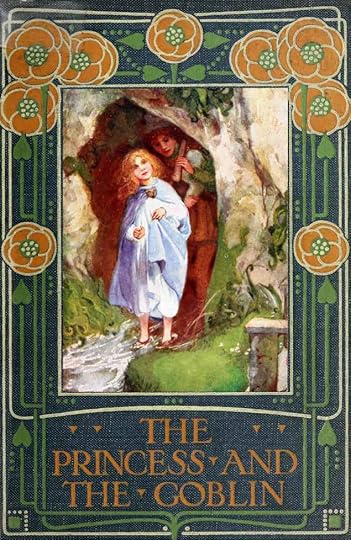

In The Hobbit, Tolkien’s goblins are not described in detail, but we first encounter them coming out of the earth, literally springing out of a crack in the cave where the Dwarves and company have found temporary shelter. The idea of goblins living underground is very much at the centre of George MacDonald’s children’s fantasy books The Princess and the Goblin and The Princess and Curdie. A number of Tolkien scholars, including Douglas Anderson, John Rateliff, have commented on MacDonald’s influence on Tolkien[ii], but I would like to draw your attention to another Victorian text (and its illustrations) that portrays goblins living underground and shows similarities with the behavior of the Hobbit goblins.

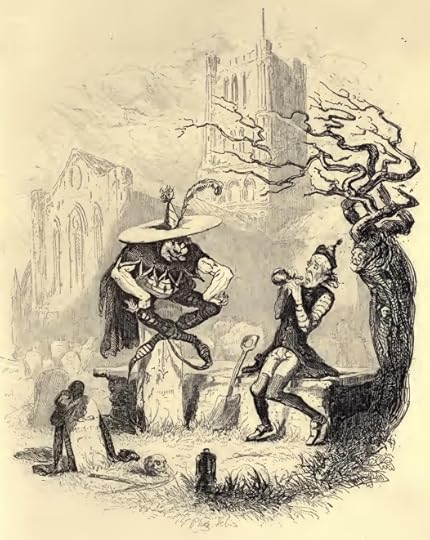

This is chapter 29 of The Pickwick Papers, by Charles Dickens: “The Story of the Goblins who stole a Sexton”. Most people know this little story as the “prototype” of A Christmas Carol. The sexton in question is Gabriel Grub, “an ill-conditioned, cross-grained, surly fellow – a morose and lonely man, who consorted with nobody but himself”, a man who hates Christmas and children. On Christmas Eve, he decides to spend the night by digging a new grave for the next funeral at the church, but he meets there the goblin king and he is spirited away by the goblins. He is taken to a cave, where he is shown visions of family love, goodwill and charity, while in-between these scenes he also receives some abuse from the goblins in the form of kicks and beatings! By Christmas morning he is a different man! Gabriel Grub is, therefore, the prototype of Ebenezer Scrooge, whose supernatural experience on Christmas Eve transforms him and changes his heart.

Illustration from This is chapter 29 of

The Pickwick Papers

, by Charles Dickens: “The Story of the Goblins who stole a Sexton”.

Illustration from This is chapter 29 of

The Pickwick Papers

, by Charles Dickens: “The Story of the Goblins who stole a Sexton”. Dickens’s goblins have “long, fantastic legs” and “sinewy arms”, they “leer maliciously” and they “laugh shrilly”. When they first reveal themselves to Gabriel, they all appear en masse, “whole troops of goblins”, just like in The Hobbit the goblins jump out all at once, “big goblins, great ugly-looking goblins, lots of goblins, before you could say rocks and blocks”.

Eventually, the goblin king grubs Gabriel and together they sink “through the earth” underground. In The Hobbit, Bilbo dreams that the floor of the cave in which he’s found himself, together with Gandalf and the dwarves, is “giving way”, and that he begins to “fall down, down, goodness knows where to”, until he wakes up and realizes this is no dream at all, and that the goblins lead him and the dwarves “down down to Goblin-town… far underground”.

Gabriel finds himself in a cave:

Gabriel Grub…found himself in what appeared to be a large cavern, surrounded on all sides by crowds of goblins, ugly and grim; in the centre of the room, on an elevated seat, was stationed his friend of the churchyard [the goblin king]…

(Charles Dickens, The Pickwick Papers, chapter 29)

Compare this with The Hobbit (I’ve highlighted similar diction):