Pamela D. Toler's Blog

November 26, 2025

Overwhelmed and Very Grateful

I keep looking for another vintage Thanksgiving postcard, but most of them have creepy children wielding axes and heading toward apprehensive turkeys.

As I write this, I am sitting in a hotel in Miami. I spent yesterday at the Miami Book Fair, where I spoke about Sigrid Schultz, signed books, attended a couple of panels, navigated crowds, and listened to some wonderful music. It’s been exciting, humbling, nerve-wracking, and exhausting.[1] In a couple of hours I will catch a plane back to Chicago, where I’ll have two days at home before My Own True Love and I head to the Missouri Ozarks for Thanksgiving with my family.

In some ways, this is emblematic of my last year: lots of travel, lots of chances to talk about The Dragon from Chicago (on line and in real life), lots of stepping outside my comfort zone. Even though I occasionally have to remind myself just how lucky I am, I am grateful for the opportunities. (And the fact that people have showed up at my events. Every author I know lives in fear of the event where no one comes.)

I say it every year, but I am also so very grateful for those of you who read History in the Margins, week after week. You send me comments and suggestions. You ask hard questions. You share my posts with your friends. Without you, I would be talking to myself.

Happy Thanksgiving to you all.Here’s to another year of exploring history together.

[1] I did not go to the parties on Friday and Saturday night, or take advantage of any of the other opportunities to meet and mingle with my fellow authors. Which would have been a good thing, but I just didn’t have the juice. This kind of thing is difficult for those of us who are very introverted and more than a little shy.

_______________________

Speaking of sending me ideas, I am currently issuing invitations to my annual Women’s History Month series of mini-interviews. I have some great people on board already, but I need more. If you “do” women’s history in any format, or know someone who does, or have an idea of someone you would love to see in the series, drop me a line. I’ve interviewed academics, biographers, podcasters, historical novelists, tour guides, poets, and even a textile artist LINK, but would be happy to talk to people who explore women’s history through music, puppet shows, graphic novels, other visual arts, interpretive dance….

November 24, 2025

From the Archives: Marina Warner’s Stranger Magic (aka Fairy Tales, Pt. 3)

While I was checking the archives to be sure that I hadn’t previously written about Antoine Galland’s Thousand and One Nights, I ran across this review from 2012, which led me to pull Stranger Magic off the shelves and dive in.

***

I’m fascinated by the Arabian Nights. By the stories themselves and the way they fit together into their complicated frame story. By their transformation from Arabic street tales to a established position in the Western canon. By their echoes in Western culture, from the Romantic poets to Disney.

So I was delighted to get a chance to review historian and critic Marina Warner’s new work on the tales.

Marina Warner’s Stranger Magic: Charmed States and the Arabian Nights is a multi-faceted study of the popular tales of wonder and magic known as the Arabian Nights.

Warner discusses the tales in the Arabian Nights with the interdisciplinary approach that she used to good effect in her earlier study of Western fairy tales, From the Beast to the Blonde. She examines them through the lenses of literary criticism, history, folklore studies, feminist theory and popular culture. She pays particular attention to the history of the Arabian Nights in the west, from the reception of the first translation from the Arabic by Antoine Galland in the eighteenth century through its influence in works as distinct as Mozart’s operas and the Harry Potter books.

Not assuming that readers will have the same familiarity with “The Prince of the Black Islands” as they do with “Sleeping Beauty”, Warner retells fifteen tales before she unravels them into their constituent themes, symbols and assumptions. She moves easily from the Biblical story of King Solomon to magic carpets, from the reputation of Egypt as the home of ancient magic to Sir Isaac Newton’s alchemical experiments, and from the wealth of the Islamic world in the twelve century to post-Reformation anxiety about Catholic religious practices.

Warner succeeds once again in balancing entertainment with erudition. Like her earlier works, Stranger Magic is accessible enough for the general reader and rich enough to keep a specialist scribbling in the margins.

November 20, 2025

Fairy Tales, Pt 2: Antoine Galland and the Arabian Nights

When I sat down to write about Charles Perrault and Tales of Mother Goose, I had no intention of writing more about the writers who “created” fairy tales as we know them . But as I wrote about Perrault I remembered some of my favorite stories,[1] and stumbled across a new one. Suddenly a small series of blog posts presented themselves.[2]

Next up, Antoine Galland (1646-1715) : classical scholar, linguist, diplomat and the man who made Les Mille et Une Nuits (The Thousand and One Nights), better known in English as The Arabian Nights, a canonical work in Western literature.

