Matt Rees's Blog - Posts Tagged "novels"

Krimis, polars, gialli: what crime novels are called around the world

Sometimes people talk about crime novels as though they were all the same. The sheer number of different names for variants of the crime novel proves that isn’t true.

Police procedural. Mystery novel. Thriller. Cosy. Exotic detective. Supernatural. I used to think there was little real difference, but then my UK publisher told me he wanted to change the title of my first novel “The Collaborator of Bethlehem.” He thought it sounded like a thriller (which men typically buy) and he wanted it to be clear that it was a mystery (so that women would buy it.) He changed the title in Britain to “The Bethlehem Murders.” I had to acknowledge that he was right: it sounds more like a mystery, doesn’t it.

And that’s only in English.

As I travel around to promote my books in different countries (I’m published in 22 countries these days), I’ve noticed that there are interesting variations on the names we use in English for crime novels. Some of them are quite entertaining, and some of them tell us something revealing about how the genre developed in that country.

Take Italy. Mystery novels there are called “gialli,” or yellows. That’s because traditionally the genre was published with a yellow cover. Even today the mystery shelves of Italian bookshops are largely yellow.

Color is the theme also in Spain, where crime novels are “novelas negras,” black novels. According to a source of mine on the literary desk of El Pais, the big Spanish newspaper, this harks back to the old “Serie noire” of French publisher Gallimard. That series introduced the crime novel to Spain. So noir, or black, became the identifying color for a crime novel.

A “roman noir,” black novel, is also one of the ways of referring to a crime novel in France, because of that Gallimard series. But the most common slang for a mystery in French is “un polar.” It’s a contraction of “roman policier,” police novel, and was first recorded in 1968. If you ask most French people to explain the origin of the word “polar,” they can’t tell you: the abbreviation has become so common, they’ve forgotten its rather simple derivation.

Germany (as well as the Scandinavian countries) calls a crime novel “ein Krimi,” short for the word Kriminelle, criminal. No surprise there. It’s a catch-all for thrillers and detective stories of all kinds.

There is, however, an amusing sub-genre in German. In English, the “cosy” refers to Miss Marple-type novels in which the detective is an amateur, usually a lady (not just a woman), probably an inhabitant of a quaint village, investigating a murder in a country house or a vicarage.

The Germans call these cosies “Häkel-Krimis“. Miriam Froitzheim, who works at my German publisher C.H. Beck Verlag in Munich, translates this as “Crochet Crime Novels.” Because, as she puts it, the detective “puts her crochet gear away to solve the murder.”

I’ll keep scouting for interesting ways of describing crime novels around the world. But if you know of some others, tell me about them.

Police procedural. Mystery novel. Thriller. Cosy. Exotic detective. Supernatural. I used to think there was little real difference, but then my UK publisher told me he wanted to change the title of my first novel “The Collaborator of Bethlehem.” He thought it sounded like a thriller (which men typically buy) and he wanted it to be clear that it was a mystery (so that women would buy it.) He changed the title in Britain to “The Bethlehem Murders.” I had to acknowledge that he was right: it sounds more like a mystery, doesn’t it.

And that’s only in English.

As I travel around to promote my books in different countries (I’m published in 22 countries these days), I’ve noticed that there are interesting variations on the names we use in English for crime novels. Some of them are quite entertaining, and some of them tell us something revealing about how the genre developed in that country.

Take Italy. Mystery novels there are called “gialli,” or yellows. That’s because traditionally the genre was published with a yellow cover. Even today the mystery shelves of Italian bookshops are largely yellow.

Color is the theme also in Spain, where crime novels are “novelas negras,” black novels. According to a source of mine on the literary desk of El Pais, the big Spanish newspaper, this harks back to the old “Serie noire” of French publisher Gallimard. That series introduced the crime novel to Spain. So noir, or black, became the identifying color for a crime novel.

A “roman noir,” black novel, is also one of the ways of referring to a crime novel in France, because of that Gallimard series. But the most common slang for a mystery in French is “un polar.” It’s a contraction of “roman policier,” police novel, and was first recorded in 1968. If you ask most French people to explain the origin of the word “polar,” they can’t tell you: the abbreviation has become so common, they’ve forgotten its rather simple derivation.

Germany (as well as the Scandinavian countries) calls a crime novel “ein Krimi,” short for the word Kriminelle, criminal. No surprise there. It’s a catch-all for thrillers and detective stories of all kinds.

There is, however, an amusing sub-genre in German. In English, the “cosy” refers to Miss Marple-type novels in which the detective is an amateur, usually a lady (not just a woman), probably an inhabitant of a quaint village, investigating a murder in a country house or a vicarage.

The Germans call these cosies “Häkel-Krimis“. Miriam Froitzheim, who works at my German publisher C.H. Beck Verlag in Munich, translates this as “Crochet Crime Novels.” Because, as she puts it, the detective “puts her crochet gear away to solve the murder.”

