Collins Hemingway's Blog

December 12, 2020

More Austen on New ‘Channel’

Friends,

Let me provide an end-of-year thanks to all my subscribers. I hope during these very difficult times my thoughts on Jane Austen, the Regency era, and other related issues may have offered a small but welcome diversion from the pandemic and hard times and isolation that a lot of people are experiencing.

Many of you have been with me since I began this blog five years ago. A few are new. I hope all of you will join me as I continue to blog but from another location. I am “switching channels,” if you will, but the show will go on. The new website, https://www.collinshemingway.com, is replacing this one, austenmarriage.com. Nothing will broadly change. The new site is fully stocked with the sixty-plus Austen blogs I’ve written in the past, and I’ll continue as before. I may occasionally branch out a little further, but I intend to keep “Dear Jane” as the primary focus.

The main reason for the change is that I have also written five non-Austen books on a variety of topics, from high tech to the brain to corporate values. I have other books and projects, both Austen and otherwise, in the works. I need an online bookshelf to include everything that I’ve done and hope to do.

It was fun for me to go through and re-read the blogs as I cleaned up formatting issues related to the bulk transfer. In five years, I’ve treated Austen in many different ways: her life and possible loves; her writings; the issues that she and other women faced; movies about her works; even the way she spoke—it wasn’t in the posh “BBC speak” of today. Feel free to browse the blog section of https://www.collinshemingway.com.

My Thanksgiving blog has already gone out from the new site. I had to ensure the new email system worked before I shut down the old. Because the blog came from a new sender, it might have ended up in your spam or junk folder. Please check and follow the steps of your email provider to ensure that the system knows collinshemingway@hotmail.com is a legitimate address. It’s a good idea to check your junk folder regularly, anyway, for the occasional valid email that’s been misrouted. Adding collinshemingway@hotmail.com to your email contact list should also help ensure the mail gets through.

The next blog will issue on Christmas Eve and, not surprisingly, will contain a few Austen Christmas cheers.

Thanks again for reading my thoughts through the years. And stay safe. Let’s not get twitchy and expose ourselves to the plague now that we can see help on the way. A little more patience. …

And raise a toast to Jane on December 16 to celebrate her 245th birthday!

—

“The Marriage of Miss Jane Austen,” a trilogy that traces love from a charming courtship through the richness and complexity of marriage and concludes with a test of the heroine’s courage and moral convictions, is available from Jane Austen Books and Amazon. A “boxed set” that combines all three in an e-book format is available here.

The image of Jane Austen is from the Richards wax figure at the Jane Austen Centre in Bath.

The post More Austen on New ‘Channel’ appeared first on Austen Marriage.

November 25, 2020

Giving Thanks with Austen

This blog originally appeared last year. With my blog now scheduled on the fourth Thursday of each month—Thanksgiving in the U.S.—I decided to reprise it.

Thanksgiving makes me wonder whether there was any formal giving of thanks in Jane Austen’s work. The November U.S. holiday has spread to most of the Americas. The English have a more general harvest-related tradition of providing bread and other food to the poor, often through the church. That tradition was extant in the Regency and continues now.

Though today’s American celebration is secular in nature, the practice has spiritual roots. It was religious settlers in Virginia and Massachusetts who began the celebration. Most Americans know the tradition of the Pilgrims inviting the native tribes to join in. It was the Indians who provided the food that enabled most of the early colonies to survive the first desperate years.

President George Washington created the first official Thanksgiving in 1789 “as a day of public thanksgiving and prayer, to be observed by acknowledging with grateful hearts the many and signal favours of Almighty God.” President Abraham Lincoln memorialized the date as the fourth Thursday in November, beginning in 1863, when, in the middle of the Civil War, he proclaimed a national day of “Thanksgiving and Praise to our beneficent Father who dwelleth in the Heavens.”

Austen’s family was religious, of course. Her father and two brothers were clergymen. Her works contain strong, though not didactic, moral strains. I wondered: Did any of her characters ever directly express thanks—to God, to Providence, to the universe? Did anyone express gratitude in a way that recognized any higher power?

I could not find any direct use of “giving” or “offering” thanks in any of Austen’s six novels. Most of her novels contain fifty or sixty ordinary thanks each. Persuasion is the least thankful with only eighteen, but it includes the most fervent. Most of the thanks are a polite reflex to ordinary behavior or a specific response to a good deed performed by another.

“Thank God!” occurs once or twice per book. The sense is usually general. Sometimes the phrase is a positive and sometimes a negative. In Persuasion, Mrs. Croft thanks God that as a naval wife she is blessed with excellent health and was seldom seasick on the ocean. Perversely, William Elliot writes “Thank God!” that he can stop using the name “Walter”—the name of Anne’s father—as a middle name. Anne Elliot stiffens upon learning the insult to her family.

“Thank God!” is a remark that is canceled out in Northanger Abbey. Catherine Morland’s brother James writes her to say “Thank God!” that he is done with Isabella Thorpe, who is now pursuing Captain Tilney. The next post brings a letter from Isabella, telling Catherine “Thank God” that she’s leaving the “vile” city of Bath. By now dumped by the Captain, she doesn’t know that Catherine knows what’s up. Isabella pleads “some misunderstanding” with James and asks Catherine to help: “Your kind offices will set all right: he is the only man I ever did or could love, and I trust you will convince him of it.” Catherine doesn’t.

The only real “Thank God!”, as an appeal to the Deity, comes in Persuasion after Captain Wentworth’s inattention contributes to Louisa’s fall and concussion: “The tone, the look, with which ‘Thank God!’ was uttered by Captain Wentworth, Anne was sure could never be forgotten by her; nor the sight of him afterwards, as he sat near a table, leaning over it with folded arms and face concealed, as if overpowered by the various feelings of his soul, and trying by prayer and reflection to calm them.”

Everyone’s prayers are answered. Louisa mends and becomes engaged to Captain Benwick. Wentworth is free to marry Anne.

A deeply thankful attitude does exist with two of Austen’s characters. Readers who pause to think can probably guess the two. Beyond the village poor in the background, which characters are most in distress and most likely to be thankful for any relief?

We might think first of Mrs. Smith from Persuasion, who had the “two strong claims” on Anne “of past kindness and present suffering.” Her physical and financial straits are dire, yet “neither sickness nor sorrow seemed to have closed her heart or ruined her spirits.” Mrs. Smith, however, is more shrewd than thankful, using Anne’s marriage to help end her own suffering.

What character, living on the margins, has a level of energy that often sets into motion her active tongue? We find her in Emma:

“Full of thanks, and full of news, Miss Bates knew not which to give quickest.”

When Mr. Knightley sends her a sack of apples and the Woodhouse family sends her a full hindquarter of tender Hartfield pork, Miss Bates responds with the sunniest appreciation: “Oh! my dear sir, as my mother says, our friends are only too good to us. If ever there were people who, without having great wealth themselves, had every thing they could wish for, I am sure it is us.” She might be auditioning for a role in Dickens’ A Christmas Carol.

