The Anti-Western?

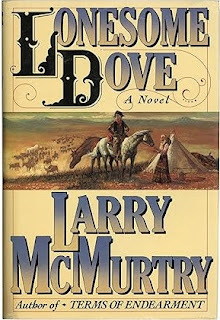

Socialmedia, I am told, is all abuzz these days with Larry McMurtry’s PulitzerPrize-winning novel, Lonesome Dove. While I lack even a passingacquaintance with the online exchanges, I have it on good authority that thebook is experiencing a resurgence, heaped with praise all the way up to andincluding being christened the greatest book of all time.

Much of the discussion revolves around Lonesome Dove being declared bysome the “anti-Western.” I’m not sure what that means. It may have to do withthe idea that McMurtry attempts to present a realistic portrayal of the OldWest, warts and all—a departure from the romanticized, glorified versionpopularized by Owen Wister, Zane Grey, Louis Lamour, and others, continuingright up to our time. (Not that those good-versus-evil tales with theirnecessary triumph of the good-guy hero are unusual in literature. The samepattern holds true at least as far back as Homer and the legends of King Arthur,and continues in cozy mysteries, thrillers, fantasies, private-eye novels, Westerns,and even much of literary fiction.) But somehow, calling Lonesome Dovethe “anti-Western” gives supercilious readers permission to read a Westernnovel—something their refined, sophisticated tastes would not allow otherwise.

But there is nothing new in Lonesome Dove’s attempt to present a raw,unvarnished version of the Old West. It has been done before and since, manytimes. Andy Adams tried it in 1903 in The Log of a Cowboy, a trail drivenovel that, unlike Lonesome Dove, grew out of the author’s personalexperiences.

Paso Por Aqui, penned by Eugene Manlove Rhodes in 1925, cannot bewritten off as glamorizing its subject. Nor can The Ox-Bow Incident byWalter Van Tilburg Clark, which has been turning the mythical Old West on itshead since 1940. Glendon Swarthout’s The Shootist (not the movie, whichpulls Swarthout’s punches) breaks all the expectations of the triumph of goodover evil. True Grit by Charles Portis also represents a departure.

A previous Pulitzer Prize-winning novel set in the Old West, Angle of Reposeby Wallace Stegner, presents a realistic view borrowed from the experiences ofreal-life Western transplant Mary Hallock Foote.

It would be difficult to depart from the romantic view further than CormacMcCarthy does in Blood Meridian and The Crossing, or E.L.Doctorow in Welcome to Hard Times. Loren D. Estleman’s Bloody Seasondemonstrates the dubious distinctions between heroes and villains. And while aglamorized view of the Old West peeks through in Ivan Doig’s Dancing at theRascal Fair and The Meadow by James Galvin, it is portrayed throughthe eyes of some characters, and is countered by the notions of othercharacters.

Are these examples—and others out there—“anti-Westerns,” or are they merelyWestern literature, sharing the stage with the broad range of plots, points ofview, and approaches that make reading good books of any genre a joy? I cast myvote for the latter. To me, Lonesome Dove is not “anti-Western” at all,but “pro” good reading and a great Western novel.