Akiva Hersh's Blog

March 11, 2022

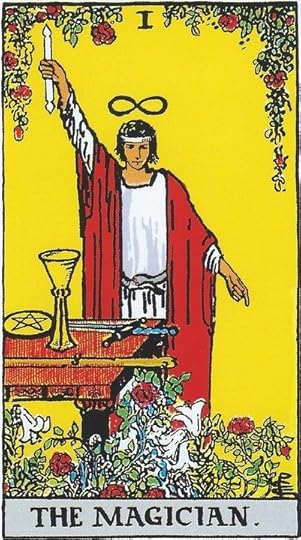

The Magus and The Fool Magic Tricks

March 5, 2022

Book Review of Stolen Moments of Joy by Hamour Baika

Stolen Moments of Joy by Hamour Baika is an LGBT contemporary fiction novel that unfolds against the backdrop of police brutality in Baltimore and weaves themes of racism, physical and sexual abuse, and survival with a triumphant delicateness.

Abdul moved to the US from Afghanistan when he was a teenager. Now twenty-four, he lives in Baltimore and is in a relationship with Cliff, who degrades him verbally and physically abuses him. Abdul carries wounds from his past and puts up with Cliff because he feels he doesn’t deserve anyone better (or he can sometimes convince himself that Cliff is the perfect boyfriend). But then, one day, while working at his job in a hotel, Abdul meets Tyrique, a handsome journalist from out of town. Abul’s affair with Tyrique is gentle and loving, contrasting Cliff’s bad behavior. But what might have been a positive jumping-off point into safety for Abdul turns into another loss when Tyrique leaves Baltimore.

Deepening dissatisfaction with Cliff pushes Abdul from one tryst to another, inducing guilt and shame. Cliff regularly calls Abul “stupid” and orders him around like a slave in front of his friends. Abdul hates this but carries on. One wonders how a handsome young man can stay in such a terrible relationship where he has to placate his lover and meet the demands of his overgrown ego constantly. But then the reader gets a clearer picture, chapter by chapter, of the world in which Abdul grew up. Baika introduces us to bacha bazi, an illegal practice where boys are made to dress as women, dance for men, and then are sexually abused by the highest bidder. Witnessing this atrocity is one of the many trauma-inflicting experiences young Abdul had to endure. And while he is no longer in danger in Afghanistan, he must come to terms with the ongoing abuse he has allowed himself to take from Cliff.

Stolen Moments of Joy is a story of loss and redemption. Baika’s strength is creating a character like Abdul, who makes us long for his well-being, cringe at his choices, all the while rooting for him to make his life better. However, there were times when Baika pulled the reader from the story into granular detail about physical movements, setting, and exposition. Baika’s stylish prose is enough when painted lightly. Yet there were passages where it felt he dragged the brush too thickly over the canvas. The dialogue structure was evident and advanced the plot, but it felt forced and artificial in places. Many of the characters seemed to speak with the same “voice.”

Overall, Baika’s story moves and brings essential issues like abuse in LGBTQ+ relationships and sexual abuse to the foreground. For those reasons alone, I would recommend Stolen Moments of Joy, for, in every art form, there is the power to produce change.

Akiva Hersh is a Reedsy Reviewer. This review can also be found on their site.

February 23, 2022

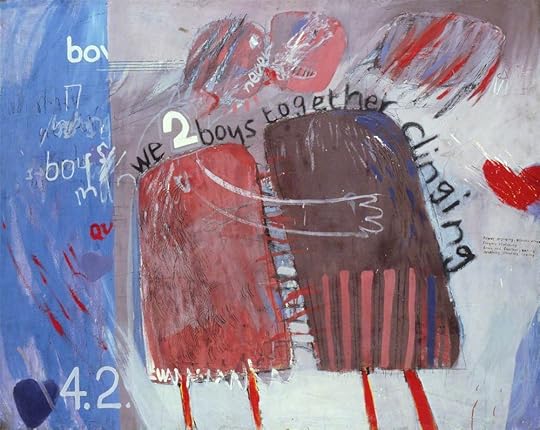

Book Review of Two Boys Kissing by David Levithan

We Two Boys Together Clinging by David Hockney

Two boys Kissing by David Levithan is not a book about boys kissing. Well, it is, but it’s about so much more like the lost wisdom of the generation before us who lived (and died) through the AIDS crisis. And the pain and self-hatred young LGBTQ+ people cope with every day, sometimes by themselves. And about the uncertainty of love whose tireless seas demand everything and sometimes give nothing back. And it’s about standing firm in who we are.Two Boys Kissing has been a novel of contention in the public eye. Libraries want it banned. Conservatives claim it is pornographic. When I heard these things, I immediately decided this was a book I needed to read now. And I’m glad I did. Not because I could relate to the pain and the suffering the gay characters experienced (which I did). And not because it gave me a good, ugly cry at the end (it did that too). But because this novel is a crucial contribution for it connects the current generations to the wisdom of LGBTQ+ history, and this is a vital thing. When we forget our history, we become unmoored and drift dangerously on the uncertain tides of social narratives and political agendas.

