Matthew Landis's Blog

June 1, 2019

The End Is Near. But Not Really.

Here is a truth: I love doomsday stories. I’ve always wanted to write one. Think a teenage version of The Road, maybe with zombies. Definitely motorcycles. A couple years ago I stumbled upon Charlie Higson’s The Enemy series and sobbed for days that he beat me to it. Then I binged a season of The Walking Dead and felt better.

I needed to forge my own direction—end the world my way. For a while, I wasn’t entirely sure what that was. I kept reading scary doomsday books (if you want to live in eternal dread, read One Second After by William Forstchen). And then this really interesting question floated up from the Ether: What if the apocalypse didn’t happen? What an epic letdown that would be, right?

This seemed funny—a reverse engineering of the whole thing. I was hooked. My brain went into overdrive with possibilities. I envisioned a kid convinced the world was ending only to find out (awkwardly) that the doomsday predictions he believed so completely turned out to be bogus. It felt ironic and weird and yet also sort of deep, the type of story that could explore some other stuff that was on my heart. It felt like me.

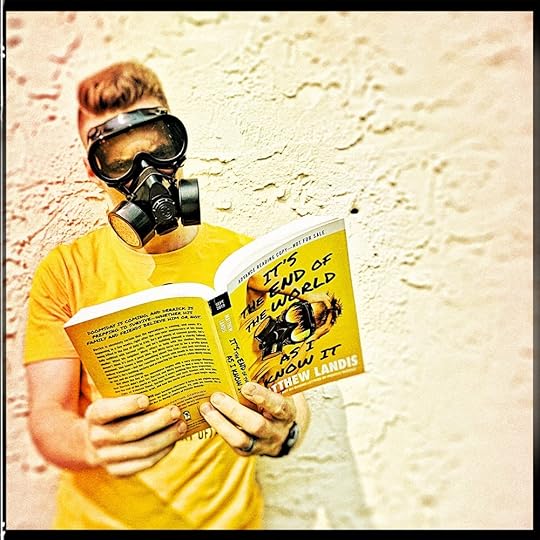

And so began the origin of my third novel, It’s the End of the World as I Know it. Like its predecessor, The Not-So-Boring Letters of Private Nobody, the story is set at the fictional Kennesaw Middle School—a virtual copy of the school I teach at in the Philly suburbs.

Yet unlike that book, it has zero to do with social studies. Nor are there zombies or motorcycles or long, dangerous roads to the sea. Just an 8th grade kid, Derrick, who’s been turning his backyard shed into a doomsday shelter for the better part of a year. Convinced the Yellowstone super volcano is set to blow on September 21st (nineteen days from the book’s opening), Derrick will not be caught off guard. He will survive The End, due in no small part to his not surviving the other apocalypse in his life: his veteran mom’s death in Iraq.

In my twelve years of teaching middle school, I’ve had many kids with parental death. Too many. I don’t honestly know how they bear it—but they do, and it is quite something. I wanted to tell you about them, let you imagine the trauma of sudden and permanent loss they endure—“doomsday” if there ever was such a thing. I wanted to sketch the supporting players: the surviving parent and other sibling. The guidance counselor and therapist. The friend.

I’ve also had a student, equally amazing, who endured a potentially fatal illness. What was that like, I wondered—to have survived this “end”? How does peeking behind the curtain change the way a kid lives? This inspired Derrick’s foil and friend in the novel, Misty, fresh off a kidney transplant that nearly took her off the map before the game really got going. I pictured her just getting started with life as Derrick was getting ready for The End—her trying to cram it all in while he was packing it in. The intersection of those paths became the arc of this book. There’s also some poop jokes, a python that gets loose, and Pop-Tarts. Lots of Pop-Tarts.

I still love the gritty survival story set in a world-gone-to-hades (should you also, go read American War by Omar El Akkad, it’s fantastic). But that is not this book, because I’ve been learning that real life has plenty of actual apocalypses. It’s The End of the World As I Know It is about two kids surviving their own doomsdays and facing the changes it wrought in them. It is a story of friendship, grief, and the many ways the world can end—and begin again.

Did you know this book is available to preorder on Amazon and Audible ? It is. Do it.

Check out this list of amazing/terrifying apocalyptic books.

April 10, 2018

Yes, The Civil War Was About Slavery

Original seal of the Quaker-led Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade, founded in Philadelphia, 1787. Inscription: "Am I Not A Man And Brother?" http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part2/2h6...

This Thursday, April 12, marks the 157th Anniversary of the Civil War’s beginning. What follows is hardly comprehensive, but a mirrored version of the “Causes” unit my 8th graders get. As is often paraphrased in my room, “Misremember the past and you jack up the future.”

