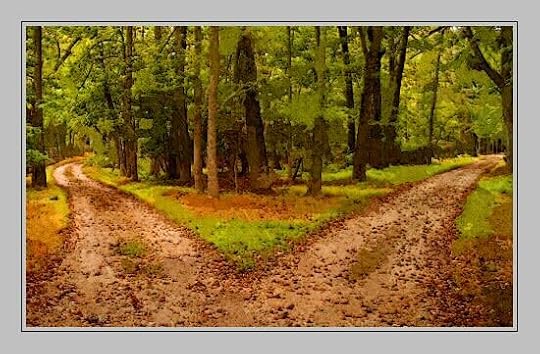

We Make the Path by Stumbling

I came to ambition late in life, although I had plenty of delusions as a child. I thought I was going to be a famous novelist, and then I thought I was going to be a famous playwright—unclear what it meant to be a working professional in either of those fields, much less a famous one.

I wonder sometimes, what did I think it meant to make a living, back when I was a child? How did I think the game was played? What did I think was required of me? What did I think I was supposed to do?

I didn’t have a clue. I don’t think I even had a clue that I didn’t have a clue.

What Was College For?I grew up in a high-pressured, college-prep school system; higher education was the focus of everyone’s attention, and the right college was everyone’s goal. There were families in my town that bribed their kids with cars if they got a good score on the SAT. There was a family that had a ranking system of cars as part of the bribe: hit this score and you get this car; hit that score and you get the BMW. I am not kidding.

We had four valedictorians in my graduating class. Four. And they all had to make speeches. Because of course they did.

I don’t remember a single word that any of those four lovelies spoke; all I remember is that the sound system was shot, and there was a van parked next to the podium, with a couple of big guys crawling around trying to fix the microphones. It did not occur to me at the time that those guys were performing a more important service than the four, smug students who were making speeches about things they knew nothing about.

The idea that someone might not get into college was just…unheard of. Un-thought of. There was an unspoken understanding that if you got yourself into the Right School, everything else would flow like the sweet waters of heavenly justice.

I think.

I’m guessing here; no one ever said those words around me. I think my town was so over-represented by the Professional Class that the glide-path from high school to college to grad school to some kind of career was just assumed.

There are certain things in your culture or class that are so universally understood that they never have to be spoken—and those are precisely the things that can fuck you up.

I did not have excellent grades. I had good grades in the classes I loved, mediocre grades in the classes I liked, and rotten grades in math and science (and French, though for some insane reason, I kept taking it long after I had to). My grade-point average was average, but I was a good writer, and I seemed to show some Leadership Potential in my chosen extra-curricular activity, so I got into some good schools. More than I had any right to, probably.

When I say “more…”

In my town, it was standard practice to apply to many colleges—seven, eight, nine, whatever. And this was before you could access the Common Application online, or type in a PDF form, or anything like that. Every application had to be handwritten or hand typed. When I got to college and found out that kids from other parts of the country had applied to only two or three schools, I thought they were all crazy. Eventually, I realized that I had been the crazy one. But it took a while.

I have no regrets about my liberal arts college experience, as I wrote about recently. But it’s inescapably true that no one engaged me in a discussion about what was going to come after. Not one person, ever.

In this, I was clearly an outlier. It was 1985, and everyone had a plan. Everyone. Even the kids who were doing theater with me had post-graduate plans—for law school, or business school, or some PhD program somewhere. Everyone knew what was coming next but me.

Not quite as bad as Dean Wormer’s admonition to young Flounder, but…close.

How Pathy Was My Path?It’s not like I hadn’t thought about it. Of course I had. I had decided that theater was going to be my thing, which made the whole idea of a “career path” kind of fuzzy. How did one get a career in writing or directing? By…just doing it, I figured. So, I did as much of it as I could. Meanwhile, I tended bar (very briefly), I worked in a bookstore (for a year), and, eventually, I taught school. These were all merely “day jobs,” ways to make money while I pursued my dream. A temporary state of affairs that went on for about 15 years.

Here’s what I learned from those 15 years: I learned that you could make things happen through your own sweat and effort, but that making a thing happen once was no guarantee that a thing would happen twice, or ever again. The world was willing to let me raise money and bring people together to stage a play, but once that play closed, it was back to square one. I had no more money for round two than I had started with in round one; I had no more reputation, either. Anything I did was a drop in an enormous ocean. Getting someone else to stage a play I had just mounted was a game whose rules seemed arbitrary and changeable.

