Aaron H. Arm's Blog

August 9, 2025

3 Ways to Make Your Prose More Engaging

April 23, 2025

I Have No Clout, and I Must Seethe

May 6, 2024

The Wrong Words at the Right Time

... because, wait -- is that not the right word??

I'm astounded by the lengths to which people will go to defend this one.

I'm astounded by the lengths to which people will go to defend this one.We've all had that friend, family member, or coworker who seems to mishear common words or phrases and then repeat them incorrectly. Maybe it's just their own little idiosyncrasy—I was once acquainted with someone who would say "Mice as well" in lieu of "Might as well." Usually, however, these not-quite-right phrases are part of a larger misunderstanding. As these misunderstood words catch on and gain a colloquial life of their own, they become almost valid in their own right. Almost.

But therein lies the problem: A misused word, phrase, or expression, even if widely used and commonly understood, may still be nonsensical when given a bit of scrutiny. Words do, after all, mean things. And until the words themselves completely change, both descriptively and prescriptively, it's best to use them "properly." After all, the very heart of language and communication is to work toward a shared understanding of ideas.

So, what do we call these tiny aberrations of language? Malapropisms!

You might have heard or read someone bemoan that it's a "doggy dog world" when, in fact, the expression is a dog eat dog world.

How about someone urging that you "nip [a problem] in the butt," when they mean to say nip it in the bud.

And then, of course, there's the person who prefaces their statement with, "For all intensive purposes," when it should be For all intents and purposes.

Has anyone told you to "be weary" of something? Unless they're instructing you to fall asleep, they're probably cautioning you to be wary.

I bet you've done this one: If you want to refer to "a whole 'nother" issue, you really mean a whole other issue. This comes from interjecting "whole" in the word "another," so it effectively becomes "a-whole-nother," which makes sense when we say it out loud. But it's slang in that sense, so be intentional with how you use it.

These are prime examples of the malapropisms making little to no sense—and the original wording making a whole lot more sense—when you stop to think about it. But that's the nefarious nature of these common sayings: We understand the connotation from context, and we therefore associate the words with that meaning, regardless of what the words themselves actually denote.

But these examples are also more likely to be corrected in time, either through self-realization or an all-too-eager grammarian in the audience. How about some issues that tend to fly under the radar?

Let's face it: We're all prone to repeating words that look and sound correct without much second-guessing. So, when the difference between two words is subtle, it can be hard to catch. In some cases, the improper version might even be more commonly repeated than the original. So, here's a list of some mistakes that I think are sneakier in their misuse, but are misused all the same.

Note: I'm hesitant (but not reticent) to conflate any misused word or wrong homonym as a malapropism. As exemplified above, I tend to think of malapropisms as involving expressions or colloquialisms. So, in the interest of pedantry, let's just call these "commonly confused words":

Reticent: If you're reticent, you're withholding your thoughts or feelings. You are reserved. It may involve emotional hesitation, but it is not a synonym for hesitant.

"Sally was new to the class and therefore reticent."

"Sally was hesitant to jump into the pool, as she did not know how to swim."

Compliment: This is a show of admiration or affection. If you want to express that one thing fits nicely with another, then they complement each other.

"Dave complimented my tie."

"Dave said that my brown tie complemented my brown shoes."

Hung: The past tense differs, here. When an object is suspended, it's hung. When a person is killed by hanging, they are hanged.

"He hung a picture on the wall."

"He was hanged for his crimes."

Disinterested: This means not having bias or a personally invested opinion. Think "dispassionate." If you are simply bored or apathetic, you're uninterested.

"A judge should be disinterested in the defendant's fate."

"Even though I was uninterested in algebra, I still did my homework."

Adverse: Harmful or unfavorable. Not to be confused with averse, which is when you oppose something.

"This drug may have some adverse side-effects."

"I'm averse to driving on that street due to the potholes."

Musk(y): This is my favorite mistake! "Musk" is what animals produce (like pheromones), or how we describe the pleasant smell of a person. If you're describing an old, moldy, dusty smell, try musty.

"Lisa missed the musky scent of her husband's cologne."

"Lisa ventured into the musty attic."

Incidence: This describes a rate or frequency of something repeatedly occurring, as in statistical analysis. If you want to refer to a single occurrence, it's an incident. More than one incident is "incidents," not "incidences."

"The poor working conditions resulted in multiple injurious incidents."

"There's been an increased incidence of anxiety among the population."

Lie vs. lay: Buckle up. This one gets tricky.

Lie is what you, yourself, do. You might lie on the floor or tell a lie."Jim said that he would lie down for a bit, but he lied."