1819: Missouri wants statehood as a SLAVE state, which will upset the free/SLAVE state balance in Congress. Rep. Livermore’s (NH) argues, “An opportunity is now presented...to prevent the growth of a sin [SLAVERY] which sits heavy on the souls of every one of us.”[1]

1820: Congress is deadlocked over Missouri. Rep. Cobb (GA) says, “If you persist, the Union will be dissolved. You have kindled a fire which a sea of blood can only extinguish.” Congress eventually lets in Missouri as a SLAVE state but adds Maine as a free state to retain Congressional balance.[2]

1831: Nat Turner’s SLAVE rebellion causes Southerners to crack down on anti-SLAVERY pamphlets. Mississippi offers $5,000 bounties for capturing abolitionists who share such info—or even speak against SLAVERY.[3]

1832: South Carolina threatens armed resistance to the collection of a federal tariff during the Nullification Crisis. President Andrew Jackson writes, “the tariff was only a pretext, and disunion and southern confederacy the real object. The next pretext will be the negro, or SLAVERY question.”[4]

1836: Flooded by anti-SLAVERY petitions, Congress puts a gag order on SLAVERY debates. (For an exhaustive and epic account of John Quincy Adams’s heroic war against the gag, see James Traub’s MILITANT SPIRIT.)[5]

1849: California applies for (free) statehood; Southerners balk at the potential balance upset. Sen. Calhoun (SC) asks Congress, “What is it that has endangered the Union? To this question there can be but one answer,[6]

--that the immediate cause is the almost universal discontent which pervades all the States composing the Southern section of the Union...It commenced with the agitation of the SLAVERY question and has been increasing ever since.”[7]

1850: Congress compromises: California admitted as a free state; Utah/New Mexico vote on SLAVERY themselves; the SLAVE trade is banned in D.C.; a strict fugitive SLAVE law with fines and prison sentences for Northerners who aide runaway SLAVES or obstruct their recapture.[8]

1851: Tension over the fugitive SLAVE act grows as Northerners feel it makes “SLAVE catchers of us all” (Ralph Waldo Emerson). Only a fraction of fugitive SLAVES residing North are returned, stoking Southern resentment.[9]

1852: Ohian Harriet Beecher Stowe publishes the novel UNCLE TOM’S CABIN, exposing the brutality of slavery. Virginian Martha Haines Butt publishes a rebuttal novel, ANTIFANATICISM: A TALE OF THE SOUTH that portrays SLAVE HOLDERS as benevolent and SLAVES as grateful, loyal subjects.[10]

1854: Congress passes the Kansas-Nebraska Act, allowing citizens of Kansas and Nebraska to vote on SLAVERY in those territories. Northerners are outraged, as the law abolishes the Missouri Compromise provision that banned SLAVERY above the 36 30’ line.[11]

1856: AntiSLAVERY and proSLAVERY forces flock to Kansas and clash during fraudulent elections. Abolition extremist John Brown brutally executes five proSLAVERY leaders at Pottawatomie Creek. Rep. Brooks (SC) beats Sen. Sumner (MA) nearly to death on the Senate floor as punishment for his anti-SLAVERY speech “The Crime Against Kansas.”[12]

1857: Chief Justice Taney makes historic ruling against Missouri SLAVE Dred Scott: 1) SLAVES are not, were not, and cannot become citizens; 2) SLAVES brought into free states are still SLAVES because the Missouri Compromise is unconstitutional. “A wicked and false judgement” writes the New York Tribune. Slaveholders delighted.[13]

1858: Rep. Lincoln (IL) challenges Sen. Douglas (IL) for the Illinois Senate seat via public debates, widely reprinted. Lincoln argues: SLAVERY is morally wrong; SLAVERY must not spread; SLAVERY should be left alone in Southern states; a SLAVE power conspiracy of Southern elites is controlling Congress.[14]

1859: John Brown raids the federal arsenal at Harper’s Ferry, VA to ignite slave rebellion; plan fails. At his execution Brown says, “The crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood.” Many Northerners hail Brown a martyr, increasing Southern animosity.[15]

Nov. 1860: Lincoln wins a divided election without carrying a single Southern state. Promises not to “make any attack...on the domestic institutions of any state.”[16]

Dec. 1860: South Carolina secedes from the Union, declaring Lincoln “hostile to SLAVERY” and ready to wage war “against SLAVERY.” Accused North of “denouncing as sinful the institution of SLAVERY” and refusing to follow federal law regarding SLAVERY. Thus, South Carolina feels “released from it’s obligation” to the Union.[17]

Feb. 1861: Six other states secede (Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Texas). SLAVERY features heavily in these declarations.[18]

March 1861: In inaugural speech, Lincoln says, “I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of SLAVERY in the States where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so.” Other incendiary comments regarding SLAVERY abound.[19]

April 12 1861: Confederate forces fire on the federal-occupied Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor. The war begins.[20]

Sources:

[1] Diane Hart and Bert Bower, History Alive! : The United States Through Industrialism (Palo Alto, CA: Teacher's Curriculum Institute, 2011), 403.

[2] Ibid, 404.

[3] Ibid, 405.

[4] Scott Bomboy, "Andrew Jackson’s conflicted history on North-South relations," The National Constitution Center, last modified May 2, 2017, accessed April 9, 2018, https://constitutioncenter.org/blog/a....

[5] Hart and Bower, History Alive!, 405. Seriously read Traub’s MILITANT SPIRIT. That book will give you a new-found appreciation for the often forgotten John Quincy Adams.

[6] John C. Calhoun, "The Compromise," The Congressional Globe (Washington, DC), Senate, 31st Congress, 1st Session, [Page #], accessed April 9, 2018, https://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage....

[7] John C. Calhoun, "The Compromise," The Congressional Globe (Washington, DC), Senate, 31st Congress, 1st Session, [Page #], accessed April 9, 2018, https://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage....

[8] Hart and Bower, History Alive!, 406-408.

[9] Ibid, 408.

[10] Ibid, 408-409. Butts jaw-droppingly racist novel can be read in entirety here - http://utc.iath.virginia.edu/proslav/butthp.html

[11] Hart and Bower, History Alive!, 409-410.

[12] Ibid, 411.

[13] Ibid, 412-413.

