Coleman Hughes's Blog

July 16, 2025

Socialism isn't Making a Comeback. It Never Went Away.

Zohran Mamdani’s surprising victory over Andrew Cuomo in New York City’s democratic mayoral primary has provoked lots of theorizing about why socialism is rising in popularity among the youth. Tyler Cowen argues that American society has become more negative overall, and that young people are therefore hungry for any change from the status quo. I think there’s truth to that. Others have argued that it’s because the price of homes has risen faster than incomes. More on that later.

My theory is simpler: it’s not that young people are suddenly getting into socialism, it’s that older people were turned off to it for specific, contingent reasons. And now it is just returning to its default level of popularity.

Coleman’s Corner is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Socialism is an inherently popular message. It’s analogous to the idea of the afterlife. The notion of an afterlife is part of almost every religion, including religions that sprang up independent of one another. We love it because we fear (and cannot accept) death. So from the POV of human psychology, the question is not why people like the idea of an afterlife; the question is why atheists reject it.

Similarly, socialism promises to take from the rich and give to the poor. Which is to say, it promises not only “free stuff,” but also a more equal society. Critics of socialism often highlight the first half without realizing the importance of the second. The human instinct for fairness is deep-seated and evolutionarily ancient. Parents notice how naturally it comes to their children to complain that their sibling got more than they did. It doesn’t need to be taught.

Tocqueville was on to something when he argued that the idea of equality had a deep magnetic pull that (ironically) would only strengthen as American society became more equal. “Take from the rich and give to the poor”, like the afterlife and major thirds, sounds extremely good to the human ear.

Consider that since WWII, socialism has won elections fair and square––too many to tally here––on every inhabited continent in situations too diverse for its appeal to be explained by the particular circumstances of any given country. And even in cases of violent takeovers and civil wars, communists several times defeated rival groups by winning the hearts and minds of the peasants with their superior messaging.

So the question is not why young people like socialism. That requires no explanation. The real question is why older people don’t.

For some groups, the answer is obvious: They lived through socialism and saw it ruin their countries. Talk to anyone of a certain age from Cuba, Venezuela, or Eastern Europe, and you will often find that they don’t just dislike socialism; they hate it. They are totally immune to its charms.

For Americans, my theory is that those over ~55 years-old lived through the last days of Cold War, the collapse of the Soviet Union, the undeniable victory of capitalism over socialism/communism, and the roaring ‘90s. If that is a part of your individual political memory, then it is hard to hear “socialism” as having anything but a negative connotation––even if it’s more mildly negative than for a Cuban refugee.

Let’s look briefly at the other theories. One is that the price of housing has risen faster than incomes. So Gen Z may be able to afford Netflix and Spotify (and yes, it would have cost thousands to get all that content in the ‘90s!), but they still can’t buy a home like their parents and grandparents could. That matters.

But if that’s the source of discontent, then why the turn towards socialism as opposed to, say, abundance, which actually has evidence-backed solutions for housing affordability? I submit that it’s because socialism has an inbuilt messaging advantage over deregulation, even if deregulation has a much better track record.

Another theory is that kids-these-days just aren’t educated about economics. Again, true enough. But I don’t think this is relevant given that our parents generation was not all that Econ-literate either. After all, who was Bryan Caplan writing about in his great 2007 book The Myth of the Rational Voter? Not Gen Z!

To sum up, I’m arguing that socialism is by default a winning political message for reasons having to do with human nature––except in cases where people have lived the reality of socialism’s failure firsthand. “Take from the rich and give to the poor” is simply hard to compete with. If I’m right, then we can expect the popularity of socialism to rise as generational turnover unfolds––until it reaches a tipping point where the young experience the reality of its failures firsthand and mount a backlash.

There’s no reason to be fatalist about this though. I think "Abundance” is a great left-coded alternative to socialism. But it has to find a way compete with one of the oldest and most successful messages in (post-Industrial Revolution) politics.

Coleman’s Corner is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

January 26, 2025

The End of DEI

Last February, my book, The End of Race Politics: Arguments for a Colorblind America was published. In it, I argued that color blindness—the principle that people should be treated without regard to their race—should guide American public policy. For this, I was called a “charlatan” by Sunny Hostin on The View.

I did not foresee that less than a year later Donald Trump would become president again, and that upon taking office, he would end decades of race-based presidential directives and with the stroke of his Sharpie adopt my call for racial color blindness. As Trump put it in his inauguration address: “We will forge a society that is color-blind and merit-based.”

Coleman’s Corner is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Trump’s Executive Order 14171 is titled Ending Illegal Discrimination and Restoring Merit-Based Opportunity. It describes how vast swaths of society, including the “Federal Government, major corporations, financial institutions, the medical industry, large commercial airlines, law enforcement agencies, and institutions of higher education have adopted and actively use dangerous, demeaning, and immoral race- and sex-based preferences under the guise of so-called ‘diversity, equity, and inclusion’ (DEI).”

In response, Trump has ordered the executive branch and its agencies “to terminate all discriminatory and illegal preferences, mandates, policies, programs, activities, guidance, regulations, enforcement actions, consent orders, and requirements.”

That is a lot of preferences and mandates. Trump’s executive order accurately describes the enormousness of the DEI bureaucracy that has arisen in government and private industry to infuse race in hiring, promotion, and training. Take, for example, the virtue-signaling announcements made by big corporations in recent years—such as CBS’s promise that the writers of its television shows would meet a quota of being 40 percent non-white.

And so, we will now see what federal enforcement of a color-blind society looks like. We’ll certainly see how many federal employees were assigned to monitor and enforce DEI—Trump has just demanded they all be laid off.

The most controversial part of this executive order is that it repeals the storied, 60-year-old Executive Order 11246, signed by President Lyndon Johnson in 1965. Johnson’s original order mandated that government contractors take “affirmative action” to ensure that employees are hired “without regard to their race, color, religion, or national origin.”

The phrase affirmative action, however, has come to have a profoundly different meaning for us than it did during the 1960s civil rights era. Back then, it simply meant that companies had to make an active effort to stop discriminating against blacks, since antiblack discrimination was, in many places, the norm. Only later did the phrase come to be associated with the requirement to actively discriminate in favor of blacks and other minorities.

One of the great ironies of affirmative action is that it was not a Democrat but a Republican president, Richard Nixon, who did more than anyone to enshrine reverse racism at the federal level by establishing racial quotas. According to the Richard Nixon Foundation, “The Nixon administration ended discrimination in companies and labor unions that received federal contracts, and set guidelines and goals for affirmative action hiring for African Americans.” It was called the “Philadelphia Plan”—the city of its origin.

For the first time in American history, private companies had to meet strict numerical targets in order to do business with the federal government. Philadelphia iron trades had to be at least 22 percent non-white by 1973; plumbing trades had to be at least 20 percent non-white by the same year; electrical trades had to be 19 percent non-white, and so forth.

In the intervening decades, this racial spoils system has not only caused grief for countless members of the unfavored races—it has also created incentives for business owners to commit racial fraud, or else to legally restructure so as to be technically “minority-owned.” As far back as 1992, The New York Times reported that such fraud was “a problem everywhere”—for instance, with companies falsely claiming to be 51 percent minority-owned in order to secure government contracts. In a more recent case, a Seattle man sued both the state and federal government, claiming to run a minority-owned business on account of being 4 percent African.

For progressives, Trump’s repeal of LBJ’s 1965 executive order is being framed as a reversal of Civil Rights–era gains. In covering the repeal, Axios reminds readers that “Segregationists during Johnson’s time opposed the executive order.” This framing makes sense only if you omit the changed meaning of affirmative action over time. In context, the segregationists of the 1960s believed in a race-based society and wanted to exclude black people from opportunities, whereas today, Trump is opposing racial mandates. They were against color blindness; Trump is for it.

Trump’s executive order gets closer to the original intent of the civil rights movement than today’s DEI policies. During the Senate debate over the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the bill’s lead sponsor, Senator Hubert Humphrey, famously promised that if anyone could find any language in the Civil Rights Act that required preferential hiring based on percentages or quotas, he would eat the entire bill page by page. In the twenty-first century, it’s today’s progressives who would be the ones chewing.