Two boys Kissing features Harry and Craig, two boys no longer dating but committed to breaking the most extended kiss registered in the Guinness World Records. The rules? Kiss for at least thirty-two hours, twelve minutes, and ten seconds. Their lips must touch the entire time—no bathroom breaks. Food and water have to be consumed while kissing. And it must be recorded for proof.

While that marathon is taking place, we meet other characters like Avery, a trans boy, on a date with Ryan for the first time. He has to push past his fear and rejection to get that far. Neil and Peter are two boys dating but struggling because Neil’s parents won’t acknowledge that he is gay. Cooper is a gay teenager who has fled from his home and family because he’s dying from loneliness and rejection. He engages in risky sexual behavior, leaving him feeling more empty. And then there are the dead, the victims of the AIDS crisis, who narrate the story as a collective “we.” Their voices made me weep. They see what is happening to the characters and desperately wish to intervene but cannot. They want to offer wisdom, but they can no longer be heard. “He is on the verge of finding that very hard truth—that it [life] will never be complete, or feel complete. This is something you only have to learn once—that just like there is no such thing as forever, there is no such thing as total.”

At one crises point in Cooper’s life, the dead say:

Listen to us. We fruitlessly demand that you listen to us. We shit blood and had our skin lacerated and broken by lesions. We had fungus grow in our throats, under our fingernails. We lost the ability to see, to speak, to feed ourselves. We coughed up pieces of ourselves and felt our blood turn to magma. We lost the use of our muscles and our bodies were reduced to collections of skin-encased bones. We were rendered unrecognizable, diminished and demolished. Our lovers had to watch us die. Our friends had to watch as the nurse changed our catheters, had to try to put aside that image as they laid us in caskets, into the ground. We will never kiss our mothers again. We will never see our fathers. We will never feel air in our lungs. We will never hear the sound of our voices. We will never feel snow or sand or take part in another conversation. Everything was taken away from us, and we miss it. We miss all of it. Even if you cannot feel it now, it is all there for you.

Can you hear them speaking to us? I can. Are you listening? I hope I do.

Two Boys Kissing affirmed my identity, named my pain and enfolded it within the collective history of those who have carried the same burdens of shame, fear, and self-loathing long before me. Read this book. Tell everyone to read this book. And let the book banners go to hell.

February 14, 2022

Q & A with Clarissa Pattern and Akiva Hersh about The Magus and The Fool

CP: I'd love to know at what point in your creative process you came upon your title?

AH: The title was immediate for me. I knew Jacobi was going to be far more an illusionist than Gatsby and Carry would follow him off the cliff if it meant getting close to him. I have a little background in tarot so the Magus (magician) and Fool archetypes begged for a title right on the nose.

CP: You mention in your blog about The Great Gatsby coming into the public domain, was it a novel you were drawn to retelling before then, or were you considering several options? Also what were your thoughts on approaching the anti-Semitism some people see in The Great Gatsby?

AH: I was not initially drawn to Gatsby as a retelling. I liked the novel, the movie was just fine but I was considering other works. As I wrote out a few sample chapters for several books in the public domain, I fell in love with the characters I had conceived of for a Gatsby retelling and they just inhabited my mind like a hermit crab in a shell.

Regarding antisemitism, I am a Jew and I wanted to portray flawed characters of all types and narrow down the racism to Fallon, leaving the other characters presenting as “woke.” I felt that Fallon had the internal capacity to carry this burden more than the other characters. She is not brittle. She is not ashamed of her opinions and while they may not be in vogue, she is true to herself up to a point.

CP: I was very interested in the character of Fallon, her racism automatically aligns her with far-right beliefs, but she surprised me at one point by making a comment that sounded like she was against the conservatives’ anti-Global Warming stance? And also I was interested whether she is not interested in Donovan's bisexuality and Levi's transness or if it is something she reluctantly tolerates but she does have homophobic feelings underneath?

AH: On the surface, her racism and rants against conservatives seem to conflict. However, I wanted to show that people are complex and that human beings are reliably inconsistent.

