Paul Atkins: the Anti-GiGi. I Can Offer No Higher Praise!

SEC Chairman Paul Atkins has clearly set out to be the anti-Gary Gensler. If that’s not an endorsement, I don’t know what is!

Case in point–his move to abandon to the mercies of the courts Gensler’s cretinous, pointless, and incredibly burdensome climate reporting rule. (I use that Sierra Club link to provide some levity. I love the smell of hysterical panic in the morning).

Atkins is also largely reversing GiGi’s anti-crypto agenda. (Well, he is a “crypto peddler” after all, at least according to the Sierra Club!) I am not a crypto evangelist by any means, but broadly support letting consenting adults trade what they want to trade. The regulatory framework for such trading should focus on legitimate investor protection, anti-fraud, and anti-manipulation measures as set out in the SEC’s authorizing statutes. That’s what Atkins’ SEC is striving to do, in contrast to Gensler’s mission to strangle crypto at every opportunity.

In crypto, but more generally, Atkins is also moving sharply away from Gensler’s regulation by enforcement approach, which is another welcome change.

And hot off the presses, Atkins has taken aim at the bloated and (IMO) pointless Consolidated Audit Trail. (Seriously–I found the above announcement while Googling “Atkins CAT” while writing this post. It came out hours before I put pixels to screen). Proposed in the aftermath of the 2010 Flash Crash, it always struck me as a hugely expensive solution to a non-existent problem. Yes, the CAT could assist in forensic evaluations of market events like the Flash Crash and market manipulation, but having worked on such evaluations in markets lacking the CAT, and reading the analyses of others, I conclude it is possible to carry out these analyses without CAT. Put differently, the marginal benefit of the CAT is minuscule relative to the cost.

One issue that has received less attention outside the equity trading community is market structure, and particularly RegNMS. The 20th anniversary of that regulation was the occasion for an SEC conference to reevaluate that regulation. (At the time of the passage of RegNMS, I wrote an article saying that it marked the 30 Years War over market structure that began with the 1975 Securities Act, and wryly suggested that there would actually be a 100 Years War over market structure. We are now at the halfway mark!)

Along with several participants, Atkins criticized a key provision of RegNMS–the so-called “trade through rule” that prevents the execution of a trade on one exchange when a better price is displayed on another. Atkins favors elimination of the rule.

This rule is the keystone of RegNMS, and its removal would reshape the equity exchange environment as thoroughly as the regulation did 20 years ago. Indeed, its elimination would signal that the entire experiment was ill-conceived.

As I wrote in my Regulation Magazine piece, the trade through rule was the “centerpiece” of RegNMS. Its very purpose was to cause a fundamental restructuring of equity trading in the US. And it did.

As I phrased it, the purpose of the rule was to “socialize order flow.” That is, eliminate–or at least sharply circumscribe–the control that an exchange had over the order flow directed to it. The objective of this was to make the exchange landscape more competitive, and specifically to reduce the market power of the NYSE and NASDAQ. At the time of RegNMS’s passage, the NYSE executed 80 percent of the volume of shares listed on it.

Evaluated against its stated objective, RegNMS was a . . .

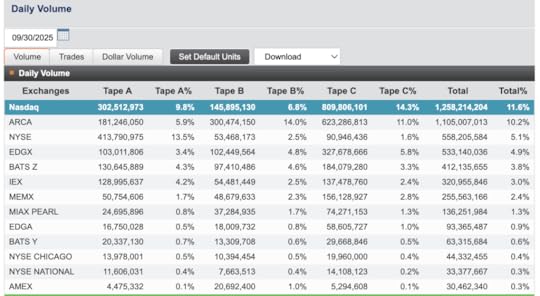

The equity trading landscape looks nothing like it did in 2005 or before. More than half of trades are executed off exchange. The remainder is divided among 12 exchanges, with the largest having a 10 percent market share:

But to Atkins and the critics of the trade through rule, this represents not great success, but great failure. To the critics, this fragmentation is deleterious.

That is, one man’s competition is another man’s fragmentation.

The post-RegNMS environment has clearly seen dramatic improvements in liquidity and declines in trading costs. This is plausibly, though not definitively, materially the result of increased competition. Moreover, the exchanges have adopted different order types, pricing rules (e.g., taker-maker/inverted v. maker-taker), and trading infrastructures. This means that heterogeneous market participants can choose among heterogeneous platforms, thereby achieving a better match than a one-size-fits-all system would.

The main disadvantage of fragmentation–and a major source of discontent–is that brokers and traders must connect to a variety of platforms, and crucially, must buy data from each. As I wrote some years ago, this creates strong complementarity among the data streams that exchanges provide, which as Cournot demonstrated two centuries ago creates considerable market power which inflates prices. Data is expensive, and economics implies it is too expensive.

What would happen if the trade through rule is abolished? I predict that by effectively re-privatizing order flow it would lead to a massive consolidation of trading venues, and a return to a market structure resembling that of 2004 and before. Less fragmentation, but less competition. Those are essentially two sides of the same coin.

The busy Mr. Atkins has also weighed in on the issue of the frequency of corporate reporting, favoring (fast-tracking, actually) the elimination of the quarterly reporting requirement. Since Trump proposed the same, of course this has led to shrieks and wails–which have been markedly absent when Warren Buffet mooted the idea.

Here’s another issue where I support letting the market decide, as is typically the case when there are trade-offs. Reporting frequency has costs and benefits. A company that provides too little information largely internalizes the cost, in the form of a lower stock price. That is to say, its shareholders internalize the cost. Yes, agency problems mean that managers who make disclosure decisions may act against the interest of shareholders and disclose too little or too infrequently, but that is a problem that is inherent in the corporate form (and the consequent “separation of ownership and control”) that manifests itself in many ways that are not the subject of government mandates and intricate regulations. It’s hard to see why corporate disclosure should be different. Yes, punish false disclosures, but don’t dictate how often companies must avoid lying.

One concern in recent years has been the large number of companies deciding to go private or remain private (rather than IPO’ing). There are myriad reasons companies make these choices, but one of them is the cost of being subject to the reporting obligations imposed on public companies. Easing those obligations somewhat would nudge more companies toward going/remaining public, meaning that the amount of information available to investors and the opportunities available to them might increase if the Trump/Atkins proposal goes into effect.

Overall, Atkins is a welcome relief. Though anyone probably would have been, after Gensler’s Reign of Error (and Terror). I’m ambivalent about his hostility to the trade through rule, but on non-market structure matters he is moving in the right–and pro-market–direction.

Craig Pirrong's Blog

- Craig Pirrong's profile

- 2 followers