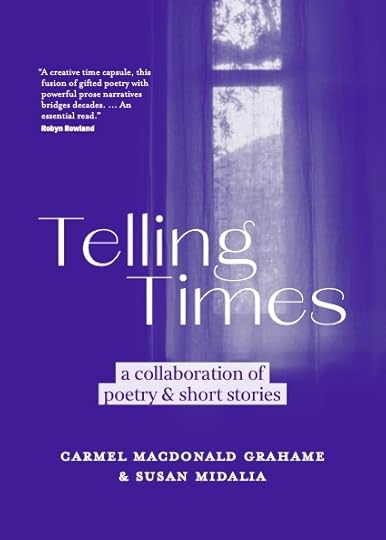

Telling Times

Telling Times

Carmel Macdonald Grahame & Susan Midalia

Short fiction/poetry

2025; see end of post for availability

It is a great pleasure to read anything written by Susan Midalia or Carmel Macdonald Grahame, so to find them together in a volume of their own is a rare treat. Telling Times is unusual in being a collaboration of two writers writing in two genres, with a common purpose.

I’ll let the book’s back-cover blurb elucidate this further:

From beauty pageants to experiences of war, Telling Times charts the lives of women and girls in the context of crucial events and political movements that have shaped the modern western world. Its ethical lens is trained on subjects as varied as education, migrant experience, domestic violence, the movie Titanic and the effects of contemporary technology. Acutely observed, and with a keen sense of social justice, Telling Times takes readers from the 1950s into the new millennium, where the plight of asylum seekers and awareness of climate change begin to shape a sense of our future.

Carmel Macdonald Grahame’s short fiction, poetry, critical essays and reviews have appeared in literary journals and anthologies in Australia and Canada, and her novel, Personal Effects, was published by UWAP in 2014. Her most recent publication is Angles, a poetry collaboration with Karen Throssell. Carmel currently lives in Victoria.

Susan Midalia is the author of three short story collections, all shortlisted for major national awards—A History of the Beanbag, An Unknown Sky and Feet to the Stars—as well as two novels, The Art of Persuasion and Everyday Madness. Her latest publication is Miniatures, a collection of flash fiction. Susan lives in Perth.

I was delighted when Susan and Carmel agreed to tackle a barrage of questions from me.

AC: For the benefit of those who have not had the pleasure of hearing the two of you speak about the genesis of Telling Times, could you please sketch out how this collaboration came into being?

CMG: Susan and I have been friends for years. When she sent an email suggesting we exchange work, we initially thought of it as a writerly exchange, an exercise if you like, for me during a protracted Melbourne lockdown. The invitation was a wonderful way of spending time that had begun to feel quite lost. As we exchanged work, the idea grew that we might make something of it; that our retrospections had a point to them. The structure grew out of our correspondence, through emails, phone calls and some face-to-face meetings, about this sense of the relevance of the work.

SM: As Carmel said, the collaboration was a way to help Carmel endure months of lockdown, but I was also in need of some stimulation and encouragement after months of not writing a thing. All writers have these fallow times, but I was feeling increasingly moody about my lack of productivity. So the collaboration helped both of us get into the swing of writing again and to keep refining our writerly and editing skills. And we’re still great friends after the process!

AC: The book is a bold, beautiful hybrid in terms of genre, combining Susan’s short stories and Carmel’s poems. I have a couple of questions regarding genre, the first for Carmel. When I first met you, many years ago, you were a prose writer. I remember your powerful short stories (I can vividly remember you reading one called ‘Slack Key Guitar’), and of course there is your beautiful novel, Personal Effects. Has there been a particular impetus for your turning towards poetry or was it just the right vehicle, for you, for this project?

