Voynich Reconsidered: La Divina Commedia

Any mapping of the Voynich text to natural languages is necessarily based on the assumption that the Voynich scribes created the manuscript by some kind of process based on precursor documents in such languages. To my mind, the text gives little clue as to what those languages might have been. (The illustrations possibly yield clues, but I have no expertise in that area.)

However, the distance-decay hypothesis (to which I have alluded in other posts) gives us some reason to think that a manuscript found in Frascati, Italy, might have some link with the languages spoken or written in Italy.

In my early research for my book Voynich Reconsidered (Schiffer Publishing, 2024), I experimented with mapping from the Voynich text to medieval Italian. The mapping was based on the frequencies of the Voynich glyphs (in various transliterations of my own devising) and the frequencies of the letters in medieval Italian (as represented by the OVI corpus). This mapping yielded a sequence of Italian text strings. Nearly all of the strings could be found as real words in the corpus.

The OVI corpus is intended primarily for speakers of Italian (of whom, I am not one), and does not include translations of Italian words into any other language. I was not able to determine the meanings of all of the words that I found; nor to judge whether the words, in the mapped sequence, made any sense.

The home page of the OVI corpus of medieval Italian at http://gattoweb.ovi.cnr.it. Image credit: Istituto Opera del Vocabulario Italiano.

In any case, I wondered whether the OVI corpus was an accurate reflection of the presumed source documents that the Voynich scribes had on their walls or tables. My reasons for doubt included the following:

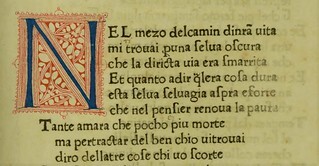

The first nine lines of La Divina Commedia, Foligno edition of 1472. Image credit: Biblioteca Europea di Informazione e Cultura; public domain.

The full text of La Divina Commedia is available online, from Project Gutenberg and elsewhere; but as far as I can tell, all the online versions are written in (what appears to be) a modernised Italian which diverges from that of the 1472 edition. To take just one example, namely the first line:

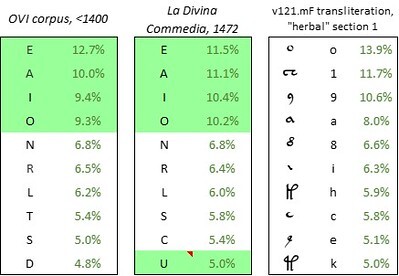

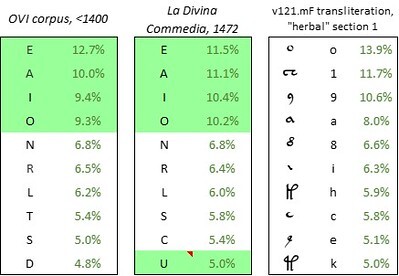

Of the twenty-one letters in the alphabet of the reconstructed Commedia, nine had the same rankings as those in the OVI corpus. For example, the seven most frequent letters in OVI and in the Commedia were E, A, I, O, N, R, and L, in that order. Only from the eighth letter onwards were there some slight divergences in the rankings. In particular the letter U, which in the 1472 edition was also used in place of V, moved into the top ten.

Having generated a frequency table for Italian letters, I then tested a range of alternative transliterations of the Voynich manuscript, which I numbered from v101④ to v202. As I have mentioned in other posts, the ④ reflects my view that the v101 glyph pair {4o} is a single glyph; in all my transliterations, I assigned this glyph the Unicode symbol ④.

In prioritising my transliterations vis-à-vis any presumed precursor language, I used two metrics, as follows:

On this metric, the transliteration which best fitted the Italian language of 1472 (as represented by my reconstruction of the Foligno edition of La Divina Commedia) was the one that I numbered v121.mF. This transliteration yielded both the highest frequency correlation (98.3 percent) and the lowest average frequency difference (0.30 percent).

What I call v121 is in fact a family of transliterations, with some variations. The differences between v121 and v101 are as follows:

The top ten letters in the OVI corpus and in La Divina Commedia (reconstructed 1472 edition), and the top ten glyphs in the Voynich manuscript, v121.mF transliteration, “herbal” section. Author’s analysis.

The next heroic step was to explore these juxtapositions as correspondences or mappings: in other words, to conjecture that the Voynich scribes mapped the Italian E to the glyph {o}, the Italian A to the glyph {1}, and so on.