[14] Hart and Bower, History Alive!, 414. For the full text of these seven debates, see Northern Illinois Univeristy, "The Lincoln-Douglas Debates," Lincoln Library, last modified 2014, accessed April 10, 2018, http://lincoln.lib.niu.edu/lincolndouglas/debatetext.

[15] Hart and Bower, History Alive!, 414-415.

[16] Ibid, 415. See Lincoln’s attempt to appease the South see Eric Foner, The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery (New York: W.W. Norton, 2010), 163.

[17] Yale Law School, Lillian Goldman Law Library, "Confederate States of America - Declaration of the Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina from the Federal Union," The Avalon Project: Documents in Law, History, and Diplomacy, last modified December 24, 1860, accessed April 10, 2018, http://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/csa_scarsec.asp.

[18] The Civil War Trust, "Primary Source: The Declaration of Causes of Seceding States," Civil War Trust, accessed April 10, 2018, https://www.civilwar.org/learn/primary-sources/declaration-causes-seceding-states.

[19] Abraham Lincoln, "First Inaugural Address of Abraham Lincoln," The Avalon Project: Documents in Law, History, and Diplomacy, last modified March 4, 1861, accessed April 10, 2018, http://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/lincoln1.asp. For other incendiary speech points, and Southern response, see Foner, The Fiery, 157-159.

[20] Hart and Bower, History Alive!, 416-417. For northern reaction on slave vs. free societies see Foner The Fiery, 163.

August 2, 2017

We Should All Be More Like Teenage Benedict Arnold

The English poet Christina Rossetti once said, “Life is not sweet.” A teenage Benedict Arnold would agree.

Born into a legit, New England elite family with strong Puritan traditions, Arnold was expected to be awesome—a leader in business, community, and church. For the first decade of his life, things were looking pretty good: He was at a solid school, his dad was making money, and the Arnold name meant something in Norwich, Connecticut.

But his world started falling apart.

Between the ages of ten and twenty, Arnold experienced catastrophe: His father lost the family business, became an alcoholic, and got excommunicated from the church—all giant, horrible embarrassments in a New England society of rigid class structure. And then Arnold’s mom died. Then his dad. Actually all of his immediate family passed away, except for one sister.

Told you so, Christina Rossetti would write eighty years later.

But Colonial-era-guts and good old Puritan dogma don’t allow a person to collapse under the weight of life not being a joy ride. Instead of pouting, Arnold moved to another New England town—New Haven, Connecticut—and started a new mission to regain all his father lost. Within three years, he was running a crazy-successful bookstore and spending tons of time on the trading ships of his business partner and local merchant, Adam Babcock. Arnold’s most baller move during Mission: Bring Back the Arnold Name was rebuying his family’s foreclosed home in Norwich—and then reselling it for a profit. That could have been a purely financial move, but historian Jim Murphy hints that this was of an in-your-face, old-community-that treated-us-like-crap move. I tend to agree.

So the question is: Does knowing Arnold’s hardships as a teen help us understand his decision to betray America as an adult? That’s a dangerous query that opens historians to arm-chairing this whole thing; human motivations are complex and hard to nail down. But if you asked me directly, and my grad school professors weren’t around, I’d say “yes, most definitely” because the two key markers of whether a person is prone to commit treason (according to the CIA) are psychology and circumstance. As the Revolution unfolded, and Arnold saw his reputation and personal finances crumble due to perceived and actual sleights, it could be argued that he again felt his family’s honor slipping away. When push came to shove, he was going to side with whomever would grant him what he had fought so hard to get: the mad respect he was due.

Teenage Benedict had true grit. While sources are scant on how exactly he felt during those tumultuous years, it’s easy to imagine the sorrow and helplessness. But what’s harder to consider is someone today being able to summon the effort to get up when the perils of a not-sweet-life kept running them over. I’d like to be more like teenage Benedict Arnold, but pray I’m spared the circumstances that forge such endurance.

So here’s to reclaiming familial honor by forging your own way—just be careful that way doesn’t inadvertently lead you to infamous treachery. RIP, teenage Benedict.

Sources:

Details of Arnold’s life can be found in a million places, but I relied on Jim Murphy’s super-readable The Real Benedict Arnold (New York: Clarion Books, 2007). The CIA’s recently declassified study in treason I referenced can be found here - https://www.cia.gov/library/readingro..., and the Rossetti work I quote is called “Life and Death.” It's super depressing, but real, which is why I love it.

July 7, 2017

Why Do People Commit Treason?

As I get ready to launch my debut novel, I’ve been obsessing about the story’s heart: the burden of inherited treachery. The characters in my book descend from figures in American history who did some pretty shameful things, which has me thinking about a bigger question: Why do people commit treason? Some light research and my own opinion yielded two reasons.

1. People commit treason because they are deeply unhappy.To quote a recently declassified CIA study on the psychology of treason, "Defection...is the act of a person who feels compelled to do it out of dissatisfaction, disillusionment, depression, or defeat...a response to an acute overwhelming life crisis or to an accumulation of crises or disappointments.”[1]

These disappointments could literally be anything, from pretty boring to super grand. In my novel, seventeen-year-old Jasper is the modern descendant of Benedict Arnold, probably the most famous traitor in American history. While it’s hard to know what exactly pushed Arnold over the edge, we know that he felt like his battlefield heroics had been ignored (dissatisfaction), he could barely walk after almost losing a leg at those battles (depression), and a high profile Patriot named Joseph Reed had really embarrassed him in a long and public court martial trial (defeat).[2] Again, to quote that CIA report, “...individuals often feel forced to act.”[3]

But all that “unhappiness” really falls into the bigger category of “self-interest”, which is to say that

2. People commit treason because people are basically all about themselves.Now, it’s not a surprise that people are all about themselves, or that that impulse leads them to do bad stuff. Just examine every dictator, ever. Self-interest motivates most, if not all, criminals, and while it’s very simplistic (people do bad stuff for very specific reasons or situations), selfishness is usually behind it.

