The Ghost of Esmerelda

One of the disadvantages of being a late addition to my family is that I never met any of my grandparents. None of them survived into old age and so they were all gone by the time I was born. They weren’t talked about much—in fact I don’t ever recall my father saying anything about his childhood—and as my parents had moved many miles from their roots, there was barely any connection to this earlier generation; just a few black and white photos. These were kept in a bureau drawer, jumbled in with all kinds of other things and I’d occasionally open it and see my mother’s parents. Her father, Ernest, beamed, almost bursting out of his waistcoat with bonhomie while her mother, Hilda, stared at the camera, neither friendly nor severe, giving nothing away. Their world of London pubs, the Blitz, and masonic dinners was a long way from mine and I looked on them as a curiosity from another age.

It was only after I had my children that I wished for more connection to my family history. After all, if you grow up knowing your grandparents, there’s a reasonable chance they might tell you stories about their parents and even grandparents, scooping you up in a continuity going back several generations, and providing a sense of where you come from. There was none of that in my family. I didn’t even know where my grandparents were born.

By the time I’d become curious about this, my parents were dead and like so many of us, I regretted not having asked questions while I had the chance. So I took out a subscription to Ancestry and began to excavate my family history, starting with my maternal grandmother, the inscrutable Hilda. I was by then a harassed mother of four and as I was always in a rush, I was amused to recall one of the few childhood stories my mother told. Hilda would make elaborate party dresses but she always ran out of time, and so my mother and her sister would have to be pinned into their new clothes at the last minute. Many a party was spoiled by silent torture from invisible pins. Fortunately for my children, I don’t sew but I’m definitely of a slapdash, last-minute persuasion. It may have been a tenuous connection to my grandmother but it was better than nothing and I treasured it.

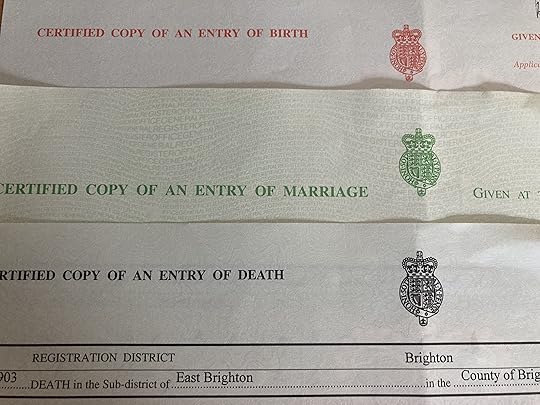

I searched online for birth, marriage and death certificates, as well as census entries and as I did so, I became increasingly perplexed by Hilda. Not only was she inscrutable but she was also proving to be extremely elusive. It took a while to work out what was going on, but eventually I uncovered a trail of secrets and false information. I think my mother would have been surprised to discover that Hilda was really named Esmerelda and that she was quite a few years older than she claimed to be. On the other hand, maybe those things are not that unusual; people are often coy about their age, and it’s not uncommon to go by another name. But I do think my mother would have been amazed to find out that Hilda was already married when she met my grandfather. And I think she would have been absolutely astounded to discover that Hilda had four children from this first marriage. When she fled to London in 1919, newly-divorced and leaving no forwarding address, she took her youngest child Winifred with her but left a boy and girl behind in Brighton. There had been another little girl, Phyllis, but she had died several years before from gastroenteritis. By the time she ran away with Ernest, Hilda was already pregnant with my mother, and they later had two more boys. So although my mother went through her whole life thinking she was the second of four children she was in fact, the fifth of seven. I think she would also have been stunned by the news that her parents did not get married until 1943, by which time she was twenty-four. This was done in secret as presumably everyone assumed they’d been married all along, and I surmise that with bombs falling all around them, it seemed wise to put their relationship on a secure footing.

When I felt I’d found out as much as I could, I wrote an account of the key events in Esmerelda’s life and distributed it around the family. More recently, when the 1921 Census was released online I checked it and saw that she’d stayed true to form. There in her entry—one simple line—were four false items of information; her first name, surname, age and marital status. Oh Esmeralda! I thought with a mixture of fondness honed by growing familiarity, and indulgent exasperation at her elastic attitude to the truth.