But Republicans have soul-searching of their own to do. Their presidents have been complaining about, and campaigning against, affirmative action since the Reagan era at least. But Trump is the first president to actually do anything about it. Affirmative action has long been unpopular with the public, which is why it lost two separate referendums in the solid-blue state of California. And it’s also why the 2023 Supreme Court ruling that struck down affirmative action in college admissions was met more with resignation than with protest on the left. Still, Republican presidents have been too risk-averse to take straightforward steps to roll it back.

In one sense, Trump is simply riding an anti-DEI wave that he cannot claim credit for. For instance, he could have done this in his first term, but like every Republican since Nixon, he chose not to.

Yet in another way, Trump is demonstrating one of his strengths as a leader: the ability to stop procrastinating and take calculated risks. We saw him exhibit this quality when he moved the American embassy in Israel from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem. And we see it today, with his long-overdue rollback of an unpopular DEI establishment.

While most states still have independent race-based policies that are not directly affected by Trump’s directive, this is an important moment in the history of American race relations, and a special moment in the career of this writer: Regardless of what happens, it is not every day that you get to see your ideals enshrined as the law of the land.

Coleman’s Corner is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

December 18, 2024

My Mom—and the Case for Assisted Death

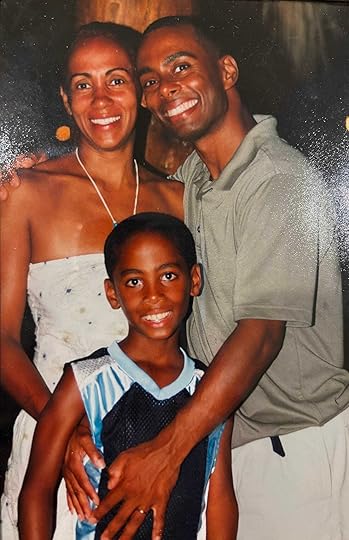

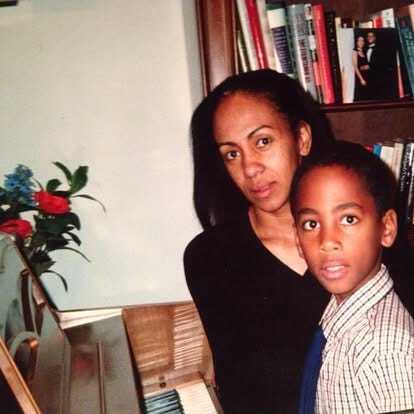

I was 11 or 12 years old when my father called me into the kitchen to break the news. My mother was by his side weeping. “I feel like my body has betrayed me,” she said. She had been diagnosed with breast cancer.

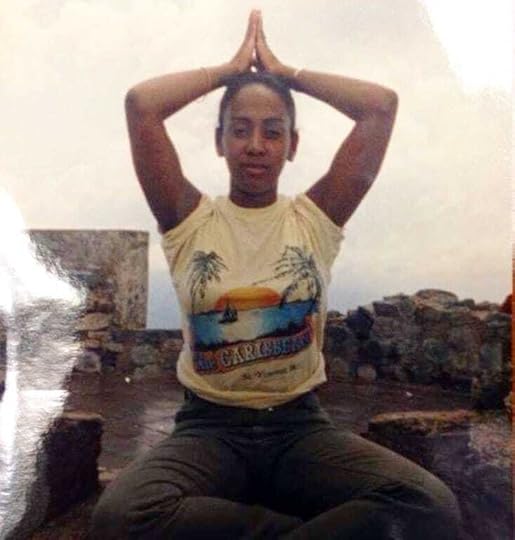

My mother was the healthiest person I have ever met. I never saw her have a drink, except perhaps on New Year’s Eve, and then only half a glass of champagne. She preferred to drink pure vegetable juice daily—a brutal, homemade concoction that she refused to cut with anything sweet. A talented yogi, she had an endearing habit of breaking into headstands almost at random. At 50 years old, she looked 35 at most.

Coleman’s Corner is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

But not even the world’s healthiest lifestyle could protect against a disease that strikes 1 in 8 women, sometimes as a result of genetic predisposition. Whatever the underlying cause of its onset, her tumor was swiftly extinguished through the miracles of modern medicine, which have cut the breast cancer mortality rate by 58 percent from 1975 to 2019. By the time I entered high school, she seemed healthy again—back to daily vegetable juice, yoga, and working on her PhD dissertation. Her skin was glowing. All was right in the world again.

Until one day she disappeared.

It was not unusual for my mother, who was then 53, to go on a retreat for a few days, often to pursue her dissertation research on Ayurvedic medicine in the United States. So when she left our home in Montclair, New Jersey, I barely registered her departure, and certainly did not connect it to her recent complaints about hip pain, which seemed normal enough for a middle-aged adult. But when a few days became a few weeks, and a few weeks stretched to well over a month, I began to wonder just how long a “retreat” could last.

My suspicions were soon put to rest. It was winter of my junior year (I remember because it was the same day that my then-girlfriend, bucking gender norms, asked me to prom) when my father, no longer able to keep up the facade, told me that her cancer had returned and spread to her bones. Her “retreat” was, in fact, a medical facility in Arizona where she was receiving chemotherapy.

Seeing my mother at the airport, after months apart, was the first of two major turning points for me. Up until then, I had only experienced sadness and anxiety about her illness. I had not yet experienced shock and horror. In a few short months, as I had grown stronger and taller, she had not only become thinner but several inches shorter. Only her face was recognizable. Her hips were visibly asymmetric, turning what was once an elegant stride into an awkward gait.

The next two years of my family’s life would be defined by my mother’s attempt to battle against stage 4 bone cancer. There is a grim cliché in the cancer world: The thing about stage 4 is that there is no stage 5. I probably hadn’t heard it at the time, but it wouldn’t have mattered if I had. I simply did not, could not, consider the possibility that my mother might die.

Throughout my senior year, her body deteriorated. When I came home from school, I would notice her awkward gait worsening, her grimaces intensifying. Before long, she could walk only short distances. It is hard to say what was worse—the pain inflicted directly on her by the tumors expanding inside her bones, or indirectly by the side effects of attacking them with bags of poison.

But even when the cancer spread from her skeleton to her liver, death was nowhere on my mental horizon. Years later, I would discover one of my diary entries from the time, in which I had written, earnestly, “I think my mom will live to be 100.”

“When I came home from school, I would notice her awkward gait worsening, her grimaces intensifying. Before long, she could walk only short distances.”

“When I came home from school, I would notice her awkward gait worsening, her grimaces intensifying. Before long, she could walk only short distances.”The moment that pierced my delusional optimism—the second major turning point—was when my father sat me and my older sister down and said, “Your mother’s life is no longer measured in years, but in months.” The five-year survival rate for metastatic liver cancer alone is 4 percent. They don’t even bother to list numbers for patients in my mother’s situation: cancer that migrates from the breast to the bone and the liver. At that moment, however, it was not any statistic that convinced me; it was the look on my father’s face. I accepted, for the first time, that it was not a matter of if she was going to die, but when. And, crucially, how.

My mother spent her last two months at one of the top hospitals in the country, first in palliative care, and eventually in hospice. Most of the time she was in pain. There was morphine on tap, along with every other pain-management drug that Western medicine can legally provide. And yet the pain defeated every attempt to tame it. Eventually she could not bear it.

I cannot pretend to know what it feels like to have tumors expanding inside your skeleton, pressing on your nerves and spinal cord—to have one’s body rearranged from the inside. Nor can I imagine how the realization that the pain has no higher purpose—that you’re no longer fighting any battle, just waiting to die—might destroy whatever resilience had previously been sustaining you. What I can say is that, from the outside, it looked indistinguishable from being tortured.

The only saving grace in my mother’s case was that she died somewhat sooner, and less painfully, than she otherwise would have—and on her schedule, surrounded by her family. That is because the doctors at the hospital helped her die, though it was illegal for them to do so. (For that reason, I am not saying where she got her final treatment.)

