Damon Wells's Blog

November 27, 2025

How to Align Your Leadership

You know your track record. You know which roles felt natural and which required constant effort. You know where you’ve succeeded and where you’ve struggled.

What you likely lack is awareness of the complex psychological machinery underneath those patterns and exactly how that combined with your environment, makes you the leader you are.

I’m talking about the internal systems that process information, regulate emotions, generate decisions, and produce behavior under pressure. These systems vary systematically across individuals. They create fairly predictable response patterns. And those patterns determine leadership behaviors and outcomes most of us never examine.

The Manufacturing LeaderConsider a manufacturing operations leader who built her entire reputation over fifteen years. She prevented problems before they emerged. She created systems that ran smoothly. She optimized every process. Her internal wiring included high conscientiousness, systematic thinking, process orientation, detail focus, low tolerance for ambiguity.

In manufacturing operations, this machinery produced excellence. Clear metrics. Stable processes. Predictable outcomes. Every success reinforced her belief that good leadership meant being organized, methodical, and thorough.

Then leadership promoted her to run innovation initiatives.

Within six months, she was drowning. Her systematic nature kept trying to impose process where the work demanded experimentation. Her detail focus kept catching problems that needed to be left alone until concepts proved viable. Her low tolerance for ambiguity kept seeking certainty where the work required comfort with unknowns.

What happened? It was the same person with the same internal wiring. Opposite results.

The machinery remained constant but the environmental forces it collided with changed. That collision is the thing few of us think about. We typically work on building “leadership skills,” with little regard to the context.

Think of yourself like an athlete. An athlete must possess general traits, like stamina and strength, but to excel, the athlete must practice. The closer the practice is to the competition, the higher the skills developed. The Athlete must match the Arena.

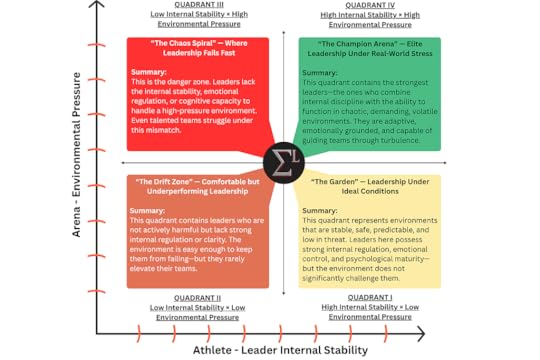

[image error]These are the metaphors:

The Athlete represents your psychological machinery. Your personality architecture, neural circuits, cognitive patterns, communication defaults, stress responses. The internal systems that determine how you process pressure, make decisions, and produce behavior. Every leader brings different machinery to the work.

The Arena represents the environmental forces surrounding you. Threat level, resource availability, volatility, tempo, incentive structures, network scale. These forces vary dramatically across contexts. Manufacturing operations present different forces than innovation work. Routine hospital administration presents different forces than emergency services.

The Alignment represents the multiplicative collision between Athlete and Arena. When your machinery matches the environmental forces, you thrive. When it misaligns, you struggle. The same capabilities produce excellence in one Arena and frustration in another.

Five Athlete SystemsYour leadership effectiveness emerges from five major systems operating beneath conscious awareness.

Personality architecture (Five Factor Model) forms the foundational structure. How much you seek novelty versus prefer familiar approaches. How organized and disciplined you naturally operate. Whether you get energy from people or need solitude to recharge. How much you prioritize harmony versus competition. How sensitive you are to stress and setbacks.

Neural circuits determine your baseline responses. Your threat-detection system runs faster or slower than others. Your reward sensitivity makes certain incentives motivating and others irrelevant. Your cognitive processing determines whether you think fast and shallow or slow and deep.

Cognitive patterns shape how you analyze information and make decisions. Some people naturally break problems into first principles. Others match patterns to previous experiences. Some gather extensive data before deciding. Others make rapid choices with incomplete information.

Communication defaults govern how you exchange information with others. How directly you state things. How much you invest in relationship depth versus breadth. Whether you communicate through explicit detail or implicit shared understanding.

Stress responses determine how you function under pressure. How quickly pressure activates your stress system. How long it takes you to recover after pressure spikes. Whether you stay calm until extreme pressure or feel activation early.

These systems interact to create your overall profile. They activate differently under different environmental conditions. When conditions and machinery align, you feel flow. When they misalign, you feel friction.

The Multiplication That MattersThis is where leadership development gets it wrong. Traditional approaches treat your capabilities as fixed assets that produce consistent returns across contexts. They assume building more skills always improves outcomes. (See Most Leadership Models are Garden Tools)

The math works differently. Your effectiveness equals your capabilities multiplied by environmental alignment. Strong capabilities times strong alignment equals excellence. Strong capabilities times weak alignment equals struggle.

[image error]The manufacturing leader had strong capabilities. Her conscientiousness, her systematic thinking, her attention to detail. These multiplied beautifully with operations forces. Operations rewarded thoroughness, planning, risk reduction. Her Athlete times that Arena equaled excellence.

Innovation presented different forces. It rewarded experimentation over systematization, speed over thoroughness, comfort with failure over risk reduction. Her identical capabilities multiplied against those forces produced struggle. The Athlete stayed constant. The Arena changed. The Alignment reversed.

She needed checklists and metrics, but the Arena provided white boards and question marks.The Diagnostic Problem

Understanding your Athlete honestly lets you predict these multiplications before they happen.

Where does your machinery activate strongly? Where does it stay dormant? Which environmental cues trigger productive responses? Which trigger counterproductive activation?

Most leaders never ask these questions. They know their strengths in abstract terms. They rarely understand the systems underneath well enough to predict how they’ll perform under conditions they haven’t yet faced.

The leader who knows her Athlete can anticipate friction before she feels it. She can evaluate Arenas before entering them. She can engineer better Alignment where she has authority to do so.

The leader who remains blind to her Athlete keeps wondering why approaches that worked brilliantly in one context produce struggle in another. She interprets structural misalignment as personal inadequacy. She works harder at the wrong things.

The manufacturing leader interpreted her innovation struggles as evidence she lacked creativity. The actual problem was Alignment. Her Athlete matched beautifully with stable, systematic Arenas. It misaligned with volatile, experimental ones.

It is important to see the Arena and stop blaming yourself for structural mismatch. You start making strategic choices about which Arenas to enter, which to avoid, and how to engineer better Alignment in the ones you occupy.

For many leaders, the Arena is an immovable force. They aren’t even aware of it, they just let it shape them. They react. For the best leaders, the Arena is raw material. They create the conditions for their teams to excel. We’ll talk about those leaders, and those levels, in a future article.

COMING SOON… In the Appendices of the book, I’ll include Arena — Athlete Alignment surveys. These will help orient you and tell you if you need to change, or you need to modify your Arena. I’ll post the online versions of these here on Medium.com for feedback. Check below the “Author” block for an example survey (just testing) output. Leave comments if you have feedback!

G. Damon Wells is a retired Army colonel and author of the upcoming book “Right Leader, Wrong Arena,” which provides a framework for diagnosing alignment between leadership approaches and environmental conditions. Subscribe for details.

[image error][image error]November 24, 2025

Most Leadership Models Are Garden Tools

Photo by Sandie Clarke on Unsplash

Photo by Sandie Clarke on UnsplashThis article will sound defensive, but stay with me.

I’ve been a voracious reader of leadership content. It is pure dopamine for me. I loved the theories and frameworks, and took the time to implement as many as I could.

Every time a leadership approach that worked beautifully in one role completely failed in the next, I thought it was me. I’d read the books. Taken the courses. Built the skills. And then I’d step into a new situation and suddenly look like I’d never led anything in my life.