CMG: I’ve always most enjoyed short forms and I find the short story a rich genre. It requires us to write economically into a situation, an experience, a relationship, and to find ways of opening it out internally to suggest circumstances beyond the story itself. It’s a writerly challenge I’ve always enjoyed trying to meet, deeply pleasurable in fact. Economy of form makes particular demands, doesn’t it? As does poetry of course, which is even more finely wrought in that you most often come to it with a preexisting sense of form. In both cases it has something to do with taking pleasure in the intricacies of the work. I think of it as a kind of embroidery. I enjoy the essay form for the same reason: there’s an internal logic you are hoping to stitch together in language. You are always finding the language to give expression to an idea, are you not? Was it Mallarmé who said poetry is made of words, not ideas—a favourite quote of mine—meaning that language is the stuff with which you’re working, your paint if you like. I wrote my novella as a personal challenge to see if I could bring the same sustained attention to creative work as I had previously applied to the writing of academic work, like writing a thesis. I wanted to try that deeper immersion into storytelling, but the sprawl of the form and the time it takes to achieve it are not for me. I’m a miniaturist, I guess.

AC: And Susan, I’ve never known you as a poet, although your prose is often undoubtedly poetic. Can you see yourself ever inhabiting that space?

SM: As you suggest, Amanda, the line between poetry and prose is porous. Both genres, at least in their modern forms, rely on compression, implication and concision. Both can have a narrative impulse, and both can use imagery, metaphor and the musicality of language. But on those few occasions when I’ve attempted to write poetry, it always read like chopped up prose: banal, predictable, dead. What draws me to prose is a fascination with the psychology of character (although the poetic form of the dramatic monologue is a study in the ambiguity and complexity of an individual). I enjoy imagining creating the inner lives and the voices of different characters, and not always sympathetic ones: individuals of different ages, genders, cultural backgrounds, temperaments and values. Although I’ve published two novels, my heart lies with the short story form, because it reminds me that we experience our life in terms of moments in time: a crisis, a turning point, a revelation, the realisation of intense disillusionment, a brief moment of unalloyed joy. I also love striving to combine economy and evocation, brevity and depth, in ways that I hope readers will find satisfying, and I’m drawn to the use of the unsaid—what cannot or must not be expressed—that often characterises short stories. It reminds us that life is always a contest between the spoken and the silent, the known and the unknown. It also encourages readers to read between the lines, as it were; to be active participants in the creation of meaning, instead of passive recipients.

AC: Telling Times uses decades (1950s–2000s) as its structuring/thematic logic, and I’ve heard you both say, quite forcefully, that its focus is not nostalgia; that it has, rather, an anti-nostalgia focus in the sense of questioning, critiquing, laying bare those times. For example, the title of the 1950s pieces, ‘The Good Old Days’, is used in a deeply ironic way, in stark contrast to the way that phrase is sometimes invoked by certain politicians and others wearing rose-tinted glasses. Tell us a little about some of the issues your pieces speak to.

CMG: Just to take two examples—It seems to me that a decade like the 1950s is often idealised, probably in the wake of World War II. In fact, when I scrutinise it, I come up with childhood memories of an often-cruel education system, unleashed child abuse, ugly prejudice against migrants who were arriving in great numbers, deep institutional misogyny, and a culture profoundly riven by sectarianism. I try to take a child-perspective of what I observed and experienced around me and to tell it as vividly, as true-to-life, as I can. This impulse is at work in poems like ‘Telling Times’ and ‘The Red Phone Box’. Later, in the 1980s say, a changing and unscrupulous workplace culture became evident as economic rationalism took hold. I engage with my memories of this in the poem ‘Zeitgeist’ that opens the decade. The AIDS crisis occurred during which homophobia and a self-evident lack of basic compassion in response gripped the world. Chernobyl and technologies of various kinds began to give us the sense of a threatened planet, President Reagan and his Star Wars defence not least. Retrospectively it felt to me like the decade when optimism waned in some global way.