Lay is what you do to something. You might lay bricks or lay a baby down in bed."Jim told me to lay the money on the table."

But wait, it gets worse. They past tense of "lie" is "lay" (unless you mean to tell a lie, in which case it's "lied"), and the past tense of "lay" is "laid." See here for a more complete reference of conjugating these verbs.

Apropos: There's nuance here. Traditionally, this means "relevant" or "in relation." So, we'd say that Topic 1 is apropos to Topic 2. In some contexts, people have used this to mean that something feels apropos when it's appropriately relevant. Over time, it's becoming increasingly used as a synonym for "appropriate," but a more discerning audience might judge you for that usage.

Traditional usage: "Apropos to our conversation on climate change, I'd like to talk about my new electric car."

Alternatively: "Oh, you bought an electric car after all this talk of climate change? How very apropos."

Not quite right: "Your behavior is not apropos for this place and time."

Bonus ~ Begs the question: This expression used to have a more specific and rhetorical meaning, which has since been lost in everyday use. If you'd like to avoid the silent judgment of pedants and linguists, consider this:

"Begging the question" is a logical fallacy in which the speaker assumes some premise that has not yet been established:Claiming that "Bigfoot is an anarcho-capitalist and therefore anarcho-capitalists are primitive" begs the question of Bigfoot's existence (among other things).

Commonly, people use this phrase to simply mean that one idea elicits a new question. However, there's admittedly a lot of crossover here. Oftentimes a question is raised precisely because something was erroneously assumed. But if you want to be especially intentional with your phrasing, see if the situation is apropos to the original definition.

It's ok. We can all be a little pedantic. That's part of the fun of learning these things. I'd love to hear which malapropisms or weird language quirks you've overheard.

~ Happy writing!

January 31, 2024

The Most Common Proofreading Corrections

... because why not learn from others' mistakes?

Some errors need to go the way of the typewriter. Et tu, dear writer?

Some errors need to go the way of the typewriter. Et tu, dear writer? In my time as a editor, I've come to two fundamental conclusions about people's writing:

Everyone needs a unique editing approach to address their writing challenges and elevate their own style. 100 writers will have 100 different voices, and there's no single prescription for how to improve any given piece of writing. There are a select few errors that most people make, regardless of their own style or proficiency.It's a funny thing, really: Even the most seasoned writer with a mature voice and expansive lexicon seems to fall into the same grammatical traps as every other writer, at least once in a while. These aren't matters of storytelling, but simple conventions that proofreading aims to correct. They're the sorts of errors you'd expect to see on an earlier draft, and which you'd expect an editor to fix, so I'm not surprised that I keep seeing them. But as long as I'm noticing them, I might as well pass that knowledge along to you. After all, if you can get it right the first time, it's one less problem later.

Note that these are relatively small things--matters of mechanics or conventions that are arguably beholden to a style guide somewhere. But they would get fixed in editing nonetheless, so at the end of the day, they still need correcting.

Without further fuss or fanfare, I give you my wholly unofficially and anecdotal "most common proofreading corrections."

The CorrectionsLet's just look at how these things should be implemented correctly, so you can compare them against your own practice. Please note that I use U.S. English conventions for the following examples.

Punctuating dialogue

For dialogue that's appended with a dialogue tag (e.g., "he said" or "she exclaimed"), use a comma to end the dialogue's statement: "Hippos are surprisingly dangerous," she said. For dialogue without a tag, including when followed by an action, use end punctuation: "Hippos are surprisingly dangerous." She pointed at the nearby hippo. For dialogue that's interrupted by narration: If the narration interrupts a single sentence of dialogue, use commas. Capitalize accordingly as one comprehensive sentence: "Hippos," she said, pointing at the nearby hippo, "are surprisingly dangerous." If the narration splits two sentences of dialogue, treat the second sentence of dialogue as a new sentence: Whenever possible, follow conventional punctuation rules within dialogue. Some writers opt to break punctuation rules for character voice, such as with comma splices . In most instances, this will simply convey awkward punctuation more than a specific voice/tone, and it will probably get fixed by an editor.Missing commas

When you join two independent clauses (i.e., complete statements) with a coordinating conjunction (e.g., "and," "but," "or"), use a comma with the conjunction: I like pie, and I like cake. I like pie, but I also like cake. When you use an introductory word, phrase, or clause in a sentence, follow with a comma: However, not everyone likes cake. Sitting alone, I ate my cake. When I was three, I ate my first piece of cake. Use commas to offset non-restrictive clauses within a sentence (i.e., additional information that doesn't change the sentence's essential meaning): My three children, who are all voracious eaters, prefer pie over cake.Em dashes