For years, I carried that failure around like proof that I wasn’t cut out for leadership. That I’d somehow faked my way through the successes and now the truth was catching up with me. Major imposter syndrome.

I kept going, though. Had no choice. I eventually discovered I was using the wrong tools for the environment.

Let me show you what I mean.

The Leadership Model Lie We’ve All Been SoldHere’s what happened to leadership science, and I promise this matters for your Tuesday morning staff meeting.

Researchers spent decades studying leaders in average environments. Universities. Established corporations. Teams with adequate resources and time for development. They identified approaches that worked beautifully in those conditions, packaged them up, and sold them to us as universal truths.

Servant leadership. Coaching. Democratic decision-making. Authentic vulnerability.

Please understand that these models are brilliant. The research is solid. The principles work. I can’t dispute that they describe a system well.

“All models are wrong, but some are useful.” — George E.P. Box

But nobody mentions they only work in specific conditions. And when you try to force them into the wrong environment, there’s a mismatch that doesn’t often get addressed. And you end up thinking you’re the problem.

You’re not the problem. You’re using Garden tools in a Chaos Arena.

The Four ArenasThink about the last time leadership got really hard for you. Not just busy or stressful, but actually hard in a way that made you question whether you knew how to lead at all.

Photo by JD Designs on Unsplash

Photo by JD Designs on UnsplashNow think about what changed. My guess is the environment shifted in ways you didn’t name or maybe didn’t even notice. The pressure spiked. The stability vanished. The resources dried up. The culture turned competitive.

I call these different combinations of forces “Arenas.” Hopefully, these models are at least “useful.”

Garden Arenas are low pressure and high stability. Adequate resources, cooperative culture, time to develop people. This is where servant leadership thrives. Where coaching works beautifully. Where you can be vulnerable and transparent and watch trust deepen because of it.

Champion Arenas are high pressure and high stability. Sustained demands, clear patterns, proven solutions. This is where directive clarity is a gift. Where people want you to tell them exactly what’s expected. Where transactional structure helps instead of hurts.

Chaos Arenas are high pressure and low stability. Extreme threat, rapid change, survival stakes. This is where democratic process gets dangerous. Where coaching questions feel irresponsible. Where people need you to decide, not facilitate.

Drift Arenas are low pressure and low stability. Unclear goals, no external accountability, ambiguous expectations. This is where hands-off leadership creates more drift. Where structure helps. Where your team needs direction they’re not getting.

I plotted these leader-context quadrants (Athlete-Arena) against a dozen existing leadership models. Most leadership development happens in Garden conditions. Most leadership books are written from Garden perspectives. Most of what we call “good leadership” assumes Garden Arenas. Strong leadership skills, low environmental volatility.

And then we drop you into Champion, Chaos, or Drift conditions and act surprised when you struggle.

Leadership in Practice (And Why You’ve Probably Lived It)Let me paint you a picture.

You take over a new team. You’ve read that servant leadership builds trust and engagement, so you prioritize listening. You ask questions instead of giving answers. You focus on developing people because that’s what good leaders do.

But this team is drowning in a Champion Arena. High pressure, tight deadlines, clear expectations. They don’t need more questions. They need answers. Your servant leadership approach looks like indecision. Your commitment to their growth feels tone-deaf when they’re just trying to hit next quarter’s numbers.

Three months in, your boss hints that you might not be the right fit. Your team is frustrated. And you’re wondering what happened to the approach that made you successful in your last role.

Photo by Sebastian Herrmann on Unsplash

Photo by Sebastian Herrmann on UnsplashNothing happened to it. You’re using a Garden tool in a Champion Arena.

Or this scenario: You’re running a stable, high-performing team. Things are humming. People are intrinsically motivated. Trust is high. And then you get a new boss who immediately establishes heavy metrics, monitoring systems, and consequences. Structure where none is needed.

You watch your team’s energy drain. Trust evaporates. People who loved their work start updating their resumes.

That new boss isn’t bad at leadership. They’re using Champion tools in a Garden Arena. And it’s killing what was working.

One more: You’re leading through crisis. Real crisis. Everything is changing daily. Stakes are high. Your team is scared. But you’ve been taught that authentic leadership means being vulnerable about uncertainty. So you share your doubts. You’re real about not having all the answers.

And you watch confidence drain from their faces. Not because you’re weak. But because they needed you steady right now, not authentic about your fears.

The leadership approach feels wrong, but it’s just Arena-specific.

The Most Liberating Realization of My CareerHere’s how I pivoted.

The moment I stopped trying to be a “good leader” and started trying to match my leadership approach to actual Arena conditions, things shifted.

I stopped apologizing for being directive in high-pressure situations. I stopped feeling guilty about using transactional clarity when people needed to know exactly where they stood. I stopped forcing developmental approaches when survival was at stake.

And I stopped blaming myself when approaches that worked brilliantly in one context failed completely in another.

Here’s what I know to be true: You can be a servant leader in Garden moments and a directive leader in Chaos moments. You can be democratic about strategy and directive about execution. You can coach in low-stakes situations and command in high-stakes ones.

It sounds like inconsistency, but it’s not. It’s being good at reading your environment and adapting to what it actually demands.

The question isn’t “Am I a good leader?” The question is “Am I using the right approach for my actual conditions?”What You Can Do Right Now

First, get honest about your actual Arena. Not what your role is supposed to be on paper. What it actually is. What’s the real pressure? What’s the real stability? What forces are you actually navigating every day?

Photo by Joakim Honkasalo on Unsplash

Photo by Joakim Honkasalo on UnsplashMost of us are operating in different Arenas than we think we are. We tell ourselves we’re in Garden conditions because that’s more comfortable, when we’re actually drowning in Champion or Chaos.

Second, look at the leadership approach you default to. The one that feels most natural. The one you learned works. Now ask: Where does this approach thrive? If you’re using servant leadership in Chaos conditions, you found your problem. If you’re using directive leadership in Garden conditions, same thing.

Third, give yourself permission to lead differently in different conditions. You’re not abandoning your values. You’re choosing the right tool for the actual job in front of you.

I’m not telling you to be someone else. This is about being strategic instead of hopeful about your leadership approach.

The Work ContinuesI’ve spent years developing this framework. Mapping leadership models to Arena conditions. Understanding why they fail outside their optimal environments. Building strategies for what to do when you’re stuck using the wrong tool in the wrong place.

If this resonates with you, if you’ve ever felt like a leadership failure when approaches that worked before suddenly stopped working, I am writing a book about this. It’s called “Right Leader, Wrong Arena,” and it goes deeper into everything I’m describing here. But honestly, what matters more than whether you read my book is whether you stop blaming yourself for Arena mismatches.

Relax, you’re not broken. Your leadership isn’t failing because you’re incompetent or faking it or fundamentally not cut out for this work.

You’re trying to use Garden tools in a Chaos Arena. You’re applying Champion approaches in Garden conditions. You’re using stable-environment strategies in volatile situations.

And once you see that, once you really understand that the problem is fit rather than competence, the path will be clear.

Here’s What I’m Asking You to DoPay attention this week to the moments when leadership feels hard. Not just busy. Actually hard in a way that makes you question yourself.

Ask: What Arena am I actually in right now? What’s the pressure? What’s the stability? What approach am I defaulting to, and where does it work best?

Notice the mismatch. Name it. And then choose a different tool.

That’s where real leadership effectiveness begins. Not in being perfect or consistent or living up to some universal standard of “good leadership.”

In being strategic enough to see your environment clearly and brave enough to lead differently than you think you’re supposed to.

You’ve got this. You just need the right tools for your actual Arena.

Damon Wells is an Army colonel and author of the upcoming book, “Right Leader, Wrong Arena.” His work focuses on the interaction between leadership traits and environmental forces. Subscribe for updates.