In contrast, the social-climbing new vicar’s wife, Mrs. Elton, feels thankful in a prerogative way. “I always say a woman cannot have too many resources—and I feel very thankful that I have so many myself as to be quite independent of society.”

If anyone has the right to feel a lack of thanks in life, it is Fanny Price of Mansfield Park. When she is not being forgotten, it is to provide some service for someone else. When she is not being ignored, it is to be abused by her aunt, Mrs. Norris. Just about every word that can convey melancholy, sadness, or anguish serves to repeatedly describe her.

She feels misery at least eight times; some variety of pain at least ten times; wretchedness half a dozen times. The best she normally manages is to feel both pain and pleasure, four times. She is oppressed three times and suffers stupefaction once. Her circumstances and personality leave her in a “creep mouse” state of mind. She trembles a dozen times; she cries a dozen times and sobs at least four other. The stress is so great that she comes close to fainting at least three times and is ready to sink once; she suffers fright or is frightened six times; she reacts with horror or to something horrible five times.

Yet for all her misery, and though she lacks a sunny disposition, she manages to look on the sunny side of life.

Fanny feels gratitude at least fifteen times, for things small and large. Gratitude for her cousin Edmund tending to her when she first comes to live with her wealthy relatives. For his providing her a horse to ride. For her uncle once letting her use the carriage to go to dinner. Even gratitude once “to be spared from aunt Norris’s interminable reproaches.”

Kindness comes up about 125 times in the book. The most common use again relates to Edmund: his kindness to her throughout, and his encouragement of others to be kind to her. Fanny can even feel grateful toward Henry Crawford, despite his character flaws, for his kindness to her brother and, a couple of times, for his kindness to her.

It seems to be a fundamental aspect of human nature that those with the least to appreciate in life treasure what they have the most. Austen’s treatment of Miss Bates and Fanny does not, I think, reflect a conscious attempt at moral teaching. Their attitudes flow directly from the women’s character. Fanny and Miss Bates are gentle souls with big hearts. They give thanks naturally for the joy of existence.

So should we all.

—

The Marriage of Miss Jane Austen, which traces love from a charming courtship through the richness and complexity of marriage and concludes with a test of the heroine’s courage and moral convictions, is now complete and available from Amazon and Jane Austen Books.

The post Giving Thanks with Austen appeared first on Austen Marriage.

October 30, 2020

Austen’s Words Soothe Soldiers, Home Folks

This year of 2020 is the seventy-fifth anniversary of the end of World War II. It is fitting, thus, to remember that Britain’s bulldog leader once benefitted from the soothing words of Jane Austen during the world’s largest military conflagration.

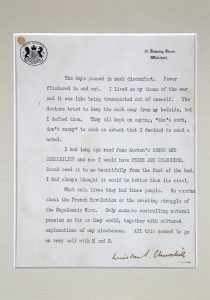

Churchill wrote of the comfort he got from listening to his daughter read him Pride and Prejudice during WWII. (Letter at Jane Austen’s House, Chawton.)

Churchill wrote of the comfort he got from listening to his daughter read him Pride and Prejudice during WWII. (Letter at Jane Austen’s House, Chawton.)Winston Churchill lay abed with the flu during the middle of the war. His doctors told him: “Don’t work, don’t worry.” In a letter now at Jane Austen’s House in Chawton, Churchill wrote that he had long ago read Austen’s Sense and Sensibility and decided to try Pride and Prejudice. He had always thought it would be “better than its rival.” His daughter Sarah read it to him, which she did “beautifully from the foot of the bed.”

Speaking of Pride and Prejudice, and no doubt contemplating the burdens of his own position leading the war effort, Churchill remarked in his letter: “What calm lives they had those people. No worries about the French Revolution or the crashing struggle of the Napoleonic Wars. Only manners controlling natural passion so far as they could, together with cultured explanations of any mischances.”

The prime minister’s observations, of course, were true of the characters in the novel, but not the readers. British military strength totaled about 350,000 during the Napoleonic Wars, and at least as many more were volunteers to be called in case of invasion. Citizens read of the battles, they kept abreast of the casualties, and they observed the thousands of wounded veterans begging for bread in the streets. They knew war as well as their descendants in later titanic battles across the Channel.

Churchill was by no means the only warrior to find solace from the words of Austen during the world wars. A Rudyard Kipling story describes a soldier who served in an artillery battery in World War I. Imagining the existence of a secret society of “Janeites” because the officers keep talking of her, he comes to read her novels. After being wounded in a barrage that wiped out the rest of his unit, the artilleryman is stymied by a wordy nurse, who tells him there is no room for him on the hospital train. “Make Miss Bates there, stop talkin’ or I’ll die,” he complains. Catching the educated reference to Emma, the head nurse finds a place for him on the train to safety.

Janine Barchas’s recent book, The Lost Books of Jane Austen, reproduces the beautifully grim illustrations of Kipling’s story from Hearst’s International Magazine in May 1924. Barchas also has an image of a combined printing of Pride and Prejudice and Northanger Abbey, which was one of 1.4 million books donated to the War Service Library in World War I.

In this program, the American Library Association (ALA) raised $1.7 million, purchased another 300,000 books, and shipped 109,403 books overseas. The ALA placed 117 librarians in the field, erected 36 libraries across 464 camps, and also distributed 5 million magazines to military personnel. Britain had a similar program of collecting books and magazines for the troops during World War I. Details of the British program have proven difficult to uncover, however.

Barchas found that the cheap editions of Austen’s novels helped develop Jane’s reputation during the 1800s. She found several rare copies of the war paperbacks and included them in her book. The image of Northanger Abbey, above by the headline, is from The Lost Books of Jane Austen and used with permission.

Cheap books—in this case, free—may have had the same effect on modern writers whose books were handed out to soldiers in WWI or WWII. Scribner’s produced only 25,000 copies of The Great Gatsby from 1925 to 1942, but 155,000 were given to the army and navy overseas during the war. Not coincidentally, F. Scott Fitzgerald enjoyed a boom in popularity after the war. The book is now considered a classic.

Military readers often expressed their thanks to authors in writing. Some authors received hundreds of thank-yous, with soldiers saying the books were the first they had ever read through in one sitting—or possibly read at all.

Austen’s stories of ordinary life in quiet country villages proved a respite to readers of the crashing struggle around them in Austen’s time. Her novels also reminded soldiers, then and later, of the life they were fighting for.

The novels might be said to have participated in the war directly. Some of Virginia Woolf’s copies of Austen’s books were reported to have been damaged during the Blitz, and a book dealer in London offered a first edition of Northanger Abbey and Persuasion at a discounted price “because it and other rare books had been water-damaged by firefighters battling an incendiary bomb.” The latter instance is recounted by Annette M. LeClair in the article “In and Out of the Foxholes: Talking of Jane Austen During and after World War II,” in the periodical Persuasions (issue 39). LeClair, who was investigating reader responses to Austen during WWII, concluded that she provided solace to the home folks as well as to the troops.