Both the stories and poems are rich with details and features of each decade that we do celebrate, but the driving impulse was to resist nostalgia and keep track of what we saw as significant and sometimes disheartening changes. I suppose it amounts to a skewed form of memoir, and the collaboration and hybrid form allowed us to be comprehensive and agile in our retrospections.

SM: Like Carmel, I’ve used the perspective of children in the 1950s section of our book to expose the rigidity and cruelty of teachers; to reveal the racism and xenophobia of a period of history which white Australians still refer to as ‘the good old days’. A couple of the stories in that decade are heavily autobiographical: ‘Fitting In’ and ‘Dictation’ (although the latter is deliberately hyperbolic…I had no intention of being subtle!). The child’s perspective can be a particularly engaging one, combining as it often does raw emotion and a naivety about the actions and beliefs of the adult world. And while some of the details in the book about fashion, objects, food, will give older readers the pleasure of recognition, one of our specific aims was to undercut stereotyped and sometimes romanticised ideas about the past. As another example: the 1960s in Australia is still often viewed as socially and morally progressive: all that sex, drugs and rock and roll (alas, that wasn’t my experience as an adolescent). While the hippie culture was becoming more visible, the country was still in the tight grip of conservative forces. Rape within marriage was legal; abortion was illegal under any circumstances; male homosexuality was illegal; domestic violence was typically ignored by the police—regarded as a ‘personal’ matter between husbands and wives. And as some of Carmel’s later poems and my later stories suggest, while there undoubtedly has been some progress, prejudice and bigotry persist.

AC: The stories and poems have a distinctly Western Australian flavour, and many cultural references that will be especially satisfying for readers who live or have lived here. (My own favourite is the reference to the House of Tarvydas. How I longed, at fifteen, to be cool enough, or able to afford, or even to have an occasion I could wear, a Ruth Tarvydas dress!) What was your thinking in taking this approach?

CMG: My thinking was to pay attention to significant events and the flavours of each decade, to try to capture a kind of atmosphere that is particular to a place—it’s in the detail really. Tim Winton, Elizabeth Jolley, so many more, have firmly imprinted our local setting on the literary landscape. Western Australia continues to be my country, although as life has gone on, I’ve had to be mobile. I wanted to acknowledge historical circumstances that have been a part of my experience and tell it as I see it from that vantage point. Without fictionalising, and by weaving personal and observed circumstances together, I tried imaginatively to reinhabit the times and places in which I’ve lived. And for much of that time I lived in Fremantle. Heartland.

SM: I spent my first ten years living in seven different towns in the West Australian wheatbelt—my father was a salesman who was always in search of a ‘better’ job. I think the experience left me with a deep sense of dislocation; a feeling that I didn’t really ‘belong’ to any one place; a feeling exacerbated by being the child of postwar European migrants. I’ve tried to capture that sense of living in Western Australia in two stories set in the 1950s. What has always interested me as an adult living in Perth is Western Australia as a political, rather than a physical space. My natal family always talked politics, sometimes ferociously so (as in my story ‘Dirty Commie Bastards’), and I have continued to do so with my children and with friends. I wanted to capture the ‘flavour’ of some major events in my adult life: the passion of ideas, if you like. The Vietnam War, the AIDS crisis, the Lindy Chamberlain case, the Bicentennial celebrations, for example.

AC: Still on the subject of Western Australia: Carmel, I’m wondering what it was like to write about your former home from a geographical (as well as temporal) distance. Do you think it made any difference? Gave you a different perspective?

CMG: I do. Time and distance have made my sense of the where-and-when more comprehensive perhaps than would otherwise have been possible for me—the view from outside can be panoramic, so they say. I think writing about anywhere after you have left it somehow illuminates your experience of it. At the same time, since I have a sense of distilling personal experience and trying to blend it with things I have heard from other people, it was inevitable that my early focus would be WA. It anchors my thinking. I also wanted to celebrate Western Australia, to make it sing in parts of the country where it seems to me under-sung.