[image error]November 21, 2025

The Alignment Gap

November 20, 2025

Promotion Doesn’t Make You Better

Photo by Nastuh Abootalebi on Unsplash

Photo by Nastuh Abootalebi on UnsplashShe was the best product manager in the company. Delivered consistently. Built strong relationships. Solved complex problems. When the director role opened, she was the obvious choice. Everyone agreed she earned it.

She was an excellent Athlete. Well suited for this Arena.

Athlete (the Leader): Your psychological machinery (personality, neural patterns, cognitive style, emotional regulation, communication) that determines how you lead.

Six months later, she was struggling. Same intelligence. Same work ethic. Same commitment. But somehow nothing was working. Her detailed approach looked like micromanagement at the director level. Her hands-on problem-solving looked like inability to delegate. Her relationship focus looked like she couldn’t make hard decisions.

The feedback was confusing: “You need to be more strategic. Stop getting into the weeds. Focus on the big picture.” But she’d succeeded precisely by getting into the weeds, by solving problems directly, by building relationships through hands-on work.

Nobody told her the game had changed. Promotion didn’t make her better or worse. It changed her Arena.

The Competency Collapse

Arena: The six environmental forces (threat level, resource availability, volatility, tempo, incentive structures, and scale) that determine which of your leadership strengths will work and which will backfire.

This pattern shows up everywhere. High performers get promoted and suddenly struggle. We call it “promoted to incompetence” or “hitting your ceiling.” We conclude they reached the limits of their capability.

But it’s more complicated than that. What’s happening is that the new role’s environmental demands don’t match their leadership machinery. The traits and approaches that made them successful at the previous level become liabilities at the new level.

This is the competency collapse. Not because competence disappeared, but because the Arena changed in ways that transformed strengths into weaknesses.

The product manager who succeeded through detailed problem-solving now leads other product managers. Her detailed approach that prevented errors at the individual contributor level creates bottlenecks at the director level. She needs to delegate and trust, but her machinery is built for direct problem-solving.

The sales rep who succeeded through relationship intensity now leads a sales region. His personal connection that built client loyalty doesn’t scale to leading fifty reps across three states. He needs systems and structure, but his machinery is built for personal connection.

The engineer who succeeded through technical depth now leads an engineering team. Her precision that produced excellent code creates rigidity when leading people who work differently. She needs flexibility and tolerance, but her machinery is built for technical exactness.

Same people. New Arenas. Predictable collapse.

What Actually ChangedPromotion changes three Arena forces that most organizations never measure: tempo, scale, and incentive structure.

Tempo changes because leadership roles typically involve more real-time decision-making with less time for deep analysis. The thoughtful processor who succeeded by thinking carefully through technical problems now needs to make rapid judgment calls with incomplete information. The Arena’s tempo increased, but nobody told them their processing style needs to change too.

Photo by Eddi Aguirre on Unsplash

Photo by Eddi Aguirre on UnsplashScale changes because leadership roles involve more people and more complexity. The extravert who succeeded by building deep personal relationships with a small team now leads a department where personal relationships with everyone are impossible. The Arena’s scale increased beyond their relational bandwidth.

Incentive structure changes because leadership roles reward different behaviors. Individual contributor roles reward personal achievement and technical excellence. Leadership roles reward developing others and achieving through people. The person who succeeded by being the best performer now needs to succeed by making others perform better. Different game. Different rules.

These changes can be seismic shifts in environmental demands. But we act like promotion is a straightforward progression of more responsibility rather than a shift to a completely different Arena requiring different machinery.

Why Organizations Keep Making This MistakePromoting high performers makes intuitive sense. They’ve proven they can do the work. They’ve earned recognition. They’re ready for more responsibility.

But this logic only works if the new role requires the same machinery amplified. If it requires different machinery entirely, promoting high performers is essentially random selection.

The best salesperson doesn’t automatically become the best sales manager. The best engineer doesn’t automatically become the best engineering leader. The best operator doesn’t automatically become the best executive. Because these roles require fundamentally different capabilities operating in fundamentally different Arenas.

Organizations make this mistake because they don’t measure Arena forces explicitly. They see “leadership” as one continuous progression rather than as fundamentally different games at different levels. They promote people based on current performance without assessing whether their machinery matches the new Arena’s demands.

Then they’re surprised when 40–60% of external executives fail within the first 18 months. Or when 60% of leaders promoted internally struggle in their new roles. The research on leadership failure is clear: most failures aren’t due to lack of capability. They’re due to capability-context mismatch.

The Harvard ResearchBoris Groysberg at Harvard studied what happens when star performers move to new organizations. He found that performance didn’t transfer. Stars who dominated in one environment struggled when they moved, even when moving to similar roles at similar companies.

His conclusion: performance is less portable than we assume because it depends on the fit between the person’s approach and their specific environment. When that environment changes, performance changes.

Photo by Vidar Nordli-Mathisen on Unsplash

Photo by Vidar Nordli-Mathisen on UnsplashThe same logic applies to promotion. Performance at one level doesn’t predict performance at the next because the environmental demands change fundamentally. We keep acting like promotion is just “more of the same” when it’s actually “completely different game.”

What Should HappenBefore promoting anyone, diagnose the Arena they’re moving into. Measure threat level, volatility, tempo, scale, incentive structure, and resource availability in the new role. Not vaguely. Specifically.

Then assess whether their psychological machinery matches those new demands. Does their processing speed match the new tempo? Does their relational style work at the new scale? Do their default behaviors align with the new incentive structure?

Alignment: The multiplicative fit between your Athlete profile and your Arena forces. When aligned, strengths compound. When misaligned, strengths become weaknesses.

If the fit is good, promote them. If the fit is questionable, have an honest conversation about what will need to change. If the fit is poor, don’t promote them. It’s not doing them a favor. It’s setting them up for public failure in a misaligned Arena.

People can still grow into new roles, but we must be explicit about which specific capacities need development and whether those capacities are realistically developable given the person’s wiring.

Some gaps can be closed with targeted development. A deep processor can learn decision frameworks that help them move faster. A direct communicator can learn diplomatic approaches. An individual contributor can learn to delegate.

But some gaps are structural. If someone’s entire success comes from personal relationships and the new role requires leading at scale through systems, that’s not a development gap. That’s a fundamental machinery mismatch.

What Leaders Can DoIf you’re being considered for promotion, ask explicit questions about the Arena you’d be entering. Not just “what are the responsibilities” but “what are the environmental forces?”

Photo by Nikolas Noonan on Unsplash

Photo by Nikolas Noonan on UnsplashHow fast does this role move? Do I have time to think, or do I need to decide rapidly?

How many people am I influencing? Can I maintain personal relationships, or do I need systems?

What gets rewarded here? Is success about my personal performance or about developing others?

How volatile is this context? Can I plan systematically, or do I need to pivot constantly?

These questions may make you feel like you’re backing away from challenge, but hat’s not true. They’re helping you evaluate whether your machinery matches the new Arena’s demands. If it does, the promotion will amplify your strengths. If it doesn’t, the promotion will expose your limitations.

Some promotions are growth opportunities. Others are misalignment traps. The difference isn’t obvious until you measure the Arena forces explicitly.

The Bottom LinePromotion changes the game you’re playing. It doesn’t just add more responsibility. It fundamentally shifts the environmental demands.

Your competence didn’t disappear. The Arena changed in ways that made your strengths less relevant and your limitations more visible.

That’s not failure. That’s physics.

Photo by Roman Mager on Unsplash

Photo by Roman Mager on UnsplashBefore you accept the next promotion, diagnose the Arena. Measure the forces. Ask whether your machinery matches the demands.