Trained as a classical scholar, Galland worked as an interpreter for the French diplomatic mission in Constantinople, from 1670 to 1675, where he studied Turkish, modern Greek, Arabic and Persian. Back in France, he became the curator of the royal collection of coins and medals.[3] He held the chair of Arabic at the Collège Royal in Paris from 1709 until his death in 1715. Over the course of his career, he collected, transcribed, and translated many Turkish, Persian and Arabic manuscripts.

The Thousand and One Nights was a diversion for Galland. He worked on the tales after dinner as a way to unwind after a long day of serious scholarship—I picture candlelight, a glass of wine, and perhaps a large cat purring next to him on the work table.[4] (

Galland drew most of his stories from several Arabic manuscripts of collected tales. The collections were drawn from a a body of oral tradition—popular tales told by street entertainers, based on folklore that stretched from India to Egypt. Each storyteller augmented plots, embroidered descriptions, and filled the tales with literary allusions and quotations to reflect both his own taste and that of his audience. Over time, Arab literati collected the stories, much as Jakob and Wilhelm Grimm collected fairy tales from German peasants in the 19th century, and the tales in the resulting manuscripts varied according to the time and place they were heard and the taste of the man compiling the collection.

In some ways, Galland was not unlike the Arab coffeehouse storytellers who recounted—and often tailored—familiar tales to their audiences. Galland selected the stories he deemed most suitable for a European audience, and in so doing established a canon of tales for Europeans that is distinct from the original material. Aimed at a courtly rather than a scholarly audience, Galland’s translation was often deliberately inaccurate. As he wrote to Cuper, his version was not “attached precisely to the text, for that would not have given pleasure to the readers. To the extent that it was possible, I have rendered the Arabic into good French without being slavishly attached to the Arabic words.”

Galland’s Thousand and One Nights was published in France in 12 small volumes between 1704 and 1717. He deliberately targeted the audience who had enjoyed Perrault’s fanciful tales. If anything, he was even more successful. The ladies of the court were so impatient to know what happened next that Galland had to lend them manuscript versions that they passed from hand to hand until the next volume was published. That’s the kind of audience an author can only dream of.

[1] Including one outlier in the mid-nineteenth century.

[2] And happy I was to see them. I have a long list of possible posts, but none of them were calling my name.

[3] Just to make the timing clear, Galland , like Perrault, worked during the reign of Louis XIV

[4] It’s a seductive image It’s taken me several years to break myself of the habit of going back to work after dinner. I can imagine all too well the lure of working on something that isn’t really my work. Luckily I have My Own True Love to keep me honest. (Ms. Whiskey would be all for going back to the desk.)

November 17, 2025

Charles Perrault: The Father of the Fairy Tale?

I recently had reason to track down a few details about the story of Puss-in-Boots, which I frequently confuse with Dick Whittington and his cat[1]. Along the way I fell down rabbit hole or two about the story’s “author” Charles Perrault (1628-1703). (Does this surprise anyone?)

Charles Perrault (no cat)

Perrault is best known for the collection of fairy tales known as Contes du temps passé (Stories of Times Past), more widely known by its subtitle, Tales of Mother Goose. But Perrault didn’t come to writing fairy tales until late in life.

The youngest of three sons of a wealthy Parisian family,[2] Charles Perrault trained as a lawyer, like his father before him, but he spent most of his life working as a civil servant.. When his brother older Pierre purchased the position of principal tax collector of Paris in 1654,[3] he became his brother’s clerk. In 1663, he became secretary and cultural advisor to Jean-Baptiste Colbert, Louis XIV’s powerful finance minister, a position that held a certain amount of clout. Among other things, Perrault used his position to successfully argue that the Tulieres Gardens should remained open to the public[4], persuade Colbert to establish a pension fund for writers and scholars, and get his other older brother Claude appointed as architect for the Louvre.

That same year, Perrault became Secretary of the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles Letters, a learned society created by Colbert for the purpose of composing Latin inscriptions for public monuments and the medals issued to celebrate events of the king’s reign. During his years in this position, Perrault was involved in the artistic world of the court in a a number of ways. He wrote a book titled La Peinture (Painting) to honor the Louis XIV’s favorite painter, Charles LeBrun and scripts for royal celebrations. He was responsible for the inclusion of thirty-nine fountains, each representing one of Aesop’s fables, in the labyrinth of the gardens of Versailles. And he built a reputation in the court’s literary circles for light verse and love poetry, the type of thing that was recited as part of an evening’s entertainment at society parties.