As much as the military owes Austen, though, the World War II anniversary should remind Janeites of all we owe the military. Jane Austen’s House, the most popular Austen site in the world, exists because of the sacrifice of Lt. Philip John Carpenter. He died at the age of twenty-two leading an attack in Italy in 1944. The Carpenter family purchased the cottage and gave it in trust to “all lovers of Jane Austen.” They had no deep connection to the author. But they were from Hampshire and wanted to honor their offspring. Philip is commemorated on a plaque near the entry.

One of the country’s many fallen sons gave rise to a sanctuary for one of the nation’s most beloved daughters.

—

The Marriage of Miss Jane Austen, which traces love from a charming courtship through the richness and complexity of marriage and concludes with a test of the heroine’s courage and moral convictions, is now complete and available from Amazon and Jane Austen Books.

The post Austen’s Words Soothe Soldiers, Home Folks appeared first on Austen Marriage.

September 18, 2020

What Reflection Brings the Thoughtful Writer–and Her Heroine

Last month, we examined Henry Austen’s comment about his sister Jane: “In composition she was equally rapid and correct.” We learned that Jane was probably neither. The somewhat limited evidence shows that she wrote at the average writerly pace of about 500 words a day. What she was, was a tireless reviser during all the years she was unable to publish. It was her unceasing revisions that taught her the art of fiction.

Though writing speed seems relatively constant across the field, the actual approach to writing varies. This month, we examine the approaches of different writers and see how Austen’s compositional strategy led to her writing breakthroughs.

Ernest Hemingway developed each chapter as fully as he could as he went. He revised extensively in later drafts. Kurt Vonnegut wrote paragraph by paragraph and would not move on until he thought the current paragraph was perfect. Vladimir Nabokov developed his novels on index cards, writing down key ideas, phrases, metaphors, etc. He would shuffle and add to the stack of cards until he had everything in perfect sequence. Only then would he begin to write each chapter in full.

The process varies, but the final output falls into the same range. There are some exceptions. Anthony Trollope is reputed to have written everything in full and from scratch, with little revision. This is how he produced a raft of novels that were good but not great. Charles Dickens wrote for serialization. The great discipline of deadlines generated a high output that also created the ragged quality that marks his work.

Judging from her unfinished novels, Austen seems to have sketched out the story first and returned for development. Virginia Woolf, in an essay in her book The Common Reader, identifies this technique by comparing the juvenilia and unfinished novels with her finished ones. In Austen’s younger or unfinished work, Woolf says, “her difficulties are more apparent, and the method she took to overcome them less artfully concealed.” Their lack of development, she says, shows that Austen lays out her facts “rather baldly” in the first draft and then goes “back and back and back” to cover them with “flesh and atmosphere.”

Austen has many skills within the writing arena: brilliant dialogue, brief but telling descriptions, psychological insight. Speed is not one of her abilities, nor is it a meaningful criterion. Good writing comes from good thinking. Good thinking requires—as Nabokov once said—not only second thoughts but third and fourth thoughts. It takes time to contemplate and reflect on human behavior to reach the depths that Austen explores.

A careful reader can find such ponderation at critical moments in Austen’s novels. One passage in Pride and Prejudice (Chapter 44 in modern editions) is particularly striking. The scene comes when, after several starts and stops, Elizabeth realizes that Darcy still must love her. Unlike other heroines of the day, she does not think, “Wow! He’s mine. Let’s get married!” Instead, she walks through what she’s feeling and tries to understand her own response. What is the nature of her turmoil—respect, gratitude, ego satisfaction, love? Notice how delicately Austen slides in: Elizabeth doesn’t allow herself to think immediately and directly of the man, nor even of his name.

“Her thoughts were at Pemberley this evening more than the last; and the evening, though as it passed it seemed long, was not long enough to determine her feelings towards one in that mansion; and she lay awake two whole hours endeavouring to make them out.”

Follow as Elizabeth processes multiple mental steps:

“She certainly did not hate him. No; hatred had vanished long ago.” She feels “respect created by the conviction of his valuable qualities”; he had “for some time ceased to be repugnant to her feeling.” She has moved into “somewhat of a friendlier nature” by the “amiable” disposition he had shown yesterday. But above all there was “gratitude, not merely for having once loved her, but for loving her still well enough to forgive all the petulance and acrimony of her … rejecting him, and all [her] unjust accusations.”

Instead, Darcy seemed “most eager to preserve the acquaintance” and to introduce her to his sister. Elizabeth attributes this to “love, ardent love,” and she thinks the “impression on her was of a sort to be encouraged. … She respected, she esteemed, she was grateful to him, she felt a real interest in his welfare; and she only wanted to know how far she wished that welfare to depend upon herself, and how far it would be for the happiness of both that she should employ the power, which her fancy told her she still possessed.”

Elizabeth’s recapitulation of her feelings builds through a series of reactions, each more positive: from her original hate to not hate; to a cessation of repugnance; to friendlier feelings; to respect and esteem; to gratitude; to concern for Darcy’s welfare; to wonder if she could make him happy—and he, her. What’s best, however, is this: Though she’s falling toward love, she hasn’t arrived—or is not able to admit she has. By not answering the question, the chapter tantalizes the reader to stay tuned.

It’s these kinds of psychological portraits that separate Austen from the pack. Perhaps this scene came out “rapid and correct” from the pen, without the need of a single blot. It is far more likely, however, that Austen went back repeatedly, adding more and more mental steps, more emotional responses. She revised, reordered, re-explained, as she put herself in Elizabeth’s head over and over again.

A serious writer could spend a week, or even a month, working and reworking these two or three pages to get the logic and emotion and phrasing just right. Austen likely revisited this important chapter multiple times over the years. However quickly she may have dashed off the first draft, such a scene comes only with effort and time.

Several authors have been credited with explaining how easy it is to write: All you do is sit down, open a vein, and bleed. To achieve this kind of exquisite result, Jane opened her veins and bled emotionally more than once along the way.

—

The Marriage of Miss Jane Austen, which traces love from a charming courtship through the richness and complexity of marriage and concludes with a test of the heroine’s courage and moral convictions, is now complete and available from Amazon and Jane Austen Books.

**

The post What Reflection Brings the Thoughtful Writer–and Her Heroine appeared first on Austen Marriage.

August 6, 2020

Jane Austen: Writing at the Speed of Thought

“In composition she was equally rapid and correct.”

This is what Jane Austen’s brother Henry had to say about Jane’s writing style in the “Biographical Notice” at the front of the combined Persuasion and Northanger Abbey. The short biography in the December 1817 publication informed readers that the author, to that point unknown, had recently died.

This brief comment has led to the general impression that Austen wrote rapidly and without much in the way of revision. Yet her few extant handwritten manuscripts show an author constantly revising, editing, inserting. People overlook the rest of Henry’s comment, which was that an “invincible distrust of her own judgement induced her to withhold her works from the public, till time and many perusals had satisfied her that the charm of recent composition was dissolved.”

Restated from the author’s perspective, Henry is saying that Jane understood how easy it is for a writer to fall in love with her own words as they flow from the pen—“the charm of recent composition.” The amateur asks for someone to critique her book and flies into a rage when the reader finds problems or suggests corrections. This is my baby—it’s perfect! In contrast, the professional comes back to the work to fix issues and develop material that contains the typical problems of “recent composition.” Austen returned to her works repeatedly in the years when she was unable to publish.