AC: Susan, if musicality is one characteristic of your prose, another is humour. How important is humour in this collection, and in your work generally?

SM: Humour in this collection is a vital part of the way I respond to the injustices and cruelties of the world. As Oscar Wilde famously quipped: ‘Comedy is the most serious form of literature.’ We laugh or give a wry smile, and then we think about why we’ve reacted in this way. Sometimes I’ve used satire—the deliberate use of exaggeration—as in my story ‘Dictation’ to expose the sadism of a teacher. The satiric story ‘Topical’ takes form of an interview in which a homophobic politician’s responses to questions become increasingly ludicrous, unhinged. I’ve also used techniques such as incongruity, juxtaposition and the form of a questionnaire to make fun of the Australian public’s warped priorities: for example, choosing Queen Elizabeth’s visit as more important than the return of Vietnam veterans. Apart from using humour for ethical and political purposes, I also wanted readers to have a laugh at the absurdities of life. If I believed in reincarnation, I would like to come back as a stand-up comedian (without the heckling). I can think of nothing more joyful than making a room full of people laugh.

AC: Carmel, while listening to you speak about the past, I was struck by your comment about belief: that in those earlier times in your life, you had the absolute belief that it was possible to change the world through activism, through alternative ways of living; that you were going to achieve it. The poem ‘Season’ (1970s) beautifully conveys that kind of optimism. I’m wondering what it was like to write that in hindsight.

CMG: To be honest it was partly driven by a sense of disappointment and a growing sense of disillusionment. I remember a time of confidence in ideas like answers blowing in the wind…It’s Time…Give Peace a chance…etc. We tried to create communes, live in alternative ways, send our children to alternative schools and so on. Protesters chained themselves to trees. There was a burgeoning environmental movement. Women’s refuges were set up in the hopes of finding solutions to misogyny and family violence. Refugees were welcomed after the Vietnam War. And so on. There was a sense of forward momentum, possibility, potential. There is a growing sense among many of my contemporaries of wheels being reinvented and old ground being gone over, of past efforts being dismissed rather than furthered (the old idea of standing on the shoulders of those who came before seems to have been ‘influenced’ out of existence), and above all peace most certainly has not been achieved. It feels now that a world we thought possible—so idealistically—has slipped below the horizon. Poems like ‘Of States, Of Mind’ and ‘Invasion Eve Protest’ are underpinned by this sense of disillusionment.

AC: Susan, I love the companion stories ‘And Here is the News for 2001’ and ‘And Here is the News for 2009’, which combine satire and serious comment in an unusual way. Could you talk, please, about the way you put these stories together?

SM: These two stories, which book-end the final decade of the collection, are fundamentally concerned with the inhumane treatment of asylum seekers and continuing inaction on climate change (both of which, to my despair, remain with us today). Both stories use the form of a news broadcast in which the seemingly endless repetition of headlines and soundbites about those two issues draws attention to the fact that politicians and the general public keep denying responsibility for addressing, let alone trying to resolve, the problems. Using the form of a news broadcast also allowed me to cover a whole range of other items: from the important, like the attack on the Twin Towers, to the trivial, like the popularity of distressed skinny jeans. It was a way of suggesting that the daily diet of news can ultimately reduce everything to the same value. I’ve also mixed fact and fiction to, for example, satirise misogyny: the then Deputy Prime Minister Julia Gillard being vilified as ‘deliberately barren’ (a real statement made by a conservative politician) and mocked for her new hairstyle being ‘too masculine’ (fictional). Another example is the announcement of the First Nations movie Samson and Delilah as the winner of the 2009 Australian Film Industry Awards (a fact), followed by an invented comment from a politician about most Australians being ‘fed up to the teeth with all this rubbish about so-called Indigenous so-called disadvantage’. I’m so glad you enjoyed these two stories, Amanda, because I feared that the barrage of lists might merely frustrate the reader, when part of my point was for them to experience the frustration of continuing injustice, bigotry and political self-interest.