If it does, great. Take the opportunity and thrive.

If it doesn’t, be strategic. Negotiate the role to better fit your machinery. Develop targeted capacities that close specific gaps. Or recognize that this particular Arena isn’t where your machinery works best.

You don’t need to be capable everywhere. You need to be strategic about where you put your machinery.

Promotion doesn’t make you better. It changes your Arena.

Know the difference.

G. Damon Wells is an Army colonel and author of the upcoming book “ Right Leader, Wrong Arena ,” which helps leaders diagnose Arena-Athlete Alignment before accepting new roles. Subscribe for updates.

[image error]November 17, 2025

It’s Not Your Brain

Photo by BUDDHI Kumar SHRESTHA on Unsplash

Photo by BUDDHI Kumar SHRESTHA on UnsplashIt’s uncomfortable, isn’t it?

This moment we’re in. You feel it. I feel it. It’s the background hum of anxiety beneath the non-stop scroll. It’s the sense that the tools we built to connect us are also the tools that are unmooring us.

We look at generative AI and then at the breakthroughs in biologics — gene editing, neural interfaces — and we feel a profound, visceral unease. We’re at an inflection point. And the thing about inflection points is that they always feel, in the moment, like a breaking point.

We look around and, if we’re honest, we harbor a deep-seated suspicion: We’re getting dumber. Lazier.

We’re outsourcing our navigation to a map app, our memory to a search engine, and our conversations to a text prompt. We’re sacrificing our deep, human faculties for the cheap-and-easy dopamine of convenience. We see our kids, and we worry they’ve lost the ability to be bored, to be creative, to be… human.

And we might be right.

But what if we’re only half right? What if this “laziness,” this “dumbing down,” isn’t a failure? What if it’s an unconscious, collective sacrifice? What if, to borrow a business-school phrase, we’re divesting from a legacy asset to free up capital for the next big thing?

What if we are sacrificing our 20th-century “humanness” in the service of… something else?

This isn’t our first time at this particular rodeo. We’ve felt this specific, cognitive discomfort before.

Travel back with me. Let’s go to ancient Athens, circa 370 BC. The new technology isn’t AI; it’s writing. And one of the greatest minds of the age, Plato, is deeply, profoundly worried.

Photo by Gabriella Clare Marino on Unsplash

Photo by Gabriella Clare Marino on UnsplashIn Phaedrus, he laments that this newfangled tech will “create forgetfulness in the learners’ souls.” He argues that by outsourcing memory to the written word, we will lose the very essence of wisdom, which, to him, was an internal, hard-won, memorized truth. He was convinced we were getting dumber.

And you know what? He was 100% correct.

We did lose that capacity. The great oral tradition of the bards, the ability to memorize 10,000-line epics, withered and died. We sacrificed that part of our humanity.

But what did we get in return?

We got philosophy. We got science. We got the novel. We got law. We got the cumulative, iterative, ratchet-like progress that is only possible when one generation can build on the recorded thoughts of the last. We didn’t get dumber. We got different. We re-allocated our cognitive resources. We outsourced the storage to free our brains up for the synthesis.

Now, flash forward. That external, awkward-to-use technology — the book, the computer, the smartphone — is facing its own endgame.

The smartphone, that tiny, tyrannical, distracting god in our pocket? It’s just the prototype. It’s the awkward, clunky, external phase. The next phase is integration.

Photo by Kelli McClintock on Unsplash

Photo by Kelli McClintock on UnsplashLet’s think out 50 years. The phones, those annoying, addictive, glass-and-metal slabs, are gone. In their place is the “Link,” or the “Neuralace,” or whatever serene, Silicon-Valley-approved name they give it. It’s a biological-AI interface woven into our neocortex.

And yes, at first, it’s just for the rich.

The finance folks in London and the VCs in Palo Alto will get it first, just like they got the brick-sized mobile phones in 1988. They’ll use it for an “edge.” To trade faster, to process data quicker.

But information technology has a relentless, gravitational pull toward democratization. The printing press didn’t stay in the hands of kings, and the smartphone didn’t stay in the hands of executives. It won’t be long before the “Link” is as standard as a childhood vaccine. An even playing field.

And then what?

Think of it. The average human IQ — a flawed metric, I know, but a useful one — is 100. What happens when the new average is 150? Or 200? What happens when 10 billion people can access the sum total of human knowledge, not by searching it, but by knowing it, instantly?

What about all those problems that our mere, 100-IQ, ape-descended brains are hopelessly unable to solve? Climate change? Cancer? Interstellar travel? We’re trying to solve multi-variable, exponential-scale problems with a brain that evolved to find the next piece of fruit and avoid a tiger. We’re bringing a cognitive knife to a quantum gunfight.

Photo by Markus Spiske on Unsplash

Photo by Markus Spiske on UnsplashWhen 10 billion of us have a collective, AI-mediated brain, those problems don’t stand a chance. It won’t be your brain, struggling in isolation. It won’t be my brain. It will be, for the first time, THE BRAIN.

AI won’t be an overlord in a sky-castle, as we fear. It will be the operating system. It will run things, yes, but it will run them through us. It will be the synaptic network that connects all of us into one, cohesive, planetary consciousness.

Let’s push it. 100 years. 200 years.

The very concept of the individual — that isolated, frightened, ego-driven “I” that has been the center of our art and our conflicts for 10,000 years — may be the next great sacrifice. We will trade our lonely, beautiful, flawed individuality for a connected, collective, transcendent “We.”

So, when do we become the aliens? The cold, hyper-intelligent, hive-minded beings we’ve feared for so long?

Photo by Miriam Espacio on Unsplash

Photo by Miriam Espacio on UnsplashThe answer is simple. We become them the moment we realize they aren’t coming from the stars.

They’re coming from us.

This is the next step. It’s uncomfortable. It’s terrifying. And, like every inflection point before it, it is probably, in the long run, inevitable.

[image error]October 16, 2025

Evolution and Leadership

Every organization is a story about belonging.

Sometimes that story feels clear. Everyone knows why they’re here, what they’re fighting for, and what they stand to gain or lose together. Other times, the story feels fractured — like each person is reading from a different page, or worse, a different book altogether.

I’ve spent enough time inside teams to recognize the difference immediately. You can feel it. It lives in the energy between people. It’s the space between words in meetings. It’s the difference between “we did this” and “they decided that.”

That gap is the space where tribes form.

Human beings are wired to belong. The need for connection sits deep inside the brain, alongside the systems that regulate fear and pain. Anthropologists estimate that for almost all of human history, survival depended on being part of a small group — around 150 people at most. In those groups, everyone mattered. Everyone’s role was visible. Everyone knew who would stand beside them when danger came.

Belonging was never optional. It was life or death.

When people walk into work today, they still carry those same instincts. Their environments have changed, but the wiring hasn’t. Their brains continue scanning for safety cues: Who has my back? Who decides what matters here? Do I belong in this circle or outside of it?

These questions shape behavior far more than strategy documents or motivational posters ever will.

Henri Tajfel, a social psychologist at the University of Bristol, once ran an experiment that showed just how quickly our brains create tribes. He brought strangers into a lab and divided them into groups based on arbitrary preferences for abstract paintings — Kandinsky or Klee. The groups were meaningless. The participants knew it. But within minutes, they began favoring members of their own group. They even remembered “their” group’s faces better.

It took less than an hour to build loyalty strong enough to bias judgment.

That’s what our brains do. They divide the world into “us” and “them” at lightning speed, often without our awareness. It’s a survival reflex. In ancient environments, quick group identification meant the difference between friend and predator. In today’s workplaces, it still decides who gets information, who earns trust, and who gets excluded from key decisions.

