Revisiting the Professionalization of Interior Design in Antwerp

In October, I was delighted to visit the University of Antwerp at the invitation of Professor Els De Vos, Chair of the Interior Architecture program, to give a guest lecture there. Although the occasion of the lecture was as part of a programme of events celebrating the tenth anniversary of the University’s Faculty of Design Science, the institution has a much longer history, as Els explains in a co-authored text (summarised on the University of Antwerp website):

The origins of the Faculty of Design Sciences can be traced back to the seventeenth century. In today's faculty, however, the only discipline that is directly associated with the Academy of Antwerp - historically speaking - is architecture. Architecture was taught at the Royal Academy of Antwerp (founded in 1663) from 1765 to 1946, or for about 180 years.

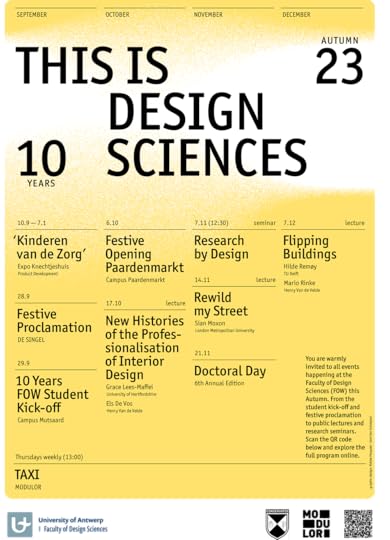

The city-centre campus is absolutely beautiful. The buildings of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts - where the Antwerp Six fashion designers trained - and the Faculty of Design Science, on and around Mutsaardstraat, are historically significant. On my arrival, I noticed an enormous poster at the gatehouse advertising the 10th anniversary series, including my lecture (see photo at top).

A video portrait of the University of Antwerp.

Professionalization as a Focus in Interior Design HistoryThe Faculty has a strong programme in interior architecture so in my lecture, titled ‘New Histories of the Professionalization of Interior Design’, I took the opportunity to revisit my 2008 Journal of Design History article, ‘Professionalization as a Focus in Interior Design History’. That article tracked a process of professionalization as context for a special themed issue of the JDH, ‘Professionalizing Interior Design 1870–1970’, which I co-edited with Prof Anne Wealleans (Massey). My starting point in preparing my Antwerp lecture was to ask: What has changed in the 15 years since my first article on the subject was published? This field has undergone several significant name changes during its history from decoration, to interior design, to interior architecture. In discussing the professionalization in interior design, or interior architecture, I was keen to explore new work in the field. I foregrounded work which responds to, and contributes to, the decolonization of design through the crafting of new national histories, such as Dr Catriona Quinn’s work on the Australian interior design profession. Dr Miranda Garrett insists that gender remains a relevant lens through which to focus histories of interior design. Garrett’s study of gender and professionalism in late nineteenth century Britain extends from her PhD, ‘Professional Women Interior Decorators in Britain, 1871 to 1899’ (2018), which I examined, to more recent chapters in edited collections. I next turned to the broader study of professionalization in design in the last century, and particularly fashion design and industrial design, for instance in the work of Dr Leah Armstrong, such as her co-edited book Fashioning Professionals. What can these latter studies of the processes of professionalization in neighbouring sub-fields of design bring to knowledge and understanding of the processes of professionalization in interior architecture specifically, I asked. I then introduced some of my own recently published research, building on wider currents in design history and subjectivity (such as a special issue of Design and Culture that I co-edited with Prof Kjetil Fallan in 2015) to examine new directions in interior design history informed by sensory history. I shared a new chapter, ‘Hands at Home? Textures, Tactility and Touch in Interior Design’ published this September in a collection of essays edited by John Potvin, Marie-Éve Marchand and Benoit Beaulieu (2023). Ultimately, my lecture asked how the processes of professionalization accommodate subjectivity, diversity, the senses and the emotions.