I’ll keep scouting for interesting ways of describing crime novels around the world. But if you know of some others, tell me about them.

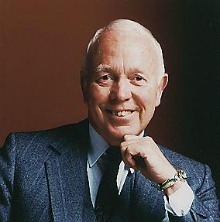

The Writing Life: Warwick Collins

The riskiest thing for a writer to do is to try to enter the head of a great genius by making that genius the narrator of a novel. Why? Because if you aren’t a genius of at least similar proportions, it won’t ring true. Think of the tedious melodrama that passed for the life of Michelangelo in “The Agony and the Ecstasy”. When that genius is the greatest writer of all time, the risk to our present writer increases proportionally. Warwick Collins, a British novelist and poet, took that chance when he made William Shakespeare the narrator of his novel The Sonnets. But it was worth it, because Warwick succeeded and The Sonnets is by far the most beautiful novel of recent years. It’s also an astonishing examination of why a writer writes and of how a literary work can change along with the life and loves of the writer. That makes Warwick the perfect author to answer the questions posed here in The Writing Life. He has some surprising ideas.

How long did it take you to get published?

I was fortunate that my first book, a sailing thriller called Challenge, was bid for by eight publishers. It was eventually published by Pan/Macmillan

Would you recommend any books on writing?

I don’t know any books on writing that I would recommend. The best way to learn about writing, I suspect, is to read as much good literature as one can.

What’s a typical writing day?

I’m one of those annoying people who feel fresh when they wake up, so I try to put in a minimum of one and a half hours before breakfast. If I feel up to it, I’ll return at various stages in the day. But I find writing is quite a nervous and energy-sapping process, and often I find that after my morning efforts I need the rest of the day to recover and be ready for the next early morning attempt on the blank screen.

Plug your latest book. What’s it about? Why’s it so great?

My most recent novel The Sonnets is an attempt to describe Shakespeare’s life from 1592-4, the years in which the London theatres were closed by threat of plague, and the 29-year-old Shakespeare was forced back on his own resources. He was fortunate to find a patron in the young Earl of Southampton. Those were the years in which many of the other playwrights died of violence (like Marlowe, killed in suspicious circumstances in a pub or Kyd, put on the rack) or of poverty, like Greene. Shakespeare emerged from those turbulent times to become the leading playwright on the Elizabethan stage. During those plague years, too, it is widely believed that Shakespeare wrote the bulk of his great sonnet sequence. I’ve integrated 32 full length sonnets into the text of my novel. I also added two “imitation” sonnets – both carefully flagged up as imitations, by the way. It was fascinating attempting to compose those imitation sonnets, and I think it helped me to gain an insight into the way sonnets are constructed, and how the very tightly defined form imposes on the content.

How much of what you do is formula dictated by the genre within which you write, and how much is as close to complete originality as it’s possible to get each time?

So far I’ve always been criticized by UK and American corporate publishers for NOT writing to a formula and for constantly changing both the subject matter and the style with which it is approached.

Who’s the greatest stylist currently writing?

For prose, Cormac McCarthy; for dialogue, Elmore Leonard.

Who’s the greatest plotter currently writing?

Philip Pullman, for His Dark Materials trilogy.

How much research is involved in each of your books?

I thoroughly recommend writing the first draft of the book before one does detailed research. This appears the wrong way round, but I believe it is still vastly more effective. Knowing the subject matter of the novel greatly narrows the research area, and the result is that the research in that area can be highly focused and detailed. The Rationalist and The Marriage of Souls were both set in the eighteenth century, about which I knew very little. I could have spent years reading up about the eighteenth century and only used a fraction of my laboriously acquired knowledge in the novels. But, for example, once I knew that Silas Grange, the protagonist, was a physician of “modern” outlook (for the times), I could research the area of medical practice in far greater depth than otherwise would have been the case, and virtually all of it was useful.

Where’d you get the idea for your main character?

A number of writers I have talked with are inspired by people whom they’ve met. In my own case, I get interested in an idea first, and after that it’s more a matter of trying to build up a character from the circumstances. In the case of The Rationalist, for example, some of the few things I did know about the eighteenth century were that it was a time of loss of religious faith, of the rise of science, and the loosening of sexual mores – in that way a reflection of our own times. It seemed interesting to me if Grange had elements of a modern scientist in his character, was perhaps a touch obsessive, pragmatic, rational, thorough, and if the femme fatale who brought him down, Mrs Celia Quill, was something of a proto-feminist.

What’s your experience with being translated?

So far pretty good. I’ve been fortunate that my foreign language publishers have chosen good translators.

Do you live entirely off your writing? How many books did you write before could make a living at it?