But if self-interest motivates people to commit treason, why do some people give into that desire, and others don’t?

The answer seems to be a person’s circumstance and preexisting psychology.[4] For example: how dissatisfied are you in a given situation, and how well did your parents model certain traits, like loyalty or grace? That CIA report has a handy formula if you’re interested in figuring out your own likelihood to commit treason, and while it is by definition a “rough equation”, it might be helpful to see if, given the circumstance, you’d turn on those you once held dear.[5]

We All BetrayMost of us will never be in a position of great power, fame, and potential vendetta holding like Arnold; but we still dabble in treachery—like when your friend tells you something, and you absolutely swear to never tell anybody else because that would be, like, so gossipy.

And then you do.

You betrayed a confidence for a few seconds of fame—of being in the spotlight when you spill that secret to other people that you definitely shouldn’t. That betrayal isn’t the grand, political kind, but it comes from the same self-interest.

Maybe instead of asking why people commit treason, we should really be asking why are we so surprised that people commit treason, when life constantly puts us in circumstances that require us to sacrifice our self-interest for others. I think this is sort of what George Washington meant when he was trying to process Arnold’s betrayal: “Traitors are the growth of every country, and in a revolution of the present nature it is more to be wondered at that the catalogue is so small than that there have been found a few.”[6]

To ConcludeIf it is true that a) We are all prone to varying degrees of situational unhappiness and b) Self-interest motivates most of our desires, then it would seem that none of us are immune to acts of treachery, great or small. The ‘treason gene’ doesn’t exist because the trait is already universal: our natural propensity to betray, added to the degree to which we believe the legitimacy of our own self-interest might determine whether or not we follow in the footsteps of traitors like Arnold.

But one truth doesn’t negate another: traitors are the worst.

So don’t be one.

_____________

Matthew Landis is a middle school history teacher and young adult author. His debut novel, LEAGUE OF AMERICAN TRAITORS, will be published on August 8th 2017 by Sky Pony Press. Read more about him and his books and how writing is like building a taco at www.matthew-landis.com .

Sources:

[1] Psychology of Treason, report no. 0006183135, FOIA Collection; Declassified Articles from Studies in Intelligence: The IC’s Journal for the Intelligence Professional, 2, https://www.cia.gov/library/readingro....

[2] Jim Murphy, The Real Benedict Arnold (New York: Clarion Books, 2007), 186. This passage gathers them loosely, but see the rest of Murphy’s book for specifics on Arnold’s treachery. For specifics into the role of Joseph Reed and his court martial, see Arnold-expert Nathaniel Philbrick’s piece "Why Benedict Arnold Turned Traitor Against the American Revolution," Smithsonian, May 2016, accessed July 7, 2017, http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history....

[3] Psychology of Treason, 2.

[4] Ibid, 3.

[5] Ibid.

[6] As quoted Murphy, The Real, 215.

April 30, 2017

SNEAK. PEAK.

In 10 days—on May 10th—I'll be posting the first TWO chapters of my debut YA thriller, LEAGUE OF AMERICAN TRAITORS, on Wattpad.

Why May 10? Because that's when Arnold officially started to get his treason on with British spy John Andre way back in 1779.

So: follow me on Wattpad (@Matthew_Landis) or just check back here on May 10 for the link.

No treason until then.

Seriously.

Thanks!

- Matt

The League of American Traitors

April 4, 2016

I did a Social Media fast. Here's what happened.

The week before Easter, my writing buddy and possible catfish, Dave Connis, suggested we disconnect from the two most time-consuming social media platforms: Twitter and Facebook. We did it for different reasons, had different experiences, and decided on different strategies moving forward. Here’s my side.

Why: Because I had a sneaking suspicion that I looked to Social Media to fill some hole in my life, but deep down I knew it wasn’t really working.I probably check Twitter two hundred times a day with one overriding purpose: validation. Could be a new follower, a “heart” on something (supposedly) hilarious I said, or a mention—anything to let me know what I so desperately hoped to be true: that I am awesome. That I am funny, desired, sought after. That what I am doing with this whole writing thing matters and makes me important. Validation.

But I wondered: if Twitter could do that, why wasn’t it actually doing that for longer than 10 seconds? Meaning: Why did the small bits of validation which resulted from my perpetual Twitter checking not result in any long term validation—a peace, or sorts? More worrisome was this question: Why did I actually feel more anxious the more I was on Twitter? I realized these are all good questions for my therapist, but they were more important questions to directly ask myself. Maybe they’re important questions to ask yourself too. I’m sure the answers will differ, as you and I probably struggle with different strains of whatever this is, but it might help to expose some underlying issue. For me that issue was a deep and abiding insecurity I hoped Twitter would abate, but which it in fact exacerbated. So I decided to take a break.