I received some lovely rejection letters. Even when people thought my work was good, it wasn’t quite what was wanted. Other, more talented people prospered. Less talented people prospered, too. People who had friends in the right places prospered. People whose work focused on a currently hot topic. People who wrote from the perspective of a previously silenced group. Everybody but me, it seemed. I could tell I was getting resentful and peevish about it all, as though The Arts owed me a living. As though anyone did.

Did I hustle? Did I grind it out to try to get ahead? At the time, I thought I was doing that. I sent plays and synopses and query letters to agents and theaters all across the country. Real letters, printed out and folded and stuffed and stamped. I followed up on each letter without becoming a pest. I thought that was hustling.

What I didn’t do was get out of the bubble of my little theater company and schmooze. I didn’t network. I didn’t work the room. I didn’t make myself known and wanted and indispensable in the larger community. Frankly, I didn’t know how. In our company and among my friends, I was the writer in a sea of actors—the token introvert—the guy who disappeared from parties after an hour and slunk home in silence. That guy. I played that role well, but I didn’t know how to get cast in it in other productions.

So, Fine: Be a TeacherPart of the time while I was working with my little theater company, I taught high school English. If I gave up on theater, I could always focus on teaching. It was a profession! Just the kind of thing my old hometown would have wanted me to pursue, right?

Wrong. I went to a high school reunion at some point early on, and I discovered that literally no one in my graduating class was involved in education at any level. They had been trained since birth to start strong and never stop climbing. And when you’re a teacher, well…

Do you know what you get if you’re a brilliant teacher in a public school, a really first-rate teacher, with greater instructional skills than your peers, and a stronger work ethic, and a greater dedication to your students than anyone else in your school (not that I was any of those things)?

Nothing. You get nothing.

Well, that’s not true—you get satisfaction. You get a martyr’s sense of mission. You are invited to kill yourself for the sake of others, and you will be told that it is a great and noble thing. Which it absolutely is. But what you won’t get is a raise or a promotion based on your effort. Those things don’t exist in public school, and you will be shamed for even thinking about them.

Raises? Public schools tend to be union shops, where salary levels are fixed and immutable. If you have an advanced degree, you’ll make more money. If you have more years in the system, you’ll make more money. And that’s it. Performance has no bearing. The very idea of “performance” in that world lies somewhere between strange and disreputable.

Promotion? There’s no such thing as a “promotion” in most schools. Maybe there’s a senior teacher role, or a department chair role. Often not. In most cases, a teacher is just a teacher. If you want to do better for yourself and your family, your only road up is out of the classroom into administration.

By the age of 30, everything in my work-life had taught me that when it came to external rewards, it didn’t matter and was never going to matter how hard I worked. I could feel pride in what I did and satisfaction in its effect on audience members or students—and those things mattered quite a lot—but monetary success would always be controlled by strange and arbitrary forces beyond my understanding—and it was dirty and shameful of me to be concerned with those things, anyway.

I lived reasonably comfortably within that reality for a while. And then I got married, and a few years later, we had a child. And it was time to take another path.

So, Fine: Get a Regular JobWhen I started working in Corporate America: Education Division, I was shocked to learn a number of things: I could leave my desk to go to the bathroom, get a cup of coffee, or schmooze with a colleague pretty much whenever I wanted to. I could leave a room without asking for permission! This was unreasonably pleasing and surprising to me.

Also: I could do good and meaningful work that benefitted students and teachers, even though I worked for a company rather than a school. I could work for people who believed in “doing well by doing good.” To be sure, that wasn’t always the case; there were other places and other people where a sense of mission was sorely lacking or was just lip-service. But sometimes, in some places, everything clicked.

Also: if I worked hard and the company did well, I could get raises and occasionally bonuses. That didn’t suck, since I was trying to raise a family and was sometimes the only breadwinner.

Were the Curriculum world or the Virtual Ed world or the EdTech world true meritocracies? Weeeelllll….you know…..of course not. But they felt more meritocratic than any place I had worked before.

I started my post-theater and post-teaching career in a very small division of a very large company, and as the division grew, I was able to rise within it. I learned how to ask for what I wanted and hustle for it—certainly more than I ever did, writing letters into the void.

Why was I able to do that for other people’s products and not my own writing? Why is that still the case, even now? I don’t know.

I do know that many of the skills I have used in my corporate jobs, I learned by doing theater—as I’ve written here. If I understand curriculum, it’s because I understood storytelling and holding the attention of an audience. If I understand team management, it’s because I produced and directed plays, and worked under a variety of directors (good and bad) to watch how they did it.

Is this the realm where I thought those skills would pay off? It is not. But when I look back at my path in life—a path I never saw laid out in front of me, but which I can see clearly now behind me, it almost looks like it was inevitable.

Almost.

Scenes from a Broken Hand

- Andrew Ordover's profile

- 44 followers