Ideally, an em dash (—) shouldn't be interchangeable with a period or ellipsis. Try to use it sparingly so as not to distract readers. Conventionally, it's used for the following purposes: Use an em dash to indicate an intentional break in a sentence's structure or grammar: Use em dashes to enclose clarifying statements: Use an em dash to indicate an abruptly interrupted thought, such as a someone being cut off in dialogue:"I'm not trying to argue with you, it's just that—" An em dash (—) is different from an en dash (–) and a hyphen (-). Make sure you're using the correct mark, and note that most style guides call for no spaces on either side of it.Ellipses

In academic writing, an ellipsis (. . .) indicates the omission of information. In narration or dialogue, an ellipsis indicates trailing off. Some writers use ellipses often to express characters' uncertainty or lingering thoughts. Try to use them sparingly so as not to litter your dialogue with it and potentially distract readers. Like an exclamation point, it should carry tonal weight, which is cheapened if overused. Don't begin dialogue with an ellipsis. Style guides have different formatting rules for ellipses. The Chicago Manual of Style, which is what many publishers use (and which formats well on e-books), calls for 3 periods with spaces between each character: . . .If that seems like a lot of rules, I beg to differ! This is but the tip of the proofreading iceberg. And yet, it encompasses a disproportionately large number of edits across writers of all ages and persuasions, so I implore you to keep them in mind.

Happy writing!

April 2, 2023

The Right Way to Ask for Feedback

...because asking "Is this good?" isn't good.

If you want good answers, you need to ask good questions.

If you want good answers, you need to ask good questions.During my time as a teacher, I witnessed an interesting pattern among students who were able and willing to ask questions.

Like many teachers, when I sensed even the slightest hint of confusion in my students, I made a habit of asking, "What questions do you have?" Now, it probably doesn't come as a surprise that most students didn't ask questions, even when prompted--ever. However, I don't believe this was due to shyness, boredom, disengagement, or anything of that sort. Rather, I believe that most students legitimately didn't have any questions... or, to be more precise, they couldn't think of any questions to ask. When students did ask clarifying questions with any regularity, those questions were pertinent and absolutely helpful for their understanding. But that's not all these students shared. When it came to which students were most likely to ask relevant questions, I noticed a trend: they were proficient in the content without having yet mastered it. In other words, they mostly knew what they were doing, but struggled slightly with an occasional concept.

In pedagogy, this is called the zone of proximal development (ZPD). It's a place where the content is accessible to a learner, but it's still challenging enough that they'll struggle a bit to internalize new concepts. They might be able to get there on their own, but with a little guidance they can thrive. This is where everyone should ideally be on a journey of improvement: remaining challenged while still having attainable goals.

But what about the majority of students who weren't in that ZPD? The students for whom the content was too easy, who intrinsically understood all relevant concepts, didn't have any questions to ask. They legitimately didn't need to ask anything, because there was nothing new for them to learn at that juncture. Meanwhile, for those who were struggling significantly, they didn't understand enough of the content to even know what questions to ask. It's a sad irony that those who need the most help to learn are unable to utilize the most essential tool for learning: targeted questioning.

It's a sad irony that those who need the most help to learn are unable to utilize the most essential tool for learning: targeted questioning.

When it comes to writing, feedback is like a student-teacher relationship**. If you want to improve, you should seek out remediation from someone whom you trust to guide you in the right direction. However, writing is no simple task. It's not only a matter of grammar, structure, clarity, punctuation, organization, idea development, or any singular facet; it's a complex marriage among all of those, which writers must implement simultaneously. This is why no one is simply taught to write, but rather we are taught each of those skills at different points over time. It would be overwhelming to focus on every potential facet of writing in a single lesson, for teachers and learners alike. Questions about writing are therefore no different. They need to be specific to a skill, and you need to understand what skill you're looking to improve. And since asking for feedback is just another form of questioning, you need to know what type of feedback you want.

With this in mind, allow me to share the bane of every feedback provider:

Is this good? Do you like it? Just any general feedback, please. What should I change? Is it okay?If this is what you're asking, then you might as well not ask anything at all. This might sound harsh, but it's true: these requests are meaningless because they have no focus, and if you're not asking for focused feedback, then you're asking your reader to consider (and evaluate) every potential aspect of your writing. That's overwhelming. Worse yet, you're essentially rolling the dice on your feedback, because your reader might prioritize anything. You won't know until you receive the feedback, at which point it's too late to ask the reader to reconsider how they're reading (at least, if you want to be polite).

...if you're not asking for focused feedback, then you're asking your reader to consider (and evaluate) every potential aspect of your writing. That's overwhelming.