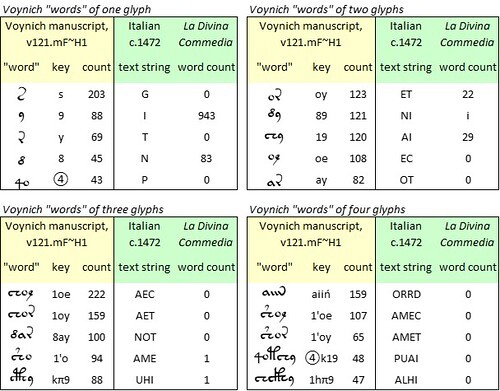

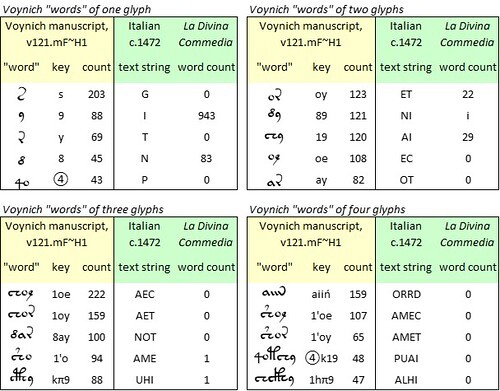

It was simple enough to test this conjecture. We could take, say, the five most common Voynich “words” and see whether they map to real words in Italian. In order to see to what extent such a mapping might hold water, I selected the most common Voynich “words” of one, two, three and four glyphs. The results were as follows.

The five most common "words" of one, two, three and four glyphs in the Voynich manuscript, v121.mF transliteration, "herbal" section; and test mappings of these "words" to Italian as written in 1472. Author's analysis.

Notwithstanding the good statistical fit between the v121.mF transliteration and La Divina Commedia, this test did not produce many real Italian words, apart from a few words of one or two letters.

We may draw a number of possible conclusions: that the precursor languages of the Voynich manuscript do not include Italian; or that they do, but not Italian as it appeared in printed books around 1472; or that the period is about right, but that La Divina Commedia is a not a good representation of the precursor documents. Alternatively: that the v121.mF transliteration is not the best one; or that, as Prescott Currier said in 1976, the Voynich “words” are not really words.

Finally, we could recall Massimiliano’s concept of the “slot” alphabet” and conjecture that the Voynich scribes re-ordered the glyphs in each Voynich “word”. In that case, we could conceive the possibility that at some point, a scribe came across the real Italian word TEMA, which he mapped to the glyph string {yo’1}. Since the “slot alphabet” did not permit this sequence, he re-ordered it to {1’oy}, or {2oy} as it is written in v101: which is a real Voynich “word”.

However, the distance-decay hypothesis (to which I have alluded in other posts) gives us some reason to think that a manuscript found in Frascati, Italy, might have some link with the languages spoken or written in Italy.

In my early research for my book Voynich Reconsidered (Schiffer Publishing, 2024), I experimented with mapping from the Voynich text to medieval Italian. The mapping was based on the frequencies of the Voynich glyphs (in various transliterations of my own devising) and the frequencies of the letters in medieval Italian (as represented by the OVI corpus). This mapping yielded a sequence of Italian text strings. Nearly all of the strings could be found as real words in the corpus.

The OVI corpus is intended primarily for speakers of Italian (of whom, I am not one), and does not include translations of Italian words into any other language. I was not able to determine the meanings of all of the words that I found; nor to judge whether the words, in the mapped sequence, made any sense.

The home page of the OVI corpus of medieval Italian at http://gattoweb.ovi.cnr.it. Image credit: Istituto Opera del Vocabulario Italiano.

In any case, I wondered whether the OVI corpus was an accurate reflection of the presumed source documents that the Voynich scribes had on their walls or tables. My reasons for doubt included the following:

• The OVI corpus consists of texts written before the year 1400.For these reasons, I thought it worthwhile to calculate the Italian letter frequencies on the basis of another corpus, from a slightly later period than the OVI. For this purpose, I again turned to Dante Alighieri’s La Divina Commedia, specifically the first printed edition, launched by Johann Neumeister in the city of Foligno in the year 1472.

• Of five samples from the parchment of the Voynich manuscript, the most recent (from folio 8) was carbon-dated to the period 1394 to 1458 with 92.2 percent probability.

• We might reasonably assume that the scribes wrote the manuscript after the latest date of production of the parchment.

• We might conjecture that the scribes worked from printed source documents (as opposed to manuscripts). Since Johannes Gutenberg introduced commercial printing in Europe around 1455, this assumption would date the Voynich text to about 1455 at the earliest.

• The Italian language (like any language) surely evolved over time, and must have undergone changes in the letter frequencies.

The first nine lines of La Divina Commedia, Foligno edition of 1472. Image credit: Biblioteca Europea di Informazione e Cultura; public domain.

The full text of La Divina Commedia is available online, from Project Gutenberg and elsewhere; but as far as I can tell, all the online versions are written in (what appears to be) a modernised Italian which diverges from that of the 1472 edition. To take just one example, namely the first line:

The 1472 edition reads: Nel mezo delcamin dinrã uitaI wanted to reconstruct the text that the Voynich scribes would have seen if, hypothetically, they had had the 1472 edition of the Commedia on their work table. Accordingly, working from the Gutenberg version, I restored the abbreviations and spelling conventions that I could detect in the 1472 edition. Having done so, I recalculated the letter frequencies.