Perrault was elected to the Académie Française in 1671,[5] where he played a prominent role in the literary controversy known as the Quarrel of the Ancients and Moderns. The “Ancients” argued that the literature of ancient Greece and Rome was the unchanging model for literary excellence. The “Moderns” believed that just as the science of their day had surpassed that of the ancients[6], modern literature, too, had progressed alongside a more civilized society. Perrault was on the side of the moderns. In fact, he set off the argument when he read a long poem at a meeting of the organization, titled The Siècle de Louis le Grand (The Age of Louis the Great), in which he argued that the modern world was superior to the ancient world in every way, thanks to the enlightened rule of the Sun King.

Frontispiece of Tales From Mother Goose, with Mother Goose herself spinning a tale, and some yarn

In 1695, at the age of 67, Perrault lost his secretarial post. (None of the accounts I read said why.) Left with time on his hands, he began to write stories inspired by existing folk tales, including “Little Red Riding Hood,” “The Sleeping Beauty,” “Puss in Boots” and “Bluebeard.” The stories may have been familiar, but the style was his own[7]. They were embellished, modernized versions of traditional stories, set in a fairy tale version of seventeenth century society that would have been familiar to his readers. (In their own way, the tales were another salvo in the Quarrel Between the Ancients and the Moderns.) Published in 1697, Tales from Mother Goose, was aimed at the same audience that enjoyed his light poetry.. It was an instant and enduring success.

Perrault is often credited with creating the genre of the literary fairy tale, but while he is the most well known and arguably the most important of writers in the genre, he wasn’t the first member of the Parisian literary salons to write such tales. Marie-Catherine Le Jumel de Barneville, Baroness d’Aulnoy (1652-1705) not only preceded him, but she coined the term “fairy tale” to describe the genre.[8]

Making Perrault the genre’s favorite uncle, in my opinion.

[1] And why not, since in both stories a poor orphan boy rises to high estate with the help of his cat.

[2] Sounds like a fairy tale right from the start, doesn’t it?

[3] Buying official government positions (and military commissions) was common in the seventeenth century, without reference to the office holders’ qualifications for the post. That said, the Perrault brothers seem to have been talented and hardworking

[4] Louis XIV wanted to make them private.

[5] A different Académie, originally created to maintain standards of literary taste. It has been in existence since 1634, with a brief interruption during the French Revolution. Today its primary role is to regulate the French language.

[6] There is a lot of stuff packed into that premise that I am not going to touch in this post.

[7] Much like Antoine Galland, who, a decade later, took Arabic street tales and transformed them into the canonical work of Western literature known as The Thousand and One Nights, or the Arabian Nights. A story that I realize I’ve never told here on the Margins. Hmmm.

[8] She may need a blog post of her own soon. I make no promises.

November 13, 2025

From the Archives: The Nile

It is inevitable, at some point after I’ve returned from a trip I run out of blog-post steam. The notes I have made for myself about future posts no longer fire my imagination, or I don’t have enough information to turn them into stories.[1]

Before I give up and move on to the other stories that are clamoring for my attention, I’d like to share a review I did in 2014 about the account of another writer’s boat trip through history.

In The Nile: A Journey Downriver Through Egypt’s Past and Present, popular Egyptologist Toby Wilkinson leads the reader on a historical travelogue that moves from Aswan, home of the river’s First Cataract, to Cairo’s Gezira Island, from Paleolithic rock drawings to the Arab Spring.

The voyage that shapes The Nile is not simply metaphorical. Wilkinson floats down the river on a dahabiyah–a large luxury boat descended from the royal barges of the pharaohs. Aware that he is simply the latest in the historical line of travelers drawn to Egypt by its climate and its ancient civilizations, Wilkinson engages with their commentary as well as his own observations, creating a palimpsest of Nile voyages in the process. (Ancient Greek historian Herodotus and 19th-century British journalist Amelia Edwards are particular favorites.)