So, how do you ask for focused feedback? It's simple: think of yourself as that student who mostly understands the content, but might not be totally confident in a certain aspect of it. Hopefully, you do understand most of your own writing. But maybe something feels a little unpolished. Maybe you're worried about the pacing, characterization, dialogue, or something simple like overusing em dashes. This is what feedback is for. Ask your readers to pay attention to those specific points that you're worried about.

If you don't know what to ask--either because nothing feels problematic or everything does--then you're probably not ready for feedback. You need to understand your own writing well enough to know how it can potentially be improved. To bring this back to the ZPD, consider how confident you are with your work:

If you're overwhelmed with potential improvements to the point where you want your reader to focus on everything (or, worse yet, you're hoping they'll fix it for you), then you might be struggling with too much to see one clear path for improvement. Either revise that draft or shift to a different project that's more manageable. Or, if you really want to capitalize on a learning opportunity, pick one or two facets of writing for your reader to respond to, regardless of anything else they see. This at least gives you a skill to identify and work on, going forward. If you think you have a polished story without any room for improvement... well, what are you seeking feedback for? Seriously, if you just want compliments, then you might as well start looking to publish. On the other hand, if you're both confident in your work and humbly looking to improve it further, then think big. Ask readers to evaluate your pacing, plot arc , character dynamics, etc. Even if you love what you have, choose something for others to critically evaluate. If you're mostly happy with your story, but can see certain aspects of it that might not be totally effective, then you're in the ZPD. You're ready to ask those focused questions and learn from the focused feedback you receive.Of course, all of this hinges upon the feedback being valuable. That means having a reader whose judgment you trust and who understands the craft well enough themselves to offer feedback that's insightful, relevant, and actionable. But that's a topic for another day.

Happy writing!

**The goal of a feedback provider is, of course, to help you improve. In this way, we can think of them as having a similar role to a teacher or mentor. However, the power dynamics between a writer and a critical reader shouldn't be so firmly ingrained. Feedback is always a suggestion to be accepted or rejected, and neither party's ego should be tied to this fact. Maintain a ,growth mindset and embrace criticism, but also acknowledge that no feedback--not even from a seasoned writer--is sacrosanct.

September 22, 2022

The Overreliance on Plot

...as opposed to, y'know, the writing.

Is your plot the best aspect of your story? Should it be?

Is your plot the best aspect of your story? Should it be? Let's get this out of the way: all stories need plot. And having a good plot is, well, good. Do you have a good plot? That's good.

There. Now we can move on to a bit of nuance. Namely, I'd like to posit that the plot isn't the most important part of a good story. It's probably not the first thing that will engage (or disengage) readers, it's not what elevates a story to being a Classic™, and it's not where aspiring writers should be putting all their energy.

Plot isn't everythingBy definition, your plot is what happens in your story. At first, that may seem like it's the first and foremost aspect of storytelling. It is the story. But this is the trap that many writers fall into: the assumption that having interesting things happen is what makes a story interesting. In fact, that's the easy part. Anyone could conjure an interesting sequence of events.

Case in point: imagine a young child telling you a wild story. Maybe a dragon fights a giant robot; maybe a werewolf falls in love with a clone of Elvis; maybe aliens visit the planet and force raccoons to evolve into the superior species, giving them dominion over the planet. These things are, in and of themselves, interesting. But if they're told as a rambling, run-on chain of events that sounds like an incomprehensible fever dream--as young children are so apt to do--it's just not going to feel like a cohesive, well crafted, engaging story. At a certain point, you're likely to tune the kid out. Why? Because no matter how interesting the plot is, storytelling is all about execution.

So how does one "overrely" on plot?My fear isn't that writers spend too much time or attention to their plot, but rather that they'll rely on their plot alone to carry the work. Personally, I spend a great deal of turmoil over wanting to have an interesting premise/plot and then a great deal of time outlining it. But even then, I recognize that the events themselves aren't inherently interesting to anyone else until I make them interesting. To that end, I believe that writers should see their style and voice as the ultimate selling point of their work.

I believe that writers should see their style and voice as the ultimate selling point of their work.

Moby Dick didn't get adopted into the literary canon because people were clamoring to read about a man on a boat (see also: The Old Man and the Sea). Even 1984, with a far more interesting premise, is just one dystopian novel among thousands. What set them apart, and what continues to set apart successful works, is literary voice. When a reader picks up a book and evaluates the first couple of pages, they don't care about the plot--it hasn't developed yet. They don't even care about the characters, who similarly haven't been developed. What readers will care about is whether the story feels engaging, and that all comes down to your voice.