Donovan’s bisexuality and Levi being trans is something Fallon chooses to overlook—especially in Donovan’s case. Why? Because Fallon struggles with gray areas. She prefers the stark black and white sorting when it comes to morals, business, and relationships.

CP: When you were writing how consciously close did you aim to stay to the originals?

AH: I was not interested in carbon copying them and merely swapping gender or sexuality. Each one has a different personality and different motivations from Fitzgerald’s characters. While there are similarities to their character arcs, I think that is where the resemblance ends.

CP: Another question I wanted to ask is actually about the significance of changing location? Did you move it to a place you knew better or is it a comment on how the USA social scene of the rich and famous is different now?

AH: I felt Long Island has changed so much since the 1920s but was no longer “fresh.” I lived in Austin for over half of my life. It’s a liberal, “blue” oasis amidst the “red” state of Texas, and yet the issues of social class, race, inequality are played out there in so many interesting ways.

February 13, 2022

Review of Airy Nothing by Clarissa Pattern

Clarissa Pattern’s Airy Nothing is a tale of love, hope, and longing and one chock full of faeries, hobgoblins, and very relatable characters. The story centers around John, a “badly made boy,” who goes on a quest for the Faerie Queene in seventeenth-century London in hopes she will help him become a man and make him “new and clean.” His yearning for this comes from past abuse, loss, and rejection.

Not long into his journey, John meets a thief, Jack, who thinks John is a girl and kisses him in a public alley. John swoons but worries about what Jack will think when he discovers the truth about him.

The two make fast friends as Jack introduces John to a world of new people and experiences, but as the story progresses, one worries that Jack only intends to use John. Whatever his aims, Jack and John help the other in ways they have never encountered before. And when they face a common enemy, their relationship takes a swift turn.

This fantasy/coming of age story rings genuine notes about identity, acceptance, and learning to face reality with support from others. At one point, Jack tells John, “If you want to be something, be it, do not fret over what others are thinking,” and this is undoubtedly a central theme in the novel.

Pattern’s research shines as she brings a fantastical London to life with some characters who get close to one’s heart and others who intimidate and repulse. Her use of language keeps the reader engaged and entertained. Some scenes gave me chills, and some brought tears to my eyes.

Airy Nothing is a significant contribution to LGBTQ+ literature. I recommend reading it and do hope to see it in school libraries as well; words open worlds, and Pattern has created a universe where finding acceptance of oneself can begin with the turn of a page.

February 1, 2022

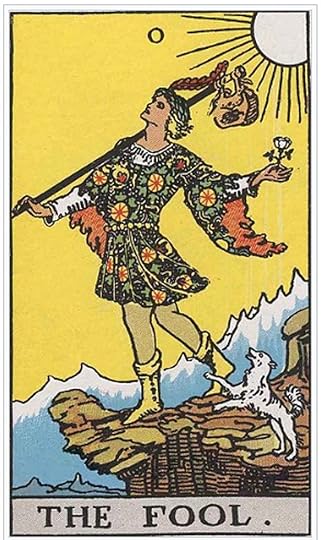

What Do the Magus and the Fool Represent?

The Magus

A Magus (magician, pronounced: ˈmāɡəs) is the first tarot card after The Fool in the Major Arcana. Some of its meanings are new beginnings, insight, willpower (or even a weakness of the will), cunning, and diplomacy.

If it is reversed (turned upside down), it can indicate misuse of power and disgrace.

The Fool

The Fool is usually placed before the Magus. This card can mean folly, extravagance, intoxication, punishment for mistakes, and even spirituality.

Reversed, it can indicate negligence, apathy, and absence.

In the novel, all of the characters deal with misfortune, loss, frustration, and a frail hope for what they dream of coming true. However, one character represents The Magus and another, The Fool. After you read the book, leave a comment to tell me who is who.If you are interested in learning more about tarot archetypes, I highly recommend the world’s foremost authority on tarot, Rachel Pollack.January 7, 2022

Some Things I've Learned From 1972-2022

The year is now 2022. To mark the occasion here are some things I’ve learned over the last fifty years. On Self-Care:

The year is now 2022. To mark the occasion here are some things I’ve learned over the last fifty years. On Self-Care:

Love is never enough to maintain a relationship. Love also requires you to be fierce. If you’re not fierce, you’re not in love.When your marriage is no longer working, get a divorce. If you have kids, don’t hang that albatross of a relationship on them. They will learn more about life by seeing you live your authentic self than watching you live the hologram your partner expects you to be.Demand blind loyalty from your family and closest friends. If they can’t give you that steer clear. On Being A Person:

Love is never enough to maintain a relationship. Love also requires you to be fierce. If you’re not fierce, you’re not in love.When your marriage is no longer working, get a divorce. If you have kids, don’t hang that albatross of a relationship on them. They will learn more about life by seeing you live your authentic self than watching you live the hologram your partner expects you to be.Demand blind loyalty from your family and closest friends. If they can’t give you that steer clear. On Being A Person:  Pay attention to how you feel when you’re alone with yourself. If you’re uncomfortable with you chances are people pick up on that. Do everyone a favor and get professional help.Recognize when you’ve run out of fucks to give. Then cut loose whatever is demanding those fucks. For fuck’s sake smile at everyone you see. They need it as much as you do.On Creativity:

Pay attention to how you feel when you’re alone with yourself. If you’re uncomfortable with you chances are people pick up on that. Do everyone a favor and get professional help.Recognize when you’ve run out of fucks to give. Then cut loose whatever is demanding those fucks. For fuck’s sake smile at everyone you see. They need it as much as you do.On Creativity:  Most people are creative. So tap into that. If you lack that drive, surround yourself with creative people who are smarter than you.If you aren’t creative and really suck at trying to be, own that. Then learn to appreciate art, literature, Music, and film. Spare the rest of us from your over-inflated ego.

Most people are creative. So tap into that. If you lack that drive, surround yourself with creative people who are smarter than you.If you aren’t creative and really suck at trying to be, own that. Then learn to appreciate art, literature, Music, and film. Spare the rest of us from your over-inflated ego.

December 23, 2021

Why The Great Gatsby Needs a Queer “New Telling”

Speculations around the narrator in The Great Gatsby, Nick Carroway, center around his sexuality. Literature professors point to the interactions between Nick and Mr. McKee in Chapter Two as evidence of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s veiled references to Nick’s homosexuality—veiled on account of the homophobia of the time. David Giunta provides an excellent treatment here. Queer theory points to Fitzgerald’s penultimate magician’s trick of distraction. While the reader is misdirected by Gatsby’s futile dream of winning over Daisy, Nick is pining away for Gatsby himself behind the curtain.

But was there something more profound than homophobia at work when Fitzgerald wrote The Great Gatsby? The culture editor at The Wall Street Journal, Cody Delistraty, thinks so. In his article in The Paris Review, Distncly Emasculated, he writes, “Fitzgerald didn’t use his writing to mask his sexual insecurities to the extent that Hemingway did, but he perceived his lack of control—in his marriage with Zelda, his writing, and his “emotional bankruptcy,” which he wrote about extensively in The Crack-Up—as not just feminine but homosexual. It was an identity in which he saw emotional chaos.” The article goes on to suggest that it was Fitzgerald’s fluid sexual identity that drove him to relocate to Europe seeking “the freedom from moral scrutiny.”

But is the Hemingway/Fitzgerald connection strong enough to suggest that Fitzgerald was trying to work out his inner demons in Gatsby? Maggie Gordon Froehlich makes a startling observation in her essay Jordan Baker, Gender Dissent and Homosexual Passing in The Great Gatsby:

…throughout his life, Fitzgerald was terrified of being identified as homosexual and uneasy about his sexuality and sexual performance, and he expressed a vehement hatred of, in his word, “fairies.” Homosexuality is treated explicitly in Fitzgerald’s next novel, Tender is the Night (1934), and the author’s notes for the novel show that he was, at least by that time, familiar with works on sexology: “Must avoid Faulkner attitude and not end with a novelized Kraft-Ebing [sic]—better Ophelia and her flowers” (qtd in Bruccoli 334). So in some ways, it seems strange that homosexuality is not addressed in The Great Gatsby. Strange, that is, unless we recognize sexual transgression as the open secret of the novel.

When I began researching Gatsby after it entered into the Public Domain, I wondered how an alternate version—a new telling, not a retelling—might go. If Fitzgerald was alive today and could have evolved beyond his own bias of sexuality and gender, could his “great American novel” include diverse characters, specifically from the LGBTQ+ community? The answer to this question became The Magus and The Fool, a modern new telling of The Great Gatsby where my narrator, Carry Iverson, is openly gay and quite attracted to Oskar Jacobi—the rich, mysterious neighbor who is in love with Carry’s cousin Donovan, a bisexual man married to a powerful and cunning woman who is out to destroy Jacobi to keep her husband from straying. I also transformed Jordan Baker into a trans man, Levi Safran, who has a romance with Carry; their relationship explores the passions and the challenges between a gay CIS gender male and a trans person.