Undoubtedly, she found flaws every time she did and set out to fix them. She learned to be a professional by recognizing that, when the words grew cold, she could examine them with a fresh eye. The objectivity of “time and many perusals” enabled her to see, and revise out, any writing errors or plot problems she found.

Of course, the family did not want Austen represented as a professional, which is why Henry and Austen’s nieces and nephews spoke of her writing as if it were a casual pastime rather than hard labor. “Neither the hope of fame nor profit mixed with her early motives,” Henry wrote. Though her letters make clear she fought for compensation, Henry said that payment for Jane was “a prodigious recompense for that which had cost her nothing.” Nothing, of course, except a year or more of her time, countless reworkings until her eyes could no longer focus, and the nonstop anxiety of failure that comes with the writing life.

Her revisions show that Austen did not achieve “correctness” until after many changes. But how rapid was she? It is an axiom that writers should produce 500 words a day. This is not a high-end goal but more of a working average. The amount does not seem daunting—about a page and a half a day. At that pace, a writer can produce a book in a year. A writer in the flow can produce several thousand words a day for weeks at a time, but 500 words per day is a handy yardstick. Dry spells, false starts, plot stumbles, and other practical writing issues cut the daily average.

We have enough compositional dates to estimate Austen’s writing speed. Family records show that, with Persuasion, Austen took 19 days to revise one chapter and write another, effectively expanding one chapter into two. This came to roughly 9,000 words in 19 days, or about 475 words per day. This is not particularly fast; it indicates instead her effort at excellence. She probably produced a new draft in a week or ten days and spent about the same amount of time revising it to her satisfaction. (The image above, by the headline, shows her messy revisions of Persuasion; from the British Library.)

The unfinished Sanditon was similar. She worked on it for 50 days, producing 23,300 words, or 466 words per day.

Austen was seriously ill at this time, but her production during healthy years was actually lower. Her longer works would have required more time to develop complicated plots. Her 14-month stretch on the prodigious Emma comes in at 370 words per day. We don’t have precise creation dates for Mansfield Park in the overall span of 1812-14, but it would have been about the same. Even if we used something like 300 writing days a year instead of 365, the numbers would only bump up toward the “standard” of 500 words. Emma, for instance, would be more like 450 words per day.

Serious writing works on something like a half-life. Meaning, for a book of length, say 100,000 words, it would take six or seven months for the first draft; three or four months for the second draft; and perhaps two months for the third draft. Thus, about a year. (The schedule doesn’t include any additional time the writer has thought about the topic before beginning to write.)

For a book of 100,000 words, a year works out to an average of 555 words per day for the first draft (six months); and considerably less for the next two. Writers usually don’t add many words in the later drafts. They cut, they add, they revise, they rearrange, they edit. The result might be a final length that is 20 to 30 percent longer than the original.

Austen, then, did not write fast. But she wrote steadily, as can be seen in her output. According to Amazon, the average novel today is 64,000 words in length. Books in Austen’s day tended to be longer. Mansfield Park is 159,526 words. Emma is 155,887 words. Only 9 percent of novels in the English language are longer. Even the somewhat abridged Persuasion is 87,978, which is 10,000 words longer than Northanger Abbey.

Thus, in the eight Chawton years, the last two of which at least she was in failing health, Austen produced three new lengthy novels and revised her original three to some degree—how much is unknown. She also oversaw the production of four of her six books, which would take up several more months of her time. At one point in London, she was overseeing the production of Emma, the reissue of Mansfield Park, and the writing of Persuasion.

Austen was also caring for her desperately ill brother, Henry, and negotiating with her publisher, John Murray, because of Henry’s illness. During these same years, she was also reading novel-writing efforts by two teenagers: her niece, Anna, and her nephew, James Edward. She gave them writing advice in lengthy return letters.

Jane’s last three or four years of life are undoubtedly among the most productive of any serious writer in history. In composition she was not particularly rapid and probably not very correct, but in editing and rewriting she was as reflective as a philosopher and as dogged as a bill collector.

—

The Marriage of Miss Jane Austen, which traces love from a charming courtship through the richness and complexity of marriage and concludes with a test of the heroine’s courage and moral convictions, is now complete and available from Amazon and Jane Austen Books.

The post Jane Austen: Writing at the Speed of Thought appeared first on Austen Marriage.

July 8, 2020

Sifting Through Austen’s Elusive Allusions

Excellent researchers have divined many, many references and allusions that Jane Austen makes in her novels and letters. In his various editions of her works, R. W. Chapman lists literary mentions along with real people and places. Deirdre Le Faye’s editions of Austen’s letters include actors, artists, writers, books, poems, medical professionals, and others. Jocelyn Harris, Janine Barchas, and Margaret Doody have written extensively about people, places and things on which Austen may have based situations or characters. Some of Jane’s references are clear, some artfully concealed.

Yet we should be cautious about the great number of literary or historical finds uncovered by modern scholarship, because we often don’t know how many of these Austen knew herself. When a modern researcher cites an historical person from a couple of hundred years Before Jane, the marginal query must always be, “Did JA know this?” Many, she likely did. But probably not all. Maybe not even most.

Also, we don’t know how many references and allusions are tactical rather than strategic. Many authors include passing topical references with no other goal than to place the events of a novel in a particular time and place. A writer in 1960s America might show anti-war footage playing on a television. A current writer might mention a controversial American president or British prime minister. But unless a common theme directly connects the background references with the main storyline, these references are likely tactical rather than strategic.

Here, “tactical” means the reference has no profound meaning beyond the text. “Strategic” means an effort by the writer to establish a more general social, political, or historical context. A reference to a Rumford stove in Northanger Abbey, for example, is tactical, playing a newly invented appliance off the heroine’s expectations of dank passages and cobwebbed rooms. The naval subplot in Persuasion, on the other hand, is strategic. It incorporates not only the overall historical context but also the moral and intellectual contrast between the military men who have earned their wealth versus the wealthy civilians who are squandering theirs.

For many other items, it is difficult to determine the precise source. Education and literature in Great Britain then involved a small, fairly closed set of people. Limited common sources included the Bible, Shakespeare, and authors from the classical tradition. A common set of teachers came from the same small number of colleges using those limited sources. Everyone who admitted to reading novels drew on the same small pool of books.

It is conventional wisdom, for instance, that Austen took the phrase “pride and prejudice” from Francis Burney’s book Cecilia, where the capitalized phrase appears three times at the end. However, the literary pairing of “pride and prejudice” occurs elsewhere, including the writings of Samuel Johnson and William Cowper, two of Austen’s other favorite writers.

Even First Impressions, the original name for this novel, may have come from a common vocabulary. First impressions, and not being fooled by them, was a literary trope. In Ann Radcliffe’s The Mysteries of Udolpho, the heroine, Emily, and the secondary heroine, Lady Blanche, are warned not to rely on first impressions. This novel, shown above by the headline, is mentioned so often in Northanger Abbey that it is almost a character. The concept also arises in the works of Samuel Richardson. Austen may have borrowed from one of these specific authors. Or all the authors may have used a common literary vocabulary. Indeed, it was the recent publication of two other works with the title First Impressions that led Austen to change her title.