So, here's how I see an overreliance on plot as a potential pitfall: developing writers will write for the plot. They'll write just to get to the next scene, or they'll assume that the events--simply by virtue of transpiring--are interesting. With that assumption may come a lack of detail, inconsistent pacing, an imbalance of dialogue vs. narration, or simply an all-too-straightforward tone that does little to engage readers.

The advice I'd give, here, is not dissimilar to the advice I'd give a young child recounting their rambling fever dream: start with the assumption that your plot isn't interesting by itself. I'm sorry, but that's the harsh reality of storytelling. Every story has already been told anyway, so realize the challenge is in the artistry of your voice. Realize that you need to make the story interesting in how you tell it.

Start with the assumption that your plot isn't inherently interesting [...] Realize that you need to make the story interesting in how you tell it.Find your voice

I realize that the crux of my advice obnoxiously boils down to, "Just write better!" When put thusly, it doesn't sound helpful at all. But the writers whom I've seen improve the most are the writers who understand what to focus on. And--of all facets of writing--plot is not something with which writers generally need help. If you're feeling creative, then you can probably concoct an interesting (even complex) series of events. So, if you're just focusing on how cool your plot is while you write, you might very well be neglecting the writing itself.

To pull yourself out of this habit, consider the following activities:

Try writing about a subject that you don't think is inherently interesting, but focus on the quality of your writing. Utilize an engaging voice. Pull the reader into a rant, musing, reminiscence, or imagining about something that is only interesting because of how you tell it. Try writing a genre that you don't normally write. You may not be invested in it at first, but use your unique writing voice to make it your own. (This is much like how readers aren't initially invested in any story until that story pulls them in. So, do that for yourself; make yourself enjoy the genre by writing it well.) Find a story from another writer that you don't like. Analyze why you don't like it. What is it about the writing that doesn't engage you? Now, apply that same level of criticism to your own writing. Start looking at how you can improve the writing itself, regardless of the plot behind it. Finally, read a book from one of your favorite authors, and pay attention to how they write. Ignore the story itself, if you want. Absorb the word choice, sentence structure, mood, pacing... just revel in the way that author tells the story. Emulate them if you want, or just adopt some of their tricks in your own way. The important thing is that you value the art of storytelling beyond the story it tells.Happy writing!

June 28, 2022

The (In)authenticity of Dialogue

...and why characters need to have imperfect speech.

Pro-tip: Don't let the reader remember that you're controlling your characters.

Have you ever replayed a conversation in your head? You might have been in the car or in the shower, going over what you could have said to that person. With each iteration of the imagined conversation, you conjure a better response until you hit upon the one--what you wish you could have said or done in the moment. And maybe, if you're really lucky and just the right amount of clever, you'll land a couple of those witty retorts in the real world. But how often do they happen, really? How often do we manage to say the perfect words at the perfect time in real life?

There's a reason these moments are usually limited to our daydreams. Even the most articulate and confident speakers are imperfect in their speech. Conversations happen in real time, and as a result, we're essentially "winging it" when we talk. Every sentence is a dozen split-second decisions about diction, syntax, and tone (at the very least). We simply cannot choose the coolest, most polished version of our words every time we open our mouths. So why would we write our characters like that?

We simply cannot choose the coolest, most polished version of our words every time we open our mouths. So why would we write our characters like that?

Good dialogue, like any bit of characterization, is a matter of authenticity. And if the most authentic way to portray a person is through their flaws (which I believe it is), dialogue should be no exception.

When everything is cool, nothing isThe classic adage of "everything in moderation" applies here. Characters are allowed to say cool things, of course. But if everything out of their mouth is a clever, snappy comeback? If they always have the right interjection for the right occasion? That character trait will be self-defeating because it will only turn them into a cliché, and nothing is less cool than a cliché.

This problem becomes even worse when we get a constant back-and-forth stream of witty repartee. It's like using an exclamation mark at the end of every sentence. Once is enough! Twice is overkill! Three times is silly! Four times verges on parody! If every statement has an impact, then it becomes a barrage of monotony! Yes, excitement can be monotonous! So, too, can a barrage of clever quotes be monotonous!

How do people talk?This is a serious question and an important one at that. If you want your characters to feel real, they have to sound real. So, what do real people sound like? Let's examine:

Real people DON'T:

Impart wisdom with every word Constantly have the perfect joke or remark ready Use perfect grammar and flowery language in casual conversation Always say exactly what's on their mind Always understand each other Always anticipate what others will sayIn sum, real people don't get much time to think through their responses first. Conversations happen in real time. So even if you're putting a lot of forethought into what your characters will say, it shouldn't sound that way.