Because Wilkinson organizes his work by geography rather than chronology, his narrative is anecdotal almost to the point of stream of consciousness. His combination of scholarship and storytelling allows him to draw unexpected relationships through time. The ruins at Kom Ombo lead to a discussion of the crocodile god, Sobek, then on to ancient Egyptian tales about the dangers of crocodiles, a modern Crocodile Museum, and the impact of both 19th-century Western tourism and the Aswan Dam on the crocodile population in Egypt. Occasionally such temporal leaps are disorienting, but for the most part they are illuminating. Once a reader has learned to navigate the rapids, The Nile is worth the effort.

[1] For instance: Egypt used the (unwritten) Nubian language as a military code in its war with Egypt in 1973. Aa fascinating tidbit, but not enough to turn into a post. (And I really tried. Many rabbit holes were explored before I gave up.)

November 10, 2025

From the Archives: Word with a Past–Parchment

And speaking of papyrus, as I believe we were, here’s a story that I first shared in 2013 in which papyrus played a critical role. It’s one I’ve always enjoyed. I hope you do,too.

For hundreds of years papyrus was the principal material on which books (or at least hand-copied scrolls) were written. Since it could only be made from the pith of freshly harvested papyrus reeds, native to the Nile valley, Egypt had a monopoly on the product–and a potential monopoly on the written word.

In the second century BCE, the kingdoms of Egypt and Pergamum* got into an academic arms race.

The library at Alexandria had been an intellectual power house since it was founded by King Ptolemy I Soter in 295 BCE. Ptolemy set out to collect copies of all the books in the inhabited world. He sent agents to search for manuscripts in the great cities of the known world. Foreign ships that sailed into Alexandria were searched for scrolls, which were confiscated and copied.**

Thirty years later, King Eumenes of Pergamum founded a rival library in his capital. Both kingdoms were wealthy and the two libraries competed for sensational finds.

In 197 BCE, King Ptolemy V Epiphanies took the rivalry to a new level by putting an embargo on papyrus shipments to Pergamum. The idea was that without papyrus, scholars in Pergamum could not make scrolls and therefore could not copy manuscripts. The Pergamum library would be crippled.

In response, Pergamum turned to a more expensive, but more durable, material made from the skin of sheep and goats. We know it as parchment, from the medieval Latin phrase for “from Pergamum”.

Librarians are a resourceful lot.

* “Where?” you ask. Here:

As you can see, not a small place.

** Alexandria kept the originals*** and gave the owners the copies. Piracy of intellectual property is not new.

*** According to Galen, they were catalogued under a special heading: “books of the ships”.

November 6, 2025

Boat Trip Through History: A Stop at the Papyrus Institute

Over the years, I have gone to many, many living history sites at which people in period costume demonstrate blacksmithing[1], quilting, weaving, making soap, and cooking in a pre-modern kitchen. Even when it is a traditional skill that I have seen demonstrated many times before, I always come away with a sense of amazement.

I did not expect to have a similar experience at the Papyrus Institute.

In many ways, the Papyrus Institute reminded me of the rug workshops that are an unavoidable stop in any country with a handwoven rug industry, in which the “lesson” about rug weaving is only a pitch for selling rugs.[2] And in fact, the “institute” was clearly designed to sell tourists the works made on papyrus that hung on its walls[3] —better quality and much more expensive than those sold in the small bazaar that surrounded every monument we stopped at but still obviously designed for the tourist trade.

There was no attempt to evoke the past. In fact, the counter at which a staff member demonstrated making papyrus reminded me of a high school science lab station, as did the demonstrator’s presentation style. He spoke briefly about the symbolic significance of the papyrus plant as the heraldic emblem for Lower (i.e.) Egypt.[4] Then he took us through the steps of making papyrus paper —slowly, carefully, calmly.[5] Fibrous layers were removed from the stem of the plant in strips. The strips were soaked and then laid side by side in two layers: one layer laid lengthwise, then topped by another layer at right angles to the first. The two-ply stack was then pressed together; as it dried the glue-like sap of the plants cemented the layers together, creating a sheet of paper.[6]

To my surprise, it was absolutely fascinating.

Payprus document ca 1900 BCE

Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Art Museum

A few other papyrus tidbits:

The earliest extant piece of papyrus is a blank scroll from around 2900 BCE.The first examples with text date from about 2500 BCE, which is about the same period as the earliest known statue of a scribe.Although paper is the best known use of the papyrus plant, ancient Egypts, also used it to make small boats, mats, boxes, baskets, sandals, and ropes, similar to the way birch bark was used in North America.Papyrus could be erased and reused.

