Voynich Reconsidered: Arabic as precursor

In my ongoing search for meaning in the text of the Voynich manuscript, I have considered Arabic as a possible precursor language.

In order to assess Arabic as a precursor, we could start by examining whether there are any statistical similarities between the Voynich manuscript and Arabic documents of its era (which we may reasonably assume to be the fifteenth century). One useful metric is the frequency distribution of Arabic letters as written at that time.

An example is the letter frequency distribution in البداية والنهاية (The Beginning and the End), by Abulfida' ibn Kathir (1300-1373).

A modern edition of Al bidayah wal nihayah by ibn Kathir, in twenty-one volumes. Image credit: amazon.

For the Voynich manuscript, Glen Claston’s v101 transliteration is a starting point, The frequencies of the glyphs in the v101 transliteration, in descending order, and the frequencies of the letters in the works of ibn Kathir, have a correlation of 94.4 percent. That in itself is not remarkable: with two short sequences in descending order, it's easy to obtain a correlation of over 90 percent. Many European languages, as well as Hebrew, Persian and Ottoman Turkish, yield a similar correlation with the v101 transliteration.

However, it seems to me that the juxtaposition of these frequency tables opens the possibility of a provisional mapping of any chunk of Voynich text to Arabic. Having done so, it would probably be necessary to reverse the order of the letters in each transliterated word (for which there exist online tools such as https://onlinetexttools.com/reverse-text).

If the resulting text contained any recognisable Arabic words, we might be on the right track. If not, it might be necessary to try different approaches.

Here it should be remembered that Arabic uses an abjad script, in which the long vowels are written but the short vowels usually are not.

Alternative transliterations

One necessary consideration is whether the v101 transliteration is the right one to use.

v101 has a basic character set of seventy-one glyphs, which is far more than the number of letters in any alphabet of a phonetic natural language. There are several groups of visually similar glyphs such as {6}, {7}, {8} and {&}; it makes sense to combine each such group into a single glyph. We can disaggregate glyphs that look like strings, e.g. {m} => {iN}, {n} => {iN}. In both cases, that will reduce the size of the character set and make v101 more like a representation of a natural language.

Conversely, we can make distinctions between initial, interior, final and isolated glyphs. That will increase the size of the character set.

In all cases, these variants change the frequency table and consequently change the mapping from glyphs to any natural language.

In exploring Arabic and other natural languages as possible precursors to the Voynich manuscript, I felt it advisable to examine alternatives to v101. Accordingly, I developed a range of alternative transliterations of the Voynich text, all based on v101 but differing from v101 in one or more respects. I numbered these transliterations v101④ through v202. The ④ signifies that in all the transliterations, I treated the v101 glyph pair {4o} as a single glyph, to which I assigned the Unicode symbol ④.

For comparison of the Voynich text with the Arabic language, I used letter frequencies derived from the works of Ibn Kathir.

To prioritize my Voynich transliterations, I started by calculating the statistical correlations between the glyph frequencies and the Arabic letter frequencies, using the R-squared function (RSQ in Microsoft Excel). However, as expected with two short descending sequences, most of the correlations were well in excess of 90 percent. Substantial differences between transliterations, for example combining the {2} group of glyphs, resulted in quite small changes in the frequency correlations.

Frequency differences

I therefore adopted an alternative metric, namely the average frequency difference. Mathematically, this is the average of the absolute differences between the frequency of a precursor letter and the frequency of the equally ranked Voynich glyph. My idea was that the lowest average frequency difference should represent the best fit between a transliteration and the presumed precursor language.

On this metric, I found that the transliteration which I had numbered v171 was the best fit for ibn Kathir's Arabic alphabet. Apart from the treatment of {4o}, the v171 transliteration has the following differences from v101:

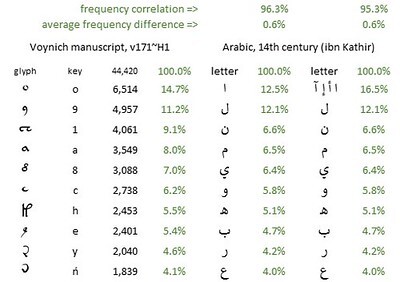

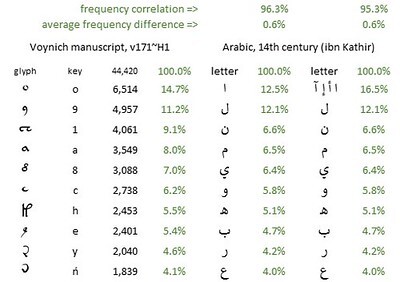

Below is a juxtaposition of the frequencies of the top ten glyphs in the v171 transliteration, and of those of the top ten Arabic letters. The average frequency difference between v171 and Ibn Kathir's Arabic (calculated on all 43 letters) is 0.64 percent.

The frequencies of the ten most common glyphs in the Voynich manuscript; and those of the ten most common letters in fourteenth-century Arabic. The glyph frequencies are from author's v171 transliteration, "herbal" section. The Arabic letter frequencies are based on the works of Ibn Kathir, with the variants of alef (ﺍ ﺃ ﺇ ﺁ) shown separately or combined. Author's analysis.