The experience: Like the sweet relief of a long hoped for bowel movement.It was almost as if my soul was craving to be starved from Twitter, which might not actually make any sense. But it’s true: the relief was undeniable. It rushed in immediately when I deleted the app from my phone and grew over the next ten days. Yeah, I felt unconnected, but within a day I realized that the connection didn’t really matter for the overarching narrative of my life. I’m not saying Twitter is inconsequential—though it’s fo shizzle less consequential than we’re all making it. I’m saying that the place it had in my life was suddenly exposed to be unimportant. More specifically, the fast exposed Twitter as an obstacle to real peace. My anxiety over how funny/awesome/likable people think I am dropped significantly. I no longer wasted valuable mental space crafting (supposedly) clever tweets whose reception I later agonized over. My phone competed far less with the attention of things that actually mattered, things I was taking for granted. I Snapchatted a lot more.

Avoiding Facebook gave me another type of relief: a break from my cringingly shameful condescension. While fasting, I couldn’t fall into my default mode of “judge the crap out of pretty much everybody” for posting things that I’d never post out of fear people would judge the crap out of me. That is to say: I was unable to project my natural insecurities onto others because I wasn’t giving the worst version of myself repeated opportunities to do so. And yes, I missed out on some cool stuff that probably happened (like a bagillion people wishing me happy birthday), but to be completely honest, I didn’t feel like I missed a thing. I felt free.

Moving forward: I will occasionally swim in the Social Media ocean instead of purposefully drowning myself in it.I can’t avoid Twitter or Facebook forever, and I don’t think I should; actually, I’m not legally allowed to according to a strict reading of my publishing contract. I also can’t dismiss the great things the platforms bring: without Twitter, I’d never have met Dave. Yes, he's probably a forty-eight-year-old Norwegian expat having a hilarious time catfishing me from his basement apartment in Denver, but the friendship has given us a space to share the ups and downs of an industry that is, at times, the very definition of soul crushing. I rely on that, and I have it because of Twitter.

My plan is modest: to check in on social media once a day, for no longer than it would take a moderately in shape person to run a mile. Eight minutes, say. Maybe nine. I’m sure this will ebb and flow as life happens, but it’s a good start for me. I just can’t continue on like I was because the fast proved something deeply convicting: that which I seek to make me whole often leaves me a little more hollow.

And with that, I’m off to binge DareDevil Season 2 on Netlfix.

October 22, 2015

Deifying the Founders Actually Lessens Their Legitimate Greatness

I grew up thinking Jefferson was pretty much a god. I mean, of course I did, because in middle school I learned that he authored the Declaration all by himself—a gigantic deal, as it’s arguably our country's most important document behind the Constitution. In high school I visited the Capitol and gaped at his monstrously domed memorial. In college I pilgrimaged to Monticello and reverently strolled through his plantation and nearby university. To say that I put Jefferson on a pedestal would be to say that the Arctic was cold: an almost fatally hilarious understatement.

And then I went to grad school.

Suddenly, Jefferson became more complex. I learned that other colonial legislatures had declared their independence from England prior to Jefferson’s document, and that he didn’t write it alone (a committee helped edit, including Adams and Franklin, followed by a further Congressional hack job).[1] I uncovered a self-promoting Jefferson, who masterfully participated in making sure posterity remembered his Declaration.[2] I encountered a profoundly hypocritical Jefferson, seen most annoyingly in his elusive habit of playing hide and seek with his conscience (among these, bemoaning the evils of slavery while perpetuating the practice).[3] And I discovered a plantation owner whose estate was not the benevolent rural picture created by historians who were blatantly burying primary source material that highlighted the Founder’s crueler side.[4]

I wouldn’t say that I was devastated; I was just really disappointed. I’d deified this guy—or rather, he’d been presented to me as deity. And I liked that narrative. It was attractive and comfortable and supremely regal. I inhaled it. I washed it down and asked for seconds. The only problem was that flaws riddled this narrative. But that just created another problem, because the haters—modern observers who gleefully, albeit correctly, decry Jefferson’s glaring faults—also ignored his deserved accolades.[5] That is to say, the backlash of hard truths that tore down Jefferson’s god-like status inevitably downplayed what originally caused my misguided worship in the first place—further muddling his legacy. Ironically, deifying Jefferson actually ended up lessening the Founder’s legitimate brilliance.

Take this hilarious example: in his mid-twenties, Jefferson fell for his best friend’s wife. He was crushing hard. So hard that he brazenly and repeatedly propositioned her over the course of several years. At a house party he secretly slipped a love note into the cuff of her dress sleeve; at another party, he pretended to feel ill, raced to her bedroom, and tried to bargain his way inside.[6] Let that sink in for a minute. These aren’t the actions of someone who belongs in the Founder Pantheon; they’re embarrassing plot points in the Real Housewives of Colonial Williamsburg.

But I think we’d all agree that to whitewash Jefferson based upon this instance—which we can also all agree was pretty devious—misrepresents him. The story only proves that Jefferson could be a scoundrel. I’m on board with that; I get it. I’m well aware that morality is not a prerequisite for statesmen (see also: JFK sneaking women into the White House). And I agree that examples like this help expose the silliness of deification. After all, deities don’t go around starting illicit affairs (except the Greek and Roman ones, who seemed to rather enjoy it).

But if, in warring against deification, we downplay Jefferson’s accomplishments—that too presents a misleading portrait of the Founder. After all, he did some pretty monumental things. Things like penning The Virginia Statutes for Religious Freedom that would become the forerunner of our much-loved First Amendment.[7] Things like authoring a bill to establish free public education for girls and boys.[8] Things like founding the University of Virginia.[9] Things like revolutionizing gardening techniques and American cuisine.[10] Things that have profoundly changed the political, educational, agriculture, and dietary landscape of this nation.