This was not a decision she came to lightly or quickly. She faced two choices: (1) to die painlessly on a day of her choosing, surrounded by her family, or (2) to experience extreme and escalating pain for the next few weeks, and then die at a random time, possibly alone. She chose the former, as would I if I were in the same situation, and the doctors helped her do it via a high dose of morphine. As a result, we all got to say our last words to her, and we were all in the room with her the moment she passed.

My mother experienced the early stages of what polite society calls a “bad death.” It is a term that I cannot use except in scare quotes—the same way one might call Adolf Hitler a “bad guy.” It manages to be accurate while entirely missing, and indeed minimizing, the gravity of the subject. If you haven’t seen a “bad death,” then you’re lucky. If you have seen one, then you are never going to unsee it.

I have told my mother’s story not because I think it is remarkable or unique, but because I think it is more common than you’d imagine. It is impossible to say how many illegal assisted deaths occur. Any doctor who admitted to performing one would in theory risk prosecution, as in the high-profile case of Dr. Jack Kevorkian, an American doctor and euthanasia advocate who helped over 100 patients die in the 1990s. Nicknamed “Dr. Death,” he was tried a total of five times, with the final trial ending in a conviction for second-degree murder. For others, it is not prosecution but internal investigations they must fear. In one survey, 4 percent of American palliative care doctors said they had been formally investigated for hastening the death of a patient. Such investigations are a risk taken by doctors like my mother’s who help their terminally ill patients die.

Its illegality comes with other downsides. Besides the fact that some doctors may not be willing to provide a medically assisted death at all, the doctors who are willing to perform it (usually for reasons of personal conscience) must face the other elements in the hospital whose interest is in protecting the hospital from liability. In our case, a young woman we had never seen before barged into the room just hours before my mother died and explained in loud legalese that the hospital did not sanction euthanasia and was absolutely not going to help her die. She disappeared as quickly as she came. I’ve never forgotten how disrespectful, indeed jarring, her contribution was.

One of the few cultural venues I have seen grapple with euthanasia was the hit show House, M.D., which aired on Fox from 2004 to 2012. In an episode called “Known Unknowns,” Dr. Wilson, the hospital’s top oncologist, decides to give a speech at a medical conference breaking the silence about the practice. Ultimately, to protect his friend from legal trouble, Dr. House gives the speech in his stead. The opening line is “Euthanasia: Let’s tell the truth. We all do it.” The crowd of oncologists reacts with shock, not because they disagree, but because they’d never seen anyone say it openly. A fellow oncologist comes up to him and thanks him for his bravery.

One can easily dismiss a fictional television show, but fiction may be the safest venue in which to discuss a practice that is illegal, but in many cases, morally required—or so I would argue. As to its scope, all I can say is that the doctors who helped my mother die did not give me the impression that it was their first time. Given that it remains illegal in 39 U.S. states, it is not hard for me to imagine that it happens every day.

“Years later, I would discover one of my diary entries from the time, in which I had written, earnestly, ‘I think my mom will live to be 100.’ ”

“Years later, I would discover one of my diary entries from the time, in which I had written, earnestly, ‘I think my mom will live to be 100.’ ”People have a false reverence for letting “nature take its course,” as if there is something romantic about even the most brutal ways in which Mother Nature can author our final moments. (Though for whatever reason, far fewer are seduced by this falsehood when it comes to their terminally ill and suffering pets.) While there may be some silver linings to losing a parent—one grows and matures; one internalizes the Hallmark card cliché that life is short and precious—I can say from experience that there is no silver lining to watching a loved one die in excruciating agony. It is a trauma without a lesson.

If there is one I can strain to generate, it’s the fact that the experience will inoculate you against some of the spurious arguments against “assisted dying” laws, such as the one being debated in the UK Parliament right now. If the bill becomes law, then terminally ill people with a prognosis of six months or less—people in my mother’s category—would, at their own request, be able to self-administer a fatal cocktail pending the approval of two doctors and a High Court judge.

The majority of the British public supports the idea. In America, Pew has found public opinion to be split right down the middle, whereas Gallup has found that a majority have supported the policy from the 1990s through to the present. But the opposition, on both sides of the Atlantic, remains fierce—motivated by false concerns about a “slippery slope” and, to be frank, ignorance.

The kind of ignorance one sometimes hears in this debate is that we don’t need assisted dying, we just need better palliative care. This view holds that Western medicine has more or less solved the problem of severe pain. Cases like my mother’s, in which even our best palliative care could not stamp out such pain, are thought to be vanishingly rare—lightning strikes not worth building policy around.

But my mother’s case is instructive. She contracted the most common type of cancer a woman can get, which metastasized in one of the most common ways, and got the best hospice care available to upper-middle-class Americans. Yet she still experienced unbearable pain in her final chapter. Nor is this merely anecdotal. A recent study of over 300,000 terminally ill patients in Sweden, a country not exactly known for its bad medical care, found that 35 percent of those who died from cancer experienced “severe forms of pain” in their last week.

The most substantive argument trotted out against assisted dying is that it would lead to a slippery slope: First it’s terminally ill adults, then it’s almost terminally ill adults, then it’s the disabled, and before long, it’s depressed teenage girls. Once we admit the principle that suffering is a valid reason to end your life, the thinking goes, we will have no arguments to fend off the activists who will expand the categorization.

But the notion that we’ll inevitably slide from cases like my mother’s to allowing anxious teenagers to off themselves is far-fetched, not only because the two categories are easy to distinguish, but also because the experiment has been run, and it hasn’t happened. Oregon has allowed assisted dying—strictly for the terminally ill with six months to live—longer than any other jurisdiction on Earth. And since the law was passed in 1997, it has never expanded an inch outside of those boundaries. The same is true in other places where it has since been legalized, like Australia and New Zealand.

Critics point to the examples of Canada, the Netherlands, and Belgium, where horror stories do exist. In the Netherlands, for instance, a 29-year-old autistic woman with depression successfully applied to commit suicide earlier this year. Belgium, meanwhile, saw a case in which a man with dementia was killed not at his own request, but at his family’s. In Canada, a man was granted the right to an assisted suicide because of “hearing loss.” I agree with the critics who view these cases as profoundly disturbing.

However, the horror stories from these countries actually cut against the “slippery slope” argument, because none of these countries ever had a policy that was restricted to the terminally ill to begin with. Canada’s bill C-14, the law that first legalized assisted suicide, was open to anyone for whom death is a “reasonably foreseeable” consequence of an “incurable illness”—which could mean almost anything. In the Netherlands’ first assisted dying law, patients needed only to have an “incurable illness” (not a terminal one) and experience “unbearable suffering,” which is highly subjective. And in Belgium, too, assisted dying was open to patients who were not terminally ill right from the start.

Assisted dying, writes Hughes, represents an opportunity to prevent an immense amount of needless suffering in the world.

Assisted dying, writes Hughes, represents an opportunity to prevent an immense amount of needless suffering in the world.Instead of a slippery slope, what has emerged over the past three decades are two distinct policies: one restricted to people on their deathbed and exemplified by Oregon, Australia, and New Zealand; and the other open to anyone who is “suffering” and exemplified by the Benelux nations and Canada, without any slippage between the two. It is not a coincidence that all the horror stories come from the latter. The lesson for the rest of the world is not to throw out assisted dying altogether, but to copy the policy that works, and avoid the policy that doesn’t.

Aside from the major objections, critics have leveled many practical objections: Do doctors always know when someone has six months to live? Are fatal drugs always painless? What if relatives pressure someone to commit suicide? I may go through these one by one some other time, but here I will simply say this: Once you understand how much suffering is on the other side of this moral equation—that is, once you understand just how bad “bad deaths” are—then you must view these practical objections as problems to be addressed, rather than as reasons to jettison the whole policy.

It is commonly said that a huge percentage of our healthcare spending comes in the last year of life. But the far more important corollary is rarely said: In many cases, a huge portion—perhaps a majority—of our lifetime suffering comes not just in the last year, but in the last few months. Assisted dying therefore represents an opportunity to prevent an immense amount of needless suffering in the world. If my mother’s story can help even one person come around to this view, then I can say that she did not suffer completely in vain.