The next step is to explore the potential of these juxtapositions as correspondences or mappings. For example, the Voynich {o} could map to and from the Arabic ا (alef). Thereby, we could map some of the most common Voynich "words", such as {8am}, {oe} and {1oe}, to text strings in Arabic. We could then search appropriate corpora of the Arabic language to determine whether these strings are real words.

Test mappings

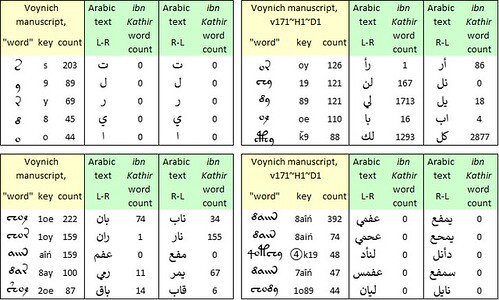

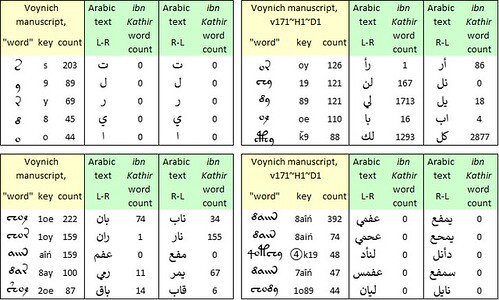

Below is a summary of my test mappings of the top five Voynich "words" of one, two, three and four glyphs.

Test mappings of the top five "words" of one, two, three and four glyphs in the Voynich manuscript, v171 transliteration, "herbal" section, to text strings in medieval Arabic. Author's analysis.

We see here what I am inclined to call the abjad effect, which I had already observed with Hebrew, Persian and Ottoman Turkish. Most of the Voynich "words" of two or three glyphs map to real Arabic words. They do so whether the glyphs are read from left to right, or from right to left. But in an abjad script, almost any random string of two or three letters will be a real word. At the levels of one glyph and four glyphs, the mapping breaks down.

An alphabetic cipher?

These test mappings do not entirely exclude Arabic as a precursor language of the Voynich manuscript.

As Massimiliano Zattera demonstrated at the Voynich 2022 conference, in almost every Voynich "word" the glyphs follow a sequence, a kind of alphabetic order. Indeed, Zattera called the sequence a "slot alphabet". We are compelled to imagine that if the Voynich scribes mapped their manuscript from precursor documents, they re-ordered the glyphs in every "word". That would imply that we could take any one of our Arabic text strings, scramble the letters, and reverse-engineer it to the same Voynich "word" from which we started.

For example, in the above tests I mapped the Voynich "word" {1o89} to the Arabic strings ليان and نايل which are not real words. However, both strings have an anagram الين which is rare, occurring just six times in ibn Kathir. According to our mapping, if the Voynich scribes had read it from right to left, they would have mapped it to {o981}. If read from left to right, it would map to {189o}. The slot alphabet does not permit either of these sequences, so the scribes would have re-ordered them to {1o89}.

To take this idea further would require a good knowledge of Arabic (preferably medieval Arabic), a head for anagrams or Scrabble, and plenty of computing power (or patience).

In order to assess Arabic as a precursor, we could start by examining whether there are any statistical similarities between the Voynich manuscript and Arabic documents of its era (which we may reasonably assume to be the fifteenth century). One useful metric is the frequency distribution of Arabic letters as written at that time.

An example is the letter frequency distribution in البداية والنهاية (The Beginning and the End), by Abulfida' ibn Kathir (1300-1373).

A modern edition of Al bidayah wal nihayah by ibn Kathir, in twenty-one volumes. Image credit: amazon.

For the Voynich manuscript, Glen Claston’s v101 transliteration is a starting point, The frequencies of the glyphs in the v101 transliteration, in descending order, and the frequencies of the letters in the works of ibn Kathir, have a correlation of 94.4 percent. That in itself is not remarkable: with two short sequences in descending order, it's easy to obtain a correlation of over 90 percent. Many European languages, as well as Hebrew, Persian and Ottoman Turkish, yield a similar correlation with the v101 transliteration.

However, it seems to me that the juxtaposition of these frequency tables opens the possibility of a provisional mapping of any chunk of Voynich text to Arabic. Having done so, it would probably be necessary to reverse the order of the letters in each transliterated word (for which there exist online tools such as https://onlinetexttools.com/reverse-text).

If the resulting text contained any recognisable Arabic words, we might be on the right track. If not, it might be necessary to try different approaches.

Here it should be remembered that Arabic uses an abjad script, in which the long vowels are written but the short vowels usually are not.

Alternative transliterations

One necessary consideration is whether the v101 transliteration is the right one to use.

v101 has a basic character set of seventy-one glyphs, which is far more than the number of letters in any alphabet of a phonetic natural language. There are several groups of visually similar glyphs such as {6}, {7}, {8} and {&}; it makes sense to combine each such group into a single glyph. We can disaggregate glyphs that look like strings, e.g. {m} => {iN}, {n} => {iN}. In both cases, that will reduce the size of the character set and make v101 more like a representation of a natural language.