Real people DO:

Stutter, misuse words, say things awkwardly Pause to think Use improper grammar and casual language Misunderstand each other Cut each other off Sometimes give one-word answers or non-answers Ask clarifying questions Sometimes have to correct themselves Use conversational fillers ("um," "uh," "like") Have their own speaking styleThis is not to say all of your characters (or any of them, really) should be an incoherent mess of awkwardness. But consider what real conversation sounds like among you and your friends/family/colleagues/strangers. People don't converse because they already understand each other; they converse in the pursuit of understanding each other.

People don't converse because they already understand each other; they converse in the pursuit of understanding each other.

And, as is the case with any pursuit, there are obstacles to overcome. Inject some conversational obstacles into your dialogue, so the conversation itself can be an authentic exchange of two imperfect individuals.

A case study in authenticityLet's look at two examples of dialogue. In both examples, the same scene is playing out between Chris and Mary. Note that the narration is kept minimal so we can focus on the dialogue:

Example A:

"So, what do you say? Shall we head there together?" Chris asked. "Together?" Mary responded. "That implies equality, and I don't believe you've proven yourself my equal. No, we shall not go 'together.'" "My, my! Aren't you full of yourself? It was a simple question, and I meant nothing by it. Would it help if we framed it as me accompanying you? Your escort or entourage, if you will?" "Perhaps, but then I wouldn't get the satisfaction of watching you weasel your way out of your words," she said with a smirk. "If only I were a weasel, then perhaps I'd elicit a bit of sympathy from you." "Sympathy, yes. Empathy, no. And I'd wager the latter is precisely what you're seeking." "What I'm seeking," he insisted, "is your company for the evening. Nothing more, nothing less. Therefore, if your answer is no, our business here is over." "Over your head, and out of your league," Mary said.

Example B:

"So, do you want to go there?" Chris paused, then added, "together?" "Together?" Mary responded. "What, like, the two of us? 'Together' together?" "Yes?" "Ok, but don't you think you're a little--well, just that I'm--" "What? "You know," she said. "I'm out of your league." "Wow, ok. Well, would it be better if I just joined you, then? It doesn't have to be a whole thing." "Mm, maybe." Mary's words hung in the air for a moment. "But I gotta say, I like this side of you." "What do you mean?" "Just the way you're being humble about it." "Well, at least I get some sympathy points," he muttered. "Yeah, sympathy points. But that's it. I don't think we're really on the same level yet, you know?" "Whatever," he said with a sigh. "I was just asking if you wanted to go out. If you don't want to, that's fine." "Yeah, I don't think so," Mary said.

Granted, the first example is probably more entertaining. It certainly takes a loftier approach with language. But as we noted, you can only sustain that for so long before it gets tedious. Example B is far more down-to-Earth. We can imagine those characters as real people: they're trying to understand each other and be understood, with some bumps along the way and language that ebbs and flows in its effectiveness. Moreover, we're left to imagine the thoughts and intentions behind those words.

Dialogue is what we or our characters choose to say in a given moment. Therefore, it's refracted by our tendencies, our choices, our moods, our imperfections. Let dialogue feel alive by giving it pacing. Let it breathe, let it stumble, let the conversation find its way. Don't force your characters into clichés by making them say the sort of things you wish you could; let them be just as real as you are.

Happy writing!

April 7, 2022

The Trap of Overplanning Your Story

...yes, you can be too prepared.

How long are you going to stare at your notes until they materialize into a story?

How long are you going to stare at your notes until they materialize into a story?In writing circles, there's a cutesy term for the (arguably oversimplified) dichotomy of writing types: planners vs. pantsers. A planner is exactly what it sounds like: one who plans their story to any significant extent before they begin writing. A pantser is one who simply writes and allows the plot to unfold through that writing--as in, writing by the seat of one's pants. Now, you could find a plethora of other blog posts or articles on this topic if you're so inclined to find out where you fit in. Personally, I don't put much stock in people's own writing processes. But I do see many writers, particularly younger writers, fall into a certain trap when they invest all their energy into the planning phase, and so I'd like to address the concept of overplanning. (Pantsers, you're off the hook for today. Go enjoy your life with the disorganized, reckless abandon you are so fond of.)

First, let me perfectly clear: planning is good. It can be great. I've used pages-long outlines to plot out a story, its foreshadowing, motifs, and details about the world, lest I forget or fail to connect my own dots. Planning and outlining can be nothing short of invaluable.