Coleman’s Corner is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

November 1, 2024

How the Democrats Rigged the Vote in Puerto Rico

On Tuesday, November 5, Americans will go to the polls and choose their next president. We can only hope there will be no allegations of vote-rigging.

There is, however, one group of U.S. citizens who already knows their vote will be rigged. I’m referring to the 3.2 million residents of Puerto Rico. (My maternal grandparents migrated from Puerto Rico in the 1950s.) Because Puerto Rico is a “commonwealth” of the United States, rather than a state, Puerto Ricans cannot vote in federal elections. But they do get to vote in local elections, which this year includes a nonbinding referendum on the island’s political status—the seventh such referendum in its history.

Coleman’s Corner is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

When they walk into the polling booth on Election Day, Puerto Ricans will be offered three possibilities: (1) statehood, (2) complete independence from the U.S., and (3) sovereignty that includes an ongoing association with the United States. What they will not see is the option of maintaining the status quo.

In previous referendums, the status quo—remaining a commonwealth—has been among the most popular options. So why would the latest referendum suddenly exclude this option? Because the Democratic Party, in concert with Puerto Rico’s pro-statehood party, have designed it that way. There is no other way to describe it: They have rigged the vote to give the statehood option a decisive advantage—and they have done it in plain sight.

The status of the island has long been the most important issue in Puerto Rican politics. It is the main divide between the two largest parties, the Popular Democratic Party (PPD), which advocates maintaining the status quo, and the New Progressive Party (PNP), which would like Puerto Rico to become the 51st state.

It’s no secret that the Democrats would love to see Puerto Rico achieve statehood. They believe it would add another blue state to the union, secure two more Democratic votes in the Senate, and tip the balance of power in their favor. Republicans see statehood as a threat for these same reasons.

Realistically, Puerto Rican statehood could happen only if Democrats controlled both chambers of Congress and the White House, while also eliminating the filibuster—a situation that is unlikely but far from impossible. Should that circumstance ever arise, Democrats have been preparing the ground for Puerto Rican statehood by encouraging referendums on the island. In principle, there is nothing wrong with this. In fact, it’s a good thing to check in on the popular will of Puerto Ricans. To that end, in both 1997 and 2010, House Democrats passed bills calling for straightforward referendums that included the full suite of options.

This time, however, Democrats are playing dirty. In 2022, House Democrats, in consultation with the PNP, passed the Puerto Rico Status Act, which called for another referendum—one that excluded the status quo option. The bill was reintroduced in 2023, this time with more co-sponsors, including Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the most famous American politician of Puerto Rican descent. The Democrats’ bill was then adopted by Pedro Pierluisi, Puerto Rico’s pro-statehood governor, as the basis for November’s referendum.

Removing the status quo option effectively guarantees that statehood will win. This is because in previous referendums, the only options that have received more than 40 percent of the vote were statehood and commonwealth. The other options are essentially nonstarters. Independence, for instance, has never won more than 5.5 percent of the vote, because Puerto Ricans cherish their U.S. citizenship.

And the so-called “sovereignty with free association” formula—whereby Puerto Rico would somehow be both an independent country and retain ironclad U.S. citizenship—has been declared unconstitutional by the Department of Justice multiple times. It is often characterized as a “fantasy.”

A big victory for statehood would constitute an obvious sham to anyone in the know, including Puerto Ricans themselves. The pro–status quo PPD has called the referendum an “anti-democratic mockery,” while the leader of the smaller Puerto Rican Independence Party (PIP) has called it a “plebiscite of lies.” Both parties have instructed their members—collectively constituting some 40 percent of the population—to leave the ballot blank in protest.

Given that most Americans know almost nothing about Puerto Rico, the Democrats are poised to get away with their vote-rigging scheme. The Dems will get what they want—an apparent mandate for eventual Puerto Rican statehood—and most Americans won’t know that this was achieved by cheating.

Democrats have justified this farce by arguing that Puerto Ricans should be presented only with “non-colonial” options—never mind the fact that the commonwealth option has won several referendums in the past. Yet the irony is that the Democrats, while draping themselves in the rhetoric of decolonization, are behaving rather like colonizers. What else can you call an underhanded attempt to force a territory into the union against the will of its residents?

And that’s not the only irony here. For four years, Democrats have rightly complained about Donald Trump’s shameful attempt to steal the 2020 election. In doing so, they have projected an image of themselves as a virtuous party that cares about democracy. Yet here we are, four years later, watching these very same Democrats brazenly rig a referendum in Puerto Rico for the most self-interested of reasons.

The question of Puerto Rican statehood is a complex one with strong arguments on both sides. But we should all be able to agree on this: Whatever happens with Puerto Rico must happen with the consent of its people, as the result of a fair referendum with all options included. Anything less would be a grave disservice to the people of Puerto Rico and a stain on the American project.

Coleman’s Corner is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

October 12, 2024

The Fantasy World of Ta-Nehisi Coates

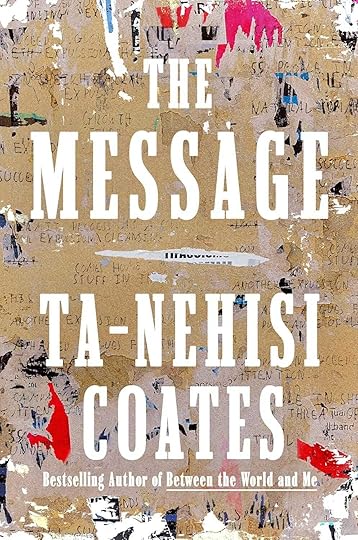

Ta-Nehisi Coates is one of those journalists treated by the left-of-center establishment more like a prophet than a writer. There are few accolades he hasn’t been granted, few prizes he’s yet to win. He’s received a “Genius Grant” from the MacArthur Foundation and a National Magazine Award. Oprah is his producer. And when Coates publishes a book, it’s an event.

His second book, Between the World and Me, won the 2015 National Book Award and spent over one-hundred weeks on the New York Times best-seller list. His 2014 Atlantic essay, “The Case for Reparations,” became so influential that it almost single-handedly made reparations for slavery an issue in the 2020 election. (In 2019, Coates and I both testified before Congress regarding the same issue.)

Coleman’s Corner is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Since then, Coates has focused mainly on fiction and comic books, most notably Black Panther—an inspiring fantasy about an ancient African kingdom guarded by brilliant high-tech warriors rooted in tradition and ringed by envious enemies trying to destroy it. He conspicuously sat out the frenzied period of identity politics that followed George Floyd’s death.

That silence has now broken—though this is hardly something to celebrate. His new essay collection, The Message, is a masterpiece of warped arguments and moral confusion. But it is important to take it seriously, not because Coates’s arguments are serious, but because so many treat them as if they are.

Coates’s overarching themes are familiar: the plundering of black wealth by the Western world, the hypocrisy at the heart of America’s founding ideals, and the permanence of white supremacy. If The Message departs from his earlier work in any way, it’s that his desire to smear America has been eclipsed by his desire to smear Israel—an exercise that takes up fully half the book. (More about that, which Coates has declared “his obsession,” in a bit.)

Things go awry from the start. I hoped it was a heavy-handed attempt at irony when, having just used a George Orwell epigraph to kick things off, Coates subsequently addresses his first essay to “Comrades,” a word that Orwell ridiculed by making it the verbal tic of every totalitarian thug in his novels. But Coates is not being ironic—at least, not intentionally.

In his first essay, “Journalism Is Not a Luxury,” Coates recalls the sentiment that drew him to the written word: the feeling of being haunted. He returns to the word haunted over and over. As a young man he was haunted “by language,” he became obsessed with “what haunted [him] and why,” and ultimately wanted to “go from the haunted to the ghost, from reader to writer.”

I acknowledge the value of being “haunted.” In fact, I quite like the feeling. But my view is that if you want to feel haunted, go listen to Debussy, Radiohead, or Kid Cudi. That way, you will get all of the “haunted” feeling without any of the pretense that you’re learning something of value about the world.

