Why I Am Not An Evangelical Anymore

At some point we all have to answer the question, “Who am I?” Who am I, apart from who I have been told I am supposed to be by my family, my friends, and my community? And then we have to come to grips with the fact that some people won’t be pleased with our answer.

In the last year my answer to that question has changed dramatically, and it has changed in ways that I know have been uncomfortable and even painful for those around me. It has been uncomfortable and painful for me too.

This year I left evangelicalism, and I know I’ve left for good.  The funny thing about leaving evangelicalism is that many of your fellow evangelicals aren’t quite sure what it means when you say, “I’m not an evangelical anymore.” Evangelical isn’t a term we use in our day-to-day conversation, and I’m not sure I even understood it until I was leaving it. I think this is because we just call ourselves “Christians,” or “born-again Christians,” and we all know what we mean when we say this. We mean Christians who are like us, Christians who believe the Bible is the authoritative source for how to live our lives, who have what we consider an “active” relationship with Jesus, and are heavily invested in sharing our faith with others.

The funny thing about leaving evangelicalism is that many of your fellow evangelicals aren’t quite sure what it means when you say, “I’m not an evangelical anymore.” Evangelical isn’t a term we use in our day-to-day conversation, and I’m not sure I even understood it until I was leaving it. I think this is because we just call ourselves “Christians,” or “born-again Christians,” and we all know what we mean when we say this. We mean Christians who are like us, Christians who believe the Bible is the authoritative source for how to live our lives, who have what we consider an “active” relationship with Jesus, and are heavily invested in sharing our faith with others.

We can recognize these Christians by the way they talk about their neighbors (as people they’re hoping to tell about the Gospel), the Bible (should be read daily and to answer any questions), and God (as our father and best friend who we talk to regularly). I don’t say this to mock. These Christians are so good at building community and constructing a narrative for a meaningful, purpose-driven life. Often they are incredibly generous to their communities and friends, genuinely yearning to see the best for those around them–whether that means providing them with a place to stay when they need it, directing them to the Scripture that best addresses their problem, or telling them about a Jesus who can save them both from a life of emptiness and eternal separation from God.

This isn’t always the case, of course–there are plenty of churches that are hypocritical, shallow, and internally-focused rather than focused on serving their communities. There are plenty of Christians who are self-righteous and manipulative and even abusive. And while I have witnessed that, I have also witnessed the good side of this kind of Christianity. I have been loved well by my college ministries and by many evangelicals in my life, from homeschool moms to church friends to roommates and family. This is the community that supported and championed me as I went off on missions trips and on academic programs. They prayed over me when I felt anxious and alone and walked with me through heartache. They have, in countless ways, shaped me into who I am today.

But who I am is not, and can no longer be, an evangelical.

This is becoming a pretty frequent cry these days, particularly among the younger generation. Many of us are tired of hypocrisy, especially when it comes to politics. We don’t understand how it was white evangelicals who elected a blatantly immoral and arrogantly uninformed president. We don’t understand how our churches are not crying for justice for immigrants, refugees, and victims of gun violence. We don’t understand how the church can turn its back on the earth God gave us to steward well. We don’t understand how the community that raised us can continue to ignore and even deny science, racism, economic inequality, sexism, homophobia, the wisdom of academic institutions and experts, and the sea of ongoing injustices and inequalities in our society.

Yet while I understand this frustration and echo it, this is not the main reason I left evangelicalism. I don’t believe evangelicalism in its essence has much to do with conservative politics; they have simply been bound together through a complex and unique history, particularly in the United States.

No, I left evangelicalism for theological reasons. I left evangelicalism because I no longer believed the central theological tenets, which are as follows:

The Bible is the authoritative, inerrant Word of God.

One must be “saved”–that is, choose to believe that Jesus is the son of God and their Savior, a choice often accompanied by dramatic life change–to avoid eternal punishment and to live a fulfilling life.

Christians, thus, must try to get other people to believe in Jesus so they can be saved too.

In evangelical Christianity, this is considered good news–in fact, that’s what the word “Gospel” means: good news. It is good news that God gave us a book in which we can find the answers to our questions and hear his voice. It is good news that he sent his son Jesus to a gruesome death, in order to save us from our depravity and the despair of hell. It is this good news that we must share with others: You are inherently wicked and thus must be saved from hell; I have a God who endured your punishment on your behalf, and all you have to do is believe He did it.