The TrapBut herein lies the trap: when planning becomes the creative outlet through which someone invests their pride and energy, it tends to grow... and grow... and eventually, the planning phase itself becomes the story. And that's dangerous. Why? Well, if the outline feels increasingly like a fleshed out story or world, then properly writing it out may increasingly feel like a chore. After all, you've already completed the fun part of storytelling: creation. When there's little left to create or discover or experiment with, then writing becomes more a formality than an art form, and who wants to do that?

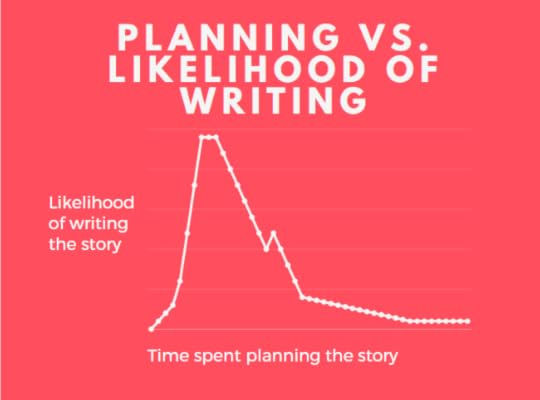

Here's a graphical representation of the trap of overplanning, as I see it:

Assuming you need some outlining and notes to get your story off the ground, then the initial planning phase is constructive. But at a certain point--once you theoretically have enough to get started--the planning phase will plateau in efficacy. And past that point, when your planning becomes extra information for fun, you risk falling into a canyon of story stagnation. (I put a little glimmer of hope in there on the way down, because I choose to believe there's a point at which some writers recognize this trap and summon the motivation to start writing; I am no cynic.)

Fantasy Writers, BewareI won't mince words: I see this problem far more among young fantasy writers than I do among other genres or demographics (although historical fiction comes close). I imagine this is because fantasy worlds inherently require world-building, and it's why a lot of fantasy writers enjoy the genre in the first place. Of course, this raises the question of how much world-building is really needed to start writing the story, and it's all too easy to overestimate the answer.

Let's say you're writing a high fantasy story in which there are multiple kingdoms across multiple continents, replete with mythical beasts, magic, and millennia of history. Clearly you need some idea of these things in order to plot out a story that intertwines them. You might need to know how many continents there are, their general placement in the world, and the general topography therein. You might need to know the cultures of the predominant kingdoms and their relation to each other. You might need a rough understanding of how magic works in this world and how people have used it historically...

Keep in mind that all of these things, as potentially expansive as they are, could be answered succinctly. These could be bullet points, perhaps sub-bullet points and sub-sub-bullet points, but succinct notes nonetheless. However, once you've written a page on the history, lineage, and cuisine of one of your kingdoms, you've already entered overplanning territory. Your reasoning may be sound: You want to place your characters in a fleshed out world. You want immersion. But ask yourself this: Would these details not come out in the writing? Could you not figure them out as the story unfolds? And more importantly, is it not possible that these details might be even better if you decided them within the context of your writing?

Is it not possible that these details might be even better if you decided them within the context of your writing?

Hey, I get it: world-building is fun. Though if you have all your fun building a world, then you may get bored with it before you can turn it into a story. And I suppose that's alright if your goal is just to have fun and be creative. But it's not a story until.. well... you've stared writing a story.

So, What Now?If you're in the planning phase, just keep a couple of questions in the back of your mind:

Could I confidently explain my main characters, setting, and conflict in a few sentences? Could I write the first chapter?If you can do these things, you could start writing. Additionally, consider asking yourself this dangerous question:

Am I eager to start this story?If you're really planning for a story, you should be excited to start writing it. Once you begin feeling hesitation toward the writing stage, perhaps because you've transferred all your excitement to the planning or because the planning seems unending, I'm sorry to say you've overplanned.

Luckily, the cure is simple: put the notes and outline aside. Don't even look at them. At this point, you certainly know enough of your world by heart to begin writing. So, sit down and write.

Happy writing!

March 25, 2022

The Myth of Writer's Block

...and what to do about it.

Typewriters are antiquated, and so is the bugbear of "writer's block."

Typewriters are antiquated, and so is the bugbear of "writer's block."Picture this: you're sitting in front of your word processor (or notebook, for you tactile types), staring at a blank page that has also been staring back at you for longer than you care to admit. Maybe you're toiling over the perfect opening line, maybe you're trying to work out the premise, or maybe you have no specific goal in mind and therein lies the problem. Whatever is inhibiting you from putting words on the page, the beast known as writer's block lurks in the recesses of every writer's mind, occasionally--or, perhaps, all too often--coming out to terrorize their progress. But here's the thing: it doesn't have to. In fact, I'd argue that the way we view "writer's block" as an inhibiting force is self-defeating and self-perpetuated... to the point where I might even call it a myth.