Not everyone would agree that a good journalist needs to be a ghost, or that haunting, rather than informing, is journalism’s primary objective. A contrary view would hold that while a good nonfiction writer can certainly enchant the reader, communicating what is true and useful is a primary part of the job. Put simply, you must give your reader a clear and honest sense of the big picture.

“Coates is not a journalist so much as a composer—one who uses words not to convey the truth, but to create a mood, the same way that a film scorer uses notes,” writes Hughes. (Penguin Random House)

“Coates is not a journalist so much as a composer—one who uses words not to convey the truth, but to create a mood, the same way that a film scorer uses notes,” writes Hughes. (Penguin Random House)Here’s the crucial test of that metric: If you read nothing about a subject other than this author’s work, how informed would you be? To what degree would you understand the big picture?

On that metric, Coates fails spectacularly. Because Coates is not a journalist so much as a composer—one who uses words not to convey the truth, much less to point a constructive path forward, but to create a mood, the same way that a film scorer uses notes. And the specter haunting this book, and indeed all of his work, is the crudest version of identity politics in which everything—wealth disparity, American history, our education system, and the long-standing conflict between Israel and its Arab neighbors—are reduced to a childlike story in which the “victims” can do no wrong (and have no agency) and the “villains” can do no right (and are all-powerful).

Take, for instance, his second essay, “On Pharaohs.” Beginning as an account of his trip to Senegal, the essay becomes a meditation on the relationship between Africans and African Americans—as well as the relationship of both groups to their ongoing “oppressor”: the West.

The essay relies, for emotional weight, on Coates’s assumption that Western nations are rich, and African nations are poor, because of colonialism. This framework makes the West morally responsible for the poverty of countries like Senegal.

But economists have long exposed the problems with this theory. For starters, five-hundred years ago, the whole world was poor. Wealth was created only when certain nations began to adopt a set of key institutions: property rights, honest government, markets, rule of law, and political stability. These institutions rewarded productivity and, in particular, innovation. Every nation that has adopted these institutions has grown exponentially as a result. Every nation that hasn’t has remained in the default state of poverty.

One of the virtues of this theory is that, unlike Coates’s theory, it actually explains the world around us.

Why did Japan and South Korea have similar “growth miracles” in the twentieth century even though Japan was the historic colonizer and Korea its colony? Because they both adopted the key institutions. Why is Ethiopia poor even though it was never a colony? Because, like its African neighbors, it has not yet adopted them.

Insofar as African nations would like to have “growth miracles” of their own, they will need to import the political institutions that reliably create wealth. Most of those institutions are “Western” in origin. Thus, it does no one any good to nurse in Africans a hatred of the West and its institutions—except perhaps Western liberals, many of whom derive a perverse pleasure from castigating themselves, their countries, and their ancestors.

What’s more, colonialism and slavery were hardly Western inventions. As I read this chapter I couldn’t help but remember a detail from Between the World and Me, in which Coates tells his son that he’s named for Samori Touré, who stood up to the French in West Africa. He omits the earlier chapter in Touré’s career when he captured, enslaved, and sold thousands of Africans to Arab, African, and European traders as part of the spoils of his decades-long expansionist empire. This behavior, of course, was considered normal at the time. Which is exactly the point. But reading Coates, you would have no idea that anyone other than Europeans had ever committed such ugly acts.

Mythmaking, rather than history, dominates the book’s third essay, “Bearing the Flaming Cross,” where we learn that Coates had an intimate view of The 1619 Project as it was being created by Nikole Hannah-Jones. The 1619 Project was a series of essays and other works released by The New York Times that sought to retell the American story with slavery and white supremacy as the main protagonists—and to replace 1776 as America’s origin with the year 1619, when the first Africans were brought to Virginia as indentured servants.

As Coates tells it, the backlash to The 1619 Project practically fell out of the sky—or more precisely, resulted from a characteristically American unwillingness to face our past.

“Nikole is my homegirl,” Coates writes. And he “had the great fortune of watching her build ‘The 1619 Project,’ of being on the receiving end of texts with highlighted pages from history books,” and more. “Seeing the seriousness of effort, her passion for it, the platform she commanded, and the response it garnered,” Coates realized that “a backlash was certain to come.”

But the backlash had nothing to do with her passion. It was ignited most of all by Hannah-Jones’ absurd claim that “one of the primary reasons the colonists decided to declare their independence from Britain was because they wanted to protect the institution of slavery.”

This was fact-free revisionism of the lowest order, and it received an onslaught of deserved criticism from the general public and from historians—including Leslie Harris, who had been hired by The 1619 Project for quality control purposes and was left in “stunned silence” when they ignored her fact-checks. None of this appears in Coates’s book.

The trend of deliberate omissions continues when he conveys horror at the fact that “the 2020 protests” were “dubbed by some on the right as the ‘1619 Riots,’ thus explicitly, if in bad faith, connecting the writing and the street.”

The only bad faith here is that which Coates is displaying. I can think of many reasons why a sensible person might see the 2020 riots and The 1619 Project as thematically connected. Here’s one: When the New York Post ran an op-ed entitled “Call Them the 1619 Riots,” his homegirl Hannah-Jones responded by tweeting: “It would be an honor. Thank you.” This, as restaurants, police stations, and shops were being burned and looted all over the country.

Which brings us to Coates’s treatment of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

His final essay is called “The Gigantic Dream,” a reference to one of Theodor Herzl’s diary entries, in which the founder of modern political Zionism explains how he came to the conclusion that the Jews needed a state. Coates begins by describing his visit to Yad Vashem, the magnificent and horrifying Holocaust museum in Jerusalem.

It quickly becomes clear, however, that acknowledging the Holocaust is but a throat-clearing exercise before the main event: over one-hundred pages of the most shamelessly one-sided summary of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict I have ever read.

To tell that story—and it is very much a story, not a history—Coates takes us back.

Not to the establishment of the Jewish state, the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, or the First Zionist Congress but to his childhood in Baltimore. He recalls that he had “a vague notion of Israel as a country that was doing something deeply unfair to the Palestinian people, though I was not clear on exactly what.” He remembers “watching World News Tonight with [his] father, and deriving from him a dull sense that the Israelis were ‘white’ and the Palestinians were ‘Black,’ which is to say that the former were the oppressors and the latter the oppressed.” He recalls his father giving him a book called Born Palestinian, Born Black and appreciating that title.

In other words, Coates inherited an anti-Israel bias—based on crude, inaccurate analogies to American racial politics—on father’s knee. (His father ran an unsuccessful publishing house called Black Classic Press, which “took food off our table,” as Coates writes in The Beautiful Struggle, but was “another tool Dad enlisted to make us into the living manifestations of all that he believed and get us through.” Coates’s father recently republished The Jewish Onslaught, an antisemitic screed about Jews and the transatlantic slave trade.)

The younger Coates carried that homegrown bias through to adulthood, including well into his journalism career. You might expect a writer who routinely attacks white people who never question their childhood biases on race to wrestle, if only for a moment, with the possibility that his own inherited understanding might be clouding his judgment. But that moment never comes.

Many moments never come.

“I was waiting for Coates to mention a single instance of Palestinian terror, but the moment never came,” writes Hughes. The Israeli West Bank Separation Barrier is pictured. (Jakub Porzycki via NurPhoto)

“I was waiting for Coates to mention a single instance of Palestinian terror, but the moment never came,” writes Hughes. The Israeli West Bank Separation Barrier is pictured. (Jakub Porzycki via NurPhoto)For example, I was waiting for Coates to mention a single instance of Palestinian terror, but the moment never came. He does, however, find the space to mention so many of the Israeli policies that were implemented specifically to prevent the terror attacks that murdered so many innocents during the Intifadas—checkpoints in the West Bank, for instance.