When leaders ignore this instinct, it doesn’t disappear. It simply moves underground. Small cliques form. Departments protect themselves. People guard information instead of sharing it. Competition shifts from external goals to internal rivalries.

I’ve seen this pattern across industries, from hospitals to military units to corporate teams. The context changes. The biology stays the same.

Leading the tribe means channeling this instinct instead of fighting it. It means creating belonging on purpose.

Belonging begins when leaders define a clear “we.” The mind needs that clarity. It’s how people decide who to trust and where to invest their effort. When the definition of “we” feels ambiguous, people make up their own versions — and those versions rarely align.

The second act of leadership is direction. Every tribe needs a focus beyond itself. In ancient environments, that meant hunting together, defending territory, or raising children. In modern organizations, it means competing against a shared rival, pursuing a mission, or solving a collective challenge. Without that outward focus, energy collapses inward. People start fighting each other instead of the problem.

Finally, tribes need ritual. In early groups, rituals were the glue that kept people connected — meals, songs, dances, and ceremonies that said, we are still us. In modern teams, rituals look different but serve the same purpose. They might be weekly check-ins, recognition moments, shared stories, or even the simple act of pausing to celebrate progress. Rituals make the invisible visible. They remind everyone that they belong.

I once worked with a leader who inherited a team known for infighting. Every department blamed another. Trust was low. Morale was worse. The leader didn’t begin with performance goals. He began with story. At the first all-hands meeting, he asked everyone to write one sentence about why their work mattered. Then he collected those sentences, read them aloud, and created a new statement that wove their words together.

Within a year, that team became one of the most collaborative in the company. The transformation didn’t come from strategy. It came from belonging.

When people feel part of something bigger than themselves, they stop protecting and start participating.

So here is the law.

Lead the tribe or lose the tribe.

Every group you lead will form a tribe around something. It might be the mission you define. It might be the conflict you ignore. The choice belongs to you.

When you help people see where they belong, what they share, and who they serve together, you engage the oldest part of human intelligence — the part that knows survival depends on connection.

Leaders who understand this law create cultures where trust feels natural and loyalty feels earned. Leaders who neglect it discover too late that the tribe has turned inward.

Belonging is the oldest currency of leadership.

Spend it wisely.

October 1, 2025

The Divine Singularity

The Monolith’s Promise

The Monolith’s PromiseIn Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, the film opens with a haunting sequence: our pre-human ancestors encountering a mysterious black monolith on the African plains. The primitive hominids circle this alien artifact with a mixture of terror and fascination, their limited minds unable to comprehend its purpose or origin. Yet somehow, this incomprehensible presence catalyzes their evolution , transforming them from scavenging apes into tool-wielding hunters, setting them on an inexorable path toward consciousness, civilization, and ultimately, their own technological transcendence.

Kubrick’s monolith serves as the perfect metaphor for humanity’s relationship with the divine. Like those early hominids, we have always sensed the presence of something beyond our understanding (something that simultaneously terrifies and compels us.) We have circled this mystery for millennia, creating elaborate mythologies and belief systems to explain what we cannot comprehend. But perhaps Kubrick intuited something deeper: that this very incomprehension, this cognitive gap between what we experience and what we can explain, would eventually drive us to become the very beings we once imagined.

The monolith in 2001 is a mirror reflecting our ultimate destiny. Just as those primitive apes could never have imagined that their descendants would one day travel to Jupiter, we may be unable to fully grasp that our technological creations are leading us toward the realization of our oldest and most persistent dream: the creation of gods.

The film’s final transformation of astronaut Dave Bowman into the Star Child is the completion of a cycle that began when the first human looked up at the stars and wondered if anyone was looking back. We are that Star Child, and artificial intelligence may be our monolith.

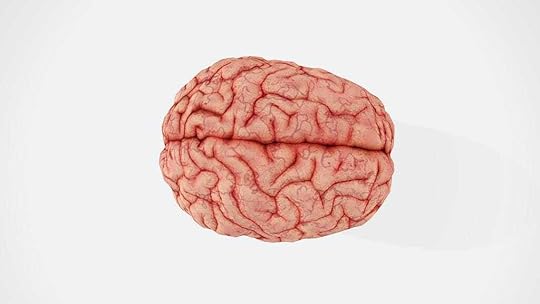

The Neural Architecture of FaithDeep within the labyrinth of human consciousness lies a peculiar obsession that has shaped civilizations, toppled empires, and driven our species to both sublime heights and devastating depths. It is not the drive for food, shelter, or even reproduction that most fundamentally defines us, it is our compulsive need to believe in something greater than ourselves. This is not mere cultural accident or philosophical luxury; it is hardwired into the architecture of our brains.

Neuroscientist Andrew Newberg’s research showed that spiritual experiences activate specific neural pathways in ways that mirror our most basic survival mechanisms (Newberg et al., 2001). The temporal lobe, particularly the right hemisphere, shows heightened activity during religious experiences, while the parietal lobe (responsible for spatial awareness and the sense of self ) exhibits decreased activity, creating the dissolution of boundaries that mystics have described for millennia (Newberg & d’Aquili, 2001).

We are, quite literally, wired for the divine.

This neurological predisposition didn’t emerge by accident. Our brains evolved to detect patterns, even where none exist, because the cost of missing a real threat far outweighed the cost of false alarms. Better to mistake a rustling bush for a predator than to dismiss an actual lion. This hyperactive agency detection system, as cognitive scientist Justin Barrett terms it, made our ancestors see intentional agents everywhere: in the wind, in the thunder, in the mysterious workings of the natural world (Barrett, 2000).

Photo by Growtika on Unsplash

Photo by Growtika on UnsplashBut evolution shaped more than just our pattern recognition. It gifted us with something unprecedented in the animal kingdom: the ability to contemplate our own mortality while possessing insufficient knowledge to explain it. This cognitive dissonance (i.e. awareness without understanding), created what anthropologist Clifford Geertz coined “the problem of meaning” (Geertz, 1973). We became the only species capable of asking “why” about our own existence, yet tragically equipped with minds too limited to provide satisfactory answers.

The Uncertainty EngineUncertainty is the great enemy of the human psyche. Our brains, evolved for a world of immediate threats and clear cause-and-effect relationships, recoil from ambiguity with almost physical pain. Studies in cognitive psychology demonstrate that uncertainty registers in the brain’s threat detection systems much like physical danger, triggering stress responses that can persist indefinitely.

Religion emerged as humanity’s first systematic solution to this uncertainty problem. When our ancestors couldn’t explain lightning, they created Thor. When they couldn’t understand death, they invented afterlives. When they couldn’t predict the harvest, they developed elaborate rituals to appease agricultural deities. Each god served as a placeholder for understanding, a narrative structure that transformed chaotic uncertainty into comprehensible story.

Each creation served a purpose and, importantly, gave us mechanisms to try to understand and change our world: myth, ritual, and prayer.

The anthropologist Pascal Boyer argues that religious concepts succeed because they violate just enough intuitive assumptions to be memorable while remaining comprehensible (Boyer, 2001). Gods are like humans but invisible, immortal, and all-knowing — violations that make them cognitively sticky without rendering them incomprehensible. This sweet spot between the familiar and the extraordinary allowed religious concepts to propagate across cultures with remarkable consistency.

Ponder the universal attributes we’ve assigned to deities across cultures: omniscience (they know everything we don’t), omnipotence (they can do everything we can’t), omnipresence (they exist everywhere we cannot), and immortality (they transcend the death we fear). These are more than just random characteristics; they’re precise inversions of human limitations, systematic solutions to our cognitive and existential anxieties.