Another question is whether Austen knew the many layers of references that academics often point out. She apparently had free run of her father’s 500-book library, but we don’t know what it contained. As an adult, she had occasional access to the large libraries at her brother Edward’s estates at Chawton and Godmersham. How much she read of the classical material there, we don’t know.

Jane knew Shakespeare and the Bible well. She knew many poets, but would she have read a still earlier classical writer referenced by those poets? Did Austen know Shakespeare’s sources, which were often obscure Italian plays? We might be able to trace many connections back to the Renaissance or before, but she may have known only the immediate one before her.

Harris, Barchas, Doody, and others have given us multiple possible historical references to the name Wentworth in Persuasion. Austen might use the name to tie into this network of families and English history going back hundreds of years (strategic). Or she might use the name because of its fame in her day (tactical). The direct novelistic use is to contrast Sir Walter, who measures family names in terms of social status, with the Captain, who fills his commoner’s name with value through meritorious service. Sir Walter finally accepts Wentworth because of his wealth and reputation. He was “no longer nobody.” Yet the baronet can’t help but think the officer is still “assisted by his well-sounding name.”

Barring a letter or other source in which Austen states her purpose, we have no way of knowing whether Austen intended a broader meaning to “Wentworth” than its general fame. To some, the name in and of itself establishes the broad historical context. To others, it would take more than the three or so brief references to Wentworth, as a name, to show that Austen means to establish a meaningful beyond-the-book purpose.

Another consideration is that, cumulatively, commentators have found an enormous number of supposed references and allusions in Austen. Could a fiction writer, with all the work required in creating, writing, and revising a novel, have the time and energy to find and insert a myriad of outside references and allusions? Could a writer insert many references without bogging down the work?

Every writer who has tried her hand at historical fiction, for example, knows that too much history can overwhelm the novel’s story, leaving characters standing on the sideline to watch events pass by. Every external reference creates extra exposition that creates the danger of gumming up the plotline. It might also create a new emotional tone at odds with the characters’ situation or other complexities that must be resolved. We can’t underestimate the extra work for an author who already has her head full of practical book-writing issues—plot and character development—that need to be kept straight.

Finally, writers often plant things for no other reason than fun. In Northanger Abbey, John Thorpe takes Catherine Morland for a carriage ride early in the story. Barchas points out that he asks her about her relationship with her friends, named Allen, at just the point where their carriage would be driving past Prior Park, the home of Ralph Allen. This was the stone mogul who helped build Bath.

Austen does not explicitly call out the family home. Readers who know Bath’s geography and make the connection to the wealthy masonry clan get an extra chuckle. Readers unfamiliar with the geography, or with the wealthy Allen descendants, would not suffer from a lack of understanding.

All a reader needs to know is that Thorpe thinks the Morlands are connected to a very wealthy family, when in fact their friends named Allen are only modestly well-to-do. Thorpe’s misunderstanding drives the book’s plot. Very likely, all Austen wanted with the Prior Park allusion was to give a wink to the bright elves reading her book.

Thus the author may mean one thing, while later analysts might find something beyond what the writer ever intended. In Mansfield Park, for instance, Henry Crawford reads Henry VIII aloud. A broad interpretation might connect the attitude of the rogue Henry Crawford with the attitude of the rogue Henry VIII: Women and wives are interchangeable, expendable, to be taken at whim and tossed away at whim. Or perhaps the name Henry is nothing more than a tip of the hat to Jane’s favorite brother, Henry.

Austen may well have intended multiple levels of interpretation. But note that she has Henry Crawford himself say that Shakespeare is “part of an Englishman’s constitution … one is intimate with him by instinct.” Edmund Bertram agrees: “We all talk Shakespeare, use his similes, and describe with his descriptions.”

Others may feel that Austen deliberately weaves in as many references as she can. One must imagine her writing with a variety of concordances stacked to the ceiling. But she indirectly tells us of a different approach. One is “intimate” with Shakespeare by “instinct.” She knew the Bard and other writers in depth, and the references come out organically. Much more than by design, this fine writer pulls what she needs from history by “instinct.”

—

The Marriage of Miss Jane Austen, which traces love from a charming courtship through the richness and complexity of marriage and concludes with a test of the heroine’s courage and moral convictions, is now complete and available from Amazon and Jane Austen Books.

The post Sifting Through Austen’s Elusive Allusions appeared first on Austen Marriage.

June 11, 2020

Frankenstein in Austenland

News alert from Bath: Frankenstein is coming to Austenland.

No, I’m not talking about another mashup between a Jane Austen novel and a horror thriller but rather about plans afoot in the city of Bath to create a museum honoring Mary Shelley’s creation.

Casting about on the internet while researching Jane Austen, I often find such interesting topics that deserve notice, though not necessarily a blog onto themselves. The Frankenstein story is one of them. After it, I’ll serve up a few other dishes related to women and writing.

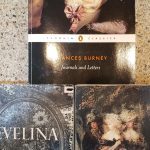

First up is that the city of Bath, hitherto the sole province of Austen, is opening a museum dedicated to Mary Shelley and her book Frankenstein. (Image above is from my mid-1960 copy of the novel.)

Shelley, the daughter of feminist firebrand Mary Wollstonecraft and soon-to-be wife of the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, lived in Bath’s Abbey Churchyard when she wrote the novel. Frankenstein is one part science-fiction novel—considered the first—and one part traditional gothic. (There is a pun in there somewhere involving body parts.)

Austen’s own Northanger Abbey is set in Bath and parodies the gothic novel, which was popular when Austen wrote the novel in the early 1800s but not when it was published in 1817.

Many of the most popular books of the nineteenth century, however, had a gothic origin: Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818); Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights (1847), in which a forbidding castle is replaced by a remote house on a windswept heath; Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre, (1847), which features the gothic motif of the wronged woman held prisoner in a frightening house; Wilkie Collins’ Woman in White (1865), considered the first mystery novel and this time with an innocent woman locked in an insane asylum; and Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897), which takes us back to frightful castles in remote locales.

Frankenstein arose as the consequence of a competition among Mary, Percy, and the poet Lord Byron, to see who could write the best horror story. The German setting likely came from the couple’s travels along the Rhine in 1815. Mary’s museum will be just down the street from the Jane Austen Centre on Gay Street. Perhaps the new museum will create a wax figure of the monster to meet the wax figure of Jane.

Moving from a city street in Bath to one in London, here’s a story involving five iconic women writers who all lived in the same square but at different times. The five wrote on radically different topics, ranging from poetry to serious novels to detective fiction to anthropology to politics. Some came at the start of their careers; some came near the end. But during two world wars, Mecklenburgh Square played a major role in their lives and writing.