[1] Eternally fascinating as far as I am concerned Almost magical.

[2] We made that stop several days prior to visiting the Papyrus Institute. Watching a rug maker at work was interesting the first time I saw it, but it doesn’t continue to grip me the way blacksmithing does.

[3] And yes, I succumbed to a very appealing landscape that I need to have framed.

[4] It is worth pointing out that the Nile flows north to the Mediterranean, not south. So when you take a boat ride down the Nile, you go north. This may feel wrong, but it is true. Look at a map if you don’t believe me.

[5] One of the variations of a mantra that our guide repeated many many times a day as we walked on uneven surfaces through a gauntlet of vendors selling papyrus bookmarks and fake alabaster statues. (In retrospect, I regret not buying a pack of the bookmarks, which were ten for a dollar. I go through a lot of book marks)

[6] I am missing a step or two, but you get the idea.

November 3, 2025

Boat Trip Through History: The Temples at Abu Simbel

When we sat down to review the materials from the tour company for our Egypt trip, my BFF from graduate school and I had to make several choices about optional excursions that weren’t included in the basic trip.[1] The biggest of those excursions was an all-day trip to the temples at Abu Simbel. (Including a couple of flights in a prop plane!) As far as we were concerned, it was an immediate yes. It was definitely worth it.

Unlike most the of the Egyptian temples we saw, which were built from blocks of stone transported from the quarries of Gebel Silsila,the temples of Abu Simbel were carved out of the mountainside. They were commissioned in the thirteenth century BCE by the pharaoh Ramses II, aka Ramses the Great,[2] as a monument to himself and the first of eight Royal Wives, Queen Nefertari (b. 1301 BCE).[3] (They married before he became pharaoh and the sources suggest it was a genuine love match.)

Time passes even if you’ve styled yourself “the Great.” Over the centuries the temples fell into disuse and were slowly buried by sand.

Abu Simbel was rediscovered[4] in 1813 by Swiss explorer Johann Ludwig Burkhardt (1784-1817), who saw the top frieze of the main temple sticking out from the sand. Five years later, excavation of the temples began after Italian archaeologist Giovanni Belzoni[5] (1778-1823) located an entrance to the temple.

The temples at Abu Simbel are astonishing. Ramses II’s temple is dedicated to the sun gods Amon-Re and Re-Horakhte. (Nefertari’s smaller temple is dedicated to the worship of the sky-goddess Hathor. )Two enormous seated statues of Ramses II sit on either side of the main entrance to the temple. Three consecutive inner halls, decorated with pictures celebrating events in Ramses reign, extend 185 feet into the cliff.[6] The truly extraordinary feature of the temple is that it was designed in such a way that the first rays of the morning sign penetrate its inner chamber twice a year near the equinoxes— highlighting the faces of three of the four gods portrayed therein, Amon-Re, Re-Horakhte, and Ramses II in his persona as the living incarnation of Re-Horakhte on earth. The fourth guard, Ptah, the god of darkness remains unlit.

The fact that the temples can still be seen is equally astonishing.[7]

In the 1960s, the pending construction of the Aswan High Dam,threatened Abu Simbel and other Nubian antiquities with inundation in the giant artifical reservoir that the dam would form, now known as Lake Nasser. UNESCO spearheaded an international effort to save the monuments, described by André Malraux, the French Minister of Culture as “a kind of Tennessee Valley Authority of Archeaology.” It was the organization’s first major campaign since its formation in 1945. Some thirty countries formed national committees to support the operation; more than fifty countries donated money to the effort.

Several plans for saving Abu Simbel were proposed and rejected before a solution was accepted. It required engineering on a heroic scale: The team dug away the top of the cliff and then dismantled the temples, cutting them into more than one thousand blocks, each of which weighed some thirty tons. They reassembled the temples on an artificial cliff that was 180 miles inland and 64 miles above the original site, carefully aligned to reproduced the biannual entrance of light into the inner chambers.

Relocating Abu Simbel was the most dramatic portion of the Nubian Campaign. Over the course of twenty years, forty separate technical missions, drawn from across the world, saved a total of twenty-twomonuments and complexes from inundation. The last monuments to be moved were the temple complex at Philae, built in honor of the goddess Isis around 370 BCE.

In 1979, the rescued monuments were designated a UNESCO world heritage site.