I have lived mostly off my writing for about 20 years, but I’m unusual in that most of my income has come from foreign language translation/publication, and from occasional forays into screenwriting.

How many books did you write before you were published?

My first published work was a series of poems published in the magazine Encounter. I wrote two novels before Challenge was published. They both seem to me now to be somewhat juvenile, and I would have no interest in either of them being published.

What’s the strangest thing that happened to you on a book tour?

During a tour of Germany for the German edition of my novel Gents, my publisher was based in Munich. Gents is a novel about three immigrant West Indians who run a urinal in London, and spend much time trying to suppress the “cottaging” (sexual activity between men) which goes on in the cubicles. Each of the West Indian main characters is religious and something of a family man, too, so this background activity is somewhat shocking to them. Although I am not gay myself, Gents was fortunate to receive favorable reviews from the gay press, and from West Indian reviewers. I don’t know whether my German publisher, a leading feminist, was being mischievous, but while on book tour she booked me in at a famous gay hotel in Munich. That was a very interesting experience.

What’s your weirdest idea for a book you’ll never get to publish?

The weirdest idea I have had for a book was Gents, and I did publish it, and am glad that I did.

Toronto Star: Palestinian crime novels the key to happiness

Toronto Star Mideast correspondent Oakland Ross writes about my path to happiness -- via the less than happy occurrences of the region. It's a different, more personal kind of profile than the sort of thing journalists usually write, which is perhaps due to the novelist's sensibility Oakland brings to the piece (He's the author of historical novels set in Mexico.)

Welsh writer quit Time magazine to pen books in popular sleuth series

May 27, 2009 Oakland Ross MIDDLE EAST BUREAU

JERUSALEM–Happiness did not find Matt Beynon Rees.

Instead, Matt Beynon Rees found happiness.

First, however, he was obliged to travel to the Middle East, not a region of the world noted for an over-abundance of glee. Read more...

Welsh writer quit Time magazine to pen books in popular sleuth series

May 27, 2009 Oakland Ross MIDDLE EAST BUREAU

JERUSALEM–Happiness did not find Matt Beynon Rees.

Instead, Matt Beynon Rees found happiness.

First, however, he was obliged to travel to the Middle East, not a region of the world noted for an over-abundance of glee. Read more...

Stealing the novel

If there’s one thing that authoring a series of novels will teach you, it’s that you can’t wait for inspiration. But you can prompt it, give it little electric shocks that’ll keep it bubbling within you. Here are a few methods I use to do that.

If there’s one thing that authoring a series of novels will teach you, it’s that you can’t wait for inspiration. But you can prompt it, give it little electric shocks that’ll keep it bubbling within you. Here are a few methods I use to do that.I go to the places I’m writing about. I talk to people who might be similar to (or even the basis for) my characters. I read about them and their world. I engage in the same activities in which they specialize. But I also read about entirely different subjects – so long as they’re extremely well-written.

Some of these ideas sound self-evident. I’ve written a series of Palestinian crime novels, so it stands to reason that I’ve spent the last decade and a half in Gaza, Bethlehem, Nablus, Jerusalem, tasting and smelling and talking and looking. I even force myself to read the drivel that gets written about this place in journalism and nonfiction—occasionally I come across something good, but mainly it just gets me down. How many times can you listen to a mediocre pop song? Well, that’s how most Middle East journalism sounds in my ear.

For a novel I have coming out next year about Mozart, I learned to play the piano. I learned that I wasn’t much good at it, but I also saw inside the music in a way I couldn’t have done merely by listening.

Not so obvious, however, might be the wide reading. A number of writers I’ve met or read about say they don’t have time to read anything that isn’t directly related to their research. In other words, if I’m writing about Berlin, it’s goodbye to Raymond Chandler for the next 12 months.

Well, T.S. Eliot wrote that “Immature poets imitate; mature poets steal.” I can look back at my literary efforts as an undergraduate and see what imitation there was throughout all of it. Now I’m mature (I try to fight it; I work out; but I concede, I’m maturing…) and I’ve figured out how to steal.

What Eliot meant was that it takes a while, as a writer, to realize how to make things your own. That means going beyond the plagiaristic imitation of youth, which is humble and filled with homage, to the confident sense that whatever you see another writer do, you can do it better. Then when you read something good, it doesn’t appear in your work as the same thing—it spurs you to develop your own spin on the thought that’s provoked in you by what you’ve read.

Let me give you an example. I challenge any one of you to show me a contemporary writer who can build a character in a fuller, more convincing manner than Hilary Mantel, who won the Booker Prize last year for her masterful “Wolf Hall.” If anything, her 1992 classic “A place of Greater Safety,” a novel about the French Revolution, is even more amazing than her now-famous prize-winner.