In a period of a pandemic, we can find out why modern readers are drawn to Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway. Though the novel presents ordinary life as the title character prepares for a party, one undercurrent involves the recent worldwide flu pandemic. Woolf’s mother died because of an earlier influenza, and Woolf herself suffered from several flu infections from 1916 to 1925.

Finally, back to Austen. Most readers know that Jane was not the shining female literary star of her age. She was eclipsed by Fanny Burney, whom we discussed last month, and by Maria Edgeworth, who wrote realistic but moralistic novels. Austen praises Edgeworth in her books and letters and even sent her a copy of Emma. Edgeworth in turn offered different opinions of Austen’s novels. Linda Bree talks about the connections between the two authors.

—

The Marriage of Miss Jane Austen, which traces love from a charming courtship through the richness and complexity of marriage and concludes with a test of the heroine’s courage and moral convictions, is now complete and available from Amazon and Jane Austen Books.

The post Frankenstein in Austenland appeared first on Austen Marriage.

May 14, 2020

Fanny Burney: Writer of Her Time

Fanny Burney was the female writer before and during Jane Austen’s life. Both in popularity and literary regard, she stood astride the Regency era as the Colossus stood astride the harbor of Rhodes. She published her first novel, Evelina, when Jane Austen was three years old, hit her publishing peak as Jane was beginning her serious writing, and continued to live and work for another two decades after Austen’s death.

To ensure the proper level of respect, some editors insist that we call her “Frances” rather than “Fanny,” the name she used all her life. Evidently, no one will take her seriously as Fanny but Frances will garner immediate intellectual respect. You’d think her complex writing style, modeled on Dr. Johnson, would be enough for anyone to take Burney seriously. But, here, we digress. …

Austen called Burney, who married a French officer to become Madame D’Arblay, “the very best of the English novelists.” In tracking Jane’s surviving correspondence, we can see her tracking Burney’s career. At the age of twenty, Jane subscribed to the purchase of Burney’s third novel, Camilla.

Two months after its publication in July 1796, Austen references Camilla in three successive letters, including the comment that an acquaintance named Miss Fletcher had two positive traits, “she likes Camilla & drinks no cream in her Tea.” Camilla is mentioned in the discussion of novels in Northanger Abbey. Jane’s annotated copy of Camilla is now in the Library of the Victoria and Albert Museum.

More interesting is a possible indirect but personal connection between the Austens and the D’Arblays. A relative, who likely encouraged the Austens to subscribe to Burney’s novel, was Mrs. Cassandra Cooke. She was first cousin to, and a contemporary of, Jane’s mother. The Cookes lived across the road from Burney and her husband for four years and nearby for several more.

Though the two authors never met, Jocelyn Harris writes in an article that Mrs. Cooke was probably a “direct source of information” about Burney to Austen. In her book Satire, Celebrity, and Politics in Jane Austen, Harris also finds a number of connections between scenes and characters in Austen’s fiction and Burney’s novels and life. Harris proposes that Mrs. Cooke may have been the source for the biographical anecdotes about Burney.

In addition to her novels, Burney wrote plays, most of which went unproduced, and was active at court. From 1786 to 1791 she was “Second Keeper of the Robes” to Queen Charlotte, and she dedicated Camilla to her. During the Napoleonic wars she was trapped for a decade in France. Though her husband was a military man and patriotic Frenchman, the couple detested the violence of the French Revolution and the dictator that followed. She was able to slip out of France when her son was a teenager to keep him from being conscripted into Napoleon’s army.

When Napoleon returned from exile in Elba to reclaim his throne, this time her husband fought against him on the side of the allies and was wounded in battle, before Waterloo ended Napoleon’s career a final time. After the war, the D’Arblays settled in Bath near relatives. Many French emigres had settled there during the war.

Two hundred years later, Burney’s position as Literary Superstar and that of Jane the Obscure has reversed. Burney is still read, and The Burney Society exists to promote her life and works. Yet most of the interest today relates to her diaries and journals, which show us the private thoughts of a sensitive, articulate woman about her long and eventful life. They record what it was like for an intelligent, vivacious, politically aware woman of the age. The also record her personal travails, including her description of undergoing a mastectomy in France—without anesthesia.

Burney began her diaries as a teenager. In an early entry, she tells of an earnest but not very pleasant fellow who fell for her on their first meeting. She asks her family how to get him to leave her alone. They instead encourage another visit. Burney writes in her diary something right out of (write out of?) Austen: that she “had rather a thousand Times die an old maid, than be married, except from affection.”

Today, few would put Burney in the same class as Austen as a novelist. Many Burney characters are extreme, her plots at times involve wild coincidences, and her language is enormously complex. What follows is a simple but representative example in the difference of style. The first is Austen’s dedication to the Prince Regent at the beginning of Emma. The next is Burney’s dedication to Queen Charlotte at the beginning of Camilla.

Austen’s, printed in capital letters and in large type to fill the page:

“To his Royal Highness the Prince Regent, this work is, by his Royal Highness’s permission, most respectfully dedicated, by his Royal Highness’s dutiful and obedient humble servant.”

Burney’s, set in type a little larger than normal, addresses the queen directly:

“THAT Goodness inspires a confidence, which, by divesting respect of terror, excites attachment to Greatness, the presentation of this little Work, to Your Majesty must truly, however humbly, evince; and though a public manifestation of duty and regard from an obscure Individual may betray a proud ambition, it is, I trust, but a venial—I am sure it is a natural one. In those to whom Your Majesty is known but by exaltation of Rank, it may raise, perhaps, some surprise, that scenes, characters, and incidents, which have reference only to common life, should be brought into so august a presence; but the inhabitant of a retired cottage, who there receives the benign permission which at Your Majesty’s feet casts this humble offering, bears in mind recollections which must live there while ‘memory holds its seat,’ of a benevolence withheld from no condition, and delighting in all ways to speed the progress of Morality, through whatever channel it could flow, to whatever port it might steer. I blush at the inference I seem here to leave open of annexing undue importance to a production of apparently so light a kind yet if my hope, my view—however fallacious they may eventually prove, extended not beyond whiling away an idle hour, should I dare seek such patronage?”

Austen was no fan of the Prince Regent, and her publisher probably prodded her into a sufficiently proper flourish. Yet even doubled, her dedication would barely run 50 words. Burney’s dedication runs 216 words—and the excerpt does not include all of it.

This gushing pipe of words is not just an instance of royal flattery. The entire 900-page novel strains under the load of such verbiage. Burney’s first and most successful novel, Evelina, written in the epistolary style, was a contrast. The letters by Evelina are as sharp and funny as anything Elizabeth Bennet ever said. Everyone else, however, writes in a ponderous style that came to dominate Burney’s third-person novels. Wanting to be taken seriously, Burney followed the “serious” style that “real literature” of the eighteenth century required. She was a writer of her time.

—

The Marriage of Miss Jane Austen, which traces love from a charming courtship through the richness and complexity of marriage and concludes with a test of the heroine’s courage and moral convictions, is now complete and available from Amazon and Jane Austen Books.

The post Fanny Burney: Writer of Her Time appeared first on Austen Marriage.

April 16, 2020

Get out the Popcorn. It’s Time for Movies!

