Judy Lynn Johnson's Blog

May 12, 2014

Talking About Baseball

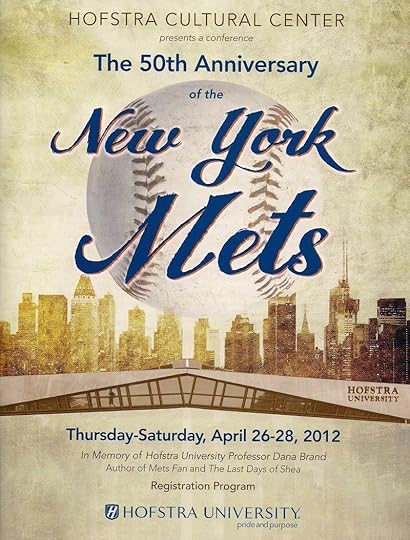

Last Thursday morning, I had the great pleasure of introducing Watching the Game on podcast radio during a conversation with Ron Kaplan, the host over at Baseball Bookshelf. Ron and I met two years ago at Hofstra University during the 50th Anniversary Conference of the New York Mets. He is the author of 501 Baseball Books Fans Must Read Before They Die (University of Nebraska Press, 2013).

I love a good baseball conversation, and I thoroughly enjoyed answering the intelligent questions that Ron asked during the 30-minute interview. I hope you enjoy it, too!

To hear more about Watching the Game: A Baseball Memoir, please go to:

Ron Kaplan's Baseball Bookshelf

cheers and thanks!

May 8, 2014

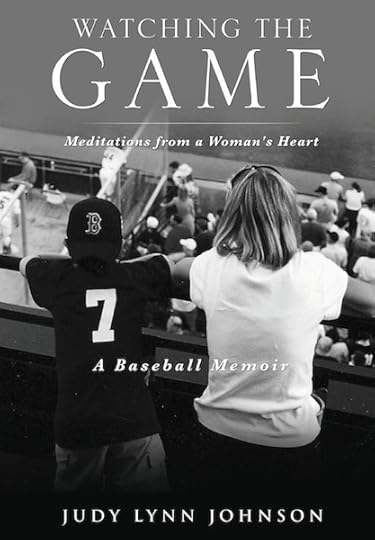

Book Release: Watching the Game

"Language has a way of lasting when the game is over."

Finally, here it is, friends and family - my modest and very personal attempt to give something back to the game that I have loved for most of my life. Once a blog, now a book, Watching the Game: A Baseball Memoir is available in paperback and hardcover at Amazon.com.

Many thanks to my beloved family, and to all the wonderful friends and colleagues who have been part of this journey. I am pleased to share the complete story with you and with anyone else who happens to find this memoir along the way.

available in hardcover and paperback at amazon.com

available in hardcover and paperback at amazon.com

May 3, 2012

Literature, the New York Mets, and the Tug of Baseball

A paper presented at The 50th Anniversary of the New York Mets

Hofstra University ~ April 28, 2012

________

Judy Johnson, Hall of Fame, 1975.

“Sure-handed third baseman from the sandlots of Delaware. A key player in the Negro Leagues. Good instinctive base-runner . . . line drive hitter with an excellent batting eye; a smart, soft-spoken and well-respected player, an athlete whose intelligence set him apart."

If I were a professional ballplayer, these are attributes I'd hope to display. William Julius Johnson. Judy. What an honor to bear his name.

But I’m not that Judy Johnson. I’m an English teacher, ordinary fan, mother of three children who love baseball. One of those kids slept peacefully in my arms on a long escalator ride to the top of Candlestick Park in August 1986. My firstborn son was six weeks old, and I had to show him the game, and the visiting team. I had to show him my Mets.

Three summers later we sat in 95-degree heat, 8 rows from the tippy top of Shea Stadium, all sticky with Dove Bar and beer. My boy was with me on the night that Number 8 kept Game 6 alive. When it was all over, I jumped up and down on the bed - “They won! The Mets won!” - and twirled my baby around the room, screaming, “I can’t believe they won!”

A few months later that tiny child spoke one of his first words: Mookie.

I cannot boast vast quantities of baseball knowledge or memorabilia, but a few Mets items have taken up residence in my home: a plastic chip-and-dip plate in the shape of a baseball glove molded in orange and royal blue. A 3x3 black-and-white photo of Ron Hunt, snapped on April 12, 1965. He’s walking back to the dugout on a dreary opening day. Few fans are in the seats at Shea. We’re two hours early, Dad and I, and my sisters, ages 5 and 7.

On my writing desk, a ball signed by Tom Seaver, another by Ed Kranepool, together with an 8x11 portrait of Cleon Jones, his arms outstretched, body leaning forward, knees slightly bent, eyes looking up, hands coming together – and his graceful signature in bright blue permanent ink.

I own an exquisite library full of books - classical, English, American, postcolonial; Dante, Chaucer, Spenser, Shakespeare; the OED complete 13-volume set, precious editions of Austen and Woolf, a slim folio signed by T.S. Eliot. Prodigious intellects lend gravitas to my collection: the Jameses, both Henry and Bill, plus those of a different order: Kiner’s Corner; Straw; The Bad Guys Won; Wherever I Wind Up; The Complete Game, by Ron Darling; Great Moments in Baseball, by Tom Seaver, Miracle Man, Nolan Ryan; Ya Gotta Believe! and 100 Things Mets Fans Should Know and Do Before They Die.

I like the fact that John Donne keeps Tug McGraw company on my shelf. I need the words of baseball. I feel this as an intellectual and spiritual need, romantic and physical.

I’ve followed the New York Mets for 50 years. How can this possibly be? How can I be older than a ball club? I’ve endured longer than Shea Stadium did (by a decade), a fact that saddens and amuses me . . . .

Rooting for the Mets as a child in the 1960s was a perfect way of preparing for life’s and baseball’s disappointments, failures, losses, and dysfunctions. Long before I heard the cliché, I understood viscerally that baseball is a game of failure, because I lived that truth with the early Mets. They taught us not to set the bar too high, until along came an expertly coached team of men who showed us the difference between mediocrity and grandeur. I rooted for the Mets because they were my dad’s team. Their abysmal debut season 40-120 felt like a huge win to me, because I’d discovered an amazing game at the tender age of 7 and delighted in every part of it.

Baseball didn’t begin with souvenirs, t-shirts, and a lot of food; it started with names, sounds, and rhythms in our home. It began with words.

My father was a Dutch Reformed minister who worked 7 days a week and many evenings too, but when he came home and spent time with me, baseball asserted itself as language, and this is how the game felt most real. My dad spoke two languages, scripture and baseball, his words rooted in love, with phrases that became deeply embedded in my young psyche: “3-2 count,” Love is patient and kind . . . “in the cellar,” my rock and my Redeemer . . . “6-4-3 double play,” and the Word was made flesh.

The game’s magical vocabulary - metaphor and idiom, syntax and rhythm, diction both poetical and crude – was the highlight of our daily conversation, a joyful mode of thought, a language that I loved. While learning to speak English in increasingly complex ways during my school years, the splendid lexicon of baseball was a key part of the curriculum, while the New York Mets felt like something basic and fundamental – as normal, natural, and necessary as speech itself.

Baseball is a physical thing, of course, and I loved the grit of it long before Title IX and Little League finally opened the gates to young women. I played ball with Tunis Van Peenen and Michael Minervini every day after school on the John F. Kennedy playground. Traveling across the monkey bars, I sang my song of the ’66 Mets, their names forming a happy litany: McMillan, Hunt, Luplow, Jones, Bressoud, Kranepool, Grote, Swoboda.

The Mets kept me company long after the real boys went home.

While my best friend Janet Vandergoot gloated about Mantle, Maris, Murcer and Ford, I defended Danny Napoleon and Choo Choo Coleman. Baseball began with the names of men chanted on the playground, sung in the kitchen, playing on the radio out on the screened porch on summer nights, and read in the quiet of my closet while I studied many slim pieces of cardboard.

The beginning of baseball was the word: Edward Emil Kranepool. 6’ 3.” 205 lbs. Bats: L. Throws: L. Bronx, NY.

My eyes traveled slowly from one horizontal line to the next until a few diminutive letters stopped my breathing, and changed my life . . . .

To read the complete paper, please download here:

Literature, the NY Mets, and the Tug of Baseball

April 24, 2012

50th Anniversary

__________________

It will be my great pleasure to present a paper at the 50th Anniversary of the New York Mets conference, in memory of Professor Dana Brand:

"Literature, the New York Mets, and the Tug of Baseball"

Session: The Writer's Game

Saturday, April 28

1:30 - 3:00 p.m.

What an honor and thrill it will be to meet some legendary Mets players, connect baseball and literature, gather with other fans, and pay tribute to the team I have loved since I was 7 years old.

To download the complete program, please click here:

More to come next week!

February 27, 2012

The Greatest Show

"There are more people out there touring the nation . . . chasing the purity offered by minor league baseball than you'd think."

- James Bailey

In his debut novel, The Greatest Show on Dirt, James Bailey does our national pastime a genuine service by bringing to life a few random members of a Durham, North Carolina ballpark staff and its groundskeeping crew, those undervalued individuals whose gritty actions on the field and dubious antics behind the scenes are paradoxically essential to maintaining baseball's illusion of purity and beauty. The field. Isn't it the field, after all, that matters most to players and fans? The pristine ballpark inspires athletes to begin anew each day - whether they are Bulls or Lugnuts or Yankees, while spectators welcome the sight of a beloved landscape that is both familiar and brand new.

Yet seldom do we think about those who tend to baseball's stunning canvases of lawn and dirt as anything but props or one-dimensional figures, anonymous men and women in khaki and sneakers who run quickly in a sudden rain delay or appear predictably during the seventh-inning stretch.

You might stop me here, because maybe you love to arrive at the field early, as I do, just to see the grounds crew raking and tamping the ground, spraying a hose, painting the lines, readying the field, and making it new. Maybe there is something wrong with me, but the very sight of a John Deere idling in the infield or moving in gentle circles in the distant grass gets me excited.

That guy on the tractor, that woman with the rake, those four men holding a hose just right, the kid with the paint - they live real lives. Their territory is worth knowing, and James Bailey, who spent three seasons of his life with the Durham Bulls, invites us in. The Greatest Show pays tribute to the young men and women without whose efforts the show simply wouldn't happen as we know it. Cocky and talented ballplayers are present in Bailey's fictional account, but their stories become secondary to those of ordinary folk who have more modest yet equally poignant dreams of "climbing the minor league ladder."

Most true baseball fans understand that the game is anything but glamorous behind the scenes, except perhaps among the elite and chosen few. Bailey deals in the humble geography of the sport, not in its glitzy urban centers, nor in sleek stadiums that feel like corporate headquarters or a Disney set. If you've ever traveled to Frederick, Wilmington, Kinston, Savannah or Salem for the pure love of it, you know what I'm talking about.

Bailey's story gets off to a rather slow start as he seeks to define the mediocre existence of his first-person narrator, Lane Hamilton. Experiencing unsettling feelings of ambivalence in his personal life and intense frustration with his uninspiring middle-management career, Hamilton looks toward the ball field for meaning, if not material success. The plot takes a while to gather momentum, but the slow pace of Bailey's first few chapters, notwithstanding Hamilton's urgent desire to change his life, has the pleasant feel of a ballgame that begins quietly. Not too many fireworks, just an easy pace that gradually draws you in, maybe with a bit more in the way of routine defense than kinetic offense.

The score of this minor league game doesn't particularly matter, though, because the runs, hits, and errors in the yard take a back seat to its raw material. Game summaries, play by play, and live action on the field are not the novel's primary concern. Instead, these components play in counterpoint to something equally important. It is quite literally the dirt of this novel's title that provides some of the most satisfying action in Bailey's story: "See what happens when you run with it?" A fellow named Rich points to the ground: "You get those waves from the mat popping up and down." The novel's hero is learning ever so awkwardly the difficult technique of dragging the field.

Bailey adeptly dramatizes those essential actions of scene-making we often take for granted. The mesmerizing imagery of a tarp being pulled from the field, for example, becomes a matter of pride and a thing of beauty: "We'd had plenty of practice getting the cover on and off the field all week, but we'd also had at least five guys every time, which was a comfortable minimum for a dry tarp pull. Silently, we fanned out, each grabbing a portion of the edge, slowly trudging across the diamond as we folded the monstrous sheet in half . . . Back we walked to grab the crease and pull again, folding it into quarters this time. It got heavier with each pass, but the walk got shorter so it kind of evened out. When the tarp was folded in eighths, we pushed the twenty-five foot corrugated aluminum center pipe into place and began wrapping the plastic cover around it."

This may be more groundskeeping detail than the average fan ever wants to know, but such moments of competence gain importance in Bailey's narrative as a genuine labor of love. This author ventures into a territory that baseball writers seldom consider; he enters a realm of stats that most sabermetricians and ordinary fans don't usually factor into the equation:

"Frederick held on for a 14-11 victory in a contest that featured two grand slams, four hit batters, and nine stolen bases, including a swipe of home. But the most impressive statistic of the homestand was the nine tarp pulls, dating back to Wednesday. It wasn't a record, at least not according to Johnny Layne, who boasted his Gastonia crew had pulled the tarp thirteen times in a four-game series back in July of 1972."

Bailey has a fine ear for dialogue, and since much of baseball is conversation, the lively interplay of voices on and off the field is essential to the texture of his novel. Efficient game summaries move in counterpoint to amusing dialogue on the sidelines; conversations take place before, during, and after the games, and late into the night. Equally important are Lane Hamilton's private thoughts, particularly as he struggles to balance the satisfying freedom of baseball life with the increasingly unpleasant constraints of a relationship that offers little in the way of authentic love.

The plots of romance and sport inevitably converge, and the narrative takes its most appealing turn when one of Hamilton's co-workers voices a key concern about his very pretty yet distant girlfriend: "Why doesn't she come to the games?" The rhetorical question requires no answer, because an important truth has already been spoken.

The most significant relationship in Bailey's novel is not that of coach-player, pitcher-catcher, or athlete-fan. Instead, the story's energy resides in an unexpected connection between two co-workers who encounter each other in the midst of ordinary, seemingly tedious activity on the field:

"Hey, y'all," calls a female voice. "What do I do?"

"'Just what I do,' I yelled above the roar of the storm, as she lined up next to me, leaning into the roll.

The tarp came unrolled kind of wrinkled and crooked, on account of the shitty job we'd done that morning, and you had to watch your step or you could easily trip where it was bunched up."

Now, who cares about wrinkles in a tarp? I wondered, while reading.

Well, I do. I like a story that celebrates unsung heroes and hardworking folk. I like a story that puts a woman at the center of the field. I enjoy the symmetry and simplicity of a straightforward question and answer: What do I do? Just what I do.

The Greatest Show on Dirt came as a surprise to me. I expected more in the way of locker room jargon, raw humor, clubhouse antics, hits, errors, and food fights. These ingredients are all in place, to be sure, lending the novel its authenticity and some of its momentum. But the book surprised me, because it's not entirely what its inviting cover suggests - a gritty texture, an abandoned game ball, the amusing mascot, shabby splinters, peeling paint in colors of rust and faded blue. What I did not expect was a love story; what I did not expect was a candid account of what goes on in a man's heart during a minor league season. Deep down, beneath the dirt and grit, men can be such romantic souls.

Spoiler alert. What I did not expect was romance taking shape the old-fashioned way, affection growing slowly and sincerely over time, love becoming real even before the character realizes that's what it is, all this personal stuff happening unobtrusively amid tarps and hoses, as ordinary people groom the field for bigger egos and men with names on their shirts.

The Greatest Show on Dirt raises a question I sometimes think about in broader terms: do men really want women around to share the game with them? Yes, I think there are some who do. And if so, to what purpose, I wonder.

"Why doesn't she come to the games?" asks one of Lane's friends. Does it matter whether she is there or not? Maybe it does.

"What do I do?" she asks. "Just what I do," he says, yelling above the roar of the storm.

Does it matter? Maybe it does.

please click here to order

James Bailey, The Greatest Show on Dirt

February 17, 2012

Farewell

“And listen to the sound of a new beginning

Oh, this is where the old is ending

Listen to the sound . . . .”

We arrived at the ballpark early, my sister and I. Very early. Two weeks ahead of pitchers and catchers. Few people walked the neighborhood. No one rehabbing or laying down bunts on the practice fields. No vendors selling beer and popcorn in the stands.

It was early February and I couldn't wait to see a game. Any game. How blessed we were to see much more.

Roger Dean Stadium, Jupiter, Florida. When spring training begins, the Miami Marlins and World Champion St. Louis Cardinals will share this facility and its strikingly ordinary ballpark built with such comfortable, inviting human proportions in mind. Tonight belongs to a different team, however. It's the season opener for the NCAA Divison II and NCCAA Palm Beach Atlantic University Sailfish. Their coach: Gary Carter, onetime Expo and New York Met, winner of five Silver Slugger awards, three Gold Gloves, 11-time All Star, HoF inductee 2003, proud family man, dying tonight of brain cancer. A pitcher named Darling paid tribute to Carter on the MLB Network recently, holding a simple sign while remembering the strong, vibrant man who once squatted behind the plate.

We arrive to find a remarkably peaceful place. No noisy throngs of snowbirds hungrily seeking autographs of big-leaguers and future stars. No well-groomed broadcasters on the sidelines. Four young men in camouflage stand at the entrance to the field, ROTC students from PBA, serving as color guard for the evening, readying the flags. Young men in orange jerseys stretch and sprint on the field, loosen their arms. A broad-shouldered catcher dons his mask, outfielders play catch, parents and girlfriends find their seats.

Country ballads blend with Christian music in ways that make this experience more powerful and real. The game is free. Hundreds of seats all for the taking, no questions asked. I find mine and snap a picture of it, feeling both pleasure and sorrow. I was born on November 8th. Eight is my favorite number. A big bright jersey hangs in the home dugout tonight, but no one will be wearing it. Number 8.

All the young players sport blue wristbands inscribed with the words Team Carter and Isaiah 40:31, referencing their Coach's charitable foundation, together with his favorite passage of scripture:

"those who hope in the LORD

will renew their strength.

They will soar on wings like eagles;

they will run and not grow weary,

they will walk and not be faint."

Just before 7 p.m. the crowd grows quiet as a few family members enter the ballpark through a small gate out in left field. They take a long, unhurried walk across the grass. Moments later, a golf cart approaches through an opening in right field. Everyone in the crowd stands up. About 500 of us.

Gary Carter greets his team of players one by one, while his daughter Kimmy (PBA's winning head softball coach), his wife Sandy, and tiny granddaughter watch from just a few steps away. "Let's get a win tonight!" Coach says to all his boys.

"He wanted to be here for his guys," his daughter Kimmy will say.

Earlier today I read about Gary Carter in The Palm Beach Post. I read about how he'd showed up at his team's first official practice back in January, walking with the aid of a cane yet celebrating the beginning of a new season: "Guys, the day's finally here! It's spring! Let's get after it!" That's how 6'2" Logan Thomas, tonight's starting pitcher (who will soon throw a first-pitch strike), remembers it.

Carter's life has already become a story.

Fans honor Gary Carter lovingly with applause and silent prayers. And then the formal part of the evening begins. It starts in a way I've never seen before. We don't hear anyone cry, "Play Ball!" Instead, a campus pastor - standing just behind the neatly-painted lines of home plate, very near the catcher's spot - delivers a prayer for all to hear. "Give him peace," he says, "and give him power."

Power. While all the fans bow their heads in prayer, I think about power.

Bottom of the 10th. Boston 5, New York 3. The Mets are down to their last out on October 25, 1986. Everyone remembers this as the Bill Buckner game. I have always viewed it as the Gary Carter and Mookie Wilson game. Everyone remembers '86.

The count stands at 2-1, Carter at the plate. In a show of relentless grit and determination (more than power, it seems to me), he singles to short left field, and I stare at the cube television in disbelief. Then I behave idiotically. I run around our California bedroom screaming, pumping my fists, jumping up and down on a full-sized bed where my baby sits gazing at the television from his bouncy seat. He is but four months old, and he's watching the game. I pull him out of his canvas lounge chair and twirl him all around the room. I just want to share the game with him.

On February 1, 2012, Gary Carter views the PBA home opener from the press box with family members and close friends Tom Hutton and Jeff Reardon. "His whole life is baseball and the Lord, and of course his family," Reardon has said. An ailing Carter watches three innings of Florida baseball, and then it's time to go home.

The PBA Sailfish trail Lynn University 3-2 as they head into the bottom of the ninth. Let's get a win tonight. It's spring! Let's get after it! With two outs, Travis Murray - who majors in biology and envisions a career in medicine - delivers the game-winning RBI single. Travis is a catcher.

Despite a battle with aggressive brain cancer, Gary Carter remains a smiling inspiration to his players and fans. This is what we will read in the morning paper tomorrow while we eat breakfast on the patio.

The team stands in a circle of prayer in deep right field. Remaining in Seat Number 8, I replay a scene from three hours earlier. Gary Carter moves toward the home dugout from that same corner of the field, riding in the rear of a golf cart, traveling slowly along the first base line, facing backwards as they appoach home plate from first, circling around the catcher's box and heading inevitably yet curiously toward the bag at third - not in the counter-clockwise way that baseball usually moves - then down the left-field line, far away from us, and disappearing through a small opening in the wall. As that cart makes its gentle turn around home plate, I press my right hand against my heart, and with the other I wave goodbye.

His Grace is reaching for us

His Grace is reaching out

Listen to the sound, listen to the sound

Wherever you are.

Please click here to view Gary Carter's final home opener.

Click here to watch Hall of Fame acceptance speech.

January 16, 2012

The Off Season

"It breaks your heart. It is designed to break your heart."

I am taking a break from baseball and baseball writing.

See you in the spring!

"I was counting on the game's deep patterns, three strikes, three outs, three times three innings, and its deepest impulse, to go out and back, to leave and to return home, to set the order of the day and to organize the daylight."

- A. B. Giamatti, "The Green Fields of the Mind"

October 17, 2011

Men and Moneyball

"I think about baseball

virtually every waking hour of my life."

- Bill James

Good face. Good jaw.

Five tools. Clean stroke. He’s cheap. Buy wins. Buy runs. The what? Rich teams. Poor teams. Who’s that? That’s Pete. So what?

Yes. Please.

Shake things up. Who are you? Yes, he does. You do not. Pile of crap. Who’s that kid? Friend of mine. He can’t throw. He just did. You do not. Teach? Which one? So? So what? You got kids? I’ll tell him. What’s the point? What was it? What was it? Is that it?

You did good.

Pops off the bat. He gets on base. What do you do? I went to Yale.

I asked you to do three. Text me the play by play. I don't watch the games. Well, hey, good luck with that.

What a dump.

It’s hard to see, but it’s there.

We will have changed the game.

________________

“Moneyball” is a film full of men speaking largely in monosyllables. This could mean that its screenwriters possess a vocabulary roughly equivalent to that of a five-year-old, which is clearly not the case, or it may suggest that the world of baseball is full of Neanderthals who grunt for a living, which on some level might be true. But I think there’s more going on here.

The complexity of baseball is belied by the apparent simplicity of its vocabulary and its basic numbers, such as 3, 9, 6-4-3, and 0.

Monosyllables function eloquently and purposefully in “Moneyball.” They are deceptively simple words that create important, urgent, and witty rhythms; they cut through nonsense in getting at the essence of baseball; they represent an earnest attempt to apprehend the truth of a game and its people, and perhaps an accompanying desire to manipulate these truths.

When voiced as a question – as, for example, when Billy Beane first encounters the bright young economist Peter Brand - monosyllables can establish a sense of impatience, urgency, and passion. They are especially effective when voiced by a competent actor: “Who are you? What do you do?” Repeating his simple question in a tone of eager curiosity and wonder rather than condescension or disdain – “Who are you?” - Brad Pitt emphasizes “are” instead of “who” or “you.” It’s an early sign that this film is seeking to venture into more serious ontological territory.

One of the most famous speeches in our language, after all, is a soliloquy that wrestles with the idea of being. The lines of that speech are memorable in large part because Shakespeare chose monosyllables for the soliloquy's first line in lieu of fancy King Jamesian language and arrogant political rhetoric. To be or not to be. Language doesn’t get much simpler than this.

Monosyllables effectively establish the rhythm of human conversation and convey personality as well as any costume, facial expression, or idiosyncratic gesture. “Yale. I went to Yale.” The monosyllables in “Moneyball” succinctly articulate theories to be argued or refuted: buy wins and buy runs, for example.

Monosyllables and awkward pauses are a very real part of ordinary discourse, and many of us speak best in silences: “All moved in?” “Yeah. Yeah.”

Suddenly, however, a polysyllabic word breaks the monotony of simple speech, and it makes all the difference in this film, both rhythmically and conceptually. “Economics. I studied Economics.” The audience takes heed. Billy is acutely interested. A friendship is beginning, an engaging character taking shape. Here in a cubicle in the middle of Cleveland is a bright young man who is clearly holding something back; he cannot wait to bust out with the excitement of what he knows about baseball.

Monosyllables are important in “Moneyball,” because it is against the backdrop of simple language and old ideas that bigger words and newer ways of thinking about the game begin to make sense and gather momentum: “We create him in the aggregate.”

“The what?”

The veteran scouts sitting around a conference table at this “dump” of a major league facility are real men playing themselves, speaking in monosyllables as they evaluate other human beings, and the screenplay is better for it, gruffly and endearingly so.

As numbers become higher and the formulae more challenging, the characters' syntax grows more complex, as do their relationships. In Bill James’s world, numbers are language. When Billy Beane challenges his new assistant, an easy numeral comically gives way to higher digits. At the same time, the film’s language moves from monosyllabic speech to phrases that are more sophisticated both syntactically and morally, and the new partnership subtly shifts to a higher intellectual and emotional level.

“I asked you to do three. How many did you do?”

“Forty-seven … actually, fifty-one, I don’t know why I lied just then.”

Brad Pitt spends a fair amount of screen time with bits of food as his prop. Seeds, coffee, popcorn, junk. “I’ll tell him,” he says, while stuffing an entire Twinkie in his mouth. “Well, hey, good luck with that,” David Justice says to Scott Hatteberg while munching on cereal in the clubhouse. Monosyllables are especially entertaining when voiced with food in the mouth.

Quick words create one engaging scene after another in a fast-paced script. The rhythm of “Moneyball” is one of drive and urgency. At various points along the way, fewer words allow for better facial expressions. It is during the silences of the film that we notice an economist moving his eyes, a mind at work, a coach who feels devalued.

Whether a scene is comical, or tense, or bittersweet in nature, monosyllables give the actor important opportunities for expression. When Carlos Pena learns that he has been released, his reaction - like that of the assistant general manager - is astonishingly simple:

“Is that it?”

“Yes.”

Whether or not this is an accurate transcript of what actually occurred between Pena and DePodesta, the scene works, because its compact, monosyllabic lines leave plenty of room for pain. Upon learning of the Giambi and Pena trades, Phillip Seymour Hoffman blinks twice while listening to Pitt; then he moves his eyes sideways, prior to raising a question that he actually voices as a fait accompli statement.

“You traded Pena.”

No hysteria, no screaming outburst, no exclamation points, no grandiloquent speech. It’s baseball talk – understated, full of tension and emotion.

The monosyllable often rescues Billy from sentimentality in the nick of time, just as he’s about to display a more tender, vulnerable, or noble emotion: “What a dump.” Beane’s parting words to Pete near the end of the film are all monosyllables. His is a simple, colloquial, yet heartfelt farewell.

Male voices dominate this film, but a female presence softens it. Curiously, though, it’s not a wife, girlfriend, or personal assistant who provides the love interest. The movie doesn’t really need a romantic subplot. There’s no Glenn Close gazing beatifically from the outfield toward home plate, no Annie Savoy reading Walt Whitman to a frisky player. In fact, as in Moneyball the book (which names only four women in its index – count them: four), the female characters in this film are fleeting presences. They brew coffee, issue bitchy remarks in the clubhouse (“Hey, get outta my shot!”), whisk a child away from a business meeting. Portrayed in less than a minute of screen time by the ever-lovely Robin Wright, Billy’s ex-wife receives him in her cosmetically perfect living room whose Zen décor seems to cry out, “I'm so glad I don't have to live that baseball life with you anymore,” though one might sense a hint of ambivalence and regret in her enigmatic expression.

Incidentally, Bill James’s wife Susan McCarthy makes an appearance in the footnotes of Moneyball: “Bill hid his interest in baseball when we first started dating. If I had known the extent of it, I’m not sure we’d have gotten very far.”

When Billy Beane returns to Oakland after his off-season meeting with John Henry in a dreary Fenway Park, it’s Peter Brand who assumes the place that a woman might normally occupy, upon welcoming the main character home. Their conversation reads like a script intended for a couple sitting at the kitchen table late at night and speaking intimately about their future, but in Billy’s world, the important moment of connection exists between men, and it takes place not at home but in the dim light of a clubhouse:

"What was it?" Pete wants to hear a dollar amount.

"Doesn't matter."

"What was it?"

"Does - n't mat - ter."

Billy’s daughter is his sweetest and simplest love interest; she is the antidote to the film’s harsher outbursts – the throwing of chairs across a room, the upturning of coolers in the clubhouse and shattering of glass, the lonely moments of cruising and reckless driving. Casey predictably follows these more violent scenes, and it’s her job to show that Billy is capable of sustaining a personal relationship outside the world of baseball. It is in his daughter that we see Billy’s capacity to love another human being.

Their interactions take place in a music store, an airport terminal, and in the kitchen where they eat ice cream together. She’s kept at a safe distance from the field, however, and beyond the confines of baseball, as if protected from the world of men, as if the film doesn’t know quite where to place her. She exists outside the main plot, and her influence is strongest when manifested as a sweet voice in Billy’s car when she’s not even physically present.

These interludes are endearing, but in my view, the parenting scenes seem to have been lifted from another film. They interrupt the honest momentum of the story, robbing it of other potentially dynamic and meaningful baseball moments. Maybe the audience welcomes the quiet relief of a domestic scene, but this is a story that can’t afford to slow down too much. And you can’t rush or force a relationship with a daughter.

Much as I yearn personally to see admirable women in baseball movies and solid father-daughter relationships, I’m not convinced that these components are essential to Moneyball’s success. The relationship between Billy and Casey is believable and sweet, but in terms of energy and chemistry, it doesn’t come close to matching the gruff tenderness we witness among men, or the surprising depth and curious intimacy that evolves so much more authentically and satisfyingly between Billy and Pete.

A child’s pure voice offsets the grittier world of baseball with lyricism and tenderness, but the lyrics of her theme song (aptly titled “The Show") seem made for a different kind of film. You may have heard the tune a few years ago, in fact, in an Old Navy commercial. Kerris Dorsey's rendition in "Moneyball" is undeniably lovely:

I'm just a little bit caught in the middle

Life is a maze and love is a riddle

I don't know where to go I can't do it alone I've tried

And I don't know why

Slow it down

Make it stop--

Or else my heart is going to pop.

Her solo brings tears to Pitt’s eyes, but the song’s “dum dee dum, duh-dum dee dum” refrain dumbs down the film intellectually if not emotionally and seems incongruous in a drama whose cerebral center is Bill James and the ideological shift toward sabermetrics.

Far more effective is a subtle yet powerful musical theme that plays quietly at key moments in “Moneyball” while the plot drives purposefully forward. The haunting leitmotif begins tentatively as five simple notes. It’s a warm, tender, benevolent music from elsewhere, hinting at possibility and shimmering with anticipation. The intervals are unusual – not your standard harmonic progression in predictable thirds or fifths, and it’s not easy to determine whether the key is minor or major: F# - F – C# rest. G# A#. (It took me a while to figure out this sequence while playing it on the piano after seeing the movie a second time. I was a little obsessed with the melody, in fact.)

You could say that this theme is the musical equivalent of monosyllables. It’s deceptively simple. Try playing it if you have a keyboard. Take time with each note, repeat the phrase, then waver slowly between G# and A#, and you will experience not just an important part of the “Moneyball” soundtrack but the soul of the film.

This music was borrowed from a curious source, a post-rock band that recorded “The Mighty Rio Grande” in 2007; it’s a brilliant choice for “Moneyball,” especially when intertwined with the soulful cello and warm ostinato of Mychael Danna's moving orchestral score.

The gentle tapping of a muffled drum joins this very basic angular melody in a primitive sound that resembles the beating of a human heart. One feels a growing sense of urgency and quickening in the film as an exciting mathematical idea begins to take shape. Music builds suspense unobtrusively and subliminally throughout “Moneyball,” advancing and enhancing much of the rough action with accompanying lyricism. The “Rio Grande” melody functions as the film’s dominant theme and serves as a musical metaphor for its central idea: “We will have changed the game.” Future perfect tense.

Near the end of the film, Brad Pitt voices a sentimental question: “How can you not be romantic about baseball?" The line is cloying, out of character, and entirely unnecessary, in my view, because the romance of the film comes across nonverbally in the game itself, in baseball’s imagery, in the expressions on Billy’s face, and Peter’s too, in the tension and affection among men, and so poignantly in the quiet richness of a musical score that builds toward the film’s stunning climax.

Baseball is not just a tactile and visual thing, nor is it a purely mathematical idea; the game is also auditory in nature. When one is watching a good baseball movie, it isn’t enough to hear the crack of the bat and the cheering of a crowd at its climax. Music and silence are essential in reaching the psyche and lifting the material to the level of art.

The intelligent thesis of Michael Lewis’s best-selling Moneyball (2003) is now old news, and Jamesian sabermetrics are no longer the exclusive intellectual property of Billy Beane, the Oakland A's, and other teams with inferior resources. Moneyball is not the silver bullet, after all, and there is no single magic formula. The intangibles still matter, and so does character. Just ask anyone in Boston.

"Moneyball" is not a documentary of one season, nor is it simply Hollywood’s version of a good book. Film is not real life. It’s not biography or ESPN. In two hours, a movie cannot begin to tell all the complex human stories that combine to form the truth of baseball in our time.

Film is art, and as such, it has to become a metaphor for baseball and the human condition, just as an amusing video clip enables Pete to teach Billy Beane a lesson about himself:

“It’s a metaphor.”

“Yeah, I know it’s a metaphor.”

We sit in the darkness of a theatre, hoping to experience something that resembles baseball. Good baseball movies like “Moneyball” have to feel like the best ballgames we've ever seen. They have to capture the tension and the joy.

“Moneyball” seeks to take us into a territory that ultimately transcends numbers and personalities and our best efforts to measure and control these things. Built upon monosyllables and amplified with a rich musical score, the film invites its audience to participate in the authentic excitement of a new idea, and then moves toward a higher plane of intangibles and into the realm of art, which in the end is what all good baseball becomes at its best. This is where “Moneyball” takes me, as Scott Hatteberg drives the ball out into a vast darkness.

August 17, 2011

Gone Too Soon

The river bears no empty bottles, sandwich papers,

Silk handkerchiefs, cardboard boxes, cigarette ends

Or other testimony of summer nights. The nymphs are departed.

And their friends, the loitering heirs of City directors;

Departed, have left no addresses.”

T. S. Eliot, The Waste Land

________

The Cape Cod Baseball League's 2011 season ended with the Harwich Mariners taking a three-game series from the Falmouth Commodores to win the championship. Players from the Chatham A’s had packed their bags and left town long before that final victory. Once the winningest team on the Cape, our hometown Anglers (formerly known as the Athletics until the MLB moved in and dictated change) didn’t even make the playoffs this year, and now they are gone.

The season is done. The stats are in the books. Field managers are already looking toward next summer’s rosters, considering elite pitchers and top prospects who might bring to the Cape their strong arms, big bats, and a winning season.

There’s still plenty of baseball to be played on other fields, in other small towns, and in big cities everywhere. All the college boys whose wood bat seasons just ended will soon take the first swings of fall ball. In many ways baseball never really ends; more and more it seems to me that this is true. But our town has undergone a sea-change. The field near my house doesn’t look the same. Main Street doesn’t feel the same. All our evenings play out so differently now, the rhythms of life substantially altered.

Perhaps the end of a baseball season - especially a premature ending such as this - prepares us for other endings and losses; there’s a sadness in it.

The refrain of a country song has been echoing lately on the radio inside my head. I don’t particularly like the song, but it keeps playing anyway, like a top-40 favorite on a local FM station: "Gone like a freight train, gone like yesterday . . . ."

You'll likely hear this song if you visit minor league ballparks and college stadiums. It's not an uncommon outburst after a home run ball travels over the wall. The Montgomery Gentry ditty is an odd choice, though, because the song's sentiment is wistful, melancholy, and full of regret - hardly celebratory in tone. The song isn't about a ball, of course; it's about a woman.

Gone like a '58 Cadillac . . . gone like all the good things that ain't ever coming back, she's gone. Gone. Gone. Gone.

There are no more kids at baseball camp every weekday morning, boys and girls in t-shirts truly believing they'll make it to the big leagues someday. No more college flags flying proudly in the gardens of families who opened their homes and refrigerators to young players, surrogate moms and dads who showed up faithfully at every single game. No more pickup trucks and cars with decals and license plates from far away: Baylor, NC State, Clemson, Tarheels, Gamecocks, Hogs, and the lone star of Texas in red, white, and blue. No more relievers sitting on the crooked bench they call a bullpen; no more uniforms of royal blue and white. They're gone.

In a few years, we’ll be watching television, my son and daughter and I, aunts and uncles and cousins, and we’ll see them again. And so will you. We’ll say we know them. Danny Espinosa at spring training. Evan Longoria at the All-Star game. Andrew Miller on NESN. Chris Getz playing second base, Matt LaPorta at first, David Huff in an Indians cap, taking a line drive in the face. “Hey, I know him!” At least we felt as if we knew him. He played ping-pong with my son the batboy, once upon a summer evening, inside the VFW hall out near the town dump.

"We saw him play . . . I watched that kid pitch . . . We remember that win . . . I was there . . . .” Almost every fan remembers baseball this way. The achievements of others lend dignity and meaning to our own anonymous lives. The human connection, however brief, resonates for years. Hey, we knew him.

They’re here; then suddenly come August, they’re gone. Gone like a freight train. Playoffs or no playoffs, the abrupt ending always startles us. It's enough to knock the wind out of you for a few seconds at unexpected and random moments. Gone like yesterday.

The country song is playing again, this time in counterpoint with a Neil Diamond elegy dating back to my high school years.

Jesus Christ, Fanny Brice, Wolfie Mozart and Humphrey Bogart and Genghis Khan and on to H. G. Wells. Ho Chi Minh, Gunga Din, Henry Luce and John Wilkes Booth, and Alexanders King and Graham Bell. Ramar Krishna, Mama Whistler, Patrice Lumumba and Russ Colombo, Karl and Chico Marx, Albert Camus. E. A. Poe, Henri Rousseau, Sholom Aleichem and Caryl Chessman, Alan Freed and Buster Keaton too.

And each one there has one thing shared: they have sweated beneath the same sun. Looked up in wonder at the same moon, and wept when it was all done. For bein’ done too soon. For bein’ done too soon. For bein’ done.”

Now obsolete, the Chatham A’s 2011 calendar is still visible in a sidebar on the team website. As my computer hums its dull sound, I’m looking at the early days of August, now gone, wondering at the ways in which we measure the passage of time. Wareham @ Chatham. Chatham @ Harwich. Orleans @ Chatham. Chatham @ Orleans. Followed by a bunch of empty days that say: Off. Off. Off. Off. Off.

Something tightens in my chest.

And then a few lines of poetry emerge from who knows where, bumping Neil Diamond out of the lineup: “What will we do? What will we ever do?”

"What shall I do now? What shall I do? / I shall rush out as I am, and walk the street / With my hair down, so. What shall we do to-morrow? / What shall we ever do?"

The hot water at ten. / And if it rains, a closed car at four. / And we shall play a game of chess, / Pressing lidless eyes and waiting for a knock upon the door." *

All the summer people still crowd our resort town with Land Rovers and Volvos and gleaming black Escalades with plates from New York and Maryland and Vermont, but the field is empty of fans. Ballplayers who were loaned to us have returned to their home fields, their lives at school and fall practices, their mothers’ kitchens, their apartments and girlfriends, homework and tailgate parties while we remain, trimming hedges, gathering bundles of clippings, sanding and painting the trim, then looking out at a changing sea.

The Cape League season winds down in rain and fog. The boys of summer depart abruptly, their vehicles bound for Chapel Hill, Richmond, Plano, Memphis. Their dugout is quiet, and we are left to gaze at an empty field. Never will this same group of young men live in town together, play as the team they were for one brief season, when warm weather and long days felt permanent.

Two parking lots stand empty behind the Community Center and The Red Nun Bar and Grill. Trees in full leaf near the snack bar quiver, but nothing is moving on the base paths nearby.

I park on Depot Street across from the fire station and survey a quiet field. The landscape is already altered, chalk lines stretching diagonally from infield to outfield, obtruding on the geometry and integrity of the diamond, defining boundaries for a soccer game, a sport that is played mostly without hands. My eyes are growing weaker with age, but as I look toward home plate without my glasses, I see a man standing in the batter’s box, swinging an invisible bat. He has a strong grip and a decent swing. His back foot pivots slightly in the dirt. The announcer has just called his name for all to hear. The hitter is a key player in the line-up, an athlete at the peak of his career in the prime of life, excited about a winning season and a promising future.

In truth, the person I see is a man alone. He is well past his prime, and there is no team. The field is empty but for him, the press box shut tight. He holds an imaginary bat in a game that is not real.

The team is gone, the season done, and so many players will never warm up on this field again. There’s an ache in that thought. Something akin to sorrow and loss and emptiness, though I’m not sure that emptiness can actually ache.

A couple days later, and I'm on the road again. While running errands around town, I make a point of driving by the field as I often do during the off-season - just to see the place, pausing to remember and preparing to feel sad again. But this time the ballpark isn't empty as I expected it would be. Nor is there a lone fellow protecting the plate. I pull over, stop the car, and park beside the hill that rises above a lovely green expanse of grass.

Just below me down in center field, an important game is taking place. A young father is pitching, and his small boy is swinging for the fences. (The fences are about twenty feet from home plate.) A folding beach chair serves as backstop and catcher.

Nothing has ended, after all. It’s simply beginning again.

* selections from T. S. Eliot, The Waste Land, 1922. facsimile edition.

August 3, 2011

Road Trip to Elsewhere

The signs I viewed soon after touching down in central Mississippi sounded nothing like home. A town named Pearl. The Chunky River. Holy Revival Tabernacle and Minnow Bucket Road.

Two quick flights from Boston had taken me to another world.

In retrospect it seems odd that I didn’t notice a single ball field during my visit to the Deep South, a region I've long associated with athletics: Archie Manning and the SEC, Eli Manning and the Ole Miss Rebels, Jerry Rice, Boo Ferriss, the Bulldogs at State, and that retired guy from Hattiesburg who throws a football in Wrangler commercials.

Oh, I saw plenty of uniforms on this road trip, but they had nothing to do with football or baseball. So many uniforms. Atlanta, Charlotte, Jackson, Meridian: so many men and women in uniform. Combat boots on young recruits, women with crisp caps and hair pulled back tight, infantry and Air Force and Airborne. Camouflage, flight suits, and Navy blue.

Many faces displayed an otherworldly expression, as if they were gazing at something far away.

At Logan Airport, I watched one mother bid farewell to her U. S. Army son. There was nothing she could do as he disappeared inside the sterile jetway. She left the gate area slowly, leaning toward someone who might have been the young man's dad, seeking comfort and strength. I watched until she too disappeared from view.

When my Delta flight landed in Atlanta, most passengers remained seated and silent. No one rushed to stand up and grab belongings at the sound of the bell. Military personnel had been invited to deplane first, so that is what they did, while the rest of us solemnly applauded. A handsome young man in camouflage departed, his final destination: Kuwait. “Thank you, ma’am,” he nodded, and I watched him go. He looked so young, so very young. Thank you.

They journeyed alone and in small groups; said their goodbyes; boarded their flights. Inside a quiet terminal in Jackson, Mississippi I witnessed a poignant homecoming, the scene like so many others even more affecting because it was so subdued: three small children formed a circle around their dad, sheltered by a larger gathering of loved ones surrounding a lieutenant now safe at home.

I traveled with a pair of dog tags in the pocket of my jeans.

As I walked and as I watched, passing all the snack bars and ticket counters, rest rooms and Hudson newsstands, so much seemed superfluous. Newspapers, magazines, cosmetics, bestsellers, the sports pages. That world ceased to matter. I was traveling to meet my son, and it never occurred to me to check the box scores or MLB standings. Baseball headlines and trade deadlines suddenly seemed remote and insignificant, and the seriousness with which others approached those subjects struck me as amusing.

I watched a single mom happily diapering her baby boy, just as I once tended to my own children. The infant's name was Marcus, a distinguished and manly name, or so it seemed to me. A young father struggled with his diminutive twins, one of them screaming a newborn cry, a sweet and fragile sound that instantly took me back to blissful mornings and wakeful middle of the nights.

My children had always traveled well. The oldest loved an airport experience, no matter what our destination. Delayed and connecting flights never upset him; he'd stand patiently at picture windows, studying the activity on the runway and imagining flight. Nothing engaged his attention more than pilots in cockpits preparing for takeoff; orange sticks waving an aircraft into the gate; the slow rollback.

Last Thursday morning he greeted me early, a grown man all dressed and ready for work. He wore a khaki flight suit, Marine Corps dog tags laced into his boots.

Two hours later, I stood on a short runway in Lauderdale County under very uncertain skies as a T-45 Goshawk approached, its beam of light shining golden just as it should, a Navy jet swiftly touching down, then taking off again.

Inside a small hut beside the airstrip and outside it as well - just steps from those painted lines you see in the photograph - I stood and watched six young men rehearse and refine their touch-and-go landings. Their jets came straight at me, one after another, a golden light on the nose of each aircraft assuring me (and their mild-mannered yet acutely focused flight instructor) that if this patch of asphalt were the more fluid terrain of a carrier out in the middle of the sea, they would catch a hook.

The strike zone matters.

For two whole days, I didn’t think once about baseball. The subject never even crossed my radar screen. I saw no highlights or web gems on tv, checked no game summaries, and I survived without wireless newsfeeds from my colleagues in the business. Players' names became faint sounds in the distance, like friends I had known long ago . . . .

From time to time I wrestle with some questions, and maybe you do too. Is baseball ultimately just a frivolous pursuit, or is it worthy and significant? Does the game lift me up and fill an empty space, or does it drag my spirit down? Is it mostly an escape from pain and trouble, and thus unreal? Or is it real?

Maybe baseball isn't the huge thing I've made it out to be. In the end, it really isn't the thing I love most in life.

For the past week or so, the field of my dreams has been an airfield, its painted lines configuring a new geometry, a stretch of asphalt functioning as a metaphor for fluid runways that move in the middle of turbulent oceans where there is no manicured grass to be seen.

Last Thursday morning I wore foam earplugs to muffle the exhilarating noise of jets touching down so close we could almost touch them, then swiftly taking off again in well-choreographed, intelligently-executed patterns of touch-and-go. The powerful music they generated didn't manifest itself as something to be heard. No. Sound waves became a tactile thing felt palpably in the chest, not anywhere near the ears. An intense rumble of vibrations very close to the heart.

In less than 48 hours my son would touch down on a moving runway in the middle of the sea - not just once, but ten times. Alone in the cockpit, he would be G-suited, helmeted, and belted in for landing and takeoff, protected beneath a transparent canopy and furnished with an ejection seat. Touch and go. Lap around the boat. Catch a hook. Then catapult off the deck, accelerating over uncertain waters in a manner that most of us will never know, from 0 to 120 knots in approx. two seconds.

Upon finishing his required carrier landings, he sent a message home, delivered in words that were typically succinct and matter-of-fact: CQ complete. And then came a photograph of USMC wings pinned close to my son's heart, his name inscribed in letters of gold.

"They will soar on wings like eagles;

they will run and not grow weary,

they will walk and not be faint."

- Isaiah 40