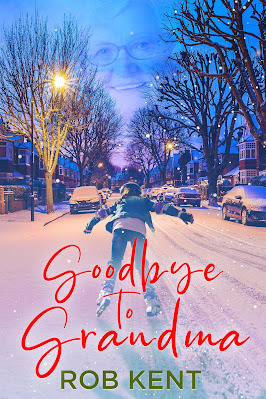

An Afterword for GOODBYE TO GRANDMA

When you hold my novelin your hands, Esteemed Reader, you hold my beating heart. That’s true nomatter which of my books you happen to be holding, even the adventure stories.There are chapters in all three Banneker Bones books I cannot read without tearsthreatening.

When you hold my novelin your hands, Esteemed Reader, you hold my beating heart. That’s true nomatter which of my books you happen to be holding, even the adventure stories.There are chapters in all three Banneker Bones books I cannot read without tearsthreatening.When you’re holdingGoodbye to Grandma, you’re holding a much younger version of my heart. Yet, 20years after its first draft, I still feel everything Hailey feels, and I stillcry at multiple places in the story every time I read them. What may read forsome as simple and unsophisticated in places is actually the faithful recordingof my experiences at a time in my life when I myself was a bit simpler and lesssophisticated.

Goodbye to Grandma isthe most directly autobiographical of my books. All my stories containautobiographical bits, whether I want them to or not. Whatever emotion I have aneed to express at the time usually works its way in to my fiction, even if Idon’t recognize it. That’s a big part of what makes fiction writing so satisfyingand cathartic. Also, risky.

I’ve never blastedgiant robot bees out of the sky whilst piloting a jetpack (alas) or even owneda pair of rollerblades (I’d fall and break things for sure). But my grandmotherdied when I was in the sixth grade and I could not cry at her funeral. Iactually lived a version of the funeral scenes right down to touching mygrandma’s lips and being attacked by a bee at her burial and yes, laughinghysterically in a way that the whole funeral parlor heard. I also played NickBottom in a production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Mr. Laurence in aproduction of Little Women.

I suspect part of mymotivation in choosing a female protagonist for this story was to throw off thereader’s suspicions that the character is me. Also, I really do remember beingso flippant as to think “my last book, Jim’s Monster, stared a boy so this oneshould star a girl.” 20 years later, I’m okay with Esteemed Reader knowing Ihad so much trouble processing my grandmother’s death, but I’m rather attached toHailey. I have an older sister and there’s quite a bit of me in Barry as well.

The Smith familyChristmas is a good-ish approximation of a Kent family Christmas circa 1992 andGrandma Smith isn’t a character. When I see her in my mind, I still see FrancisKent, who came to our house every Christmas morning and most Saturday morningswith doughnuts. She really did let me watch rated-R movies and even took me tothe theater to watch A Few Good Men at age 11 and I still clearly remember herface about an hour in as the gratuitous profanity dropped, yet the movie was sogood we didn’t leave.

My grandmother’s loveis one of my fondest childhood memories and I’ve carried it with me these manyyears. If there is an afterlife, at present, she’s the one I’m most lookingforward to seeing. And her dying as I was in middle school and going throughpuberty is the clearest marker in my mind of the end of my childhood. I neveragain experienced Christmas as the same holiday it was when she was alive andI’ve missed her every Christmas since.

It’s good that I firstwrote this novel 20 years ago when my memories of all my feelings from herfuneral and from being in the sixth grade were still fresh in my head. That’snot the version published as I’ve rewritten this story many, many, MANY times overthe years. But those core experiences have survived the many drafts, preservingwhat I wanted to express about grief then and what I still feel is worth expressingnow. This is also the book that gained me representation by a literary agentand was very nearly my debut novel with a couple publishers, so I haven’t setout to do much rewriting now as not to fix what isn’t broken.

The reason I’verevisited this story now, like checking in on an old friend, and the reason I decidedto publish it 20 years later is that the secondary plot of Hailey’s evolvingrelationship with Grandma Richmond strikes me as more relevant now than it didwhen I first wrote it. I had another grandmother type in my life, though shewasn’t a biological relative, but Grandma Richmond is actually an amalgamationof some other relatives of mine who were openly racist. I’m a heterosexual whitemale from a mostly all-white Indiana town who grew up in the 1980s and 90s, butwho thankfully had a library card and kept growing up after I left that town.

I have family memberswhom—as of the writing of this afterword—I have not spoken to since thepresidency of Donald Trump. I was tempted to give Grandma Richmond a MAGA hat,but I didn’t because I don’t want to overshadow my beloved story with theexistence of that heinous villain some of y’all felt fit to vote for aspresident. I mention him here only because two years after his presidency, Istill can’t forgive his supporters.

I’ve heard all thereasons why people supported that terrible man and I understand some of them onan intellectual level, like, “if I were an uniformed person who thoughttelevision shows were real, I guess I would believe the guy from The Apprenticewas good at business in spite of all the evidence he's just a born-rich criminal.” But no matter how hard I try to bend my mind, I justcan’t see how it was possible to have supported that man without having alsobeen a racist or at the very least, comfortable enough with racism to still be an enemy to my family. And I can’t accept the excuse, “I’m not a racist. I don’tpersonally hate anybody. I just want to support others who hate on mybehalf.”

Goodbye to Grandmatakes no explicit stance on religion or politics. I’m not comfortable writing explicitly about religion for children. They’re still figuring out their own views as to the nature of God and as someone who was successfully brainwashed (for a time) in my youth, I’m careful not to do the same to my young readers.

On the other hand, full disclosure: I'm only alive to publish this book as a month ago I should've definitely, absolutely died and didn't due to a set of circumstances I can only attribute to divine intervention. The number of coincidences I'd have to explain away becomes too improbable for serious consideration. And it's my third miraculous experience, though I imagine there've been far more that were simply less obvious. Suffice it to say, I'm done flirting with atheism.

I hope it’s possible to read this bookas a believer or an atheist without either view being challenged. Hailey’sstory is about loss and grief and that’s universal, whatever you believe happensor doesn’t happen after death. When Hailey’s father tells her that her deadneighbor’s soul is on its way to Heaven, it’s because that’s what my fathertold me, it’s what a lot of Indiana parents tell their children, and it’s anice thought. Not to acknowledge the reality of religious culture in thestory’s setting would be too great an omission, I think. But when mygrandmother died, all the thoughts of her in Heaven didn’t stop me from wantingher here and they didn’t help me to process the loss any differently. Gone isgone.

Hailey doesn’t careabout politics and neither does this story. The issue is racism. I’m not infavor of it, of course (see the Banneker Bones trilogy), nor do I feel it should be condoned. But I was raisedto hate the sin and love the sinner and I still feel that’s mostly a good idea.

I don’t think GrandmaRichmond is necessarily rehabilitated in this story in a lasting way and Idon’t think the Roosevelt family will be present for her next party. But I cansee Grandma Richmond is trying, and that’s not nothing. I don’t know, since thestory ends before we get there, that Hailey and Grandma Richmond are going tohave a lasting relationship (that’s a question for Esteemed Reader to resolve).I know only that Hailey is doing her best to be open to such a relationship becausethat’s what her Grandma Smith taught her and one of the ways in which GrandmaSmith lives on.

And that, whateverelse may come to pass, is beautiful and worthy of celebration.