Enough people had commented on the two new Jane Austen adaptations earlier this year that at first I decided not to. However, lots of people are binge-watching shows during these plague weeks. The movie Emma has moved directly online, where it’s available for a fee; and the Sanditon series is still available on demand. Seems like now’s a good time to provide a critique.

Emma. It’s fun. It features a lot of Austen’s dialogue, which is usually better than what is substituted in many scripts. It plays the comedic scenes really well. In the novel, Emma’s self-importance and matchmaking mistakes are balanced by her personal warmth, her care for her ailing father, and her general good works. No room for the warm side in the movie, leaving Emma, played by Anya Taylor-Joy, as a person who is sharper and cooler and funnier than in the book.

Mr. Knightley is an interesting casting choice. He’s supposed to be tall. Played by Johnny Flynn, he’s not, but he otherwise fills the role admirably. Enough humor to balance the gravitas. He’s not as remote as the original can seem. Flynn also looks too young, but he’s thirty-seven, the same age as Austen’s Mr. Knightley. Taylor-Joy is just twenty-three, compared to the book’s twenty-one. It’s nice when the ages of the actors match the ages in the book.

Bill Nighy is too spry for the father in the novel but good for his role here, a couple of brief comedic turns. Miranda Hart as Miss Bates is terrific as a prattler with the build of a football player. The other players check the boxes for their roles.

My one problem with Emma casting continues. Harriet Smith is supposed to be drop-dead gorgeous and have “soft blue eyes.” Harriet’s beauty and good nature offset her dim wit and questionable birth, making it possible for her to move up socially. So Emma thinks. But in movies, no director wants another actress to compete with Emma’s glow. Consequently, Harriet is usually dressed down and drab. So it is with Mia Goth, who is “pretty” in Austen terms, but no beauty. She also has brown eyes.

According to experts, the costuming is the best to date of any Austen film. In addition to being beautifully done, the styles are correct for the time. Often, the dresses will be a generation or two out of date or premature. Worth watching for the costumes alone. Even my wife, who’s not a fan of the Empire style, praised the looks.

The only thing at odds with the novel is the portrayal of the marriage between Knightley’s brother and Emma’s sister. In the book, they’re just busy with a bunch of kids, and the brother doesn’t cater to the whims of Emma’s father the way Knightley does. In the movie, the couple squabbles constantly. They don’t occupy much screen time, but it’s unclear why the change was made. Perhaps because they didn’t have much else to do. Their role is minor in the book and even less in the film.

The only other non-canonical element is that Emma gets a nosebleed at a certain point. Some people complain. It didn’t bother me. It’s a physical manifestation of her emotional state.

If you generally like period films, you’ll enjoy it. If you’re an Austen fan, it’ll be a hoot.

Sanditon. This is Andrew Davies’ effort to flesh out Austen’s barely begun novel of that name. Davies is highly regarded for his 1995 Pride and Prejudice BBC adaptation starring Jennifer Ehle and Colin Firth. It’s probably the most popular video presentation of any Austen novel. He’s done dozens of other period movies in his long career, and his Sanditon series was awaited with great anticipation.

Consensus to date is that it was a nice Regency miniseries (eight shows) but it wasn’t a Jane Austen-like continuation. Too modern. Too much bodice-ripping. Several scenes contain overt sexuality, and one major taboo seemed to have been broken. These things didn’t bother me. Austen has naughty bits, they’re just always offstage.

I just don’t think Davies did much with Austen. The story is of the Parker family, which is trying to create a hot new beach resort from a sleepy old village. Austen got no further than laying out the setup and introducing the main characters. We can probably guess that Charlotte Heywood, played by Rose Williams, and Sidney Parker, played by Theo James, will be the happily-ever-after pair, but we don’t know.

Rose Williams, as Charlotte Heywood, has the busiest and most nuanced role, but she can’t overcome the tepid script. (ITV)

Rose Williams, as Charlotte Heywood, has the busiest and most nuanced role, but she can’t overcome the tepid script. (ITV)Charlotte is in many scenes, and Williams has the most varied set of emotional reactions and responses to work with. She’s plucky like Elizabeth Bennet in Pride and Prejudice but has some of the softness and trusting nature of Lizzie’s older sister Jane. Williams carries off the country day dresses with confidence and the ballroom gowns with bewitching innocence.

As I’ve written before, the wildcard is that we don’t know what Austen intended for Miss Lambe, a wealthy “half-mulatto” teenage girl who begins as the target of the avaricious Lady Denham and her nephew Edward. Would Miss Lambe be an exotic piece of the background? Would she become a Harriet to Charlotte’s Emma, a secondary character any sympathetic reader would care about? Or—surprise—is she the actual heroine? Unknown. Davies gives her the sidekick role, though her situation is so constrained that the character, played by Crystal Clarke, often has nothing to do but look or speak unhappily.

Davies also introduces another young swain who isn’t in the book. Is he the real hero and Sidney Parker a feint? Enough other male characters exist, and enough is unknown about the direction of the novel, that any of them could have been converted into the role taken by Young Stringer, played by Leo Suter. He’s the most likable man and the most compatible with Charlotte, it seems. But adding still another character is unnecessary.

Davies repeats motifs from other novels. Early on, Charlotte takes charge after an accident, very much like Anne in Persuasion. It seems as though there’s an incident in every installment based on another book. Davies’ intent was to pay homage to Austen, but it feels like repetition. Davies seems to want to out-Darcy Darcy in his presentation of Sidney Parker. Despite James’s efforts, Parker is more unlikeable than unreadable, which was ultimately the case with Darcy.

I’ll leave it to viewers to point out the many other similarities to Austen’s other works. Too often, the characters seem to know they’re reenacting rather than acting, with lackadaisical results.

Dialogue is part of the problem. Charlotte and Parker have some wicked exchanges, the first one at a ball. But other times, Parker is just rude rather than witty. Each episode is followed by comments by the actors and by Davies about the series. In one, Davies talks about how easy it was to write the dialogue. I thought, yeah, that’s because it’s easy to write bad dialogue. Very little of it had anything resembling Austen’s sparkle.

One couple that did work was Esther Denham and Lord Babington. Esther is (we assume) a minor character in the novel. Lord Babington is a new creation. Their back-and-forth is interesting because Esther, played by Charlotte Spencer, is not as cold and heartless as she seems, and Babington, played by Mark Stanley, is smarter, more thoughtful, and more determined than he seems. Their story being original, Davies comes up with original material. Where other couples lack energy, Esther and Babington breathe fire. Well, Esther does. Lord Babington proves worthy in his battle with the dragon.

Finally, Davies left a few matters to be tidied up. However, the British broadcaster, ITV, said it did not plan to renew the franchise. It seems unlikely that the U.S. partner, PBS, might find someone else to carry on. The series got mixed reviews. Like the novel, and like the town of Sanditon itself, the miniseries ends up feeling unfinished too.

—

The Marriage of Miss Jane Austen, which traces love from a charming courtship through the richness and complexity of marriage and concludes with a test of the heroine’s courage and moral convictions, is now complete and available from Amazon and Jane Austen Books.