There are ways to phrase this that feel more palatable as good news. Perhaps hell isn’t a fiery place of eternal torture, but simply a place where God is not present, or a state of nonexistence. When faced with any of those options, an eternal life of bliss in heaven certainly would be good news.

But many problems remain: Why would a good God take out his anger about sin on his son in such a brutal way? Do I really believe my friends and neighbors who don’t believe in Jesus deserve such a brutal death or eternal torture? What about the many ways the Bible doesn’t line up with history or science, or the many texts within it that contradict each other?

Evangelicals have an entire system of answering these questions, called apologetics: the defense of the Christian (read: evangelical) faith. These answers are aimed at explaining away the tricky questions that pull at our conscience–questions about our friends going to hell or other unjust suffering–by finding ways to justify it, to explain how those tragedies really are just according to God, despite how unjust they feel to us. We especially have to defend the Bible’s authority and accuracy because if we can’t trust that, the faith we have built on all our careful, systematic answers and biblical interpretations falls apart.

I took apologetics as a course in high school, asked the questions with many Christian friends and leaders, answered the questions for my non-believing friends, and became an evangelical leader myself–in college ministries and on missions trips and in Bible studies I hosted in my dorm room. I was absolutely committed to my evangelistic goals and my faith, doing everything I could to bolster it: leading and attending Bible studies, prayer meetings, worship nights, church services, and my own quiet times with the Lord.

But even though I knew I could frame the Gospel in a way that seemed to avoid or cover up the uncomfortable parts (and, when asked, could simply say, “God is too big and mysterious for us to understand” or “God’s ways are higher than our ways”), the questions were still there, growing bigger and bigger all the time.

To me, it seemed grossly unjust that anyone who didn’t believe Jesus was the son of God would be punished eternally for it. There could be any number of reasons not to believe in Jesus, including: having never heard about him, having only seen him poorly represented in the church, growing up in a different religion, and having intellectual disagreements with the Christian faith (which I secretly shared).

And as much as I could quibble about what “eternal punishment” meant, ultimately it all came down to one dividing line: Did you believe Jesus was the son of God, the Lord and Savior of your life, and the Messiah of the world–or not?

If you did, you were “in”; if you weren’t, you were “out,” and it was our responsibility to do everything we could to get you in. Which turned out to be a real inhibitor to interfaith conversations, as I discovered when I joined the Jewish Studies program at my college, ended up working in state-wide Jewish programming, and ultimately lived in Israel for five months. It also came with deep ethical issues, especially in the Jewish community: was it right to try to evangelize someone who was actively involved in another faith? What if they seemed deeply satisfied in their faith, despite the fact that I was told only Christians could be really, truly satisfied? What about the longstanding history of Christian persecution of Jews, leading to some very legitimate distrust today?

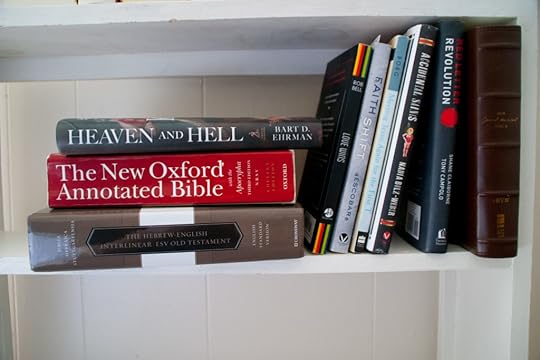

I knew all the right arguments to justify my beliefs and actions, but it didn’t sit right with my soul anymore. And after three and a half years of college and religious studies, I could no longer read the Bible as I had before. I could no longer turn my back on scientific consensus on evolution and climate change, on archaeological evidence that contradicted biblical records, on the work of historical-critical biblical scholars who had good evidence that these texts were often written hundreds of years after the events described, and usually for contemporary political agendas rather than to give me, a 21st-century reader, a solid understanding of history and science and how to navigate today’s questions of gender roles and my own anxiety about the future.