Since Jefferson was neither deity nor demon, let’s treat him as neither. Let’s treat him as a human, because doing so will a) allow us to fully appreciate his accomplishments and b) still mollify our inherent bloodlust for pointing out others’ hypocrisy. To use Jon Meacham’s summation of another much-maligned president, Andrew Jackson, “Not all great presidents were always good.”[11] This also applies to Jefferson, I think. He possessed astounding intellect across various spectrums, but he was also a hapless hypocrite who formulated mind-numbing excuses to avoid terrible truths. Why does that surprise us? We’re no different. Just because we haven’t tried to lure our best friend’s wife into an illicit affair (hopefully you haven’t, and if you currently are, stop it) or railed against slavery while practicing slavery, doesn’t mean that we’re not of Jefferson’s stock: human stock. Stock deeply flawed. Stock that habitually refuses to practice what we preach. Stock capable of great good, but also great evil.

I get that our acute cynicism, sharpened by enlightened modernity, justly won’t let this hero cult stuff stand. But neither should we get so busy tearing down the god-like status of Founders like Jefferson that we omit their astounding accomplishments. Striking a middle ground will no doubt make both the lovers and haters uncomfortable, but that vantage point provides a far more honest assessment.

[1] Pauline Maier, American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence (New York: Vintage Books, 1997), 48, 99.

[2] Joseph J. Ellis, American Sphinx: The Character of Thomas Jefferson (Thorndike, Me.: G.K. Hall, 2000), 308.

[3] Ibid, 315.

[4] Weincek, Henry. "The Dark Side of Thomas Jefferson." Smithsonian. Last modified October 2012. Accessed October 13, 2015. http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-dark-side-of-thomas-jefferson-35976004/?no-ist.

[5] A Sally Hemings message board on Monticello.org displays some hilarious back forth between the Jefferson lovers and haters—http://www.monticello.org/site/plantation-and-slavery/thomas-jefferson-and-sally-hemings-brief-account

[6] Jon Meacham, Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power (New York: Random House, 2012), 42.

[7] Thomas Jefferson and the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom," Virginia Historical Society, accessed October 21, 2015, http://www.vahistorical.org/collections-and-resources/virginia-history-explorer/thomas-jefferson

[8] Anna Berkes, "A Bill for the More General Diffusion of Knowledge," Monticello, last modified April 2009, accessed October 21, 2015, http://www.monticello.org/site/jeffer....

[9] "Founding of the University," University of Virginia, last modified August 3, 2010, accessed October 21, 2015, http://www.virginia.edu/uvatours/shorthistory/

[10] Peter J. Hatch, "Thomas Jefferson's Legacy in Gardening and Food," Monticello, last modified 2010, accessed October 21, 2015, https://www.monticello.org/site/house-and-gardens/thomas-jeffersons-legacy-gardening-and-food.

[11] Jon Meacham, American Lion: Andrew Jackson in the White House (New York: Random House, 2008), 97.

October 5, 2015

Trying To Get Published Made Me Kind of Miserable

You might find this post disingenuous since I already got a book deal; shelve that cynicism—at least until the end. I’m writing with unfiltered empiricism.

A great struggle in my life has been to pursue something without letting it consume me. Exuberance defines me; I don’t know why, it’s the way I was made. That can be good—like how it motivated me to sprint into a packed lecture hall at Penn State wearing a heart-covered t-shirt and proclaim HAPPY SIX MONTHS to my then girlfriend (now wife). But it can just as easily make me miserable—like when I threw all of myself into trying to get published. Here’s how:

1) Odds were I’d never get published. Less than 2% of completed manuscripts get a book deal. That statistic gnawed at me daily. Why wouldn’t it? The only logical response to this industry standard was crushing defeat—a feeling of frustrated worthlessness that I failed at that one thing I wanted. My heart perpetually had a book-shaped hole in it. I still loved to write; it still made me come alive. But each query rejection pushed me closer toward a feeling of obsolescence. Some nights my chest ached so bad that I actually couldn’t sleep; I cried once. I began to believe that only getting published would bring me lasting worth—even when a host of other things were, in reality, equal or surpassing in worth. Things like my actual job. Things like loving and investing in my wife and daughter. Things like helping the poor and sick in my community. Things that have lasting significance. Somehow, along the way, getting published went from a goal to a preeminent love. It consumed me. And while I still loved my story, trying to get it out into the world often made me kind of miserable.

Then I crossed over.

2) I’m getting published—but the shimmer has already begun to fade. I still wake up giddy that my dream has come true; but each time I do, the giddiness lessens. It’s not unlike staring into my closet each morning at that pair of shoes. When I bought them last year they actually made me feel like a better person; now they bore me. I’ve actually been thinking about going shopping. OK, fine—so I’ll just write another book. For a while it will feel good again—more heaping praise from friends and Twitter. But I know I’ll crave more. Maybe I write again and again and again; but the hunger will creep back. The joy I once had will turn out to be only circumstantial happiness more fleeting than morning dew. Like the first scenario, I’ll find less satisfaction in things that actually matter because what I’ve built my life around has not done what I hoped it would: fulfill me completely and indefinitely. I’ll have exactly what I wanted, but it won't be enough. Quite surprisingly, I might still be kind of miserable.

