Rebecca Stonehill's Blog

September 25, 2025

A History of Understanding in Nine and a Half Steps

Last night I read a poem at Kimberley Moore’s mid-week Music & Words event in Norwich which I was invited along to. I love the magic that Kimberley weaves at these events – it’s a beautiful, intimate pottery studio with fairy lights and beautiful artwork and plants and it feels like we’re in someone’s living room.

This is my ‘proem’ that I performed (it’s not quite poetry and it’s not quite prose). It’s quite long, so I’d recommend making yourself a cuppa before you sit to read it. Before I read, I shared with the audience Nina Simone’s words: An artist’s duty is to reflect the times. Here is my response to reflecting the times.

A History of Understanding in Nine and a Half Steps

STEP ONE

It’s 2030

and I ask you to allow me to dream.

A young woman of twenty-six years old

walks along a coastal road as the sun glints off the Mediterranean.

Desert finches are buffeted in the warm wind above her

as they dart in and out of the branches of young olive trees

that line the road.

Eventually, she reaches her destination

and she walks the path she has been down so many times

until she reaches the headstone that bears her sister’s name.

She bends down, brushes a leaf away, smiles.

She thinks of her laugh,

the grace of her drawings,

the way she danced with abandon when certain songs came on the radio.

The young woman sits there for some time,

grateful for the breeze that cools the heat of the day.

Now she will visit her best friend,

twenty-seven headstones up the path

and forty-three to the left

and then her aunt,

and then her neighbour,

and then her professor, the one who brought Shakespeare alive for her.

There is a route she takes.

It is familiar.

It is comforting.

They never saw the re-planting of olive trees,

the re-building,

the permanent ceasefire.

So she carries it for them;

does everything she does now for them,

and for all the others.

She sees a flash of colour bolt past her and follows it.

It is a sunbird, settling on a jasmine bush nearby and using its curved beak to

extract the nectar.

She watches, transfixed, not wanting to move a millimetre in case she scares it.

She thinks, everything is wrapped up in this little bird: freedom, life, colour, courage.

She thinks, there is always hope.

There is always hope.

Step Two

I’m cleaning the bathtub.

It’s been a while and I’m scrubbing hard when suddenly,

I start weeping.

I’m not expecting it and it takes me by surprise

and I sit back, waiting for the tears to stop.

But they don’t, and the scrubber is now abandoned

and I surrender to the grief.

To the not understanding.

Perhaps somewhere in my memory there is a pocket

that has triggered this.

Perhaps I am remembering my three children

when they were small, their smooth soft bodies in the tub,

their squeals and shrieks and splashes and shampoo-saturated hair

standing stiff upon their heads.

And perhaps I cannot comprehend how it must feel

to return home from working a long shift in a hospital

to find nine of your ten children dead.

Yahya, Rakan, Raslan, Jubran, Eve, Rivan, Sayden, Luqman, Sidra.

All gone.

Step Three

If we had been alive at the same time,

we would have been friends, Anne Frank and I.

I’m ten years old and I decide with that ferocious certainty of children,

because I understand Anne.

I understand her irritations and sadness,

her loneliness and love, and that fierce urge to write.

And alright, I don’t know what it’s like to be hidden in an annexe

and to live in constant fear of being discovered.

But I’ve grown with stories of my father’s family

perishing in the camps,

the stars of David sitting solemnly beside their names in the family tree,

the survivors scattering to Israel and America

in search of a new life.

So I claim Anne as my confidante

and bind myself tightly to her.

Yes, we would have been close friends, I think.

Maybe even best friends.

Step Four

I’m in Parliament Square. The rain is

ricocheting off my waterproof coat and

I’m focusing on writing a sign with a

black marker pen.

There it is, I finish it and catch

a glimpse of a small band of men

standing amongst our group, faces like iron,

holding aloft signs that say There is No Genocide.

It slaps me in the face

and I turn my own sign around:

I Oppose Genocide.

I Support Palestine Action.

But a mere twenty seconds later a police officer appears

and reads me my rights.

He tells me I’m being arrested under Section 13 of the terrorism act.

That I cannot support a proscribed organisation.

I am taken aback it’s happening so quickly

and I say, ‘You don’t have to do this.

You can act on your conscience.

You know this is wrong.’

He clears his throat and replies ‘I’m just following orders.’

And I can’t help myself, I tell him

That’s what they said in 1930’s Germany.

He’s angry now and clasps my wrists tightly together

before snapping the handcuffs around them.

That’s too tight, I say.

But he just leads me towards the police van,

rain teeming down

as we step over puddles and around too-close cameras that click in my face.

Step Five

I’m eighteen and away from home alone

for the first time.

I have been assigned to a kibbutz an hour

from Tel Aviv, a place of sharon fruit and avocadoes and oranges

and low-lying buildings hugging the contours of this rain parched land.

I take up a habit of a smoking Noblesse cigarettes

and drinking more than is good for me

on those warm nights.

I fall into bed far too late and get up

far too early to irrigate the avocado trees

and learn words of Hebrew that sound exotic on my tongue:

Bevakashan. Boker tov. Sliha.

I fall in love with an Israeli soldier

who comes home at the weekends from military service.

He is dark haired and swarthy and

when he tells me about the patrols he goes on

and those crazy Palestinian kids throwing rocks at his jeep,

one of them nearly shattering the windscreen,

I think, poor him, what a nightmare.

He can’t wait to leave the army,

to travel,

to work,

for his life to start.

I think, imagine having to constantly defend yourself

and your country like this.

What’s wrong with these Palestinians anyway?

Several months later, and I’m putting up

a huge Israeli flag on the wall of my first university room.

I still wear the necklace that spells out my name in Hebrew:

Rivka and I start writing down phrases in a notebook,

for when I go back again.

Since my time on the kibbutz, my Jewish roots have taken

on proportions of immensity; I am newly bonded with the

far-flung aunties and cousins

and I start looking into ways

I can spend a year out in Israel.

I am smitten: with an ideal, a land, a language,

a soldier.

Step Six

As soon as I read her article in Al Jazeera, I feel

something shimmer like silver down the length of my spine:

Knowing.

It is knowing that she is the person I’ve been looking for.

It is half-way through 2024 and the latest war against Gaza

has been raging for over half a year.

I’ve been posting about it on Facebook, calling for a Ceasefire,

and one by one the far-flung cousins who I’ve

not had contact with for years pop up,

condemning me, shaming me,

telling me I don’t understand anything.

One tells me my father, if he were still alive,

would be ashamed of me.

Another says I will burn in hell.

I block them, one by one.

And I keep scouring the web for a Palestinian writer who

can run a writing workshop for Norwich Writers Rebel,

the group I run.

I imagine he or she will be from the Diaspora,

for I have no idea how to find someone in Gaza itself.

But then, there it is in Al Jazeera, the article about

the loss of the territory’s libraries,

there she is.

And it moves me, this article, not just for the rich, warm

wisdom of her voice, but also because

libraries have shaped me my entire life –

entering a cathedral of books calms me, soothes me,

just like I am soothed when I enter a forest.

Her name is Shahd Alnaami.

She looks young, not much older than my eldest

and I search for her on Instagram.

What do you say to a person you’ve never met

whose pain and loss and resilience sings

through their writing?

So I send a brief message, telling her I was moved

by her article and I stand in solidarity with her.

Two hours later, she messages back.

This is the start of a friendship I have come

to treasure like a glimmering dawn after a long night.

Two workshops later, and we leave one another

frequent voicenotes.

I can hear the drones and the bombs

in the background and sometimes she is scared

but mostly she is stoic.

There is always hope, she says,

breathing it like a mantra, again and again.

Hope, however fragile, she says, is an act of resistance.

This war against her people has made her wise beyond her 21 years.

I have never known courage like this.

Not when she loses her home twice

to airstrikes and starts living on the roof of her uncle’s house.

Not when she must endure the

desperate weeping of the neighbourhood kids,

begging for food, crying that their stomachs hurt from hunger.

Not when she loses her oldest and closest friend who she grew up with.

Not when her thirteen-year old sister

is pulled out dead from beneath the rubble

from her bombed building and Shahd says

that she still wants to do the workshop –

that her sister would have wanted that.

And sometimes – of course – that stoicism slips.

How can it not?

One night I see a post she has put

on her Instagram story. It reads:

Tell me one good reason to stay alive.

And something in me cracks and buckles.

I sit at the kitchen table and read it again and again.

It’s nearly midnight in Gaza

and I ask her if she wants to speak.

Who am I to say anything at all

with my fridge filled with food and

my mornings filled with birdsong; my family intact?

She tells me that her father, Ahmad, who was born in

the same month as me and who I feel such affection for,

went to the aid distribution point that morning to find food.

But instead of bread, he found bullets;

some were killed.

In the chaos he lost his only pair of shoes,

his money was stolen

and he returned home shoeless, breadless, cashless, traumatized.

I let her cry

as she asks me

Why do they hate us so much?

We only want to live in peace.

And I have no good answer for her.

I have no answer for her at all.

Step Seven

It’s my last year of university.

I’m still obsessed with Israel.

With resurrecting my Jewish roots.

I visit friends over there –

go on treks in the Negev desert and

walk through the sun-soaked souks

of the old Arab quarters and observe shabbat.

I decide to take a course outside my studies

called Politics, Economy and Society of the Middle East

and little do I know,

that this will change everything.

In this classroom, Arab scholars will lay bare the facts

as the region’s history unfurls before me in all its jagged rawness:

the Six-day war, the Sabra and Shatila massacres,

the intifadas and annexation of the West Bank.

I am stunned. Speechless.

The image comes back to me time and again

of the young Palestinian boys hurling rocks at

the armoured vehicle of the kibbutz soldier

as understanding edges in and takes root.

Didn’t he know? Didn’t he understand?

I read all I can get my hands on.

I join Friends of Palestine.

The Israeli flag comes down from my wall,

the necklace is removed,

the Hebrew phrase book closed.

When I see my dad, we have heated debates about

whose land it is – he laughs,

tells me I have chutzpah,

but that I’m wrong.

Imagine a painting, a family heirloom, he says,

that somebody has taken away from your family for two thousand years –

wouldn’t you want it back? Of course you would.

I find his logic ridiculous, and tell him as much

but he laughs again

and we agree to disagree.

You’re a passionate one, he says and smiles at me affectionately.

I think: there is so much I don’t understand.

I think: there is so much more to learn about this confusing, complicated world.

Step Eight

I’m sitting in front of City Hall in Norwich.

I’m holding the sign again,

yes, that same one that reads

I oppose Genocide. I support Palestine Action.

Just saying that here, now,

I could get arrested.

And if there are any police officers here amongst you,

you’re obliged to handcuff me.

But the thing is, that I do oppose genocide

and I’ll say it again and again

until my throat closes and my skin cracks.

And the thing is, that I do support Palestine Action.

Because they’ve never hurt anyone

and they only want to dismantle the

war machine that I also want dismantled.

I want the harm to stop.

The sun is pouring into my eyes

and I’ve wrapped my kuffiyeh around my head.

I thought they wouldn’t bother with arrests

out of the big cities,

but I realise quickly I was wrong,

for barely have we sat on the steps

than we’re surrounded by policemen,

all glaring fluorescent efficiency, like supercharged wasps.

I feel panic rise up in me –

I don’t want to get arrested again

and I know I could put my sign down right now

and move to the side where there’s a large crowd of supporters.

I turn my head to look at them and there’s a woman

holding a sign that reads

‘Palestinian children deserve to live.’

I can see the faces of my husband and daughter,

the strength and love that emanates from them,

and something in me breaks.

I drop my head and weep –

for the suffering, for the destroyed dreams,

for the rollcall of daily names cloaked in numbers.

My friend Jackie is sitting beside me and she is also crying.

I shift closer to her and her warmth comforts me as we clasp hands.

Even if I wanted to move, I can’t now.

I will continue to sit for the Palestinian children.

The Palestinian children who deserve to live.

I watch as my friends and comrades are peeled off the steps

until it is my turn.

I’m told I’m being arrested for terrorism offences;

I open my mouth and the words flow out like water over stones.

I tell them how the equivalent of a classroom full of children

are being murdered every day in Gaza

and I ask if they have children themselves.

But they keep saying I’m being arrested and that anything

I say can and will be taken down and used as evidence against me.

And every limb of my terrorist body is hauled up from the city hall steps

and carried by six police officers to a waiting van.

I see another friend make a heart sign at me through the window

and I smile weakly at her, close my eyes, and lay my forehead

against the cool glass.

This is too much.

I am exhausted by this.

Step Nine

It’s October 2025

and I ask you to allow me to dream.

The latest war against Gaza has been raging for 2 years.

I’m sitting again, with the same sign, in Parliament Square.

There are hundreds of people around me, waving Palestinian flags,

singing, drumming, talking, resting in the weak October sunshine.

I can see at least a few people in wheelchairs;

one of them is the blind man, going in for his fourth arrest,

and I can see vicars in their dog collars,

an elderly man with his war medals and a teenager who looks like he’s not

even left school, his blond hair streaked black, green and red.

A heaviness weighs upon me like lead –

here I am again.

There are well over a thousand people and it’s going to take a long time

to arrest us all.

I take out a book and try to read, but I can’t focus

so I close my eyes, welcome the October sun on my face, breathe slow and even.

And then, perhaps I feel it before I see it,

something shifting: an energy that was not there before.

When I open my eyes, what I am looking at I instinctively know will go

down in history:

this moment, this square, this constellation of people.

Picture this:

a policewoman. She’s in her thirties, hair smoothed back into a neat, dark bun

beneath her hat.

She is standing in front of a woman around the same age

dressed in medical scrubs, Doctor emblazoned on her front as she

sits cross-legged with the sign.

But the policewoman is not arresting her, she appears frozen – with what?

With indecision? With weariness? With suppressed trauma from having to arrest

these people she knows are not criminals?

I study her face, not tearing my eyes from her.

The policewoman is crouched down so the two of them are at eye level

and they are staring at one another intently.

And then….

Without a word passing between them,

the doctor shifts on the ground to make room for her

and passes the policewoman the sign.

She sits, staring ahead while the doctor writes out another one.

The press are there immediately, hungry for stories,

for the shot that will make waves.

And as I look at the two of them, sitting there shoulder to shoulder,

I realise something else is happening:

behind these two I see a policeman.

He is wavering; I can see he is fighting with his conscience –

every emotion flitting over his face and crossing his eyes

like clouds skudding across the sky.

I watch as he breathes in,

an inhale long and deep and brave

and then he does it; he sits, the sign silently handed to him.

It is happening, one by one,

like a wind rippling across a prairie,

members of the Metropolitan police force are holding up the sign,

some sitting, some standing,

all the way back over the sea of heads

to the statue in the corner of Parliament Square of Millicent Fawcett,

suffragist leader and social campaigner.

Her face is soft but determined, and

between her hands she is clasping a banner that reads

Courage calls to courage everywhere.

As I watch this extraordinary scene unfolding, unfurling,

I feel hope catching at me in a way it has not done

for a very long time.

I know that my grandchildren will learn and speak of this day

in their school of the future;

how it led to a revolt in the ranks

of the seats of power;

how a prime minister was pushed out

and support for an occupying country withdrawn,

not only in words, but in deeds.

How a new politics of care and kindness was established,

how one brave policewoman resisted

and the ripple effects of her act.

But for now, I simply sit with my sign

and I drink in this sight, my cheeks glistening with tears of gratitude –

that I was here to witness this;

that Millicent Fawcett’s words are right;

that courage does call to courage and

that there is always hope.

There is always hope.

Step Nine and a half

I am ten years old.

I have just finished reading The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank

and I lie back on my bed.

It’s hard to understand, but I know that my life has shifted in some way,

that I can never be quite the same having read this book.

I don’t understand why she had to die,

why so many had to die.

Something is planted in me at that moment:

an acorn that roots deep in my skinny ten-year old frame:

Injustice.

It is wrong.

It is wrong.

I want to live in a better world than this,

and I will help build that world.

I hug the book tightly to my chest,

close my eyes and smile.

Yes, we would have been best friends, Anne and I.

The post A History of Understanding in Nine and a Half Steps appeared first on Rebecca Stonehill.

July 9, 2025

Writing for Gaza – Stories of Resistance of Hope

On June 29th we held our second online workshop with Shahd Alnaami, a talented writer based in Gaza. Joined by people all around the world, the title of the workshop was ‘Writing for Gaza – Stories of Resistance and Hope’ and Shahd used Palestinian embroidery, tatreez, as the motif of her workshop, which included a moving video in which she interviewed her grandmother as they discussed this traditional craft.

Shahd has said that she is tired of being defined by pain and suffering and wanted the writing activities she designed to highlight the richness, colour and beauty of this traditional art form. She certainly did that, and so much more. Her gentle wisdom and courage in holding this space, even after a very stressful morning, was truly inspiring. One attendee afterwards emailed to say it was the best workshop she had ever been to. Another said ‘The experience makes me feel that the tip of my whole life had been touched … and helps me imagine I may explore well beyond the tip.’

Shahd is twenty-one years old. She has lost her 13 year old sister in this genocide and countless other people close to her. One of the questions asked was ‘Is there anything at the moment that helps you feel safe?’ Shahd replied that there is no safety, anywhere, at any time. As no international journalists are allowed into Gaza, we must shine a light on those voices from inside the region. There was no hatred in this space; only an outpouring of love, support and solidarity.

I am so moved and humbled by Shahd’s courageous spirit. The horrors that continue to take place in Gaza and across the West Bank have made me lose faith in humanity at times: our own government’s complicity (and now, with the proscription of Palestine Action as a ‘terrorist’ organisation); people’s ability to look the other way and not speak out, our ‘never again’ narrative shattered to pieces. And then I see Shahd, revising for an exam by candlelight, posting on social media about the birdsong that is still present in Gaza, picking herself back up after yet another tragedy, and somehow my faith is restored.

There were two writing activities over the course of the workshop and then right at the end, we asked participants to type into the chat one of the lines, phrases or words that stood out for them from what they’d written. With this, Shahd and I wove together the words to create a group poem. The power of collaboration. I hope you enjoy it.

The morning light; emergent not immediate

The light that brightens our future is already in us.

When you live a life you’ve made yourself,

woven by mothers,

hold and share love together, a thobe of colour for living

for I want only colours. Colours don’t weep.

The thobe sways as she walks; the stitched olive tree talks,

embroidered waves that lap against the shore

symbolise persistence, eternity, devotion.

Tatreez taught me how to let go, and how to be better prepared,

the embroiderers’ thread drawing us together and finding the whole.

We are not just thread and colour;

weaving our shared hope

we thread our lives with every stitch.

Thread by thread, stitch by stitch, we build the future together

Stitch by stitch, thread by thread,

memories stitched together joining the past and present.

I’ve laid under these quilts since I was a little child,

learning from my grandmother the weight of what a life is,

stories etched in us like tatreez,

grandmothers carrying the resistance.

Wake up, woman. Be a cypress.

I am dove, I always hold my space of peace and emanate this to the world

and you try to erase me, to erase my existence,

yet here I am, as present as the river and the sea, as steadfast as the cypress tree.

People should know the colours and symbols

of what is being eradicated rather than just our torn revenants,

for Love and Hope are stronger than Fear;

to appreciate and to create authentically is to be human.

Why fight for a better world

if it wasn’t for my daughter to live in a world

where she will dance in a world;

where she will dance with Palestinian children like her?

You can’t destroy beauty, the ability to create it,

or the passion to appreciate it.

The land is not mere descriptive background to our lives,

it is feeding ground, it is the air we breathe, it is inextricably existent with us.

A little rebel thread, never expected,

at first unwelcomed maybe even feared, shows us the way.

An inch of stitch brushing her skin –

the hidden inside, an existence, a proof of life before this moment,

cloth that soaks tears of pain, and also joy.

Stitch of pain, may I see you and come to cherish you;

I slip over the hair and shoulders of my beloved

as a stitch becomes a brooch for my friend and

I wear my story on my sleeve, the stitches of my perseverance.

Healing defies the wound,

my new true north;

should I launch a metaphor that will stay with you, needle?

The thread pulls, connected in vision

so let me translate the truth:

mourning dove, why this sky?

A bump in the road,

the key to open the door into my home;

you touch my arm with yours.

A vision through e-sims and an unreliable but unbreakable connection.

A different, very personal window on Gaza –

so different from the violent reports and images on world news.

Rescue – a word –

for how much fits in this history of love?

Mistake=luck=(mis)chance;

like my friend Martha pointed out, mix up the letters of ‘mistake’ and we find’ a kismet.’

There are no mistakes when so many hearts cry out;

the gift, the pattern is not a mistake –

the mistake left a mark, but it was beautiful anyway.

We are broken, imperfect, beautiful, real;

and hopefully woven with love.

Stitched from a choir of thousands and

from all these roots that remain,

we will rise again.

There is always Hope.

There is always Hope.

#FreePalestine

Thank you for reading this blog post. Compliment it with reading about the first workshop with Shahd Alnaami in February inspired by the theme of libraries & my piece entitled ‘Mother’ that I performed at an Open Mic that Shahd also played a role in.

The post Writing for Gaza – Stories of Resistance of Hope appeared first on Rebecca Stonehill.

June 5, 2025

My piece ‘Mother’ – performed at Norwich Writers Rebel Open Mic

I run Norwich Writers Rebel and every year we hold on an open mic in the Quakers Meeting House. Every time, I go through the customary panic of worrying that not enough people will come (they always do) or that they won’t enjoy it (never the case.) I like to have a mixture of music, poetry and prose and so whilst some of it is curated i.e. I ask a few folk to come along, most of the performers are part of the Norwich Writers Rebel collective or they’ve seen posters around the city and ask for a slot.

I also wanted to add an extra element this time around and asked for my family’s advice on how the audience could participate in some way. We decided to provide everyone with a slip of paper and a pencil or pen beneath their seats. In the introduction, I asked people to write something on the paper that inspired them during the course of the evening or that stood out for them. I read some of these beautiful responses at the end of the night. One person even wrote, I feel more hopeful after this evening.

Here are just a few of the many wonderful words people wrote down:

To weave together the terrible and the wonderful.

I try to nurture the green bird in my heart.

Look for the pockets of Joy.

I’ve always wanted to perform myself but, because there are always a number of people wanting to share their work and it always runs a waitlist, I never do. This time however, I’d felt a piece brewing in my bones for some time before the event and I decided I would share what I’d written. And I feel, also, that it’s a shame to just share that piece once at the open mic without others being able to read it, as I spent quite some time writing it. It was in a piece in three stages, and I asked my close friends Cata and Kim to come up on stage with me to read the first two parts.

It doesn’t really need much of an introduction, as I think the words speak for themselves.

Mother

It is Mother’s Day and I am lying on the ground outside Waterstones with a white sheet draped around me to look like a body bag. My husband is lying next to me and we stick our arms out awkwardly from underneath and clasp hands, reassuringly winding our fingers around one another’s. The latest war on Gaza has been raging for a year and a half and we have come here on this sunny April day to honour the mothers of Palestine who have lost children. Too many mothers. This is surreal. We can hear flyers being handed out above and around us and the footsteps of people walking past us on the street, a strange soundscape of exclamations, support and irritation. I feel exposed, a dead person alive on a city street. I hear one man close to my head tutting before he says ‘Bit much, isn’t it?’ I want to jump up, sheet wrapped around me and stand like a spectre in the street not ravaged by war; where people can shop and walk in safety and cry ‘Yes! It is a bit much that our taxes are killing children in their thousands. It IS a bit much.’ But I don’t. I continue to lie there, hands intertwined with my husband’s, the sensations washing over me of shame at what is happening and relief that today I am dead, but really, I couldn’t be more alive.

I did not expect to become obsessed with a peregrine falcon. I knew that she was sitting on a nest at the top of Norwich Cathedral, but somehow I went from that vague knowledge to having the webcam up on my browser to checking in on her multiple times during the day. Even as I type this, I have her on half the screen, her grey feathers ruffled in the wind and her sharp yellow beak tucked into a wing. Behind her spreads Norwich’s skyline, a tapestry of rooftops, playing fields and church spires. On a number of occasions, I have even found myself checking the webcam before I go to bed, the screen dimmed to nighttime mode and I just stare, marvelling. It is compulsive. On the rare occasions she moves from her position to fly away for food, I see four eggs, smooth as pebbles. I wonder how many other people are watching her.

This is motherhood unlike anything I have seen before, her devotion to these eggs; the way she sits here beneath the pouring rain and fierce sun and gusty winds. That instinct to protect and, in doing so, bring forth new life, is powerful. And then, one hatches, a tiny ball of helpless cotton wool. And then another. If I was transfixed before, it has now climbed to a new level. There is a feeling sometimes that too much tenderness, too much love, will break me, break some hard, protective outer layer. And I am fragile right now – I am not sleeping enough and the echoes of Gaza’s dead rattle relentlessly along the length of my bones. And yes, sometimes watching this peregrine falcon mother has moved me to tears. She helps bring me back to the present. She helps quell the fear and grief that surge through my body. I think, she is instinctively protecting her offspring.

I think, this feeling is so familiar with my own three children.

I think, so many will understand it – this desire to keep one’s children safe.

And yet.

And yet.

And yet.

No matter the ferocity of that instinct, the mothers of 18,000 children in Gaza have been unable to protect their young.

Her name is Shahd Alnaami. I made contact with her last year after reading an article she had written in Al Jazeera about the destruction of Gaza’s libraries. I couldn’t stop reading it, for libraries have shaped me my entire life, ever since I was a small child, wobbling on my bike to the mobile library that stood beside the park, clutching my precious stash of plastic green tickets which I exchanged to be granted portals to different worlds. In the words of Shahd, ‘I have never been out of Gaza before, yet I carry the whole world in my heart.’ I am not her mother. I have three beautiful, brave teenagers I am mother to. But still, I feel a mother’s protectiveness towards her. I often think about Shahd’s own mother and what a wonderful woman she must be to have raised such a kind, compassionate and courageous young woman. I also cannot begin to unpick the grief she must have experienced when Shahd’s thirteen-year-old sister Rahaf was killed in a bombing; how great the desire must be to keep her remaining three children safe and how fragile that must often feel.

So no, I am not Shahd’s mother. Her mother is called Nisreen and she is only ten months younger than me. And not only am I not her mother, but I will probably never know what it means to fear for the lives of my children in that way; of not knowing whether a bomb will come in the night or the clutch of hunger will not be able to free them. When my own children were small, I bought them a book called We are all born free. It was a book in pictures of the points of The Universal Declaration of Human Rights. By showing this to my children, I was saying to them This is how we as humans have a right to live. Don’t accept any less. And yet, pulling this off my bookshelf again recently, I was struck as I turned one beautifully illustrated page after another that for Shahd and the people of Gaza, not a single one of these declarations holds true. Not one. I stop at a page that reads: ‘We all have the right to a good life. Mothers and children and people who are old, unemployed or disabled have the right to be cared for.’ But we are not caring for these mothers and children, for the elderly, unemployed or disabled from a land far from here who we have othered. And we are not questioning the government who funds the manufacturing of the fighter planes and the bombs that will fall from the sky to maim and kill them.

We hear mainly of the human toll in Gaza. But what of the toll on Gaza’s land and ocean and more than human beings? Raw sewage pours into the Mediterranean as marine life chokes in its murky waters. Once-fertile soils are ruined. The land has been stripped bare of trees and Gaza’s animals have not been spared from death, starvation, trauma and disease.

Shahd has no idea how this story will unfold for her, but she keeps looking forwards. ‘There is always hope’ she has said on more than one occasion. ‘There is always hope.’ I do not know what to do. I feel such shame. So I do what a friend does for me: I read to her, short chapter instalments on WhatsApp from a book she’s always wanted to read. She does a tick symbol when she’s listened to that section and then I can read another. It breaks me, this way of communicating with her. It breaks me and it fills me. Sometimes, when she sends me voicenotes, I am struck by the bird song in the background. So yes, the birds still sing in Gaza. As I continue watching a peregrine falcon and her young, it binds me with a young woman from my privileged place of peace to a land of such suffering that I feel myself unstitched, untethered to reality. To humanity. Yet if Shahd has hope, then I, too, must allow hope to infuse my spirit. Let us speak their names. And I will begin with the name of one trying, desperately, courageously to survive: Shahd Alnaami.

It is Mother’s Day. Today, I am dead. But really, I am very much alive.

Thank you for reading this  Compliment it with reading about how the first online writing workshop with Shahd Alnaami went here and do join us for her next online workshop at the end of this month.

Compliment it with reading about how the first online writing workshop with Shahd Alnaami went here and do join us for her next online workshop at the end of this month.

The post My piece ‘Mother’ – performed at Norwich Writers Rebel Open Mic appeared first on Rebecca Stonehill.

June 3, 2025

Little Lindford Library

For my birthday last year, my husband Andy gifted me a ‘little library.’ Along with my 14 year old son Benji, they spent time working on it from repurposed materials and although it arrived just a little late, last week we had our official opening ceremony of the Little Lindford Library (Lindford Road is where we live in Norwich.)

They know me well. This is literally one of the best gifts I could have hoped for. I absolutely adore libraries and have done my entire life. And I am one of those curious breeds who, upon passing a little library on a street, stops to tidy it up and make sure the books are neatly stacked with their spines facing out. Don’t ask me why – I just don’t like unruly books  So imagine, now I have my own little library to tidy and take care of. I made sure before the grand opening that there was a bit of a mix in there – adult fiction, non fiction, teen fiction, middle grade and younger kids. I definitely don’t want the kids to be left out.

So imagine, now I have my own little library to tidy and take care of. I made sure before the grand opening that there was a bit of a mix in there – adult fiction, non fiction, teen fiction, middle grade and younger kids. I definitely don’t want the kids to be left out.

We found a little notebook in which I asked for comments and suggestions, and placed it inside with a pencil.

Day 1 after the ‘grand opening’: Books started to come in. We noticed lots of people stopping and looking, exclaiming, smiling. We chatted to more of our neighbours in one day than we had done in the entire year of living here. I am not exaggerating.

Day 2: Walking on the marshes near our house with my daughter and husband, we were stopped by a lovely smiling lady. ‘Are you the family who have the new book swap?’ After we’d answered in the affirmative, she waxed lyrical for sometime about how wonderful it was; about how the area needed something like this and she was so excited.

Day 3: The notebook started filling with messages of gratitude and appreciation. I couldn’t resist leaving little messages back for people.

Day 4: Somebody left a tin filled with beautiful homemade bookmarks. They wrote in the notebook that they were so delighted at the appearance of a little library in the area that they wanted to contribute in some way.

Wow. I wasn’t expecting all this. It has made me so happy. My bedroom overlooks the street and now, as well as being distracted by the sparrows that dart in and out of the bush opposite, I am also distracted as I sit here teaching my online classes and penning my stories and poems by people stopping, smiling, opening the door.

Benji and Andy

There are so many things that I would like to do with this as libraries are, of course, so much more than homes for books. Even little libraries. First off (when I get round to it), I’d like to set up its own facebook page so it can also function as a community group. Perhaps advertising a skill share? Or giving away surplus produce from the allotment? Any ideas, blog readers? I’d love to know if you have any little libraries in your area and how you’ve interacted with them.

In the meantime, I’m just over the moon. And I’m off to tidy my little library.

Thank you for reading this blog post. Compliment it with my poem about my lifelong love of libraries entitled The Public Library Love Letter & how I once set up a library in Kenya which continues to thrive.

The post Little Lindford Library appeared first on Rebecca Stonehill.

April 30, 2025

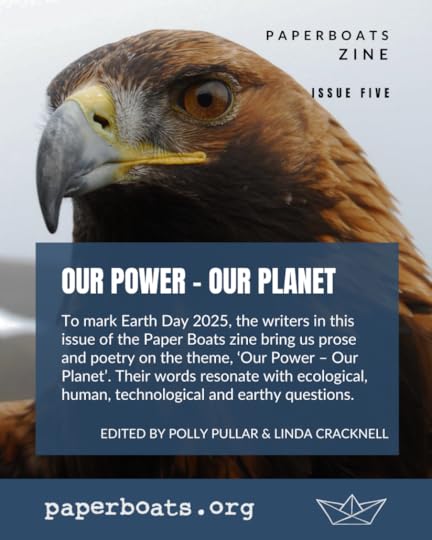

We believe in the future

Paperboats is a Scottish literary zine, formed by a collective of nature writers. The paperboat is a symbol for the current fragile nature of our hopes for climate stability, as well as a campaign tool: over a thousand paperboats have been sent to Scottish MP’s. When they receive one, they will know why and how they must take bold and urgent action for climate and nature. They recently did a call out for poetry or prose for their Earth Day special on the theme of Our Power – Our Planet. You either had to be Scottish to send in work or it had to be based in Scotland. As I’d not long been back from my six week stay on Knoydart, I sat with this for a while, thinking about what element of my trip I could share on this theme.

I decided to write about an unexpected day of tree planting I had been part of, sent in what I’d written, and I was delighted when it was accepted. Click here to read the full poem. Do take the time to read some of the other wonderful contributions also.

Paperboats also has a wonderful podcast, is calling for a fossil fuel non-proliferation treaty and is campaigning for Scotland to become the first Rewilding Nation. It’s a wonderful organisation and I feel really proud to have my work featured in its zine, especially as I’m not a native to this wonderful country north of where I live that occupies a corner of my heart.

Thank you for reading my blog post. Compliment it with reading a couple of poems I had published in journal ‘Dodging the Rain’ in 2024 & a poem I’ve written that has attracted more attention than any other, Lessons in Weariness.

The post We believe in the future appeared first on Rebecca Stonehill.

April 4, 2025

Guest Blog with Ecologist & Writer Helen Baczkowska

‘Loving this Earth and its lives is a political act right now and so writing about it cannot help but be political too.‘

A huge welcome to ecologist and writer Helen Baczkowska who I’ve known for a couple of years through Norwich Writers Rebel. Helen is one of these extraordinary characters who seems to be everywhere, all at once, casting her net wide of activism, campaigning, conflict resolution and defender of the natural world and land access. Whenever I hear of a brilliant talk or event going on in Norfolk around wildlife or environmental campaigning, it’s not an exaggeration to say that Helen is likely to be involved in it. You don’t have to be speaking to her for long to feel her fierce sense of injustice and a strength and resolve that underpins it. It’s definitely infectious.

How long have you been writing for and what kind of writing do you do?

I remember making up stories and poems in my head long before I could write, experimenting with different voices and descriptions, so I guess it is a very innate thing. I also come from a family of storytellers, not official ones, but my Welsh grandparents would tell long stories of their lives and those of their family. For my grandmother, this meant weaving family memories in with Welsh myth and Biblical stories, as if they were all people that she knew.

I have been researching and writing a book on common land in Britain today. An early draft of this and the proposal was shortlisted for the Nan Shepherd Prize. That made me cry. What is amazing is how it goes to the heart of questions over who makes decisions on land today, what the conflicts over land use are and what climate change and pollution are doing to nature. Nearly done and ready to start doing the rounds of publishers.

Please can you tell us a little about what drove you to protest the motorway that was being built through Twyford Down in Hampshire?

As with stories, the roots are deep. My mum used to go to Greenham Common (leaving me at home, much to my early teenage sulkiness!) and I grew up in the midst of the Miner’s Strike, with a family who had worked in mines, so there was a lot of anger, mutual aid and desire to right injustices in my upbringing. Later I became a hunt sab, then, I started a job in Hampshire and saw a poster for a rally on Twyford Down. I went along – it was a May afternoon in the sunshine and the land was alive with flowers, birds, bees, butterflies and tiny spiders in the grass. I thought I could not let harm come to this amazing place without a struggle.

Who or what inspires you and gives you hope?

Nature, always, the people who love it and defend it and the wonderful young folk that I know.

What are you most proud of in your life?

Hmm – pride is something I struggle to feel, as I am only one among many here. I’m glad we were able, collectively, to raise our voices against the Norwich Western Link road and that I was able to bring a lot of past experiences to help.

(ed: for many years, Norfolk County Council were trying to build a 4 stretch mile of road across the ecologically rich Wensum Valley. A group of ecologists, scientists, wildlife-lovers and many more came together to save the valley and after sustained pressure, the scheme has been dropped this year.)

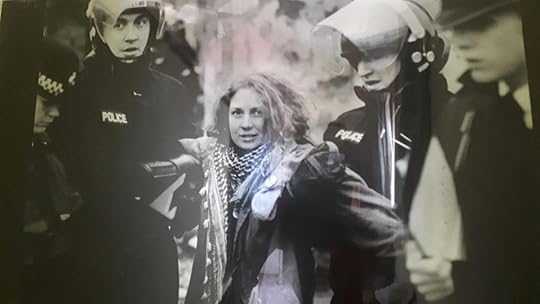

Helen protesting the eviction of houses on the M11 motorway route, 1994. Photo credit M Lambert

Where do you feel most at home?

At home, in the little back room in rural south Norfolk where I write. Or in bed….love bed!

How does your activism inform your writing or vice versa?

I think it is life that informs my writing and my activism is a part of my life. I cannot help but see most things through a political lens, whether it is social injustice or the environment. Loving this Earth and its lives is a political act right now and so writing about it cannot help but be political too.

If you were to press one or two books into the hands of everyone you know and say, you have to read this, what would it be?

Oh goodness, that is a big question! Rebecca Solnit’s Hope in the Dark feels always relevant, the poems of John Clare are always prescient too, and George Eliot’s Middlemarch might not seem like an obvious choice, but it is the most incredibly insightful and rich novel, one that changes the reader.

What work has been the most meaningful to you over the years?

For myself, the work I do on conflict resolution and wellbeing in activist spaces has become one of the most important things in my life. In the future, looking at community resilience feels necessary.

Helen writing nature notes in the Wensum Valley. Photo credit R Long

What feels like one of the most important things people can be doing right now to confront the climate and ecological emergency?

We live in such terrifying times, when protest is so hard and, despite it being at the core of my life for so long, I’m wondering at the sustainability and effectiveness of it right now. So, looking how we create community resilience and take all of learning into those spaces feels necessary – both the counter the rise of the far right and to create truly regenerative ways of living.

This is the start of one of Helen’s book chapters and also forms part of an essay called Growing Clover published in Speculative Nature Writing: an anthology — Guillemot Press

Growing Clover / The Come Alones

If this storm has a name, I’ve forgotten it. For days now, wind has thrown hail and sleet and rain at the ground and I have stayed indoors as the radio told me about famine and war, another chunk of ice sheet melting, another wild creature being wiped out by persecution or habitat loss. Now I too would like to throw something, a thing that would shatter and crash, although the noise, I know, would never be loud enough to make my species stop and reconsider its ways. Instead I huddle into my waterproof and walk down the lane to a footpath along the edge of a field. The trodden mud beside a hedge is all that remains of the Come Alones.

Only my neighbour Harry and I call this path the Come Alones now. He lives next door, in the cottage he grew up in. Once, when I was child, the family’s black gun dog had puppies and I was allowed into the shed to let them squirm, warm and smelling of milk, in my lap. I am not sure how old Harry is, his face is thin behind a white beard and arthritis has aged him. He shifts uneasily when we stand talking and winces as he moves, telling me the pain started when he worked packing frozen chickens in a local factory. As a boy he supplemented his parent’s income by raising goats along the Come Alones. Back then, he says, the path was a narrow grassy track, hedged on both sides. When he told me this, I recalled gathering blackberries with my Grampa, when my grandparents lived in the cottage I now call home. I was eight or nine and we carried the fruit back in saucepans, my fingers and probably my lips, stained with sweet purple juice. The brambles had twisted through tall parallel hedges that were divided by the narrow path of rough grass. The track I remember so clearly can only have been the Come Alones, for although I have looked, there is nowhere like that near here now.

Thank you so much Helen for coming on the blog and for sharing this moving piece of writing. Compliment this blog with reading guest interview with activist and writer Amanda Fox and an interview with solarpunk writerJimJames.

The post Guest Blog with Ecologist & Writer Helen Baczkowska appeared first on Rebecca Stonehill.

Protected: Guest Blog with Ecologist & Writer Helen Baczkowska

This content is password protected. To view it please enter your password below:

Password:

The post Protected: Guest Blog with Ecologist & Writer Helen Baczkowska appeared first on Rebecca Stonehill.

April 1, 2025

Writing Retreat in Knoydart

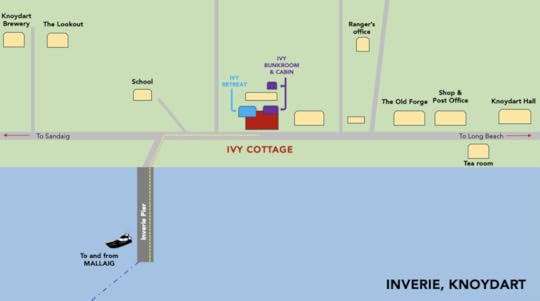

Towards the end of last year I spent six weeks alone in remote Western Scotland writing, reading, swimming, walking, thinking and enjoying a slower pace of life. I decided to stay on after a family holiday with my husband and three teenagers after the October half term. The Knoydart peninsula is often called Britain’s last great wilderness: cut off by the mountains, there is no vehicle access to reach Inverie, the main village there and the only way to arrive is by boat or by walking in which takes 2-3 days.

While I was staying there, autumn gently rolled into winter and brought with it snow drifts and sparkling ice. I built a quiet routine of swimming, reading, pulling on my waterproof trousers and heading out along the coastal path or into the mountains with my binoculars, a thermos of tea, a sandwich and some paper to scribble notes on. My mobile phone also broke while I was there (I dropped it on some rocks whilst taking a photo of a spectacular view and it smashed) and this, I decided, was meant to be. It helped me to sink deeper into the land, the silence and the steady rhythm of the days.

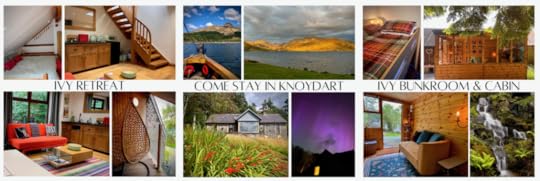

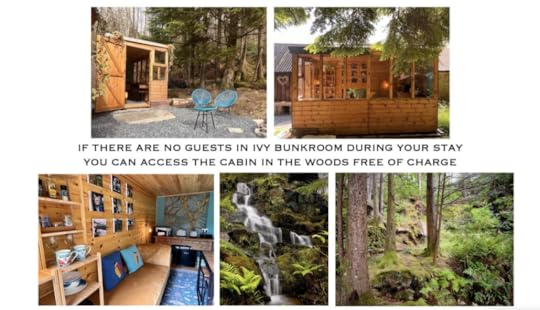

While I was there, I stayed in the cosy annexe of Janey de Nordwall’s home in the heart of the village. Janey is author of the brilliant memoir From a Wonky Path to an Open Road in which she charts her life from film producer to hitting the road in a VW camper van with her cat Kenny, finishing up by chance in Knoydart. She couldn’t have been more welcoming, and is now opening up and offering Ivy Retreat for six weeks for those seeking a quiet space to write over the quieter autumn and winter months. I loved the peace and tranquility of being there off-season with the added benefit of not a midge in sight! There were some really mild autumn days, some glorious sunshine and the peninsula looked stunning covered in a blanket of snow.

Knoydart is such an interesting, inspiring place – last year (2024) marked the 25 year anniversary since the community buyout following years of mismanagement from the former Knoydart Estate. It now has a thriving pub (which often hosts live music, quizzes and other events), a community shop, generates its own renewable electricity through its hydro plant and manages local woodland through the Knoydart Forest Trust. I was really struck by the fact that, even though the population of Knoydart is small (around 110 in Inverie itself and more in other small settlements), there is a strong community sense of people working together and bringing their skills to this wonderful, remote corner of Scotland.

Knoydart is also known for a fascinating slice of resistance and history, where in 1948 the ‘Seven Men of Knoydart’ staked a claim of the land from oppressive landowners and land use for a place to live and work. One of these men was still alive to witness the community buyout.

It is such a special thing to gift ourselves time and space to ourselves and the things we love doing. You could equally go there to paint, or to mountain bike, or whatever it is that fills you. I’d never even heard of Knoydart this time last year, but due to a chance conversation with my neighbour who had recently been there, my interest was piqued and now, looking back, it almost feels like I couldn’t have gone anywhere else.

You can see from this map below how close Ivy Retreat is to the pier where the boat comes in. If you like swimming, even better (I’m pretty sure the locals thought I was a bit bonkers, but once you’ve got the cold swimming bug, that’s it!) The memory of swimming while it was snowing will never, ever leave me.

So, did I get a lot of writing done? I wrote countless poems, journal entries and letters (yes, really, old-fashioned snail mail. So thank you, Knoydart, for having a post office.) And although I didn’t quite start the next novel, which is what I thought I might do, I realised that maybe the next novel wasn’t quite ready for me yet. Composting and reflecting is so important as part of a writer’s process, and I honestly can’t think of a better place for this to happen. I also know deep in my bones that no writing is ever wasted, that every word matters.

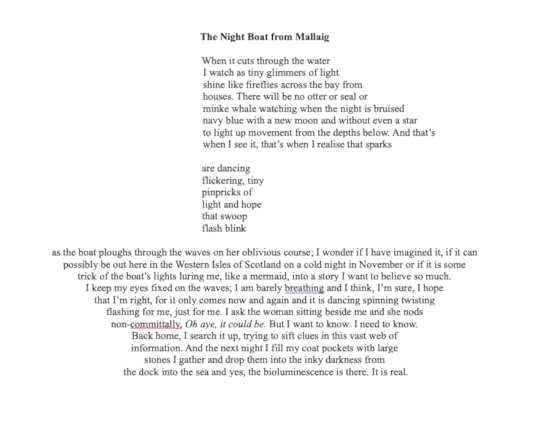

Here is one of the countless poems I wrote while I was there. I don’t very often write poems in shapes, but this was really fun to play around with:

Tempted?

Well, here are a few more photos I took to tempt you a little further. Knoydart is a truly special and unique place, steeped in history and the language of ancient mountains, folklore and wildlife. Maybe it’s time for you to treat yourself and unlock some of the words that are waiting in you.

With my family in front of The Old Forge, Britain’s most remote pub, before they left me for six weeks

Taken from an Instagram post I made after my trip:

Thank you Knoydart.

Thank you for the walks and the swims,

for the deep silence and space,

for a broken phone in the second week

so that I could sink even further into the peace,

for the woodland trails

and coastal roads,

for the day of planting trees and

the weeks of planting unexpected friendships,

for the sunsets and snow,

the flow of mountain burns,

for the hidden work

of minerals, mycelium and microbes

and the deep embrace from land and loch.

The post Writing Retreat in Knoydart appeared first on Rebecca Stonehill.

February 19, 2025

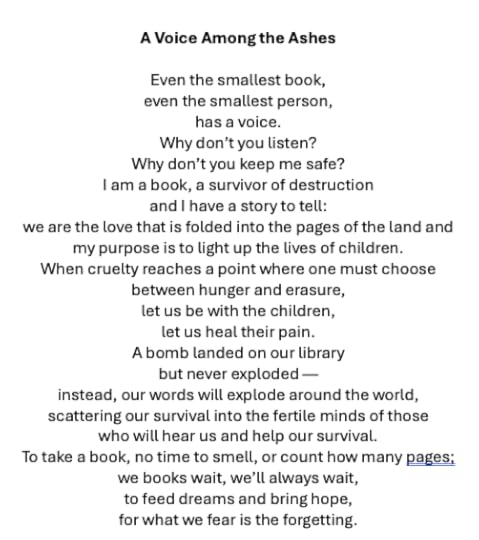

A Voice Among the Ashes

I’ve mentioned before that I run a collective called Norwich Writers Rebel. We are a group of writers of all genres who are exploring the climate emergency with our pens. However, people who are concerned about the climate and ecological emergency tend to also be looking at issues of anti-fascism, anti-racism, anti-colonialism, anti-war. For the past six months or so, I’d been on the hunt for a Palestinian writer who could host an online writing workshop and so our group and many others could stand in solidarity with Palestinians while the genocide raged on across the Gaza Strip and the West Bank.

I had a few false starts, thinking I’d found someone, but then in it proving too complicated and falling through. And then I read this article in Al Jazeera, entitled Gaza’s Libraries will rise from the Ashes, and somehow, instinctively, I knew I’d found my person. Libraries have shaped and defined me throughout the course of my life. They have grounded me, inspired me, given me what I have needed and without a doubt, helped to create Rebecca the Writer. Over the Covid lockdown, feeling acutely their sudden absence in my life, I was moved to write a poem entitled The Public Library Love Letter which you can read here. The point is, here I was reading about somebody else’s love and appreciation for these vital spaces. And yet, unlike during Covid which came to an end and I could walk back through those doors, in Gaza, the United Nations has reported that thirteen public libraries have been badly damaged or destroyed and that many are now being forced to burn books as fuel for fires to stay warm or to cook. In words from the article: This is our heartbreaking reality: survival comes at the cost of cultural and intellectual heritage.

Shahd Alnaami

The writer from the article was called Shahd Alnaami. It said she was a literature and translation student based in Gaza and her passionate advocacy for libraries, reading, writing and literacy shone brightly through her words. It was clear from her article as well that she was a gifted writer. I found her on Instagram and reached out to her and heard straight back.

And so it began, this back and forth of a shared love of books and writing and very slowly, the bare bones of an online workshop began to take place. I constantly marvelled at her Instagram posts, how this young woman was living amongst the hardships of the genocide and so much destruction, and there she was – taking photos of a cloud scudding across a rich blue sky or scribing her words of her prayers and dreams for peace and stability. Shahd is much younger than me (she is 20, not much older than my eldest child), yet I keenly felt with her that our positions could so easily have been reversed. Down to a simple twist of fate, she was born in Gaza and I was born in London. But there we were, two bookish writers from different lands and different generations, just trying to make a difference with our pens.

Credit to Andy South @imagineyouwereborningaza – Andy has been placing stickers and spray-paint art all over the place, just asking us to pause in our day and really consider this

Before Christmas I received the devastating news that Shahd’s beloved sister had been killed in a bombing. Her name was Rahaf and she was 13 years old. Rahaf was bright and curious, a young teenager who loved drawing and singing and couldn’t wait for the day she would see a ceasefire. That day did not come for her. So much needless death; so much needless suffering.

Rahaf

And though a ceasefire has now been declared, with President Trump’s vows to turn the strip into the ‘Riviera of the Middle East’ and the offensive ramping up in the West Bank while all eyes are on Gaza, this ‘ceasefire’ is far from secure. I thought that it would be too much, given her heartbreaking circumstances, for Shahd to now run the workshop. But after a while, I heard back from her. I want to do it still, she said. A still, calm voice of extraordinary courage.

And so, on the 9th February, on a Sunday afternoon following all our preparations, we held this online workshop. We had people on the call from the UK, the US, Canada, the Netherlands and Gaza itself. Shahd had literally just completed her exams and was having to walk long distances to sit them and also huge amounts of time and perseverance to gather the material for two short videos she wanted to share for the event, which she used as springboards for the writing exercises.

Shahd had never taught in this way before but she was a natural and stepped into this space with so much wisdom and courage. I was in awe of her; everyone in that workshop was. The collective solidarity and energy in the space was palpable, even from our different little boxes on the screen and when I put my laptop down at the end of it, I knew that Shahd’s was a voice that the world needed to hear.

A destroyed library in Gaza

I have now set up a fundraiser through GoFundMe to help re-build and re-stock Gaza’s destroyed libraries. You may think, why donate money to books when people are starving and need food and medical treatment? And it’s true that first and foremost sustenance needs must be met. But books can heal, words can heal, stories can and do heal. In fact, I firmly believe that telling better stories will heal our world.

Half of the money from this fundraiser will go towards re-stocking and re-building Gaza’s libraries and the other half will go to Shahd, her family and her friends. Having lost two homes, she is currently living in the roof space of her uncle’s house. Despite all this, she is continuing to study (although this is online as her University is no longer standing) and to write. One of the projects that she wants to donate her own portion of this money to is the work of her aforementioned friend, Hani Alsalmi.

At the end of the workshop, I asked everyone to type in a word or phrase from some of the writing they had done over the course of the two hours. In the following days, Shahd and I wove these words and images into a group poem, which she entitled A Voice Among the Ashes. Here it is. I hope you enjoy it. And do please consider donating to and sharing this fundraiser. Thank you

NB Everything I have shared in this post is by generous permission from Shahd Alnaami. Follow her on Instragram @palestinian.shahd

The post A Voice Among the Ashes appeared first on Rebecca Stonehill.

February 5, 2025

Solarpunk: Creating the future by imagining it

‘There’s millions of people, peopling out there, every day. It’s hard not to be inspired by that.’

‘…you create the future by imagining it.’

‘We have the requisite amount of goodness to do what needs to be done.’

A big welcome today to James Graham, better known as JimJames, who has come to writing more recently. I know JimJames through activism circles and Norwich Writers Rebel, the collective of writers I set up a few years ago, bringing people together who are exploring the climate and ecological emergency in their writing. Whenever there is a drumming event with Extinction Rebellion, he is always to be seen putting his heart and soul into this craft, something he is now also doing with his writing. Solarpunk as a genre is not something I am very familiar with. If you, too, don’t know much about it then read on and find out about JimJames and the new worlds he is weaving with his writing.

Welcome JimJames. Can you talk about how and why you got into writing and what Solarpunk is?

It’s difficult to say what ‘got into writing’ means for me at this point. Part of me has always wanted to do this, or expected that I would someday. I remember having writing pretensions when I was young but more recently, I decided that one of the things that was missing from the discourse around climate change and transition in the activist sphere more generally was any idea that the future was ever going to be pleasant or that we were going to find niches of joy and do the things that people do all the time, even when times are hard. I know some of that is a deficit mindset where we look at problems because there are problems and we assume the rest will sort itself out. That’s fine, but you create the future by imagining it. We start by thinking about what it’s going to be and how it will work and I just didn’t see a lot of that happening.

Countering it was this wave of doomy, cynical, smartest-guy-in-the-room, and frankly, deeply boring rhetoric about how It’s all just screwed, and Don’t worry with this activism and Stop doing it, it’s all pointless anyway. This is the only thing that really makes me angry these days. I just keep wanting to scream in these people’s face No! Fuck you and your edgy bullshit. I want to live! If we can. I want my people to be happy and find their place and joy and do things that matter to them. Solarpunk for me is exactly that mentality. It has a reputation as being comfortable and soft, and that’s fair, but the point is that it’s doing it because life’s hard, and it’s important that we embrace the small comforts.

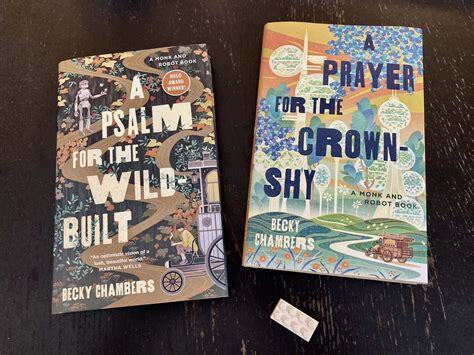

The Robot and Monk novellas are quintessential Solarpunk reads, a bit like taking MDMA or having a good solid hug or warm bath, but don’t lack peril or drama for it. I think that’s important that you can have fiction like that, but I want people to be telling stories like that about this world. It gets called Hopepunk or hopium much more often I and don’t like that. A lot of the attempts at climate fiction I’ve seen aren’t very good at ‘staying with the trouble’, they tend to create narratives that either pretend problems aren’t important or they fixate on one particular problem to solve. I want to be able to tell the story where it all turned out okay, but it’s credibly grounded in reality. A story that’s talking about technology and ideas and principles that already exist so we don’t have to have magic.Some cool new technology for sure, but mostly stuff that already exists and it’s important to me that somebody is doing that. I will not say for a second that that person should be me, but not enough people are doing it and I do have the kind of professional background to be able to talk credibly about this, and make it feel real for people.

In an ideal world, what would you like to see happen with your writing?

In an ideal world, I would love to see millions of people read the story and be inspired to spark gentle little revolutions and send me lots of money so I can write more of them. That would be wonderful, but I will settle for reminding people that even in the worst of times, even during the actual real-time end of the world, they are allowed to find comfort and joy in simple things and that will happen. I don’t think we talk about it enough, not in this useless economy.

The very basic idea of my book is just tracing a credible, albeit not terribly likely, story of how we get from here to being okay through all the problems. It’s a project of packing as many good ideas as I can possibly think of that we could use to solve big and small problems into one thing and if a few people come away with those ideas, and enjoy how they fit together and feed each other, I’m happy. If a few people come away from reading it thinking That was cool idea, I’ll look up that or I could totally do that at home or Yeah I want to be that guy, that sounds like a good job I could do and then they look them up and realise they already exist, that’s cool. This may sound a bit lame, but I’d like to inspire people. I think the point is it’s inspiring but with a grounding in actual reality; inspiring from now rather than hoping for something better to happen later.

Can you name one or two of your favourite books of all time and why they’re so important to you?

Quite a lot of my favourite books, certainly some of the better books I’ve read until very very recently were kind of Grimdark Sci-Fi. That’s probably partly where I’ve turned to the opposite in that I got tired of the people attracted to the misery thinking they were doing something clever, when despair feels like rest now. I got tired of being that guy.

I like a bit of dark on occasion but as counterpoint.

When people ask for my favorite books now I tend to use it as a way to expose them to literature that I think is good rather than the ones I remember enjoying. The answer to that question is the Robot/Monk series or basically anything by Becky Chambers. The other books that I’ve read and now have bought physical copies to be able to hand to other people are HumanKind by Rutger Bregman and Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer, just because those were the two best examples of books I can think of that made me think differently and really ‘blew my mind.’ My worldview changed as a result; they’re challenging in a way that makes you think better of people, not worse. Again, I think that’s something that we need more of now.

The book that I’ve actually based mine on is called World War Z and it’s a ‘speculative oral history about the Zombie War’ which, although not particularly high brow, it feeds something in me that wants to know how people respond to things. By training, I’m a social scientist. I think about systems and how systems change and that’s what I want to read/write about. Zombie media is all about how people deal with stress and I want to write a story about how people manage that in a positive way. Where things get better rather than How do people deal with stress the way and simply survive? Which is what a lot of climate fiction does.

What are you most proud of?

I have never really thought of myself for someone with very grand ambitions. That is perhaps somewhat ironic for one who, when people ask what they do for a living says, “Trying to save the world, Pinky”. That’s also perhaps an odd thing to say as someone who is now embarking on what is going to be quite a large and complex writing project as their first serious work. But I am reminded of Kingdom of Heaven, which is a slightly pretentious medieval epic but has many lines that’ve stayed with me:

‘By what you do every day, you will be a good man, or not.’

I think that is important to me more now than I realized, along with another line from the same:

‘What man is a man that does not make the world better?’

I am aware of how pretentious this is going to sound but I’m proud of my life and what I spend my time doing. Maybe that’s not every day but most days. I’ve built a life where I’m comfortably living in the trenches of climate action/strategy and telling stories about the next world. At least, this is what I’m happiest being proud of. It’s not strictly an achievement or a milestone but there’s been lots of them and when they’re over, it’s always onto the next, the what I do every day.

Who or what inspires you the most?

Here’s a quote from Paul Hawken of Project Drawdown:

When asked if I’m pessimistic or optimistic, my answer is: If you look at the science about what is happening on earth and you aren’t pessimistic, you don’t understand data. But, if you meet the people working to restore the earth and the lives of the poor and you aren’t optimistic, you haven’t got a pulse. What I see in the world are ordinary people willing to confront despair, power, and incalculable odds in order to restore grace, justice, and beauty to the world.

Responding to that question with someone else’s words feels cheap but that is it. I have worked for many years in climate science, system change and activist spaces and at every turn I am confronted with beautiful people working so hard with almost no hope left in spaces that require them to be so careful and gentle with each other and they don’t stop. And they’re not alone! There’s millions of people, peopling out there, every day! It’s hard not to be inspired by that. I think going back to the book, the core and to an extent the core of Solarpunk more generally is that people, peopling, will solve the problem. Perhaps not solve it, but it can be enough to make the future better, to get us where we need to go. If we establish the focus of our society as ‘people peopling’, I think we might be ok.

Where is your favourite place in the world?

I think my home, my house. I’m sorry that’s not more interesting, but I am glad that the place I am most comfortable and feel safest in is where I spend most of my time. There’s a slightly more temporal answer to that question in the sense that the favourite place I have ever been is in London for the Rebellions. Even though that was time in a very particular construction of circumstances, but those were the places around London where I felt most happy and purposeful and at peace, I think. Very often tired and sweaty and dirty and sad at the same time. I constantly wonder what it would take for life to be like that every day. I think that would be my ideal. Possibly not under the specific circumstances of the impending apocalypse and police, but that feeling of purposeful community and having something to do all the time and being surrounded by wonderful people that you love regardless of whether you know them or not doesn’t feel like a bad blueprint for a society.

What gives you hope?

Honestly, not a lot. I long ago developed what I described as ‘an allergy to good news’. I don’t know exactly when it happened, but it was sometime around the Masters when I was doing green technology and sustainability politics. When you understand, when you look at the whole scope of the unfolding disaster around us, every step forward just reminds me of every of how far we have left to go. Whereas every time Musk or Trump doesn’t something so ridiculous it’s just funny because against the backdrop of utter unfolding disaster, what’s one more clown? But, every time we take a step forward I think Oh god, now I’ve got to do the work. By the same token, I think it’s important to not let that feeling make one cynical. I don’t think I would have survived this long. I think ‘qualified optimism’ is the term. We could even call it ‘studied naivety’ if you wanted to, I think. Very simply, we have all the tools we need. We have all the ideas. We have the requisite amount of goodness to do what needs to be done. That reality, confronted with the still-ongoing apocalypse is very frustrating but it’s so easy to fall back on when things get really bleak. I remember that we absolutely can have nice things and we absolutely can do better.

For others wanting to write but who lack confidence or don’t know where to start, what would you say to them?

At this point, I’d ask them for tips. I think I’d want to sit them down with a coffee and ask about their project to get me excited about it because that’s what I want someone to do for me. Time to bounce ideas off someone. I have no pretence at being a writer at this point. I have written, currently, the plan for a very long book, some of the first chapter and a couple of short stories within the setting.

To answer the question: I know the advice that I’d be given by absolutely everyone is ‘Just start’. Do something and do a little bit every day if rhythm is what you do well, but if not find those moments when you are struck by inspiration: write something then. Then when you smoosh it into something bigger, it’ll be crap and then you can edit it into something better and then you can hand it to someone who knows what they’re doing, then it’ll be even sharper. You can throw it at all your friends and they’ll be nice about it, probably, because that’s what friends tend to do. I take great comfort in the fragility of some of the people who end up being in charge of things. If they could do that with such confidence, then you can knock it out of the park, so get on with it. I believe in you at least as much as they believe in them.

Humberside

As we passed the Goole our bow wave danced and jumped through between the ruins. The plants that grew over the old walls lapped and waved. We followed the old highway as it rose out of the water and ran alongside us towards Snaith. The land beside the highway grew greener as the salt water released its poisonous grip.

We’d left the homeship in Cleethorpes Harbour and taken the smaller skiff inland while flights of cargo drones whizzed overhead. Sure, they were annoying, but there was no way we’d be able to deliver all that food and material by hand. Our job was handing off the resettlers to their negotiated landing places. The world was on the move, everyone knew it, but here, today, the Boonmees had travelled across the crumbling world, but they had been chosen to live here, welcomed and needed for their expertise and experience with salt water inundation and coastal defence.

As we approached Snaith, there was a gaggle of people waiting on the jetty. The encroaching saltmarsh tickled the underside of the reclaimed wooden and plastic panels that had grown out from an old concrete railway siding. The storm last night had blown in one of the floating solar arrays. The little island bumped up against the edge of the saltmarsh while an opportunistic maintenance crew traced cabling through the mattered plant life to ensure everything was in order. We could see flickers of fish scudding into the estuary from their disturbed nurseries on the underside.

There were cheers, greetings, offers of food with beer, and the predictable requests for news as the six of us landed on the jetty. We followed the throng up Ferry lane and into the town proper. This close to the water’s edge, most of the buildings had been mined out, ready to become a breaker reef like Goole with their useful innards being transferred further inland to provide resources for the rest of the town. Urban mining wasn’t just the domain of the neomad wrecker clans, everyone in town played their part in stripping out buildings before damp mulched them down to poison the ground. The salt scent of the sea receded, replaced with petrichor as we emerged into the ruderal cracked crossroads that served as the central gathering place in town. The old Plough Inn slumped, tired on the other side.

Mok Boonmee was already engrossed in conversation about what species of plants he’d brought with him to be germinated in Snaith’s salt marsh, and I took it upon myself to introduce his young’uns to their new lodging at the Inn. They were delighted to find their rooms fitted out with everything young people would need to acclimatise to a new place. The townsfolk had donated everything. It was always a surprise to find how welcoming people could be, and how generous. It was why I always insisted on coming ashore and meeting them first hand. As we crossed from cosy dimness into the brightness of the crossroads, the sound of tabla, violin, many stamping feet vibrated the air as voices rang out in grateful welcome.

Thank you so much JimJames for coming on my blog and keep going with your brilliant Solarpunk tales to help breathe new perspectives into future narratives mired in dystopian doom. Please keep us posted how you get on.