Most of all, I could no longer turn my back on the texts themselves: texts that often offered multiple theological viewpoints on the same issue, were opaque rather than clear, and did not contain the straightforward messages I had always been told they had, messages about salvation, the afterlife, the end times, and the purpose of my faith overall. It seemed the Bible–the Gospels and the Prophets in particular–were much more about justice for the oppressed and real-life change on this earth, here and now, than I’d ever realized, and had very little (if anything) to do with staying out of hell. That, to me, seemed a far better “good news” than the one I’d been given.

Yet as the reasons to leave piled higher and higher, I was terrified. Would I lose my community? What answers would help me navigate the world? Could I still be a Christian? Was I going down a wrong path headed away from God, or even for eternal damnation? I knew that was what my friends and family must be thinking, and yet I couldn’t stop.

I knew if I continued to believe what I had always believed, I would not only be denying the intellectual, ethical, political, and biblical evidence in front of me, but also the voice inside me that told me what was right. My conscience, my soul, cried out that it was wrong to separate people into these categories, it was wrong to go into relationships with the agenda of conversion, it was wrong to defend a God who sent good and loving people to hell for not believing what I believed.

I had been told that my heart and emotions were deceitful and I ought to hold onto my evangelical faith above all things; that the Bible was higher than human intellect. But it turns out, to keep living like that would have been to live in opposition to the things I actually believe, to my intellect, and to my experience of who God is. So I left.

I know, for many, this won’t be a good enough reason. I know there are lots of answers and explanations and alternative frameworks for many of the issues I have just raised. But for me, this is no longer a question of whether there is a good enough answer to justify the things I was raised to believe. I do not believe them anymore. I cannot.

This has put a great strain on my relationships with family and friends, and has meant the loss of some communities that were important to me. Even though those are communities full of kind, loving people, I know I could not go back and be fully honest about what I believe now. I would be an outsider, someone who went down the wrong path and abandoned the truth. I would threaten people’s core beliefs and make them feel rejected and betrayed. I would not be welcomed into positions of leadership. I would not count as a “Christian.”

And yet I think there is a way forward for me in Christianity still. This Christianity is much less clear, and I have few certain answers. Yet for the first time I do not have to shut out my mind and my heart to believe the “right” thing. I can wrestle with the Bible, understanding it in its context, listening to the many and varied voices, agreeing with some and challenging others. I can bring my experience of God and not just the God of the Bible to the table, a wide-open table surrounded by people of different religions, nationalities, and sexual orientations, all doing our best to understand who God is and who we are. I can fully engage my love for scholarship and embrace my sense of justice and desire for inclusivity, even–and especially–in shaping my theology.

The many and varied texts that make up the Bible compel me; biblical scholarship has opened them up for me in new, surprising ways that give me hope for my faith and the future. As my old methods of biblical interpretation have fallen away, I have found that God is not who I thought he was: he is far better.

I am still not sure exactly what I believe, but I will continue to write about these things because they matter. Our religious communities matter; they give us connection and purpose and family; they help us become better people and serve our world. Our beliefs should make us better neighbors, better citizens, better friends.

I still believe in a world that is better than this one. I believe that humans are meant for more than this, that we have a deeper value than our biological existence alone can explain. I still believe in forever.

And I want with everything that is in me to believe in a God of justice, a God who promises to make things right, a God who is not interested in vindictive punishment, but in overturning systems of injustice and oppression and restoring every suffering person–and this entire, beautiful earth we live on–to wholeness.

If there is a Christianity I believe in, it is that one.

—

Postscript:

To everyone who ever felt that I was trying to change them, to make them a Christian, or was doing anything less than fully loving and accepting them as they were: I am so deeply sorry. I have no real answers for you anymore, but I realize now that’s probably not what you were looking for anyway.

To everyone who perhaps feels, as I described, hurt or threatened or rejected in reading this: I’m sorry. I know this is hard stuff. I hate that me leaving also makes people feel left behind. Please know that my intention is not to convince you that you’re wrong, but simply to say that I left and give a reasonable explanation for doing so. I hope doing this will help me to live a little more honestly in the world.

To anyone who maybe feels a little bit of hope that they aren’t alone and that there are more answers than the ones you’ve been given: I believe in this for you. You can have it too. It will be a long, hard journey, but it is so worth it to be fully and finally honest with yourself, and to, maybe, discover a faith that actually feels like good news.