This all sounds depressing; but it’s actually incredibly freeing. See, if I lower this pursuit of getting (or being) published to its proper place in my life, relief floods in. Why? Because I’m no longer exceeding the weight limit that the thing was meant to have. Let’s say I never got published. Yes, I would be incredibly bummed (exuberant people get very, very bummed—ask anyone who knows me). But after all the bumming, I’d realize that it didn’t really matter as much as I thought. I’d see a book for what it was: a book. I’d also be spared the illusion that getting published would make me eternally happy—and the ensuing emptiness when it doesn’t. And if I do get published, I’m not fooled by the shimmer. I’ll still celebrate and revel and get super freaking excited—all things I’ve done since my book deal. But if guard my priorities, I won’t grow hollow when the excitement wears off—which it will. Arguably, I’ll enjoy it more because I see it for what it is: something really, intensely cool—a serious accomplishment. But something temporary. Something fleeting.

I struggle with this every single day; some days every moment. The stirring in my chest—once angst from the not yet and now joy from the finally—echoes an ongoing battle for supremacy. Writing has always wanted to be preeminent, and when I let it, it actually robbed me of some serious joy. I missed out on a lot of incredible moments and opportunities over the last couple of years because I was either tucked away writing or lost in my mind bemoaning my perceived writing failures. To believe that getting published would result in a different outcome flies in the face of what I know to be true about my own heart. However counterintuitive, I’m convinced that the more I build my life around writing—regardless of success—the more miserable I could very well become.

But the thing is, I can’t stop writing. Like exuberance, it’s part of me. It makes me feel alive. So what now?

What nothing. I keep writing. I just don’t let it take over.

Which is easier said than done.

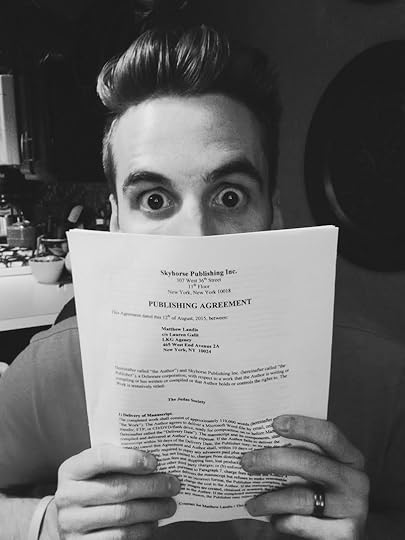

That Time I Got A Book Deal

Apparently the relentless, soul-crushing pursuit of something can end in sweet, sweet vindication that (almost) makes up for the nights spent wondering: Is this going to actually ever happen?

For me it happened last week when I signed a book deal with Skyhorse Publishing. Their children’s imprint, Sky Pony Press, will be publishing my debut YA novel in the Spring of 2017.

But it started way before that. When? I’m not really sure when I inceptioned myself that being a writer is what I wanted. Early, I think—maybe way earlier than I actually can pinpoint. Who knows these things. I can say more accurately that my first attempt at writing a book was eight years ago during student teaching. It was an awful, embarrassing attempt. Wincingly bad. More false attempts followed because that’s one thing I’m really good at: getting really excited about writing a book and then giving up after 3,000 words. I never planned or plotted or got feedback. I just kept it all to myself and did a bunch of really crappy writing. I was my own worst enemy.

An M.A. in History at Villanova changed that, exactly how you’d assume: my professors completely shredded my writing. They Marine Corps Boot Camp Drill Sergeanted me. I was bushwhacked. If it was a movie, it would be rated R for extreme and gruesome violence. I went into that program thinking I knew history and how to write; I quickly realized that I didn’t know history and that I had a serious crap-ton to learn about good academic writing. That was hard. As someone patently insecure, I struggled taking criticism. I didn’t get defensive, but instead convulsed with unnecessary panic. I worried that I’d made the wrong choice to start the program and that I couldn’t get the grades needed in order for my school to partially reimburse me. Around that time my wife reminded me that I live in habitual hyperboles. She told me to relax. Things got better.

Toward the end of that program—Fall 2012 I think—the idea for this particular book settled in my mind: a young adult thriller laced with Revolutionary history, but completely modernized. By now I’d honed my writing to a not-awful level and felt really good that a graduate journal had published one of my papers. But I wanted more. Yeah, there’s notoriety from other history nerds, and yeah, my professors were proud; that meant a lot, and I beamed under their condoning nods. But I wanted to write something that was going to be read outside academia—something, that in my mind, actually mattered to me and my eighth graders. In one of the few decipherable lines of Moby Dick, Melville surmised my angst best: “To produce a mighty book, you must choose a mighty theme.”

My mighty theme sprang from a deep well fed by two underground rivers: a father’s unwavering love for his son, and the concept of inherited treachery—being branded by the actions of one’s ancestor. While writing a paper on Revolutionary traitors that fall, this all sort of swirled together in my head and a question surfaced: where are the descendants of the Revolutionary generation today? Like, what’s Washington’s great-great-great-great whatever doing in 2015? Wouldn’t it be cool if there was a secret club of Revolutionary descendants today bonding over their ancestor’s mutual awesomeness? But there was a better question still submerged, way farther down that grabbed at my ankles: what about the traitors of the Revolution? Where are they? If Washington’s offspring are living the dream, then what about Benedict Arnold’s? And wouldn’t it be cool if the the descendants of the heroes still actively persecuted the offspring of the traitors out of some misguided sense of honor...?

And The Judas Society was born.

