[2025 Re-Post] Rigor Shouldn't Lead to Mortis

I have been in lockdown for the past two weeks, working on assessment items for an academic Olympiad and trying to help both an LLM and a team of human subject-matter experts get better at crafting questions that demand high levels of cognitive skill…more rigorous items, if you will. And since I don’t have time to write anything new this week, and the idea of rigor is front-of-mind, I thought I’d re-share this post from two years ago.

The Challenge

Once upon a time, I attended a meeting of Chicago teachers, back when Arne Duncan was CEO of the public school system there. He was advocating a new plan for a standardized but somewhat decentralized curriculum (schools could select programs from a menu of approved vendors), and he was talking up how this plan would increase academic rigor. Whereupon, some teacher in the crowd stood up and yelled at Duncan that the CEO had no idea what “rigor” actually meant, and neither did anyone else in the room, and if anyone thought they did know, it was a good bet their definition wasn’t shared by anyone else in the district, or in the education world more widely.

I don’t remember what Duncan’s response to the heckler was. It was probably ham-fisted and vague and ineffectual—which would not be surprising. Rigor is one of those words that people love to toss around without really knowing what it means. As Supreme Court Justice, Potter Stewart, famously said of obscenity, we know it when we see it. As pretty much everyone has said of beauty, it’s in the eye of the beholder. But should it be? Must it be?

A Healthy Workout

The easiest (and dumbest) way to think about rigor is in terms of quantity: just give kids more to do. I say it’s the dumbest because, if students are doing a certain amount of X successfully, it’s not rigorous to simply do more X. It’s not even particularly helpful. It’s just tedious.

If a trainer is going to put me on a rigorous workout regimen, is he going to have me lift the same amount weight every day, forever, just adding more and more reps? He is not. I’m sure there’s probably some benefit to adding reps to your current weight-load. Stamina? I don’t know; I’m not a trainer. but if you’re trying to build muscle, people tell me, you have to lift increasingly more weight. The lift has to get harder over time. You lift what’s just doable, and you work on that for a while, until it becomes easier. Then you add more.

Even the least gym-ratty among us should be able to recognize what’s going on here. In edu-speak, we call it the Zone of Proximal Development, or ZPD. It’s that sweet spot—Goldilocks’ “Just Right” place—the most difficult level of work that a student can do comfortably. It’s where we would like every day’s classwork to be situated, for every single student. Difficult to do, when every student is in a different Just Right place. And more difficult still when, like the guy lifting weights in the gym, today’s Just Right place changes over time. To maintain rigor, you have to know exactly where a student is, and situate the work right at the leading edge of that ZPD. It’s a serious challenge.

What Matters Most

What does it mean to know “where a student is?” In math (and sometimes science), you can assess knowledge or mastery of discrete topics and skills. In the humanities, which is less modular and discrete, it can be trickier. Once you can read at a high Lexile level, you’re a skilled reader. Once you can write at a collegiate level (or close to it), you’re a skilled writer. What constitutes “harder?”

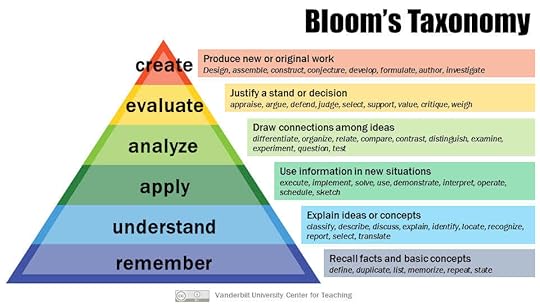

When we want to increase rigor and push students to go further, we often increase the cognitive complexity rather than just accelerating them to the next topic. Benjamin Bloom’s taxonomy provides a handy guideline for teachers, showing factual comprehension as a base level, and working up through analysis to evaluation and, ultimately, creation of new content. This can help teachers take the same set of content and change what kind of work is expected of each student.

Richard Strong, Harvey Silver, and Matthew Perini, in Teaching What Matters Most (ASCD, 2001), go further , describing rigor as, “the capacity to understand content that is complex, ambiguous, provocative, and personally or emotionally challenging” (p. 7). It’s an interesting construction. The authors aren’t satisfied with mere complexity. They want students to be able to handle ambiguity and provocation—not merely theoretical provocation, but material that challenges the student personally.

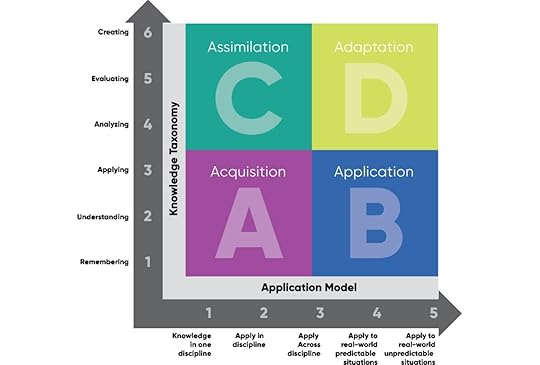

Ambiguity is also an important element of the Rigor-Relevance Framework, developed by Bill Daggett. The framework creates a quadrant map, with Bloom’s Taxonomy forming the vertical axis, showing increasing cognitive complexity, set against a horizontal axis that speaks to application—starting with knowledge and use within one classroom discipline, then moving to application across disciplines, then going outside the classroom into real-world but clear and predictable situations, and landing, finally, at real-world application in a messy, unpredictable situation. For Daggett, real rigor is the ability to work at the highest cognitive levels (evaluation and creation), in the messiest and most ambiguous contexts.

Getting Stronger Every Day

What is the result of a rigorous physical workout regimen, sustained over time? You build muscle. Your body changes. It is no longer what it was. If we worked with a trainer for a year and saw no physical change in ourselves, we would be dissatisfied.

What is the result of a rigorous education, sustained over time? You build mind. Your thoughts change, and the way you think changes. You are no longer what you were. If the child moves from one grade to the next and has not grown and changed in what she knows and how she thinks, even a little, parents should not be satisfied.

And yet, it’s exactly that kind of growth and change that has been the focus of parents’ ire and activism in recent years. God forbid the school should provide opportunities for students to challenge their preconceptions, to broaden their understanding of how the world works. Somehow, we’ve been led (or forced) to believe that what a child thinks and how a child thinks are…none of our business as teachers. That the content of a child’s mind is the sole responsibility of the home and the church, and that the school’s job is merely to reinforce and strengthen whatever ideas and opinions the child comes in with. Apparently, we are supposed to provide a variety of safely vetted facts, and hone a variety of state-mandated skills, but we must ensure that the child never actually changes her mind or her opinion about any of those facts, or applies those skills to develop her own ideas.

This is dangerous nonsense. A nation that is afraid of looking at things from a different angle, considering things from a different perspective—is a nation that is calcifying. A community that is afraid of its children learning facts that their parents might not have learned, or developing opinions different from those of the adults—is a community that is frightened by a changing world (which is the only world we have).

We are better than that. Or, rather, we should be better than that. If we want our children to inherit a strong and dynamic country, we must be better than that.

Scenes from a Broken Hand

- Andrew Ordover's profile

- 44 followers