Because I never met Esmerelda, it’s been easy while rummaging casually through her secrets, to think of her as nothing more than a fictional character. And I can’t help feeling uncomfortable about that and wondering if in exposing the basic facts, I’ve betrayed her because what I can’t do is to put flesh on the story and understand her life. I can come up with plenty of theories about why she left her children: she was ashamed at being named the guilty party in her divorce…she was scared of her first husband…she was emotionally frozen after the death of baby Phyllis…she was lonely while her husband was away in the war…she fell helplessly, crazily in love with Ernest…

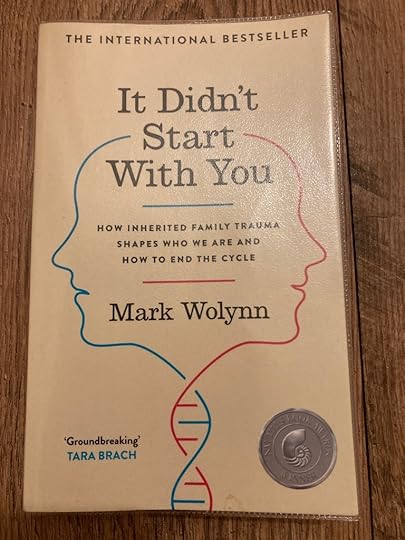

Any or all of these may be true and I’ve no way of knowing. But what I do know is that my own mother was full of fear and insecurity and often lacked empathy, and that this in turn impacted on me. Michelle Obama talked recently about her fearful mind. She says she’s always had it and calls it a life partner she didn’t choose. I’ve always had a fearful mind too and know I didn’t choose it. I’m sure that none of us do. In his book It Didn’t Start With You, Mark Wolynn argues that we all carry unresolved traumas from previous generations. We may not know where they come from but they live with us like ghosts and show up in our deepest fears. As St Augustine said, the dead are invisible; they are not absent. I’d never given this much thought before—after all, my family has not been directly affected by atrocities like the Holocaust or racial segregation which have quite rightly gained attention in relation to intergenerational trauma. My family’s upheavals have been more domestic in nature but these can still leave long-lasting scars. I suspect that Esmerelda was stressed, conflicted and secretive as a mother and that this contributed to my own mother’s problems. But then again Esmerelda herself didn’t get off to a good start as she was the youngest of ten and her father died six weeks before she was born. What kind of mothering did she get from an impoverished widow in poor health? There is currently a lot of research in epigenetics which is investigating how trauma might become biochemically encoded. Thinking like this reminds me that as humans we are all links in our own family chain and we involuntarily inherit all kinds of encumbrances. It makes me more empathic towards my parents, and at last I feel able to forgive some of the mistakes they undoubtedly made.

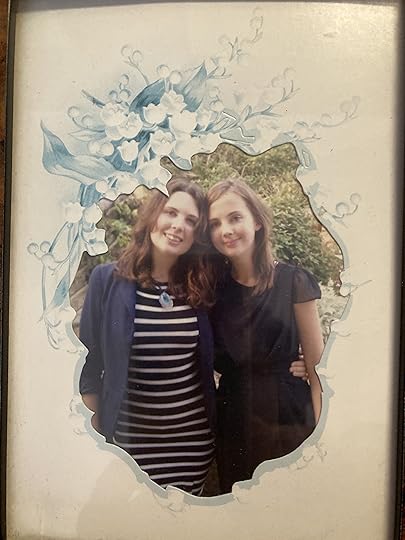

These days I spend a lot of time in my writing room and value having emotionally sustaining things around me. I’ve placed three photographs on the window ledge. The first one shows my mother—a dreamy bridesmaid at her sister’s wedding with Esmerelda standing behind in an awful hat and looking inscrutable as usual. The second is a photo of me on my fortieth birthday, and the third is of my two daughters, arm-in-arm. Four generations of women. I love to see these photos; our birthdates span a hundred and nine years and none of us knows all of the others but despite that and with all the uncertainties, the one thing I know for certain is that we are inextricably connected and always will be.