The journey from idea to draft to querying agents to rejections to more rejections was painful. So painful. A few highs, mostly crushing lows. And it all would have ended if not for my wife, whose constant support pushed me to keep writing and sending out queries—reassuring me that “someone will want this”. She counseled against my knee-jerk and ultimately foolhardy decision to self-publish just because I wasn’t happy with the current circumstance. And she was right. Ejecting from the cockpit and hoping the poorly packed parachute would save me wasn’t the right move; I just needed to get serious about flying the plane and figure out how to pull this thing out of the dive.

Most critically, she kept me grounded (yes, this goes against the previous plane metaphor, just deal with it). She reminded me of a salient truth that I struggle with constantly: to make this pursuit ultimate—to give it a preeminent place in my heart above God, my wife, my daughter, above my community that I’m called to love and invest in—was dangerous. It would twist me, distort me, command my emotions and time and mental space in nefarious ways. In this she echoed Pulitzer-Prize winner Ernest Becker (yes, I just dropped a random, esoteric 1970′s cultural anthropologist on you) in The Denial of Death: if I found my “cosmic significance” in this book, I would deify it—problematic because it was never meant to bear the “burden of godhood”. Even if my dream of being published came true, it wouldn’t be enough. Pursue it, she counseled, but don’t make it more than it is. It’s just a book.

You can see how I married up.

Fall 2014 things started to happen. Several agents expressed interest in the book, but the one who shared my vision wanted to see some edits before making an offer to represent it—wanted to see if I could maneuver out of some pretty tricky plot holes. It was a two-way job interview of sorts; I had to buy into her changes for the work, and she had to buy into my cleverness to actually make those changes happen. We both passed. The day before Thanksgiving, Lauren Galit of LKG officially offered to represent me. It was the hardest benchmark in my writing journey to reach, and the most critical.

See, to get traditionally published today, you need an agent because publishers don't (or rarely ever) accept unsolicited manuscripts from unagented authors—see also: me. Agents know the market; specifically, they know what editors are acquiring and what they’re sick of. In exchange for a small percentage of future profit, they agree—after deciding they like you and your book and that it has a chance of selling—to represent you. Think of them as very picky trail guides who only agree to take the people they think can make it to the goldfields of California. (This is a historical reference, you see.) They don’t promise you success, just the chance of it; in exchange you give them some of the gold you find. Sure, you can go on your own, but most likely you’ll die of bear mauling or starvation or cholera (all of which can serve as metaphors for various types of nontraditional publishing). They act as editor, encourager, hard-truth sayer, and above all, champion of your work. A good agent has your back, but isn’t afraid to say things to your face. They also apparently live on their email.

Lauren’s edits, in conjunction with LKG’s associate agent and stellar Middle Grade author, Caitlen, were fantastic. She zeroed in on problems I overlooked, sniffed out narrative miscues, and thus pushed the book to an entirely new level. Edits were too numerous to count; think in the hundreds. It was both thrilling and excruciating. I was finally working with legit book people. I also most definitely sank near or into depression (habitual hyperboles, again). But the thing is, it’s what I needed. It’s what my book needed.

May 2015 brought the awful, three-month wasteland of waiting known as “submission” where Lauren sent out the manuscript to interested publishers she’d previously hooked with a pitch. If you listen very carefully, you can still hear the deafening silence of that waiting. A rejection or two would trickle in with feedback ranging from good to oddly vague. More waiting. An editor would leave a press, and we’d have to find another one there. More waiting. A rejection with feedback that stung. More waiting. A tug on the line: an editor saying she’s halfway through and loving it. More waiting. Depression. Anxiety.

Waiting.

And then Lauren’s email: “The publisher wants to set up a phone call.”

The rest is not always downhill for all authors, but thankfully it was for me. Phone call with editor Alison Weiss at Sky Pony went fantastic; book was passed up the chain; book was approved. Offer was made; offer was accepted. Contracts were haggled over; contracts were signed. Author took selfie with contract. Agent submitted deal announcement to Publisher’s Weekly.

Author screamed for joyous relief.

Silver linings run through this journey. The difficulty of channeling my passion into this book yet not making it preeminent is for sure at the forefront. Another is that I’m not deluded—a latent fear always lurking in the back of my mind. That is to say, my ideas, prose, and ability to execute an idea can actually produce something desirable by people who publish books. My wife has always told me that I can write, and that my ideas were good. I believed her, but it was a hard thing to do. I am quick to self doubt by nature, preferring to think less of myself because it’s much safer. If I go into it saying “just a heads up: this isn’t that good”, then I won't feel the crushing disappointment if others don’t like my work. It’s a problem. Therapy is helping.

The bitter sweet part of all this is that I’ll be giving up my teaching job. JK; I’d never do that. I need inspiration from my amazing students and faculty, not to mention the money. Not that this was ever about money—though to be clear writing is probably the worst way to make money, ever. Yes, money is good. I like money. I’d like more of it. But what I really wanted was a major league creative marketplace. I wanted someone—despite the subjectivity that governs life and the book business—to say, “We like your writing. We want others to read it. Come write for us. Join our team.”

Last week I joined the team at Sky Pony Press. There is no figure of speech to accurately communicate my state of happiness. My emotions transcend hyperbole. And yeah, there’s a ton more work ahead, and a publication date of Spring 2017 that feels like thirty years from now, but that’s fine because this adventure has been wild and this summer epic. I’ll never forget it.

That time I got a book deal.

Winning July 4th

My town holds an annual July 4th Baby Parade. The crowned jewel of categories is “Most Patriotic”. We, and America, won.