“Greater Safety” tells the story of the entire revolution through the characters of Robespierre, Danton and Desmoulins. From their childhoods to (it’s a historical novel so I don’t have to give any spoiler alerts) their executions. Each of them is built slowly, and we see their character arc in a way that even they don’t—watch their idealism tainted with violence, until it turns on them. Because we take that journey with them, we care more deeply for them, even as they become murderous and unjust.

The “stealing” comes in whenever I see a point that Mantel uses to build that empathy. Robespierre, we learn, always carries a tiny copy of Rousseau in his pocket. Some time later it’s on his desk and Desmoulins notices it. Just one sentence. A couple hundred pages later someone quotes Rousseau against him and only his close friends understand that he’s entirely defeated. We know he’s a man who has bent principles for his friend Desmoulins, but he can’t desert them completely. It’s a choice between Desmoulins, whom he loves, or the book that he keeps close to his heart. Books always win in contests like that.

That doesn’t make me want to replicate the exact same thing in my next book – that’s what I might’ve tried when I was 19. Instead, I think of ways in which to send a signal to the reader. To plant an object that inspires a character, that takes them on the path on which we follow them in the novel. Until ultimately it underlies their collision with another character; makes compromise an impossible undermining of everything they believe about themselves.

That’s stealing, and it’s a good thing to do.

You can find such moments in the small factoids of history books, if you’re researching a period, or in nonfiction. It’s in poems, where a phrase about a frieze on an urn (“Thou still unravished bride of quietness”) will spark a thought about your memories of your own wedding or of a sexual exploit which you can use for a character in your book.

A writer whose obvious focus is character would be the most direct place to start. In other words, not the kind of ultra-bland snoozing that appears in the short fiction of The New Yorker, which always seems to be written as though it were designed to mimic a relatively dull person telling you a story in a cocktail party or at the counter of a bodega.

Choose something with sweep, like Mantel. Someone with an eye for a mordant detail, like Graham Greene in “The Honorary Consul.” Someone who shows you an entire, devastated culture through the eyes of one man, like Martin Cruz Smith’s investigator Arkady Renko.

A novel’s like a marathon. Stop and sit down at the side of the road and no amount of sprinting will get you to the finish line. You have to write every day and once you’re started you can’t stop. “Stealing” is a way of warming up for the long run.

Published on April 15, 2010 00:12

•

Tags:

a-place-of-greater-safety, berlin, bethlehem, booker-prize, crime-fiction, danton, desmoulins, gaza, graham-greene, hilary-mantel, historical-fiction, israel, jerusalem, martin-cruz-smith, middle-east, mozart, nablus, novels, palestine, raymond-chandler, robespierre, t-s-eliot, wolf-hall, writing

Meditating the next novel

I’ve written here in the past about how I use meditation techniques to get into the zone for writing every day. But now meditation seems to have helped me come up with the idea for my next novel.

I’ve written here in the past about how I use meditation techniques to get into the zone for writing every day. But now meditation seems to have helped me come up with the idea for my next novel.Last week I was in a rotten mood. My son woke up too early. I hadn’t slept well. The boy was whiny and tossing his Cocoa Crispies on the floor. The crema on my espresso was too thin. Oh, blah blah blah. I packed Cai off to kindergarten and lay down to meditate, as I do before I begin work every day (I used to meditate after I finished work, but I often just fell asleep, so now I do it earlier).

I focused on creativity and positivity as I meditated. I started to get ideas about… well, I’m not going to tell you what the novel’s about before I write it. Let’s just say the idea of happiness and brain function – the very things behind successful meditation – led me into a historical thriller plot that I will start researching as soon as my current project, a novel about the Italian artist Caravaggio, is completed.

What neuroscience tells us about meditation (and any neuroscientist – she knows who I mean – reading this ought to refrain from writing comments about how dumb I’ve made this sound) is that positivity rewires the brain to be yet more positive. My meditation in question proves that in a small way. I was far from positive until I began the meditation. Suddenly I was as positive as I can be – coming up with a new novel isn’t something that happens every day.

Well, actually it does happen quite frequently (for example, just now I’m thinking, “What about a mystery novel set in the Swinging Sixties in which Benny Hill is the detective”…). But those ideas don’t carry the same element of certainty that this would be the novel for me to write. I had been juggling at least five ideas for my next book. None of them had struck me as absolutely right on a deep level. Dare I say it in these cynical times, on a spiritual level. They all had something logically right about them, but they didn’t feel right.

To an extent, I owe this idea of positivity to some recent chats with Tony Buzan, author of The Mind Map Book and other volumes. We spent time together at a recent book festival in Dubai. Tony’s main point is that we only use a tiny fraction of our brain’s capacity. About 1 percent. His work is designed to enable us to increase that percentage.

Read the rest of this post on my blog The Man of Twists and Turns.

Published on April 07, 2011 00:24

•

Tags:

benny-hill, caravaggio, meditation, mind-maps, novels, tony-buzan, writing