The Gutenberg version reads: Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita.

Of the twenty-one letters in the alphabet of the reconstructed Commedia, nine had the same rankings as those in the OVI corpus. For example, the seven most frequent letters in OVI and in the Commedia were E, A, I, O, N, R, and L, in that order. Only from the eighth letter onwards were there some slight divergences in the rankings. In particular the letter U, which in the 1472 edition was also used in place of V, moved into the top ten.

Having generated a frequency table for Italian letters, I then tested a range of alternative transliterations of the Voynich manuscript, which I numbered from v101④ to v202. As I have mentioned in other posts, the ④ reflects my view that the v101 glyph pair {4o} is a single glyph; in all my transliterations, I assigned this glyph the Unicode symbol ④.

In prioritising my transliterations vis-à-vis any presumed precursor language, I used two metrics, as follows:

• The statistical correlation (R-squared} between the glyph frequencies in the transliteration and the letter frequencies in the precursor language;The frequency correlations do not differ much from one transliteration to another, and are typically well over 90 percent for any pairing of transliteration and precursor language. I am inclined therefore to use the average frequency difference as the more powerful metric.

• The average frequency difference, defined as the average of the absolute differences between glyph frequencies and equally-ranked letter frequencies in the precursor language.

On this metric, the transliteration which best fitted the Italian language of 1472 (as represented by my reconstruction of the Foligno edition of La Divina Commedia) was the one that I numbered v121.mF. This transliteration yielded both the highest frequency correlation (98.3 percent) and the lowest average frequency difference (0.30 percent).

What I call v121 is in fact a family of transliterations, with some variations. The differences between v121 and v101 are as follows:

• As mentioned above, I replaced the v101 {4o} with the single glyph ④.The differences between v121.mF and v121 are as follows:

• I redefined the v101 glyph {2} and all its variants {3}, {5}, {!}, {%}, {+} and {#} as 1', in other words as the glyph {1} plus a catch-all accent {‘}.

• I disaggregated the v101 glyph {m} into the string iiN; but allowed the v101 {M} and {n} to remain as distinct glyphs from {N}.As an illustration, a juxtaposition of the frequencies of the top ten letters in the 1472 La Divina Commedia, and those of the top ten glyphs in v121.mF, looks like this:

• I disaggregated each of the “bench gallows” glyphs into its vertical component and its “bench”. The “bench” resembles an elongated {1}, but I did not wish to assume that it was the same as {1}; so I assigned it a new key, π (the Greek letter pi). Under this process, {F} became fπ, {G} became gπ, and so on.

The top ten letters in the OVI corpus and in La Divina Commedia (reconstructed 1472 edition), and the top ten glyphs in the Voynich manuscript, v121.mF transliteration, “herbal” section. Author’s analysis.

The next heroic step was to explore these juxtapositions as correspondences or mappings: in other words, to conjecture that the Voynich scribes mapped the Italian E to the glyph {o}, the Italian A to the glyph {1}, and so on.

It was simple enough to test this conjecture. We could take, say, the five most common Voynich “words” and see whether they map to real words in Italian. In order to see to what extent such a mapping might hold water, I selected the most common Voynich “words” of one, two, three and four glyphs. The results were as follows.

The five most common "words" of one, two, three and four glyphs in the Voynich manuscript, v121.mF transliteration, "herbal" section; and test mappings of these "words" to Italian as written in 1472. Author's analysis.

Notwithstanding the good statistical fit between the v121.mF transliteration and La Divina Commedia, this test did not produce many real Italian words, apart from a few words of one or two letters.

We may draw a number of possible conclusions: that the precursor languages of the Voynich manuscript do not include Italian; or that they do, but not Italian as it appeared in printed books around 1472; or that the period is about right, but that La Divina Commedia is a not a good representation of the precursor documents. Alternatively: that the v121.mF transliteration is not the best one; or that, as Prescott Currier said in 1976, the Voynich “words” are not really words.

Finally, we could recall Massimiliano’s concept of the “slot” alphabet” and conjecture that the Voynich scribes re-ordered the glyphs in each Voynich “word”. In that case, we could conceive the possibility that at some point, a scribe came across the real Italian word TEMA, which he mapped to the glyph string {yo’1}. Since the “slot alphabet” did not permit this sequence, he re-ordered it to {1’oy}, or {2oy} as it is written in v101: which is a real Voynich “word”.

No comments have been added yet.

Great 20th century mysteries

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pe

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pen And Sword Books, April 2024), Voynich Reconsidered (Schiffer Books, August 2024), and D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 Revisited (Schiffer Books, coming in 2026),

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

- Robert H. Edwards's profile

- 68 followers