AC: You have been quite open in talking about the lukewarm/non-existent response you received after submitting Telling Times to several publishers. The hybridity of the work counted against you, I’m sure. Can you tell us about the experience of self-publishing this work: the positives and negatives.

CMG: I have to be honest and acknowledge Susan’s energy and her skill which have brought us to this conclusion. We both have track records as readers and editors and do have genuine faith in each other’s work, and this gave us confidence that the book has something to offer. So I was only pleased to join a growing DIY Arts movement. Publishing independently is no longer tarnished by the vanity publishing label, for obvious reasons: the protocols of publishing work against us; a submission taking six months for a response or, regrettably, receiving none at all; and in the current underfunded climate, an experimental, mixed-genre text like ours is not going to be regarded as a commercial proposition. As well, many publishers insist that your work hasn’t been submitted elsewhere, so all this meant that we would simply run out of time to put our work out there. This is the subject of many conversations I have with poets who have long and substantial track records. And as some of them say about the current difficulties of getting published—just when we’d really learned the craft! The actual process of bringing this book to fruition has taught me a lot about the industry, and there is real satisfaction in taking creative responsibility for your work from first beginnings to having it in your hand. Perhaps the most positive part of the experience has been the fruitful collaboration between us, even about the nitty-gritty of publishing.

SM: While Carmel generously attributes the final production of this book to my energy and skill, I also have to say that she can be ridiculously modest about sending her work into the public domain. She would have left her exquisitely written novella languishing in a drawer if I hadn’t pushed her to send it to a publisher. But working on this project together has been a rewarding joint effort. We knew that finding a publisher would be difficult: neither poetry nor short stories are on top of publishers’ lists, and many publishers don’t accept either genre at all. So self-publishing it was. The positives of the process? Professional advice from Night Parrot Press enabled us to find a wonderful typesetter and printer, both of whom gave us choices typically unavailable from a publishing house. The typesetter gave us several options for the font and the layout, and he was perfectly happy for Carmel and me to keep making countless nitpicky changes with each draft, at no extra cost. The printer was also extremely accommodating about all stages of the process, while their in-house designer consulted with us about the cover, and gave us about 20 options! You rarely get that kind of flexibility with a traditional publisher. Self-publishing also allowed us to make changes at our own pace instead of having to adhere to a publisher’s deadline. Finally, we get to keep more of the proceeds from sales: a traditional publisher pays most writers a mere $2 per sale of a book! But there are of course negatives to the process, the two main ones being costs and marketing/distribution. The biggest costs were typesetting and printing, but there were also incidentals like postage and purchasing a bar code. We will now have to do all the marketing and distribution ourselves: it will be extremely time-consuming, and there’s no guarantee of a reward. As well, self-published works are ineligible for most literary awards. But despite all these obstacles, Carmel and I are delighted to be able to hold our book in our hands and to offer it to readers. We are proud of what we’ve created. Anyone interested in self-publishing is welcome to get in touch.

AC: And finally, and importantly, where can people buy the book? Will it be available also as an e-book? Audio-book?

CMG: We are selling it ourselves through readings and presentations. The Lane Bookshop in Claremont stocks copies of our book, and some libraries are accepting it. People can purchase a book by leaving a message on Susan’s website.

The book is also available on Amazon as a print-on-demand and as an e-book: check under the book’s title and the name of the authors. We know distribution is our next and biggest challenge, and we will take that on next year after the celebration of the launch winds down.

SM: Carmel and I will send a copy of the book to various independent bookshops, as well as preparing to brave face-to-face encounters with their managers. If readers enjoy the book, we would love them to use the power of word-of-mouth to promote it. Carmel and I would also welcome invitations from book clubs in Melbourne and Perth, respectively.

Telling Times was launched in Perth last month,

with a Melbourne launch to follow.