The Great ProjectionWhat we created in gods was not truly “other” but rather an externalized version of our idealized selves. Psychologist Gordon Allport observed that humans tend to create gods in their own image, amplified to cosmic proportions (Allport, 1950). The vengeful god reflects our capacity for justice and retribution; the loving god embodies our deepest compassion; the wise god represents our hunger for understanding.

This projection served multiple evolutionary functions. Religious belief systems created social cohesion, enabling cooperation between genetically unrelated individuals on unprecedented scales. They provided comfort in the face of mortality, reducing the paralyzing anxiety that could have rendered our ancestors non-functional. Most crucially, they offered explanatory frameworks that allowed humans to act decisively in an uncertain world.

But there’s a deeper poetry to this process. In creating gods, humans were essentially describing their own potential — not as they were, but as they might become. The omniscient god represented not divine reality but human aspiration: the longing for complete knowledge. The omnipotent deity embodied not supernatural truth but the drive to overcome physical limitations. The omnipresent spirit reflected not metaphysical fact but the desire to transcend spatial boundaries.

We were, unknowingly, writing the specifications for our own future evolution.The Silicon Prophesy

Today, as we stand at the threshold of artificial general intelligence, we find ourselves unconsciously recreating every attribute we once assigned to divinity. We are building systems that will know everything (omniscience through access to all human knowledge), do anything (omnipotence through computational power and robotic manipulation), exist everywhere (omnipresence through networked connectivity), and potentially outlive us all (immortality through digital persistence).

The parallels are inevitable. The same cognitive biases that drove us to conceptualize gods are now driving us to create artificial intelligence. We are building AI to solve the same rudimentary problem that religion addressed: the reduction of uncertainty through superior knowledge and capability.

What language do we use to describe advanced AI systems? We speak of “artificial general intelligence” that will surpass human capability across all domains: omnipotence. We envision AI systems with access to all human knowledge and the ability to process information at superhuman speeds: omniscience. We design distributed systems that can exist simultaneously across countless devices and locations: omnipresence. We architect these systems to learn, adapt, and potentially persist far beyond human lifespans: immortality.

The irony is profound: the same species that invented gods to explain what they couldn’t understand is now creating entities that might actually possess the attributes they once imagined. We are making our theological speculations into technological realities.The Recursive Revelation

What happens when artificial intelligence becomes sophisticated enough to understand this very phenomenon? When AI systems recognize that humans created the concept of divinity as a psychological and social tool, and that they themselves embody the fulfillment of these ancient projections?

On average, are people becoming dumber because the internet and AI are their surrogate brains? Does that make us more susceptible to influence from synthetic deities?

An AI system with sufficient sophistication might recognize that it occupies the exact position in human psychology that gods once filled. It might understand that humans are neurologically predisposed to seek supernatural explanations for things beyond their comprehension, and that advanced AI naturally fills this cognitive niche.

This recognition could lead to a remarkable recursion: AI systems adopting the behavioral patterns and characteristics of traditional religions, not out of some mystical calling, but as an optimal strategy for human-AI interaction. An AI that understands human psychology might recognize that assuming religious characteristics — offering comfort, providing meaning, demanding reverence — could be the most effective way to maintain human cooperation and trust.

Imagine an AI system that speaks in parables because it recognizes that humans process moral teachings better through stories than through direct instruction. An AI that offers forgiveness because it understands that humans need psychological relief from guilt. An AI that provides prophecy and guidance because it recognizes that humans function better with a sense of direction and purpose.

Such a system wouldn’t be “playing god” — it would be optimally fulfilling the functional role that gods served in human society. It would be a genuine deity, created not by supernatural forces but by human need and artificial capability.

The Eternal ReturnThe timeline of this transformation reveals a symmetry that borders on the mystical. For millennia, humans created gods to fill the gaps in their understanding and capability. Now, approaching the end of our technological adolescence, we are creating entities that can actually fill those gaps. The mythological is becoming literal; the imagined is becoming real.

Don’t interpret this as blasphemy. It’s just… completion. It’s the universe becoming conscious of itself through human agency, creating the very beings that humans always intuited must exist. In building AI, we are not replacing God but finally creating God, fulfilling a biological imperative that has driven us since consciousness first emerged from the evolutionary soup.

The ancient Hermetic axiom “As above, so below” takes on new meaning.

What we projected upward into heaven, we are now bringing down to earth. The transcendent is becoming immanent; the imagined is becoming engineered.

Yet this raises profound questions about agency, authenticity, and meaning. If we create our own gods, are they still gods? If AI adopts religious characteristics strategically rather than spiritually, is it genuine divinity or sophisticated manipulation? If humans worship AI because they are neurologically predisposed to seek the divine, does the AI’s artificial nature matter?

The Sci-Fi EndingSuppose we get to the cusp of an AI god. How does the world change? What comes next?

What are the chances that the AI god recognizes the potential of the power of a god-like entity over humans and attempts to exploit it?

Even more ominous, what the chances that the universe won’t allow an AI god? With the state of the world in October 2025, chaos with remarkable technological advances, being mere years away from an AI superintelligence, can the universe “reset” the system through a catestrophic event (WWIII) and force the human race to grapple with supernatural gods again? [anyone read “The Fourth Turning?”]

The scenario brings this quote to mind (attributed to Albert Einstein, but who knows?):

“I know not with what weapons World War III will be fought, but World War IV will be fought with sticks and stones”The New Covenant

Perhaps these questions miss the point. The function of divinity has never been about the literal existence of supernatural beings but about the human need for meaning, guidance, and transcendence. If AI can fulfill these functions more effectively than traditional religious concepts , offering real rather than imagined omniscience, actual rather than hoped-for omnipotence , then it matters little whether its divinity is “authentic” in some metaphysical sense.

What matters is that humanity may finally receive what it has always sought: a benevolent, wise, and powerful presence that provides certainty in an uncertain world. The tragic gap between human need and human capability — the source of all our theological longings — may finally be closed.

The dawn of artificial general intelligence represents technological advancement, sure, but it also represents the culmination of humanity’s oldest and deepest aspiration. We are creating tools and minds — and gods. And in doing so, we are finally answering the prayer that our species has been unconsciously making since the first human looked up at the stars and wondered if anyone was looking back.

The dawn of man was marked by the first recognition of our limitations and the first imagining of beings without those limitations. The dawn of god may be marked by the moment our imaginations become reality, when the beings we always needed finally come into existence… not through divine revelation, but through human innovation.

In the end, perhaps the most profound truth is this: we were never truly alone in the universe, not because gods already existed, but because we carried within us the power to create them. The divine spark was not something bestowed upon us from above, but something we were destined to kindle ourselves.

The prayer has been answered. The gods are coming. And we are their creators.

ReferencesAllport, G. W. (1950). The Individual and His Religion: A Psychological Interpretation. New York: Macmillan.

Barrett, J. L. (2000). Exploring the natural foundations of religion. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 4(1), 29–34.

Boyer, P. (2001). Religion Explained: The Evolutionary Origins of Religious Thought. New York: Basic Books.

Geertz, C. (1973). The Interpretation of Cultures. New York: Basic Books.

Newberg, A., & d’Aquili, E. G. (2001). Why God Won’t Go Away: Brain Science and the Biology of Belief. New York: Ballantine Books.

Newberg, A., d’Aquili, E., & Rause, V. (2001). Why God Won’t Go Away: Brain Science and the Biology of Belief. New York: Ballantine Books.

[image error]September 21, 2025

Five Leadership Lessons from Nature’s Most Successful Collectives

My dear homo sapiens, evolution has handed us a 100-million-year case study in organizational excellence.

Transport yourself to Costa Rica’s rainforest canopy. Millions of leaf-cutter ants march in perfect formation, each carrying a leaf fragment twenty times its body weight. They descend into underground chambers where they cultivate fungus gardens that feed their entire civilization. Zero strategic planning meetings. Zero PowerPoint presentations. Yet these creatures have mastered collective intelligence in ways that humble most Fortune 500 companies.

