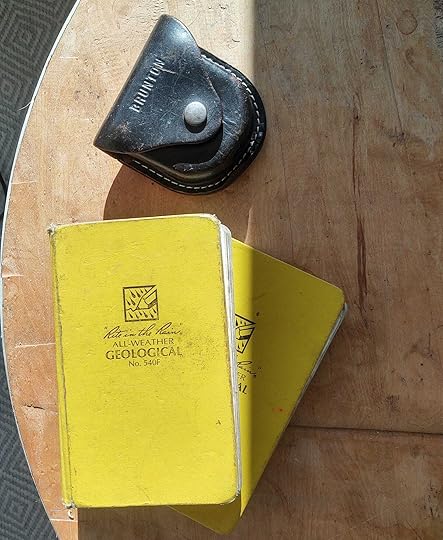

Rite in the Rain

"They look at mud and see mountains, in mountains oceans, in oceans mountains to be."

—John McPhee, Basin and Range

As a kid growing up in the Hudson Valley, I had a rock collection that I kept stashed in a purple box in my closet. The stones were ones that I had pocketed during recess or out on walks with my dog or on family hikes in upstate New York. The glassy herkimer diamond that my father had popped out of a boulder with his pocketknife and placed on my sweaty young fingertip while camping in the Catskills; the rusty beige slate, no larger than my palm, that I found on the bank of a muddy river and pocketed because it looked like the silhouette of a crow.

The shapes and textures of the rocks had drawn me to them, but I didn't see much to the stones beyond their physical beauty. I considered them as inert as the purple box that held them.

Sometimes I examined the crow-shaped rock in my hands before bedtime, tracing its contours with my fingers and inventing myths about the creature I saw in the stone. I had no idea that the rock contained traces of actual true stories more fantastical than the ones I was inventing. Stories of a time before beaks or feathers had ever shown up on Earth, when continents did not yet know breath or brains, let alone young girls making up stories before falling asleep at night. I had no idea that the stone was a piece of an ancient seafloor that opened windows into earlier versions of Earth.

Now, some three decades later, I can't look at rocks without trying to decode whatever narratives they hold. But it wasn't an inherent love of rocks that got me here; in hindsight, I think it was actually my love of stories that first drew me to geology.

Like most kids in this country, my geoscience education stalled out around the fourth grade. I learned the basics of the rock cycle, made model volcanoes that erupted with baking soda and vinegar, and then moved on to the biology and chemistry and physics classes we were required to take as we got older.

It wasn't until I arrived at college and stumbled into an event the Geology Department was hosting during my freshman year that I began to entertain the idea that I might actually like this field of science. Through a crowd of students eating pretzels and chatting with professors, I found myself drawn to a table with a pile of yellow hardcover books. I opened one and flipped through dozens of blank waxy pages followed by a collection of illustrations of sediments and timescales and map symbols in the back.

These books, I was told, were the Rite in the Rain field notebooks that I would need to purchase if I were to enroll in the geology classes offered that year. The waxy texture of the pages helped repelled water, so we could write on them even in the rain. While my other classes required heavy textbooks full of glossy charts and information that lacked any sort of narrative, these geology classes called for empty pages that we would fill with our own observations and craft our own versions of narratives of how we understood the world around us.

I enrolled in my first class not for the rocks but for these notebooks (and, of course, for the promise they held of spending time outside).

Before long, I declared myself a major, imagining building a career as a detective of deep time, filling my office bookshelves with dozens of yellow spines. But I also enrolled in poetry workshops and literature classes, and loved seamlessly floating between the worlds of science and writing, feeling how the one informed the other. How poetry came to me while peering at a mineral beneath a microscope lens and how geology came to me while working layers into my prose.

"They look at mud and see mountains, in mountains oceans, in oceans mountains to be," writes John McPhee in Basin and Range.

Only once I discovered John McPhee’s achingly vivid take on geology in Basin and Range did I realize that I could maybe exist in both these worlds, all of these worlds, at once. In the science and literature, past and present, lyric and literal. Maybe I could help make sure that others don’t miss out on the gifts of geology, just because they mistakenly assume it’s dull and boring. Because they still see rocks as inert objects, rather than the frayed fibers of our own beginnings.

Reading Recommendations

If you're looking for geology books beyond John McPhee’s classic Basin and Range (first published in 1981), here are some other more recent gems:

Timefulness, Reading the Rocks, and Turning to Stone by Marcia Bjornerud

Trace by Lauret Savoy

Becoming Earth by Ferris Jabr

When the Earth was Green by Riley Black — just published this week, I can't wait to dig in!

And last but not least — not a geology book per se, but one that I had the honor of witnessing evolve over the past few years and am so excited to see out in the world on April 8th! By the lovely and brilliant Chelsea Steinauer-Scudder: Mother, Creature, Kin.

Laura Poppick's Blog

- Laura Poppick's profile

- 24 followers