Conversely, we can make distinctions between initial, interior, final and isolated glyphs. That will increase the size of the character set.

In all cases, these variants change the frequency table and consequently change the mapping from glyphs to any natural language.

In exploring Arabic and other natural languages as possible precursors to the Voynich manuscript, I felt it advisable to examine alternatives to v101. Accordingly, I developed a range of alternative transliterations of the Voynich text, all based on v101 but differing from v101 in one or more respects. I numbered these transliterations v101④ through v202. The ④ signifies that in all the transliterations, I treated the v101 glyph pair {4o} as a single glyph, to which I assigned the Unicode symbol ④.

For comparison of the Voynich text with the Arabic language, I used letter frequencies derived from the works of Ibn Kathir.

To prioritize my Voynich transliterations, I started by calculating the statistical correlations between the glyph frequencies and the Arabic letter frequencies, using the R-squared function (RSQ in Microsoft Excel). However, as expected with two short descending sequences, most of the correlations were well in excess of 90 percent. Substantial differences between transliterations, for example combining the {2} group of glyphs, resulted in quite small changes in the frequency correlations.

Frequency differences

I therefore adopted an alternative metric, namely the average frequency difference. Mathematically, this is the average of the absolute differences between the frequency of a precursor letter and the frequency of the equally ranked Voynich glyph. My idea was that the lowest average frequency difference should represent the best fit between a transliteration and the presumed precursor language.

On this metric, I found that the transliteration which I had numbered v171 was the best fit for ibn Kathir's Arabic alphabet. Apart from the treatment of {4o}, the v171 transliteration has the following differences from v101:

• m=INTo have some assurance of mapping from a single Voynich “language”, I used the text of the “herbal” section only.

• M=iIN

• n=iN.

Below is a juxtaposition of the frequencies of the top ten glyphs in the v171 transliteration, and of those of the top ten Arabic letters. The average frequency difference between v171 and Ibn Kathir's Arabic (calculated on all 43 letters) is 0.64 percent.

The frequencies of the ten most common glyphs in the Voynich manuscript; and those of the ten most common letters in fourteenth-century Arabic. The glyph frequencies are from author's v171 transliteration, "herbal" section. The Arabic letter frequencies are based on the works of Ibn Kathir, with the variants of alef (ﺍ ﺃ ﺇ ﺁ) shown separately or combined. Author's analysis.

The next step is to explore the potential of these juxtapositions as correspondences or mappings. For example, the Voynich {o} could map to and from the Arabic ا (alef). Thereby, we could map some of the most common Voynich "words", such as {8am}, {oe} and {1oe}, to text strings in Arabic. We could then search appropriate corpora of the Arabic language to determine whether these strings are real words.

Test mappings

Below is a summary of my test mappings of the top five Voynich "words" of one, two, three and four glyphs.

Test mappings of the top five "words" of one, two, three and four glyphs in the Voynich manuscript, v171 transliteration, "herbal" section, to text strings in medieval Arabic. Author's analysis.

We see here what I am inclined to call the abjad effect, which I had already observed with Hebrew, Persian and Ottoman Turkish. Most of the Voynich "words" of two or three glyphs map to real Arabic words. They do so whether the glyphs are read from left to right, or from right to left. But in an abjad script, almost any random string of two or three letters will be a real word. At the levels of one glyph and four glyphs, the mapping breaks down.

An alphabetic cipher?

These test mappings do not entirely exclude Arabic as a precursor language of the Voynich manuscript.

As Massimiliano Zattera demonstrated at the Voynich 2022 conference, in almost every Voynich "word" the glyphs follow a sequence, a kind of alphabetic order. Indeed, Zattera called the sequence a "slot alphabet". We are compelled to imagine that if the Voynich scribes mapped their manuscript from precursor documents, they re-ordered the glyphs in every "word". That would imply that we could take any one of our Arabic text strings, scramble the letters, and reverse-engineer it to the same Voynich "word" from which we started.

For example, in the above tests I mapped the Voynich "word" {1o89} to the Arabic strings ليان and نايل which are not real words. However, both strings have an anagram الين which is rare, occurring just six times in ibn Kathir. According to our mapping, if the Voynich scribes had read it from right to left, they would have mapped it to {o981}. If read from left to right, it would map to {189o}. The slot alphabet does not permit either of these sequences, so the scribes would have re-ordered them to {1o89}.

To take this idea further would require a good knowledge of Arabic (preferably medieval Arabic), a head for anagrams or Scrabble, and plenty of computing power (or patience).

Published on March 18, 2024 11:09

•

Tags:

arabic, ibn-kathir, voynich

No comments have been added yet.

Great 20th century mysteries

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pe

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pen And Sword Books, April 2024), Voynich Reconsidered (Schiffer Books, August 2024), and D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 Revisited (Schiffer Books, coming in 2026),

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

- Robert H. Edwards's profile

- 68 followers