Alice Wong

Alice Wong, Asian American woman in a wheelchair with a tracheostomy at her neck connected to a ventilator. She’s wearing a pink plaid shirt, pink pants, and a magenta lip color. She is smiling and behind her are a bunch of tall prehistoric looking plants. Photo credit: Allison Busch Photography.

Alice Wong, Asian American woman in a wheelchair with a tracheostomy at her neck connected to a ventilator. She’s wearing a pink plaid shirt, pink pants, and a magenta lip color. She is smiling and behind her are a bunch of tall prehistoric looking plants. Photo credit: Allison Busch Photography.I found out late Friday night that Alice Wong had died an hour earlier in a San Francisco hospital. Others will write better obituaries, finer eulogies, but Alice—the woman herself, the activist, the co-conspirator, the mentor and encourager—had an outsized impact on my journey through to and understanding of my identity as a Disabled writer.

We met on Twitter. I long ago deleted my Twitter account and archive and so can’t trace the exact beginnings, but I think it was probably sometime in early 2015, after she has started the Disability Visibility Project and I was beginning to accept that elbow crutches were no longer sufficient to living a full life: that it was time for me to investigate, buy, and start using a wheelchair. I could feel my own resistance to that, and I knew it was ridiculous. I’d already been talking to Riva Lehrer, so I was already waking up to it, but it was reading the conversations with and/or facilitated by Alice in various venues that really helped me begin to wrap my head around how the tentacles of ableism didn’t affect just my immediate day-to-day life but were coiled about and strangling almost every aspect of disabled peoples’ lives, including—especially—our interactions with the world.

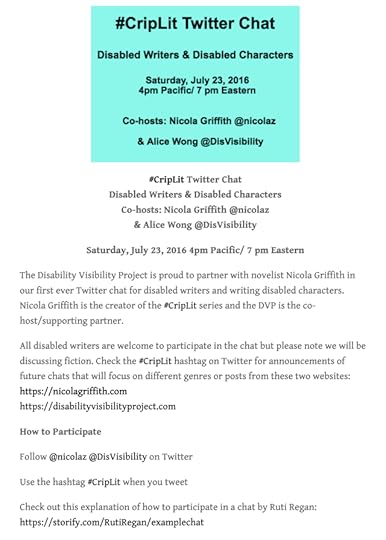

This of course includes our cultural lives. Alice and I were chatting on Twitter about writing: disabled writers, disabled characters in fiction. ‘We need a hashtag,’ I said. And #CripLit was born. Within a few weeks, Alice—the organisational powerhouse behind so very many crip community efforts of the early 21st century—and I were ready to announce the first-ever #CripLit chat for 23 July 2016. We announced simultaneously on here and on The Disability Visibility Project:

From the very beginning the chat was massive—almost overwhelming. Each chat took a lot of work to prepare—finding occasional co-hosts, working out the questions, scheduling, the intensity of the moderation—but they were worth it. We did one every couple of months for two and half years (they are archived here).1 I firmly believe that those chats moved the needle regarding disability literature. And though the hashtag and idea were mine, it was Alice—her drive, her organisational ability, her sheer forward momentum and refusal to let any barriers stand in her way—who made it possible; it was her energy that was the spine.

Alice was one of my two crip godmothers.2 She was fourteen years younger than me but decades wiser in the ways of disability, ableism, and the power of community engagement. I learnt from her constantly—sometimes in long conversations where I asked many (I’m guessing, looking back, rather tedious) questions, and sometimes just from watching how she handled situations. Alice was smart, brave, clear, definite, kind, and able to able to focus on and lead others to those from whom we can find and draw hope–because it’s hope that sustains us in hard times. Rage is vital—crip rage is powerful; and, oh, we have so much to be angry about—but Alice understood that it’s as important to talk about joy as about difficulty. It helps to be reminded of the positive things we’re fighting towards, not just what we’re fighting against. We don’t just want access; we don’t just want representation; we want power, real power over ourselves and our lives.

When I wrote So Lucky, Alice was kind enough to interview me for her blog.

We connected on Twitter several years ago and are co-partners in #CripLit, a series of Twitter chats about writing and disability representation with a particular focus on disabled writers. What have you enjoyed so far from these chats? Why do you think there is a need for these types of conversations? What do you see for the future of #CripLit?

Nicola: What I like best about #CripLit is a building sense of excitement, the disability community come together and beginning to flex. We are 20% of this country, maybe 20% of the electorate. We are amazingly diverse and fine. There are some incredible groups coalescing around different focuses; social media is a powerful way to connect. #CripLit is just one of them. Now we need to find a way to bring all these groups together to form a critical mass, a tipping point. We need to catch fire, to join in a roaring, creative inferno, to pour forth.

Part of that is to start putting together the scaffolding we need to build cultural connections; that scaffolding is story. We don’t know who we are until we can tell a story about ourselves. Stories help us understand we are not alone.

But to write stories we need to know that we’re not just a voice crying into the void: that others are crying out, too. Once we know others are there, to help, to learn, to teach, to support, we can sing out in harmony, build a chorus that will change the world.

That’s what #CripLit is for.

When she published her anthology of essay of crip wisdom, Resistance & Hope, I returned the favour and interviewed her here. I really hope you’ll go read that interview. It is pure Essence of Alice.

As a disabled activist and media maker, who or what are you most determined to resist? And where do you find hope?

I resist policies and programs that keep disabled people from living the lives they want. I resist low expectations and tokenistic attempts at disability diversity by organizations and institutions. I resist the feelings of shame and isolation that still plague many of us, including me. I resist the idea that nothing can change and that every system is broken. I resist the idea that representation is enough when what we really want is power.

I find hope in my friends and family. I find hope in the amazing ways disabled people create and get things done interdependently. I find hope and joy in the simple things—excellent conversations and meals. And cat videos.

I miss Alice, her clarity, bravery, and joy. I wish she were still here, but her work continues.3

Sadly, all my tweets are missing because when I deleted my Twitter account I also deleted the archive. That missing record is the only thing I regret about leaving that platform. ︎The other is Riva Lehrer. I’ve talked about Riva often, and will no doubt do so again.

︎The other is Riva Lehrer. I’ve talked about Riva often, and will no doubt do so again.  ︎Her family has committed to continue her work, so if you wish to contribute to that, please donate to her GoFundMe, which was originally started to help keep Alice living in the wider community.

︎Her family has committed to continue her work, so if you wish to contribute to that, please donate to her GoFundMe, which was originally started to help keep Alice living in the wider community.  ︎

︎