To vanquish writer's block once and for all, let's first examine the various ways it can manifest. Depending on where one is in the writing process, the solution might look different. So, let's begin with the problem of a blank story premise because, as a friend once told me years ago, starting places are a good place to start:

Exhibit A: You want to write a story, but you can't settle on a story premise.

Good news! This doesn't have to be writer's block.

"I'm sorry, what?" you say in a small fit of indignation. "Of course this is writer's block. I don't know what to write."

And that's true, traditionally speaking. But I'd like to suggest a new paradigm for how we frame writer's block: it is the struggle to produce writing. If you're struggling to produce an idea, it may help to realize that you could still write if you wanted to.

This is where you roll your eyes so hard they slow the Earth's rotation, adding, "I can't write if I don't have an idea."

Counterpoint: You can't write the hypothetical idea you don't have, but you can write. If your goal is to write a story, you can always write something. Maybe that sounds like an unhelpful truism, but hear me out. Too many writers wait around indefinitely, hoping The Story™ will dawn on them. Sometimes it does. But more often than not, our best stories are found through the act of writing. It's okay to write a story you don't love. It's okay to write something, anything, just to keep the creative juices flowing. Is it possible that after months of stagnant deliberation, your magnum opus will materialize in front of you? Sure. It is plausible? Not so much.

"It's okay to write something, anything, just to keep the creative juices flowing."

Of course, it's fine to put your writing on hold while you work out a story premise. However, if that "hold" has devolved into a prolonged case of writer's block that is starting to grow moss, maybe it's time to try that story idea you had previously crumpled up. It's better than nothing, possibly better than you thought, and very likely a creative road to your next idea.

Exhibit B: You can't find the motivation or inspiration to write.

Good news! You don't need to "find" motivation. It's almost certainly lurking within you, waiting to be unleashed. The trick is to realize that it's lying dormant, and all you need to do is sit down and write.

Analogy time: let's look at creative motivation as a matter of momentum. In this way, it's similar to driving a car. It's a matter of being stationary at first, but then gradually moving toward your destination. That's momentum. But there's a crucial step in both of these scenarios that writers overlook while drivers take for granted: you have to start the engine. When it comes to driving a car, it would be ridiculous to assume that we could get anywhere without starting the car. We know we need to sit in that car, start the engine, and accelerate from zero. No one simply wills their car to move from zero to sixty instantaneously, and we certainly don't do it without getting in the car first. So why do writers assume that they will magically find motivation (momentum) to write without sitting down and getting started?

"No one simply wills their car to move from zero to sixty instantaneously, and we certainly don't do it without getting in the car first. So why do writers assume that they will magically find motivation (momentum) to write without sitting down and getting started?"

In writing, starting the engine means sitting down and being physically prepared to put words on a page. It means going through the act of writing, even if it's a snail's pace, so that we can build momentum. We cannot and should not wait for the mood to strike us, no more than a driver should wait for their car to rev its own engine.

If you're waiting to feel inspired, you might be waiting forever. Consider that your inspiration is actually waiting for you to sit down and give it a medium.

Still not convinced? I kindly refer you to Newton's First Law of Motion.

Exhibit C: You're in the middle of a story. You want to continue. You have the

motivation to write. You just can't figure out what should come next...

Okay, so this might be a legitimate case of writer's block. If you're well into your story and have the momentum to continue, but simply cannot find the next logical scene, then you have my sympathy.

The silver lining here is that you probably won't be stuck for long, assuming you're making a good faith effort to map out the plot. Fortunately, this is a topic I plan to tackle in a future blog post.

But if you are mercilessly stuck, having driven your story into a dead-end from which you see no way of return, then I imagine you are left with 2 options.

1) Backtrack. Find where your story starts to go down a one-way street, and revise it. Take it in a new direction to open up more possibilities for yourself. It's okay to delete whole chapters if you need to. Don't let your story canonize itself; it is still a work in progress.

2) Put it aside and focus on something else. If your new endeavor leads to inspiration for your dead-end plot, then great! If not, you will still have a new piece to pour your ambition into.

That's it. That's how to get over writer's block. And since I don't want to approach the other end of the spectrum (prattling on needlessly), I'll end here, as I have nothing more to say.

Happy writing!

A brief addendum and disclaimer: I realize that the crux of my advice here--to get over writer's block by simply willing oneself to write--may be seen as an unhelpful over-simplification. The writing process looks different for everyone, and I'm not so naive as to think saying "just write" is a cure-all. However, I do believe that we often allow our creative stagnation to fester, and taking ownership of our writing habits is possibly the best thing we can do to combat that.