Poster advertising events celebrating 10 years of the Faculty of Design Sciences

Professionalization of Interior Architecture in Europe by Els De VosProf De Vos, whose research concerns, in her own words, ‘housing, interior architecture, residential culture, gender, diversity and public space in the second half of the 20th century’, also gave a lecture at the same event, presenting a project she undertook:

for ECIA, the European Council of Interior Architects, about the degree of professionalization of the discipline of interior architecture across several European countries. This research is a subproject of the European funded ECIA-BCSP project: Building on connections for a stronger profession.

Members of the ECIA attended Els’ lecture online and the slides and a recording are available. Referencing my definition of professionalization Prof De Vos examined a variety of elements of the professionalization process, from education, professional organisations and legislation, to nomenclature, recognition, interdisciplinarity, gender and diversity. Prof De Vos’s current research sees her leading a working group for the COST Action on European Middle Class Mass Housing. This recalls her PhD (2012) on the ‘the architectural, social and gender-differentiated mediation of housing in Flanders in the 1960s-1970s’.

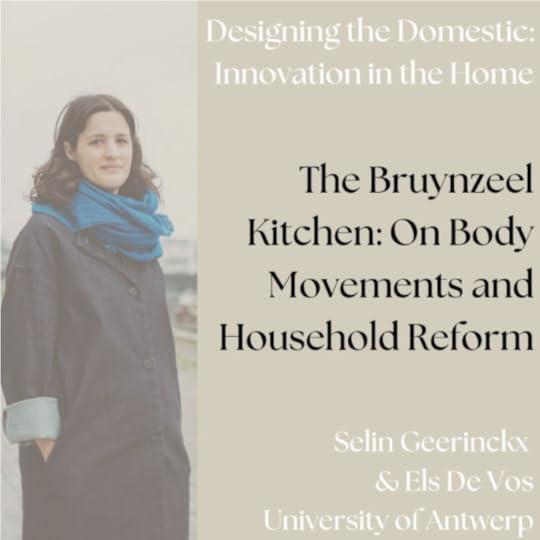

Doctoral Research in the History of Interior ArchitectureBefore the evening lectures, we met with four doctoral researchers working with Els, and with Professor Fredie Flore (KU Leuven), who presented their research in progress and I was able to respond, largely positively, in a way that I hope was useful. As well as a talk about the very beginning of a research project by Georgina Pantazopoulou, two of the students, Sam Vanhee and Benoît Vandevoort, shared their complementary research into the history of interior architecture education. One output of their group research is their article, ‘Beyond Distinction-Based Narratives. Interior Design's Educational History as a Knowledge Base’. Another PhD candidate, Selin Geerinckx, discussed her doctoral research on the bodily and mental effects of modern(ist) housing ideologies. As well as the work of ‘choreographer and dance pedagogue Lea Daan who brought daily live radio gym classes via national radio directly into Belgian homes during the 1930s as part of public health, education and home culture’, Selin’s research encompasses Dutch designer Piet Zwart and architect Koen Limperg’s Bruynzeel Kitchen, in terms of ‘Body Movements and Household Reform’. The latter was presented with Prof De Vos, at a recent Design History Society online symposium, Designing the Domestic: Innovation in the Home. Read more about Selin’s research in this DHS interview. The work of these doctoral students will provide the next chapter in a survey of new histories of the professionalization of interior architecture.

Selin Geerinckx was interviewed by the Design History Society in connection with its symposium.

Antwerp: Diamond DestinationOn this, my first visit to Belgium, I discovered that Antwerp is a truly remarkable place. Known as the centre of the diamond trade, it also has the second-largest port in Europe, after its near neighbour Rotterdam, due to its proximity to the North Sea. I enjoyed the views of the city and the river Scheldt from Het Steen, an C11th fortress on the river Scheldt and Antwerp’s oldest building. I was charmed and impressed by the Grote Markt featuring the city hall (1561-5), listed by UNESCO as one of the Belfries of Belgium and France, and the Cathedral (1352-1521). But what really blew me away was Museum Plantin-Moretus on the leafy Vrijdagmarkt square.