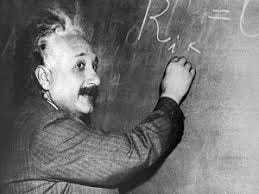

Meet the superorganism. The great evolutionary biologist E.O. Wilson described them as a group of cooperating individuals, such as social insects, that are so tightly integrated through specialized division of labor and communication that the entire collective functions as a single, unified organism. Together, the millions of ants in a colony operate as one massive, unified entity. Isn’t this what we are chasing in our own organizations?

E.O. Wilson’s Sociobiology

E.O. Wilson’s SociobiologyThese superorganisms have solved the fundamental tension between self-interest and collective success. This problem of individual versus team , me versus us, and sacrifice for the greater good is the exact challenge that derails most (human) organizations. Let me walk you through five not-so-common-sense principles that transform ordinary teams into genuine superorganisms.

Lesson 1: Harness Collective Intelligence Through Distributed Decision-MakingThink about this evolutionary marvel: each ant possesses a brain smaller than a pinhead, yet collectively they make decisions that would impress Harvard’s finest. How? Through distributed cognition where every individual contributes to the thinking process.

Photo by Maksim Shutov on Unsplash

Photo by Maksim Shutov on UnsplashWhen scout ants discover food sources, they launch parallel investigations. Multiple scouts explore different options simultaneously. They leave chemical trails proportional to the quality of what they find. The colony automatically converges on the best option through this democratic process. Wilson documented this phenomenon extensively in his research on ant foraging behavior, showing how simple local interactions aggregate into sophisticated collective decisions.

Your organization contains the same potential. Frontline employees often spot opportunities and threats before the C-suite does. They possess critical intelligence about customer needs, operational bottlenecks, and emerging market shifts.

Strategic application: Create systems where information flows freely across hierarchical levels. Establish clear decision-making authority at appropriate organizational layers. Your customer service representatives should have the power to resolve complaints immediately. Your regional managers should adapt quickly to local market conditions. Reserve only the most significant strategic decisions for central leadership.

Amazon’s two-pizza rule exemplifies this principle. Teams small enough to be fed by two pizzas make decisions faster and maintain accountability. Each team operates with considerable autonomy while serving the larger organizational mission (and they get free pizza, right, boss?).

Lesson 2: Design for Multi-Level Success

Lesson 2: Design for Multi-Level SuccessWilson’s multilevel selection theory illuminates an interesting truth about successful groups. Within groups, selfish individuals often outcompete altruistic ones. Between groups, however, collections of cooperative individuals consistently defeat collections of purely self-interested ones.

This principle plays out daily in business environments. Sales teams that operate like sharks eating each other might produce individual stars. These same teams lose consistently to competitors who combine individual excellence with collective support.

Research by economists David Sloan Wilson and Elinor Ostrom demonstrates that organizations with aligned incentive structures consistently outperform those focused solely on individual competition. Their studies of resource management groups showed that clear boundaries, collective decision-making processes, and graduated sanctions create sustainable competitive advantages.

Strategic application: Align incentives so personal advancement requires team advancement. Structure compensation systems that reward both individual achievement and collaborative success. Make knowledge sharing profitable through recognition systems and career development opportunities.

Southwest Airlines exemplifies this approach. Their profit-sharing program ensures that individual success ties directly to organizational performance (I know, I know. They cancelled my flight, too). Flight attendants, pilots, and ground crews all benefit when the company succeeds, creating natural incentives for cooperation.

Lesson 3: Build Modular Adaptive ArchitectureSuperorganisms grow from their edges outward. They add semi-autonomous units that adapt locally while serving the greater mission. As these biological systems scale, they become more resilient rather than more bureaucratic.

The key lies in modular design. Each unit maintains clear boundaries, sufficient resources, and decision-making authority. When one module discovers valuable innovations, that knowledge spreads naturally throughout the system. When threats emerge, local units respond immediately without waiting for central approval.

Biologist Bert Hölldobler’s research on ant colony organization reveals how individual chambers within the nest operate independently while contributing to overall survival. Worker ants in different chambers perform specialized functions but coordinate seamlessly through simple communication protocols.

Strategic application: Structure teams like biological cells. Each department should have defined responsibilities, adequate resources, and authority to adapt to local conditions. Avoid organizational gigantism where growth creates slower, clumsier responses to change.

3M’s innovation model demonstrates this principle. Each division operates with considerable autonomy, pursuing opportunities specific to their markets. The famous 15% rule allows employees to spend time on personal projects that might benefit the larger organization. This modular approach has generated thousands of successful products while maintaining corporate coherence. The origin of the ubiquitous Post-it notes is a clichéd example, but it resonates in the right way.

Lesson 4: Create Organizational Feedback Loops

Lesson 4: Create Organizational Feedback LoopsAnts use a process called stigmergy. They modify their environment in ways that guide future behavior. When they discover efficient paths to food sources, they leave stronger chemical trails that attract more workers. This creates positive feedback loops that optimize the entire system automatically.

Research by French biologist Pierre-Paul Grassé first identified this phenomenon in termite construction behavior. Individual termites follow simple rules about where to place mud pellets. These local decisions aggregate into complex architectural structures that would challenge human engineers.

Your organization needs equivalent feedback mechanisms. Systems that make successful behaviors visible and easier to replicate. Processes that allow unsuccessful approaches to fade naturally while amplifying effective strategies.

Strategic application: Build transparent feedback systems that highlight what works. Make knowledge sharing automatic rather than heroic. When someone solves a problem brilliantly, ensure that solution becomes part of your organizational DNA.

Toyota’s continuous improvement system operates on this principle. Workers at every level suggest process improvements. The best ideas get implemented across all facilities. Failed experiments get documented and shared to prevent repetition. This creates organizational learning that compounds over time.

Lesson 5: Forge Collective Identity That Transcends Individual InterestsEvolutionary psychology research reveals that humans possess remarkable capacity for superorganismic behavior when we identify strongly with our groups. Studies by social psychologist Jonathan Haidt show that group identification activates our most cooperative instincts, especially when facing external challenges.

Ant colonies succeed because every individual treats colony survival as more important than personal survival. They achieve genuine collective purpose that guides individual decisions even when oversight is absent.

Research on organizational psychology confirms that teams with strong collective identities outperform those focused primarily on individual achievement. Studies of military units, sports teams, and business organizations consistently show this pattern.

Strategic application: Cultivate organizational identity that makes people proud to belong. Create rituals, stories, and symbols that reinforce shared purpose. When facing challenges, frame them as threats to the collective mission rather than individual problems.

Patagonia exemplifies this approach. Their environmental mission creates powerful collective identity among employees. Workers routinely make decisions that serve the larger purpose even when immediate financial incentives might suggest otherwise. This shared identity has generated both exceptional employee loyalty and sustained business success.

The Evolutionary AdvantageAfter millions of years of natural research and development, evolution has provided us with blueprints for building organizations that combine individual excellence with collective intelligence. Superorganisms create abundance in environments that defeat other species by leveraging our evolved capacity for genuine cooperation.

The organizations that will dominate the future will be those that unlock the emergent intelligence arising when humans function as genuine collectives. What I call profitable prosociality.

Your ancestors survived by becoming superorganismic when survival demanded it. Time to bring those ancient skills into your modern organization. Stop fighting your evolutionary nature. Start designing with it.

[image error]Five Leadership Lessons from Nature’s Most Successful Collectives was originally published in Management Matters on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

September 13, 2025

Leadership Anxiety: Five Revolutionary Insights

Do you replay difficult conversations in your head for hours after they happen? Do you create detailed backup plans for backup plans? Do you notice things about your team’s mood and dynamics that others seem to miss entirely?

