WHAT’S THE MOST CHRISTMASSY MEDICAL OBJECT?

A lot of readers enjoy seasonal reading this time of year. I know this from the popularity of books such as Sue Moorcroft’s A Skye Full of Stars and Elaine Everest’s A Christmas Wish at Woolworth’s. So perhaps it should not have surprised me to be asked, “What’s the most Christmassy object in your book?”

Makes an excellent Christmas gift

Makes an excellent Christmas giftI scratched my head. My latest book, The History of Medicine in Twelve Objects focuses, as the title suggests, on a dozen iconic objects in medical history. While writing it, I gave hardly a thought to the birth of Jesus. But, with Christmas now less than a week away, I offer this festive tale of the X-ray machine.

Roentgen (1845-1923) with a beard fit for Santa

Roentgen (1845-1923) with a beard fit for SantaIt was December 1895. For over six weeks, German physicist Wilhelm Conrad Roentgen had been busy in his lab in Würzburg – so busy that he missed meals, slept on a cot by his lab bench, and, it’s safe to say, hadn’t even begun Christmas shopping. What exactly was that radiation coming out of his cathode ray tube? Unlike a beam of light, these rays could go through black cardboard. Roentgen tried blocking the rays with a book, some wood, rubber, a deck of cards, and various metal sheets. Only lead stopped them completely.

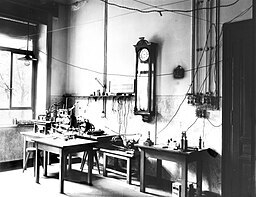

Roentgen’s lab in Würzburg

Roentgen’s lab in WürzburgKeen to find out what her husband had been doing, Anna Bertha Roentgen visited the lab. She was asked to hold out a photographic plate in front of the beam. This produced an image of her hand, complete with the bones of her fingers and the ring she was wearing. Definitely one for the family album.

Anna Roentgen’s hand X-ray, 1895

Anna Roentgen’s hand X-ray, 1895Roentgen didn’t know what the rays were, so he called them ‘X’. His publication of his discovery on December 28 made the headlines. Public speculation went wild. Could peeping toms use the rays for peering through women’s knickers? In response to this fear, one London manufacturer began making lead-lined underwear.

As it turned out, there were more serious worries. The first medical X-ray was just weeks later. In January 1896, Birmingham doctor John Hall-Edwards (1858–1926) took an image of a needle stuck in the hand of his assistant. Hall-Edwards had an interest in photography and went on to take many more radiographs during his career.

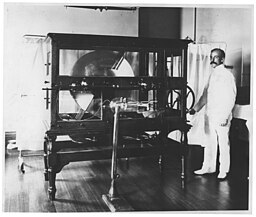

An early X-ray machine

An early X-ray machineX-rays weren’t just used for making a diagnosis. Doctors also used them as remedies for a miscellany of conditions, like moles and skin conditions ranging from acne to TB of the skin.

Unfortunately, it soon emerged that prolonged X-ray exposure causes dermatitis, burns, ulceration, hair loss – and worse. Hall-Edwards had to have his left arm amputated below the elbow when he developed cancer. He then lost four fingers from his right hand, leaving him with just one thumb. His left hand can be found in the Chamberlain Museum of Pathology at the University of Birmingham.

Since then, medics have become far more cautious in their use of X-rays and there are plenty of safeguards. What’s more, the concept making the body transparent has led to imaging methods that don’t use X-rays. So that’s a happy ending, although not an ending as such, because as you know inventors love inventing.

Wishing you all a Merry Christmas and a happy, healthy New Year.