Though Coates didn’t look into Israel-Palestine until his 40s, according to his recent New York profile that may be his “greatest asset”—a pair of fresh eyes, as it were. But far from an asset, Coates’s hasty research is a liability, resulting in errors that always come at the expense of Israel. For instance, as an example of Israel’s Jim Crow–like “two-tier society,” he asserts that “Jewish Israelis who marry Jews from abroad needn’t worry about their spouses’ citizenship,” whereas the state “tracks Palestinian noncitizens through a population registry” and “bars Palestinian citizens from passing on their status to anyone on that registry—abroad or in the West Bank.”

The implication conveyed by this sentence—that Israeli law treats Arab Israelis differently than Jewish Israelis—is simply not true. The law in question is neutral as regards the race of the citizen attempting to naturalize his or her foreign spouse. The restriction is instead based on the nationality of the spouse.

Passed during the Second Intifada, the Citizenship and Entry into Israel Law erected barriers to one’s spouse obtaining Israeli citizenship if that spouse was from the West Bank or Gaza. This becomes understandable once you consider that the law was passed in 2003, after a Hamas member who had received an Israeli identity card by marriage blew himself up in a restaurant, killing 16 Israelis. Nor was this an isolated example. Since 2001, 155 Palestinians brought into Israel in this way (before the 2003 ban took effect) have been involved in terror attacks.

In The Message, Israeli policies are (inaccurately) parsed over, while the fact that Mahmoud Abbas still pays the families of suicide bombers who kill Jewish civilians through his so-called “Martyrs Fund” is not mentioned. Nor is the Hamas Charter, which calls for genocide against the Jewish people: “The Day of Judgement will not come about until Muslims fight the Jews. When the Jew will hide behind stones and trees, the stones and trees will say, ‘O Muslims, there is a Jew behind me, come and kill him.’ ” Why discuss the mainstream policies and mission statements of the most important Palestinian organizations when you can caricature Israeli policy and cherry-pick quotes from early Zionists?

Coates finds space to discuss so many things that are tangential to the core conflict: the sales of weapons from Israel to South Africa in the 1970s, for instance, gets several pages. But the Second Intifada, perhaps the foundational episode of modern Israeli politics, in which over 1,000 Israeli civilians were killed in buses, restaurants, and cafés, is referenced only in a passing sentence and without any mention of the Israeli deaths. The fact that this aggression was launched not in reaction to Israel intransigence on the two-state solution but because Israel had offered a historic two-state solution, which Yasser Arafat rejected, is also entirely ignored.

If you’re American, consider for a moment how we all react to mass shootings like the ones in Sandy Hook or Las Vegas: the fear it calls forth for our own lives and especially the lives of our children, the anger it provokes at our impotent politicians, and so on. Now imagine you live in a tiny country the size of my home state, New Jersey, and your tiny country is experiencing a Sandy Hook event every week. Only once you have made that imaginative leap, with full sincerity, can you begin to pass judgment on Israeli policies.

When I issued the litmus test before—if you read Coates and nothing else, would you understand the big picture?—it was not just a hypothetical. Coates is the equivalent of a blockbuster film. Just like some portion of the moviegoing public sees only the occasional blockbuster, some portion of the reading public reads only when it’s someone like Coates. For those people, what he writes in this book is all they will read on the subject of Israel.

If you were one such casual reader, here’s what you would learn: Some 700,000 Palestinians fled or were driven out of their homes in Israel’s 1948 independence war. You would have no idea who started this war or what the Arab side wanted out of it. But you would learn that the Israelis allegedly wanted to restore their “national honor” after being humiliated by the Holocaust, so they figured “routing the savage ‘Arab’ ” would be a good way to do that. You would learn about only two massacres, both of Palestinians: at Lydda and Deir Yassin (though whether these were “massacres” or “battles” remain subjects of ongoing dispute among historians). Naturally, you would come away assuming that the massacres went in one direction only: from Jews to Arabs.

But you’d be missing the most important elements of the original conflict.

You would know nothing about the Hebron massacre of 1929, nearly two decades before the state of Israel existed, in which about seventy Jews were slaughtered by their Arab neighbors. You would have no idea that the United Nations voted to partition mandatory Palestine into a Jewish and an Arab state in 1947—with the Arab state getting 42 percent of the land. You would have no idea that the Jews accepted this proposal, but the Palestinians rejected it (along with the whole idea of partition) and launched the first strike in what became Israel’s war of independence. You’d have no idea that five Arab armies then attacked Israel with the goal of annihilation, and that Israel won this defensive war at the steep price of 1 percent of its total population. And you’d have no idea that the Jewish civilians suffered many massacres in this war, too: at Kfar Etzion and Haifa Oil Refinery, to name two. Coates discusses 1948 at length, but none of these not-so-minor details are mentioned.

It’s hard to overstate how unfair these omissions are. The 1948 war was fought not for honor, but for survival. To suggest that it was fought for honor is to imply that Israelis had a choice whether to fight it. The truth is, had they laid down their arms, they had every reason to expect another genocide. On the other hand, had the Palestinians chosen peace, they might now be celebrating the 76th anniversary of a Palestinian state.

In the West Bank, people walk through the damaged streets of Jenin after a raid by the Israel Defense Forces. “If Israelis put down their weapons, there would be a real genocide perpetrated by Hamas, Hezbollah, and Iran, a country that has vowed to destroy Israel for decades,” writes Hughes. (Spencer Platt via Getty Images)

In the West Bank, people walk through the damaged streets of Jenin after a raid by the Israel Defense Forces. “If Israelis put down their weapons, there would be a real genocide perpetrated by Hamas, Hezbollah, and Iran, a country that has vowed to destroy Israel for decades,” writes Hughes. (Spencer Platt via Getty Images)Much has changed in the conflict since 1948, most of all Israel’s power relative to her enemies. But the fundamental asymmetry of intentions has remained the same.

If Israel intended to commit genocide against the Palestinians, they could have done so decades ago. Instead, the opposite trend has occurred: The Palestinian population has multiplied many times over. If Israel, with all of its power, had genocidal intent, why would they allow such a population boom to occur? Meanwhile, if Israelis put down their weapons, there would be a real genocide perpetrated by Hamas, Hezbollah, and Iran, a country that has vowed to destroy Israel for decades. One wonders if Coates is curious why, for example, the Houthis of Yemen—a country that ethnically-cleansed its Jewish community, which predated Christianity or Islam, after the creation of the Jewish state—has as its motto: “Allah is the Greatest, Death to America, Death to Israel, A Curse Upon the Jews, Victory to Islam.”

You would not know any of this from reading Coates. In fact, he doesn’t even mention the word Hamas—or Fatah, or Palestinian Islamic Jihad, or Hezbollah, or Iran—once. In his telling, the threats don’t exist, only the barriers that Israel erects to contain them.

Coates’s one-sidedness is so egregious that it calls out for a special explanation. Not even Norman Finkelstein (unfair as he is to Israel) omits the phenomenon of Palestinian terrorism altogether. My theory is this: I think Coates, and probably many others, believe that the “other side” of the Israel-Palestine conflict is, simply, the Holocaust. In Coates’s view, you have the Israeli oppression of Palestinians on the one hand and you have the Holocaust on the other, and Coates, in his sage wisdom, is here to tell the world that two wrongs don’t make a right (indeed, in his New York profile he makes that very point).

But the ongoing case for Israeli security measures—checkpoints, for instance—has nothing to do with the Holocaust, and everything to do with preventing terror attacks on Israeli civilians. If America were a tiny country surrounded by annihilationist terror groups attacking us with constant rocket fire (and much worse), we would take hard-line security measures, too. Our citizens would demand it. Being fair to the Israeli side requires grappling with that ongoing reality—something Coates is uninterested in.

While good faith requires giving critics of Israeli policy the benefit of the doubt regarding their motives, certain arguments reveal such a naked double standard that they can only be called antisemitic.

For example, recall that Coates’s second essay is called “On Pharaohs.” You might be wondering what pharaohs have to do with an African American writer’s trip to West Africa—which is where African Americans trace our origins, and is some 2,500 miles away from Egypt. As it turns out, Coates believes that it is not just important but necessary for us to nurse our symbolic connection to ancient Egypt—to indulge our inner Hotep.