The post Get out the Popcorn. It’s Time for Movies! appeared first on Austen Marriage.

March 18, 2020

Jane Austen, Contagions, & the Danger of Doubling

It has been so long since a disastrous contagion swept through the Western world that most of us have forgotten how deadly contagious diseases are. The scariest in my lifetime was polio, because the disease could cripple as well as kill. I remember lining up at the local high school with all the other kids to get the first polio vaccine.

In 1969, the Hong Kong flu swept through my college, leaving me and many others—all healthy young people—bedridden for more than a week. The Spanish flu in 1918 killed between 25 and 50 million people—more than all the deaths caused by the violence of World War I.

Historically, things were worse. Yellow fever took nearly half of all the British who went to the West Indies. The disease killed Tom Fowle, the fiancé of Jane Austen’s sister Cassandra, on a military ship cruising in the Indies. So many white men died in the region of “yellow jack” that the British military purchased 13,400 enslaved blacks to fill out their ranks. The men were promised freedom at the end of their service.

Jane and Cassandra nearly died from typhus as children. The mother of their cousin did die from it when she came to care for the two girls and her own daughter, who was also infected. Jane also contracted whooping cough (pertussis), and probably other diseases. None of Austen’s novels deal with a major epidemic, though they would have broken out regularly. Emma (above, by headline), would have been in particular danger because of her regular visits to villagers suffering “sickness and poverty together.”

Jane Austen survived typhus, whooping cough (pertussis), and likely other serious contagious illnesses in her life.

Jane Austen survived typhus, whooping cough (pertussis), and likely other serious contagious illnesses in her life.People should be aware that Native Americans were largely wiped out by pestilence brought to the New World by Europeans. The only reason the New World could be settled en masse is that upwards of ninety percent of its original inhabitants had died since the first Spanish explorations. Smallpox was one of the most devastating. Native Americans had no resistance. Smallpox might kill 30 percent of an English village. It could wipe out most of a North American village.

Smallpox vaccinations began to occur after Edward Jenner’s proof that the method worked. Mrs. Lefroy, one of Austen’s mentors, led a campaign to vaccinate children in Hampshire in the late 1790s. The practice remained controversial, though. Jane’s brother Edward did not have his family vaccinated until 1810.

Some diseases no longer frighten us because vaccines have largely eliminated them. During Jane Austen’s day, measles killed as many people as smallpox or typhus, or it weakened individuals enough that they succumbed to others. In the early 1500s, measles in Cuba killed two-thirds of the people who had survived smallpox and killed half the people in Honduras.

Despite the development of modern vaccines, the high contagion rate by measles makes it a continued scourge. Measles, which is twice as infectious as the flu and covid-19, caused 134,200 deaths in 2015, according to the World Health Organization.

In avoiding vaccines, people have counted on “herd immunity” protecting them—because the rest of us were vaccinated, the risk of measles spreading was almost nil. Now, however, so many people have used the same ploy that gaps have opened in herd immunity. Refusal to vaccinate has led to a return of the disease in the U.S.; deaths rose from 37 people in 2004 to 667 people in 2014, the last year for which reliable numbers are available. Seven children died of pertussis in 2016, despite the availability of a vaccine.

Children under the age of five have always been the most likely to become infected and to die from measles and pertussis. Older people are more likely to die of the flu and related infections. People beyond the age of sixty have weaker immune systems and are more likely to have developed other conditions that render them more susceptible.

This recapitulation brings us to the current covid-19 pandemic. Health authorities have urged serious action, including shutting down all but the most critical activities and self-isolating to avoid the spread. Some people are claiming that these actions are too extreme. If the pandemic peters out, no doubt a few naysayers will claim the whole thing was an overreaction.

Truth is, if we do all the right things, the naysayers to be right: the pandemic will fade away. They’ll be wrong, however, about the reason. It’s not that fears of the disease were overblown. It’s that we took the steps to break the power of doubling.

Contagions spread in predictable ways. Worldwide, covid-19 cases are doubling every five days as one person infects several more. In Italy, cases are doubling every three days, which is why they have been overwhelmed. That’s why we’ve seen diseases in the past that have killed large parts of the population.

But if you have only 20 or 30 cases, you figure the crisis will be far down the road. That’s what the naysayers assume. They don’t recognize the danger of doubling. If you put one grain of sand in the first square of a chessboard, and double it to two in the next square, and double that to four in the next, and so on across the board … by the time you’ve gotten to the last square, you’ll have more grains of sand than exist on the earth!

If the U.S. has 4,000 cases today, and the cases double every five days through a normal spread through the population without any preventive measures, we’ll have 32,000 cases by the end of the month, 256,000 on April 15, a million cases by April 25, and 16 million cases by May 15. (The official U.S. number jumped from 3,400 to 5,200 overnight. I’m using 4,000 as a convenient base.)

At 16 million cases, one to two million people will require hospitalization. That number overwhelms our hospital beds, ventilators, and other infrastructure. Ventilators are the critical device for compromised lungs. The load also overwhelms doctors, nurses, and other care providers. (See Italy.)

Very likely, the current number of U.S. cases is much higher. One county in California just had its first two deaths. With a mortality rate of 2-3 percent, this means about 100 people are infected. Yet the official county number is only 20. If this is typical countrywide, then the current U.S. number is closer to 20,000 than 4,000-5,000. This means 80 people could be wandering around in that one county, unknowingly infecting others, while 15,000 people might be doing the same nationwide.

We don’t have good numbers because, for inexplicable reasons, the government did not authorize private labs to create testing kits all the way back in January. We’re only just now getting a fair number in the field to know what the correct caseload might be. We could be hitting the “knee of the curve,” when the numbers shoot up into the millions, even sooner than mid-May.

The pandemic affects more than people with the disease. People needing treatment for other serious diseases, including the flu, may have no care available. If you need emergency surgery, an acquaintance pointed out, your doctor likely will have been working round the clock for weeks. Your surgical station might be a tent on the front lawn. The hospital might be low on antibiotics or other meds. And, of course, you’ll be surrounded by people carrying a deadly disease.

There’s only one way to break the power of doubling: end the physical connections between people that enable the disease to spread. Doubling once every five days results in a number 64 times as large as doubling once a month. By separating ourselves, we can flatten the curve, spread out and reduce the number of cases, keep the peak below the level of “hospital collapse,” benefit from a possible summer falloff, and hang on until a vaccine arrives in 12 to 18 months.

If we do bring the pandemic to a halt, let’s be wise enough to know why it stopped. Not because fears were overblown but because we acted aggressively when the numbers were still low. Now is when we can make a difference. Let’s do the right thing—which is to remain as far as we can from as many people as we can until we have a handle on this thing.

Anyone for reading a great Austen novel in isolation under a tree?

—

The Marriage of Miss Jane Austen, which traces love from a charming courtship through the richness and complexity of marriage and concludes with a test of the heroine’s courage and moral convictions, is now complete and available from Amazon and Jane Austen Books.

The post Jane Austen, Contagions, & the Danger of Doubling appeared first on Austen Marriage.