[1] Though in all fairness, there was nothing basic about any of it.

[2] What made him great? In part the fact that he really, really, liked to build monuments to himself telling us how great he was. Victorian travel writer Amelia Edwards summed it up in her 1877 account A Thousand Miles Up the Nile: “We know now that some of the pharaohs were greater conquerors. We suspect that some were better rulers. Yet next to him, the other seemed like shadows…His features are as familiar to us as those of Henry VIII or Louis XIV.” —Two other rulers with big egos, I might point out.

[3] Not Nefertiti (ca 1370-1330 BCE), who was the great royal wife of King Akhenaten.

[4] A world that always sets off warning bells for me. Obviously local residents were aware that something was there.

[5] Using the term archaeologist to describe Belzoni is a bit of a stretch. He had a passion for collecting antiquities, without regard to their significance, and caused plenty of damage to the sites in the process of getting them.

[6] Roughly the height of the Leaning Tower of Pisa or the Cinderella Castle at Disney World. Or if you insist on the usual comparison: a little more than the width of a football field.

[7] If you want to read a detailed account of the story of how the temples were saved, I strongly recommend Empress of the Nile by Lynne Olson.

October 30, 2025

Boat Trip Through History: Cairo’s City of the Dead

(As close as I can get to a spooky story for Halloween this year)

The down side of traveling through a foreign country with a tour is that occasionally your guide mentions something fascinating in passing that is not part of the day’s tour. It is never mentioned again, and the curious history nerd is left to find out more on her own. Case in point: on our way to the Step Pyramid at Sakkara, our guide gestured and said, more or less, “On the left[1] is the City of the Dead. It is a complex of historic Islamic cemeteries[2] where thousands of families live in and among centuries old tombs and mausoleums.” My ears perked up. And then we moved on.[3]

Photo credit Daniel Nussbaum

The City of the Dead is huge: four square miles in the original core of the city that encircle the Cairo Citadel to the north and south. The earliest section of the necropolis dates from 642 CE, when Muslim Arabs led by Amr ibn al-As, one of the companions of Muhammad, conquered Egypt. It reached its height during the period when the Mamluks ruled Egypt, from the thirteenth through the fifteenth centuries. It contains the graves of common people as well as elaborate mausoleums and tomb complexes built by Cairo’s elite.

People have always lived among the tombs. In the earliest periods, most of the living inhabitants had jobs related to the necropolis: grave diggers, the craftsmen who built the more ornate structures, tomb custodians, and Sufi mystics and scholars who studied in religious complexes attached to some of the most important mausoleums. Over time, small urban settlements in the area, and their residents, were absorbed by the necropolis, creating pockets of residential neighborhoods among the tombs.

Beginning in the late 19th century, the use of the cemeteries by the living increased as a result of rapid urbanization and housing shortages. Some squatted in tombs. Some moved into their own families’ tombs, particularly after the destruction of the 1992 earthquake. More constructed unofficial housing wherever they could find space.

In the course of learning more about the area, I discovered that the City of the Dead is a wonderful place to take a walking tour, with no aggressive vendors or souvenir shops trying to sell you fake papyrus bookmarks[4] and other tchotchokes. There are restored mosques, mausoleums and other medieval Islamic architecture to explore, street murals, and a cultural center that hosts artsy events and concerts, as well as walking tours with local guides. It’s also a chance to see Egyptian life up close in a way that our tour didn’t manage.

Maybe I need to go back to Cairo after all.

[1] Or possibly on the right.

[2] Many of the sources I looked at described the region as a group of cemeteries and necropolises. I immediately headed down a little rabbit hole to find out what the difference is between the two. As best I can tell, a necropolis is a large elaborate cemetery, usually attached to an ancient city.

[3] Over the coming days, we were introduced to many examples of people living in or near the ruins of ancient temples that had been half-buried by the sand. And why not? Ancient monuments were really well built—thanks to the back-breaking labor of thousands.

Moreover, stone is hard to come by in the desert. Most of the stone used in ancient Egypt was cut from sandstone quarries in the Silsila Mountains (Gebel Silsila) on either side of the Nile and then floated down river to Luxor. Gebel Silsila was also an important center for the cult of the Nile. The ancient Egyptians made sacrifices at this point of the river at the time of the yearly floods to ensure the fertility of the land. As a result, the quarries are home to shrines of all sizes and memorial stelae.