I chose to follow the form of the original loosely. My goal was to update the setting and language, some of the themes, and the plot. However, I resequenced a few key scenes and, of course, added new scenes and dialogue in service of queering the text and making it more diverse.

Finally, there is a twist ending. In my view, the way I ended The Magus and The Fool is consistent with the spirit of Fitzgerald’s novel. Still, it offers a resolution to the major crisis and character arcs that Fitzgerald may not have been able or willing to reach for.

October 1, 2020

Gods With Anuses

Viewers of the first presidential debate between President* Trump and Joe Biden were given a gift, the rare glimpse of a human being lost in his own theater of narcissism, what Freud called our desperate absorption with ourselves. With his bullying, his ad hominem attacks, and his uncontrollable interruptions, Trump exposed his lesser angels and our own.

Trump’s core value jumped through the camera and grabbed us by the throats—everything outside of himself doesn’t matter. His self-proclaimed “good genes,” superior bloodline, and “high IQ” were death-defying symbols displayed around him like flowers surrounding a casket at a wake; desperation and loss masked by fragrance and appearance. But the gift nestled inside the gore is the opportunity to see humankind’s inability to reconcile our heroic illusions with our frailty and neediness. Trump’s shit-show is an invitation to face our human dilemma.

We need to feel self-worth. This need drives our narcissism. And like Trump, we all have our own symbols of cosmic significance that we employ to constantly compare ourselves to others in order to ensure we aren’t in second place. And if we come up lacking, we are overtaken by a gripping sensation of tragedy—we have failed to be unique, to rise above everyone and everything to prove that we count. The greatest gift of that “debate” was to witness another human gripped by the fear of death.

Most of us might not be as crass as Donald Trump to fully own our illusion that we are superior and deserving of the title “hero.” We might shy away from such a moniker. But deep down we crave the affirmation and mask our need for it by following our culture’s norms: a huge bank account, an expensive car, the best lawn on the cul-de-sac, children that we mold in our image to carry ourselves into the future, or no children to tether us so that we can travel the world just to post selfies on social media as if to say, “I was here.” But we cannot blame Trump for behaving badly. Our society has erected a scaffolding by which we build this hero image and we either worship or revile those who publicly embrace it.

This cultural edifice can be structured around religion, science, fanaticism, magic; it can be civil or debased, it doesn’t matter, any form is a vehicle that transports us to destination Meaningfulness. But what would happen if we were honest about all of this? What would it be like if everyone was forthright in their desire to be primary in the universe? How would society and culture accommodate everyone’s need to be valuable? We see a hint of an answer in the struggle of social movements of the day where oppressed people groups are clambering for their rights and demanding equality. Minorities, LGBTQ+ communities, immigrants, women, are all really crying out for the return of what has been stolen from them—their primary place in society, the world, and on an individual level, the universe. And how do the other groups in the culture respond? They get really pissed off. They reassert their primary place through violence, rule of law, religious decrees, and by restricting access to power and agency. What are people so frightened of? How have we arrived at a place where a man-child—the penultimate symbol of this human condition—has been put into power and reigns largely unchecked, who is both adored and hated the world over? The answer is ugly.

It is painful to become aware of the games we play to win the feeling that we are important. It is terrifying to admit the lengths we go through to acquire self-esteem. But what we scratch and kick against the most is to question whether this cosmic value system that affords us meaning and validation is true and real. Without the symbols of our heroism who are we? Perhaps this is why we hate what we witnessed in Trump’s behavior during the debate (and saw over and over throughout his last four years in office). Our myths of significance are falling apart. Religion isn’t saving us, politics bring no relief, the pandemic has left us socially empty and we stand in our nakedness now more than ever. We are depressed and anxious about it.

So we carry on despite the glimpses of our dilemma and pretend we are robed in glory. We are gods with anuses, as Ernest Becker characterized us. Perhaps if we realize we can’t elect real heroes, we are unable to purchase enough things to feel worthy, that the right relationships or jobs won’t cause other people to favor us more than they wish to be favored, and that we will all feed the worms in the end as have our ancestors and so will our progeny, maybe then we could tip the scales of our condition and choose to reject the anxiety of death (which will never leave us alone) and decide to be brave in the face of it all. Maybe this kind of honesty would make us tolerant, inclusive, equitable, and authentically human.

January 22, 2020

Boy in the Hole is now available on all digital platforms!

bit.ly/BITHGooglePlay

bit.ly/AppleBooksBoyintheHole

bit.ly/BOYINTHEHOLE (Amazon)

bit.ly/KoboBITH

bit.ly/NookBITH