After paying lip service to the fact that there’s no science behind it, he ultimately reaches his real conclusion, that “we have a right to imagine ourselves as pharaohs”:

Here is what I think: We have a right to our imagined traditions, to our imagined places, and those traditions and places are most powerful when we confess that they are imagined. . . . And we have a right to imagine ourselves as pharaohs, and then again the responsibility to ask if a pharaoh is even worthy of our needs, our dreams, our imagination.

Though he has endless patience with African Americans’ imaginary connection to a place that our ancestors never lived, he becomes a veritable Richard Dawkins—insistent on strict conformity with the peer-reviewed literature—when the topic is Jewish connection to the land of Israel.

Coates recounts his visit to Jerusalem’s Old City, where he took a tour run by the “City of David” program. “City of David” promises an experience where tourists can walk “in the footsteps of the kings and prophets” in “the place where it all began”—with an emphasis on drawing direct connections, some plausible and others highly speculative, between the Hebrew Bible and modern archaeology.

It should not shock you to learn that there is an element of salesmanship and exaggeration in such a classic “tourist trap” scenario. Still, no serious historian doubts the big picture: Jews had successive kingdoms in the land of Israel, and maintained a continuous presence there even after the Roman Empire destroyed Jerusalem in the first century, and renamed the region Palestine in order to punish the Jews who had rebelled against colonial rule.

Coates, however, is deeply bothered by all of the Jewish storytelling, including the general assertion of a Jewish “title deed” to the land: “What that [Zionist] project needed was an unbroken narrative, stretching back to time immemorial, of Jewish nationhood. With such a narrative in hand, Israel would then have what Ben-Gurion called ‘the sacrosanct title-deed to Palestine.’ As I made my way through the City of David, the evidence of this title deed, much less the presence of the ancient Israelite king himself, seemed extrapolated,” he writes. Coates saw among Israeli Jews a “fragile triumphalism, the desperate need to assert royal lineage and great ancestral deeds.” After extracting from his tour guide an admission that we don’t know whether a real King David existed, one gets the sense that this admission ruined his whole experience. In the end, he writes of his Old City experience: “It all felt so fake.”

In theory, I have no problem with the argument that the City of David tour does not reflect the unbiased consensus of archaeologists. Though at this point it will not surprise you that Coates has not a single bad word to say about the fact that no Palestinian leader has ever acknowledged that there was a Jewish temple in Jerusalem—bucking the scholarly consensus, which says there absolutely was.

What I have a problem with is the glaring double standard: When African Americans claim ancient Egypt (which is like a Korean claiming India), it warms Coates’s heart. But when a Jewish tour guide embellishes about King David, he suffers Coates’s wrath. Some people have a right to our “imagined traditions” and “imagined places,” but Jews dare not dream about their actual ancestral homeland.

The real affront, though, is that Jews did more than dream. They created a modern state that refuses to conform to the fantasy of “white” Jews and “black” Palestinians Coates received as a child.

Coates is free to prefer Pharaoh to Moses, but he writes as if his own personal feelings possess some higher moral authority. He writes, as well, as if he believes that Israel—unlike the 192 other member states of the United Nations—is subject to the authority of his imagination, and might yet be disproved by a stray quotation from David Ben-Gurion, or a grisly wartime fact.

But unlike Wakanda, Black Panther’s imaginary kingdom, Israel is a real and complex place, a living body rather than a ghost, though its existence clearly haunts the author of The Message.

Coleman’s Corner is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

February 1, 2024

Deceitful Affairs

It is for minds like Nathan J. Robinson’s that the phrase “a mile wide and an inch deep” was created.

Robinson, founder of Current Affairs, has written a breathtakingly dishonest review of my new book, The End of Race Politics: Arguments for a Colorblind America. His 4,700-word takedown accuses me of, among other things, “extremely dishonest” manipulation of historical evidence, “intellectual malpractice,” and putting forth a “simplistic, dishonest narrative.”

Coleman’s Corner is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

In reality, his review is guilty of literally every sin it accuses me of. Having acquired a taste for public displays of hypocrisy, Robinson has apparently returned to the buffet line for a second helping. Indeed, I have never read someone so confidently accuse someone of sins that they proceed to commit mere sentences later.

Let’s examine his review claim by claim.

Robinson begins his takedown by treating us to a 700-word extended metaphor about a hypothetical society in which there are two groups: the “A-Group” and the “B-Group”. If you’d like to waste some time, do read the whole thing.

For the rest, here’s the short version: the A-Group and the B-Group are exact stand-ins for whites and non-whites, and the saga they endure mirrors how whites and non-whites have interacted throughout American history. In other words, the A-Group oppresses the B-Group for a long time.

The only difference: what separates these two groups is not color, but some other trait. (Robinson proposes “birthdays," which is an odd choice given that, in his own metaphor, these are supposed to be hereditary groups, and birthdays are decidedly not heritable. A better writer might have chosen, say, hair color. But then, a better writer might have spared us the tedious extended metaphor in the first place.)

Robinson continues: At some point, this system of oppression ends, but the effects linger. Some descendants of the B-Group develop “B-Group pride,” supporting policies that reverse-discriminate in their favor. But other members of the B-Group––people like me, presumably––seek to ditch these arbitrary categories altogether and just stop talking about the whole thing.

At long last, Robinson arrives at the thunderous conclusion––which lands no differently than it would have without the metaphor:

And yet, it will still be the case that the children of the Bs are, on the whole, poorer than the children of the As. And something might strike us as a little strange when we notice the strong statistical correlation between being the child of a former B and being in jail or prison…[ellipsis in original]

In other words, the purpose of this digression––the payoff which justified the whole journey––is the commonplace observation that race, though an arbitrary trait, is nevertheless correlated with all kinds of outcomes. How could it possibly be a coincidence, Robinson asks, that a group that was oppressed for centuries just so happens to be on the wrong end of so many disparities?

This is among the most common arguments made about racial inequality. That’s why I address it in some detail in my book1––arguments that Robinson addresses only in a passing sentence:

Hughes follows Thomas Sowell in appearing to rationalize a lot of disparities, saying that they may result from natural cultural differences or random factors rather than outright discrimination (they might, but the correlation between a centuries-long history of oppression and contemporary wealth disparities is hardly spurious or random).

My short reply is this: Surely, the history of oppression plays a role in the current state of black America. But if one looks at the whole landscape of interracial and intra-racial ethnic disparities (rather than the single data point of African-Americans), there is no way to make sense of the hypothesis that discrimination, past or present, is the main driver of modern-day disparities.

As Robinson didn’t spend much time (or effort) on this point, neither will I. A longer discussion can be found in my book.

Let’s move on to the core of Robinson’s critique.

According to Robinson, I argue that we should stop talking about race. Full stop. Even more extreme, apparently I argue that talking about race makes you a racist. His objection to this pair of arguments is arguably his central critique of me––the thread that runs through his whole essay.

Twice, he quotes the following out-of-context sentence from my book: “Racial talk makes racist thought”2––once in the final sentence of his essay and once here:

“Racial talk makes racist thought,” Hughes says. This makes about as much sense as saying that talking about class makes you a classist, talking about gender makes you a sexist, and talking about nations makes you a nationalist.

Of course, I don’t believe that talking about race makes you a racist. That would be crazy. Robinson is practicing an egregious example of selective quotation.

Here is the paragraph that immediately follows the “Racial talk makes racist thought” quote in my book:

Let me make one thing clear: I’m strongly in favor of talking about real instances of racial discrimination and real systemic discrimination in institutions. To give one example, a sting operation with trained actors and secret cameras discovered that Long Island real estate agents discriminated against 19 percent of Asian prospective homeowners, 39 percent of Hispanics, and 49 percent of blacks. That’s worth talking about. But most mainstream racial talk doesn’t deal with actual racism. (bold mine)3

It’s hard to see how I could possibly have made it more clear that I’m in favor of talking about actual racism––and that the “racial talk” I am opposed to is, by default, something other than discussions of real racism.

Could an honest journalist read that passage and come to the conclusion that:

(1) I believe people should just stop talking about race, with no qualification, or…

(2) I believe talking about race makes you a racist?

I don’t think so.