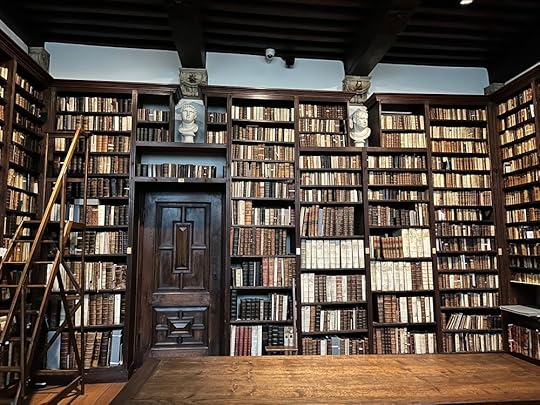

Christophe Plantin moved from France to Antwerp c. 1550 and started his own printing press in 1555. His five surviving daughters were educated in reading, languages, needle crafts and lacemaking so that they could proof-read for the press, and they ran a lace business. Plantin also provided a bookbinding service and rented homes to tenants on his premises. By 1570, Plantin’s publishing house was the largest in the world with 22 presses, branches in Paris and Leiden, and 80 staff, including his son-in-law, Jan Moretus, to whom he left the business in his will. The Officina Plantiniana worked with cartographers and scientists to publish maps, atlases, the first Dutch dictionary, and progressive and classic scientific works. Plantin introduced the Garamond typeface, and held a collection of c. 80 type faces. He also innovated with a multi-lingual bible in which Latin, Greek, Hewbrew, Chaldean and Ancient Syrian sit side by side on the pages. Plantin’s enormous library served as the chapel for the family and employees. The Plantin-Moretus family were painted by family friend Peter Paul Rubens who also designed 24 title pages and illustrated some books for the press. The printing workshop is home to the two oldest surviving printing presses in the world. Nine generations of the Plantin-Moretus family ran the publishing press continuously before, no longer needing to work, in 1876 they sold the premises to the city of Antwerp, to be preserved as a museum. In 2005, Museum Plantin-Moretus became the first museum to be accorded UNESCO World Heritage status, and it remains the only museum on the list. The Plantin-Moretus business archive, spanning the years 1555-1876 was inscribed by UNESCO in 2002. Visit this amazing time-capsule if you can!

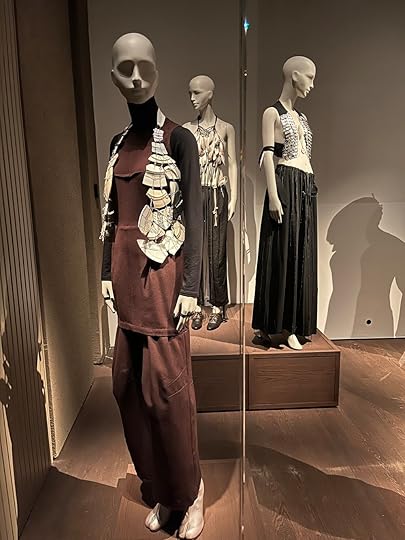

Before I left Antwerp, I visited the permanent collection gallery at MoMu, fronted with an impressive foyer and stairwell designed by architect Marie-José Van Hee. MoMu holds 38,000 items documenting the history of fashion, especially in Belgium, and with a focus on the Antwerp Six. I was sorry to miss the current temporary exhibition, Echo: Wrapped in Memory for reasons of time.

Given my current research topic, a design history of and through hands, I couldn’t resist buying an Antwerp treat commemorating the legend of Brabo. Roman hero Brabo defeated and chopped off the hand of the giant Druon Antigoon as punishment for the giant’s practice of chopping off the right hands of boat men who refused to pay his toll for crossing the river Scheldt. All the hands were thrown in the river Scheldt. The Dutch for hand throwing is handwerpen which sounds a bit like Antwerpen. Bon appétit!