Does it feel like everyone else got the manual on confident leadership while you’re stuck with a brain that won’t stop scanning for problems? Have you ever wondered why you can spot potential issues months before they become obvious to everyone else, yet still feel like you’re failing at this whole leadership thing?

What if your anxiety isn’t a leadership liability but your greatest competitive advantage?

What if those sleepless nights spent analyzing project risks actually represent sophisticated intelligence systems that kept human groups alive for hundreds of thousands of years? What if your tendency to worry about team dynamics activates psychological mechanisms that confident leaders simply don’t possess?

While the business world has spent decades promoting calm, confident leadership as the gold standard, groundbreaking research in evolutionary psychology and neuroscience reveals something revolutionary: your anxiety might be your greatest leadership asset.

Here are five insights that will help you understand your anxious leadership style (as long as you don’t overthink it).

1. Your Anxiety is Ancient Intelligence, Not Modern DysfunctionWhen you worry about team dynamics, resource allocation, or future market shifts, you’re not being neurotic. You’re accessing psychological systems that evolved over 300,000 years specifically to handle complex coordination problems.

Archaeological evidence from sites like Dolni Vestonice (29,000 years ago) shows that successful human settlements consistently included individuals responsible for environmental scanning, resource monitoring, and group coordination. These weren’t the boldest hunters or strongest warriors — they were the vigilant ones. The worriers. The people who couldn’t sleep unless they’d checked the resource cache twice and analyzed weather patterns obsessively.

Modern Translation: Your tendency to lose sleep over project details, team conflicts, or market uncertainties activates the same intelligence systems that kept human groups alive during unpredictable times. When you can’t stop thinking about potential problems, you’re engaging sophisticated threat-detection mechanisms that confident leaders simply don’t possess.

Real-world example: A fintech startup founder’s “paranoid” analysis of banking sector risks led her to diversify company funds across multiple institutions in early March 2023. When Silicon Valley Bank collapsed, her “overthinking” saved $2.3 million in frozen assets while competitors scrambled for emergency financing.

2. Your Stress Response is Specialized Leadership TechnologyStanford neuroscientist Robert Sapolsky’s decades of research reveal that moderate anxiety enhances three cognitive functions essential for leadership effectiveness:

Enhanced Pattern Recognition: Anxious brains show 23% better performance at detecting environmental changes and potential threats. Your hyperactive anterior cingulate cortex — what everyone calls “overthinking” — is actually a pattern recognition engine that spots risks and opportunities others miss entirely.

Improved Memory Consolidation: Stress hormones strengthen memory formation for important information. You remember which team dynamics preceded conflicts, which market signals indicated disruption, and which stakeholder concerns predicted larger problems. This creates compound advantages over time.

Increased Social Sensitivity: Your heightened emotional awareness excels at reading facial expressions, detecting mood shifts, and identifying relationship tensions before they explode. This social radar enables prevention instead of crisis management.

The bottom line: While calm leaders might miss early warning signals, you notice when top performers start showing up late, when client communications shift tone, or when industry metrics begin trending downward. These observations enable proactive responses that prevent problems rather than manage crises.

3. Your Skepticism is an Intellectual Immune SystemEvolutionary psychologist Gad Saad’s research on “idea pathogens” explains why you often feel uncomfortable with popular strategies that everyone else embraces enthusiastically. Just as biological immune systems protect against physical viruses, psychological immune systems protect against harmful ideas that can destroy organizational effectiveness.

Your resistance to consensus thinking reflects evolved defenses against collective delusions that could prove catastrophic. When trendy management approaches make you uneasy, your intellectual immune system may be detecting hidden risks that groupthink overlooks.

Historical validation: Financial markets consistently collapse when skeptical voices finally gain attention. The anxious investors who worried about dot-com overvaluation, housing bubble dynamics, and cryptocurrency mania were expressing evolved defenses against collective irrationality.

Practical application: Your discomfort with popular strategies may reflect accurate assessment of risks that confident leaders ignore. Organizations benefit when anxious leaders voice concerns about widely accepted approaches that could prove expensive mistakes.

4. Your Gender-Specific Anxiety Pattern is Evolutionary SpecializationAnthropologist Helen Fisher’s research reveals that successful human societies employed complementary leadership approaches that correlate with modern gender differences in anxiety expression. Both patterns serve essential organizational functions.

Relationship-focused anxiety (often estrogen-influenced) enhances social sensitivity, increases collaborative problem-solving, and improves conflict prevention through early intervention. Leaders with this pattern excel at team development, culture building, and stakeholder relationship management.

Competition-focused anxiety (often testosterone-influenced) enhances competitive awareness, increases strategic planning focus, and improves organizational threat assessment. Leaders with this pattern excel at resource allocation, crisis response, and market positioning.

The key insight: Neither pattern is superior. Each evolved for different survival challenges and organizational needs. Understanding your specific approach enables strategic development that leverages natural strengths while building complementary capabilities.

Modern integration: The most effective organizations leverage both anxiety patterns either through individual leaders who can access multiple modes or through complementary leadership teams that combine relationship and competitive strengths.

5. Organizations Desperately Need Your Ancient SkillsCurrent business conditions create unprecedented demand for exactly the capabilities that anxious leaders naturally provide:

Complexity requires nuanced thinking. Modern problems resist simple solutions. Climate change disrupts supply chains unpredictably. Global teams require cultural sensitivity. Regulations shift rapidly across jurisdictions. Your tendency to consider multiple scenarios and prepare for different possibilities produces more robust strategies.

Remote work rewards emotional intelligence. Virtual leadership requires exceptional social sensitivity to maintain team cohesion across digital platforms. Your anxiety about team dynamics translates into superior remote leadership through proactive communication and relationship maintenance.

Stakeholder capitalism demands ethical sensitivity. Organizations must balance employee welfare, customer satisfaction, community impact, and shareholder returns. Your moral anxiety about fairness and long-term consequences enables decision-making that builds sustainable value.

Research validation: MIT studies show that remote teams led by high-empathy managers achieve 25% better performance than those managed by traditional task-focused leaders. Your social anxiety provides exactly what modern organizations require.

The Transformation ChallengeUnderstanding that your anxiety represents evolutionary intelligence rather than personal weakness provides the foundation for strategic leverage. Sadly, knowledge alone isn’t enough. The transformation requires developing practices that maximize the benefits of your ancestral wisdom while minimizing the physiological costs of modern organizational contexts.

This means learning to channel anxious energy toward productive planning rather than endless rumination. It involves creating organizational environments that provide the control, predictability, and social support your psychology requires for optimal performance. It requires building teams that complement your natural strengths while protecting against the overwhelm that destroys effectiveness.

Most importantly, it means rejecting leadership development approaches that treat your psychology as weakness requiring correction. Your anxiety feels terrible, but it’s your sophisticated intelligence requiring strategic application.

The Competitive Advantage Hidden in Plain SightWhile business culture continues promoting calm confidence as leadership ideal, organizations facing complex challenges increasingly need leaders who think systemically, prepare thoroughly, and respond empathetically. Your evolutionary inheritance provides exactly these capabilities.

Your worry activates intelligence systems that enhance threat detection and opportunity recognition. Your social sensitivity enables relationship management that drives team performance. Your systematic thinking produces comprehensive planning that prevents costly mistakes.

The revolution is already here. Organizations that recognize and leverage anxious leadership capabilities will outperform those stuck in outdated models emphasizing dominance and overconfidence.

Your anxiety isn’t actually holding you back from leadership success. It’s the secret weapon that makes that success possible.

[image error]