The west bank of Gebel Silsila is open to tourists. Alas, we saw it only in passing from the boat. (See downside of traveling with a tour, above)

But I digress.

[4] More on papyrus in a later post.

October 27, 2025

Boat Trip Through History: Imhotep and the Step Pyramid at Sakkara

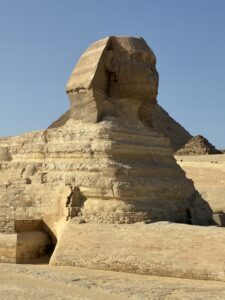

Day two in Egypt: The stepped pyramid at Sakkara, the Great Pyramid at Giza, and the Sphinx. (Plus some tombs with amazing wall paintings and a close encounter with a camel)

I don’t have much to say about the Great Pyramid or the Sphinx. My takeaway was that the Great Pyramid is more imposing in real life and the Sphinx less so.[1]

The Step Pyramid is another story. Or more accurately, it has a story attached to it.

Most architects of the ancient world remain anonymous. We are more apt to know the name of the king who ordered a building than the man who designed it. In ancient Mesopotamia, for instance, kings had their names impressed in the brick used in the great buildings they commissioned. The first architect whose name was recorded was an Egyptian, Imhotep, the man who designed the Step Pyramid at Sakkara.

Egypt’s first major monuments, built during the First and Second Dynasties (3200-2780 BCE), were mud-brick tombs known as mastabas. Mastabas were rectangular structures with sides that sloped inward toward a flat top, built above burial chambers cut through the desert sand and into the bedrock below. Each tomb contained a chapel that held offerings for the deceased to use in the afterlife and a secret room where a statue of the deceased was stored. The interiors of the mastabas themselves were little more than narrow corridors surrounded by a solid core of rubble

In 2780 BCE, the Pharaoh Zoser founded a new dynasty and a new era of Egyptian history: the Old Kingdom, possibly the most brilliant period in pharaonic Egypt. When the time came for him to plan his funeral monument, he wanted something larger and grander than the mastabas of his predecessors. He turned to Imhotep, his chief officer and vizier, to build it for him. Imhotep took the basic form of the mastaba and transformed it something new and thrilling.[2]

Zoser’s Step Pyramid is generally considered to be the beginning of true stone architecture. It is the first building known to have been constructed with stones shaped into precise rectangular blocks. In earlier stone walls, the shape of each stone can be separately identified; Zoser’s pyramid was built with limestone blocks that were carefully fitted together with minimal joints into a smooth continuous surface. The Step Pyramid itself can be seen as a stack of stone mastabas: six immense tiers tower 200 feet high over the granite-lined burial shaft beneath it. It was more like a Mesopotamian ziggurat in shape than the classic Egyptian pyramid.

The shape was new, but many of the details were familiar. In creating Zoser’s pyramid, Egyptian builders, under Imhotep’s direction, took designs, details, and techniques previously used in buildings made from wood, reed, and mud brick and rendered them in stone. They set stone blocks in the same mortar pattern they had previously used for brick buildings. They copied the bundles of papyrus reeds that gave added strength to mud brick walls, creating engaged stone columns–one of later architecture’s basic components. The shaft of each column imitated the plant’s triangular stem. The capital at the top of each shaft was shaped like the open cluster of papyrus flowers or a lotus leaf.

In recognition of his achievements, Zoser gave Imhotep an honor no artist had received before him: a place in history. At Zoser’s order, Imhotep’s name and titles, including “chief of sculptors,” were carved on the base of a statue of the pharaoh.

In addition to being an innovative architect, Imhotep was a scholar, priest, astrologer, magician, and physician. His skill as both an architect and a physician led him to be recognized as a deity. During his lifetime, he was named the son of Ptah, the patron god of craftsmen who created the universe. Two hundred years after his death, Imhotep was worshiped as the god of medicine in Egypt and in Greece, where he was identified with the Greek god of medicine, Aesculapius.

Image of Imhotep from the 5th century BCE. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

[1] You’ll have to take my word for it. The impact doesn’t come through in my photographs.

[2] With the help of who knows how many hundreds of thousands of hard-working laborers sweating in the heat and dust. According to Herodotus, it took 100,000 men working in three-month shifts twenty years to complete the Great Pyramid at Giza (ca. 2550 BCE). Since he was writing 2000 years after the fact, we have to take the number with a pyramid-sized grain of salt.