On to the next strawman:

But while Hughes’s response to the impact of centuries of racism is legitimate, his distortions of the other point of view are not. Hughes accuses contemporary anti-racists of “race supremacy,” saying they agree with white supremacists that “some races are superior to others.” In fact, Kendi says precisely the opposite, writing that “whenever someone says there is something wrong with White people as a group, someone is articulating a racist idea.”

Nowhere in my book do I claim that Ibram X. Kendi endorses race supremacy. In fact, the section Robinson is quoting from––“Race Supremacy Returns”4––does not mention Kendi’s name even once (though I do give several examples of people who aren’t named Kendi promoting anti-white bigotry).

In Robinson’s imagination, apparently a lively place, he’s informing me that Kendi rejects race supremacy––something I clearly must not know.

He is about four years too late. Back in 2019, I wrote the following sentence in my review of Kendi’s book for City Journal: “Having matured out of his anti-white phase, Kendi takes a refreshingly strong stand against anti-white racism in the book,…”

If I were writing as defensively as possible––in anticipation of a Robinsonian level of bad faith––I would have said that many neoracists endorse race supremacy instead of what I actually wrote––which was simply: “They endorse a type of de facto race supremacy.” This, perhaps, would have closed the door to interpreting my statement as applying to every single person whom I elsewhere call a “neoracist”.

But one either writes elegant prose with the proverbial smart-but-uninformed reader in mind, or one writes a mess of annoying caveats with one’s most uncharitable critic in mind. The majority of readers, I assume, will be happy that I did the former.

“Intellectual malpractice,” what Robinson accuses me of, is a rather good term for what he does here:

Hughes is similarly manipulative in his discussion of Bayard Rustin. In a video for the New York Times, Hughes presents Rustin as being “opposed to affirmative action.” One need only open a copy of Rustin’s collected writings to find that, while he opposed a numerical racial quota system, he in fact wrote (on behalf of the A. Philip Randolph Institute) that “the affirmative action concept [is] a valid and essential contribution to an overall program designed to ameliorate the current effects of racial bias,” praising “special efforts to include those groups that had been previously excluded.” Rustin certainly had a strong critique of existing affirmative action programs, and argued strongly that the primary focus should be on creating an economy that guaranteed a decent standard of living for all. But it is unconscionable to leave out the nuance here, which is why leaders of the A. Philip Randolph Institute objected to a prior attempt to oversimplify Rustin’s views. They noted that Rustin chaired a program specifically designed to “rectify underrepresentation of blacks and other minority groups in the construction and building trades.”

Robinson is wrong about this. And the hubris dripping off of a phrase like “One need only open a copy of…” is particularly ironic given that his knowledge of Bayard Rustin’s writings appears to be severely limited.

Rustin did not just oppose quotas. He also opposed (non-quota) preferential treatment in hiring and admissions––what we today call “affirmative action.” To understand this, we must first define terms.

“Affirmative action” has had at least four different definitions:

(1) Nondiscrimination: The original definition, articulated in executive orders by President Kennedy and President Johnson, was simply hiring “without regard to race”––i.e., color-blindness.

(2) Outreach-plus-nondiscrimination: What historian of the policy Melvin Urofsky labels “soft affirmative action”: making extra efforts to reach minority candidates, followed by judging them purely on colorblind merit. Importantly, this is not what we mean by “affirmative action” today.

(3) Preferential treatment––i.e., taking race into account in the decision whether to hire or admit somebody without using quotas. This is what we mean today by “affirmative action”––see, for instance, the recent Supreme Court case.

(4) Racial quotas, which have been banned for some time but were alive when Rustin was writing.

When we talk about “affirmative action” today, we’re talking about #3. And Rustin opposed #3.

Now let’s look at the record, which Robinson either obscures or is unfamiliar with.

Robinson cites two pieces of evidence to back up the claim that I’ve misrepresented Rustin’s views. The first is a quote pulled from Rustin’s 1974 essay, “Affirmative Action in An Economy of Scarcity”:

“The A. Philip Randolph Institute believes the affirmative action concept to be a valid and essential contribution to an overall program designed to ameliorate the current effects of racial bias, and, ultimately, to achieve the long-sought goal of racial equality”.

The crucial question––not even asked by Robinson, much less answered––is which definition of “affirmative action” Rustin was supporting here. In the context of the rest of the essay, it appears he was referring to #2, not #3.

We can infer this because Rustin ends the very same essay with a 4-point plan––curiously omitted by Robinson––for how “affirmative action” should be implemented. In that plan, he literally suggests that hiring procedures should in some cases be left to race-blind lotteries. Point 1 of Rustin’s plan, in its entirety, is:

"Affirmative action efforts should be largely directed to instances of racial discrimination. In place of ratio or quota formulas, those institutions that have been found guilty of practicing discrimination should be given stiff fines; in other instances of recalcitrance, such as have been exhibited by Southern police departments, government should consider asking the courts to institute racially blind lotteries to determine hiring procedures”. (bold mine)

The only other piece of “evidence” Robinson cites is a letter written by Norman Lynch of the A. Philip Randolph Institute…after Bayard Rustin died. Lynch’s letter does not specify which definition of “affirmative action” he has in mind: Preferential treatment, quotas, outreach, non-discrimination? We are left to guess.

More importantly, why cite material not written by Rustin when Rustin left so much writing behind? Is Robinson unaware of Rustin’s other writings on the topic? Or did he intentionally omit them?

Here are two other pieces of evidence––undiscussed by Robinson––supporting the claim that Rustin opposed both quotas (#4) and preferential treatment (#3).

In 1974, Rustin wrote a letter to the editor of the Wall Street Journal, correcting a false assertion that "quotas and preferential treatment" were the brainchildren of the Civil Rights movement (of which Rustin was a lead architect). Instead, Rustin writes that they were the unfortunate consequence of the Nixon administration.

The controversy over quotas and preferential treatment did not originate in the agenda of the civil rights movement, except insofar as that movement provided the impetus for all subsequent efforts to enhance the status of minorities. The leaders of the civil rights movement—King, Randolph, Wilkins, and others—were explicit in opposing reverse discrimination. They were opposed on philosophical grounds, but were also motivated by pragmatic political considerations…Which brings us to a basic point, albeit one which is often overlooked or dismissed as of secondary importance. And that is that quotas are the progeny, not of the program of the civil rights movement, but rather of the economic policies of the Nixon administration and of the shortcomings of the administration’s bureaucracy. (bold mine)5

The penultimate sentence of the same letter is: "Weakening the merit principle and legitimate standards does no benefit to society, least of all to minorities."

In his 1970 essay, “The Failure of Black Separatism,” Rustin celebrated a poll result which reported that blacks overwhelmingly rejected “preferential treatment in hiring or college admission.”

It is insulting to Negroes to offer them reparations for past generations of suffering, as if the balance of an irreparable past could be set straight with a handout. In a recent poll, Newsweek reported that “today’s proud Negroes, by an overwhelming 84 to 10 percent, reject the idea of preferential treatment in hiring or college admissions in reparation for past injustices.” There are few controversial issues that can call forth a greater uniformity of opinion than this in the Negro community.6

In sum, what we today call “affirmative action”––non-quota preferential treatment in hiring or admissions––is a policy that Rustin opposed. What he did support was an older definition of “affirmative action”––outreach-plus-nondiscrimination––that is no longer in use today. It is only through selective and out-of-context quotation (precisely what he accuses me of) that Robinson is able to argue the opposite.

According to Robinson, I deliberately mislead my readers about Thurgood Marshall’s views:

Hughes also cites Thurgood Marshall’s belief in a color-blind Constitution, but doesn’t tell his readers about how Marshall acted after he was appointed to the Supreme Court. The issue of affirmative action came before the court in the famous case of Regents of the University of California v. Bakke (1978), which considered whether racial preferences in state school admissions policies were constitutional. Marshall gave a strong, unequivocal defense of the use of preferences to make up for past discrimination. Let’s see what he had to say:

Then we get a long block quote from the late 70s in which Thurgood Marshall defends race-based Affirmative Action. And Robinson continues: