staying alive

TRIGGER WARNING: death and disease.

A few winters ago, my now-dead baby sister hit her threshold when the shitty cancer she had seeped into her spine. Pain that had been manageable took a turn, and her oncologist directed her to seek admission to the hospital. She lived in a small town sixty miles from Manhattan. I was flying in from Portland as her condition escalated. By the time I arrived at her rural farmhouse, her husband was warming up the car for the drive. It was around 6:00 p.m.

From the backseat I tried to comfort, but her pain was a ten, and she could barely eke out a moan, despite the oxy she’d taken.

We knew from the outset that there were no empty beds on Oncology, and the doctor told us the only way to be admitted was to go through the ER. “They should have a bed for her within a couple hours,” he assured us.

What followed was a long, drawn out nightmare.

There was no pandemic, no national emergency, just a regular winter night at a big city hospital. A big city hospital named “top five” in the nation, no less.

I followed my sister’s husband as he wheeled her into a closet-sized cubicle that already held a patient—an elderly woman moaning and groaning. There was no curtain or anything separating us, as this cube was made for one. We helped my sister onto a tiny bench-type “cot” and managed to find a chair to wedge in next to her. Her husband and I took turns sitting in the wheelchair and the proper chair, and for several hours we tried to comfort her while we watched the hustle and bustle of critically ill people and an overtaxed staff attempting to administer emergency treatment.

“Why are you here?” said a nurse, eventually.

“The doctor said…” my sister’s husband began.

“That this was the way in to an over-census hospital?” said the nurse, rolling her eyes.

Apparently, the ER hates when doctors employ this work-around, and they don’t even try to hide their disdain. Also, it’s very, very common.

Hours passed. A man with a pus-oozing leg triple the size of his other leg, sat on a gurney just outside our doubled-up cubicle. The nurses knew this guy by name. He was a regular customer. He kept begging for pain meds; a frequent flyer, people like him are called. The groaning lady in the next cot was basically ignored.

After a few hours, a hospitalist doctor peeked in and asked to get up to speed on my sister’s case. Her husband has a steel-trap mind for details, and articulated all the values and data and drug info while the doc nodded and promised she’d have a bed “shortly.”

Fast-forward to four a.m.

The after-bar crowd arrives with their cuts, bruises, barfing.

No bed at the inn, still. My sister’s pain unabated. No IV morphine administered.

I decided to go for a walk. Get some food for my sister and her husband (though my ninety-pound sister was in too much pain to eat). It was snowing outside. My phone claimed there was an open McDonalds a few blocks away, so I zombie-walked to the fast food spot for a few sausage biscuits and troughs of coffee. The shock of having a healthy, relatively young family member suddenly come down with a fatal illness has a surreal quality. The ground not really being the ground. Similar to a 4:00 a.m. walk through uncharted urban territory in the snow. Add to that the experience of being met with an over-taxed medical environment that can do little more than placate with vague promises, and it’s a recipe for despair. But still, I summoned faith. Surely, I thought, my sister’s bed would open by dawn.

Of course there was no “bed” by dawn. The only way there would be was for a patient to “expire” or be discharged. Discharge orders aren’t typically given until after morning rounds. It’s a numbers thing. The numbers are finite. After eighteen hours in an overstuffed big-city ER during “normal” times, my sister finally was admitted to the top-notch hospital. Was finally given appropriate relief for her pain and attention to her spiraling disease. She died eleven months later, and I wish I could say that her illness was met with unfailing competence and care. The insurance red tape alone an obstacle no critically-ill person should have to confront.

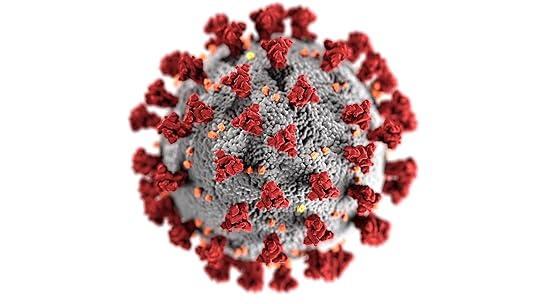

As I type this, Sunday, March 15th, I’ve learned that at this moment there are 269 positive COVID-19 cases in NYC. ICU beds are currently at 80% capacity.

Stay home, folks. Cancel that bellini brunch. Limit exposure. Keep a distance. Save lives. Do your part.