Defying Gravity: The Songwriting Dream I’m Finally Chasing in 2026

With the release of Wicked: For Good last weekend, my hubby, two at-home sons, and I rewatched Part 1 on Friday, then all but one of us (who opted to wait for streaming) went to the theatre to watch Part 2.

And with that, I’ve finally seen the whole show. A show I’ve claimed as one of my favourite musicals for nearly twenty years.

It did not disappoint.

I’ve already waxed at length about Wicked’s charms (including a comparison to Batman!), so I’ll let you read that post if you want more (with the one addition that these movies were some of the most beautiful I’ve ever seen—right up there with the 2002 film Hero). This post isn’t about that.

This post is about music. Specifically, how finally experiencing this story in its full glory affirmed a decision to take a leap toward a goal that has long seemed out of reach, pie-in-the-sky.

But, as Glinda the Good does when telling her and Elphaba’s story, I need to go back to the beginning.

Actually, I already did that too. But this time, I’m telling parts of the story I previously left out.

The Birth of a Dream

The Birth of a DreamFrom the time I was four years old, I was doing two things: reading books like my life depended on it, and making music.

Having been a music teacher for twenty years, I now know how rare it is that a four-year-old has the desire, discipline, and even the ability to read well enough to begin piano lessons at that age. While I did occasionally need some gentle encouragement to remember to practice, for the most part, I wanted to do it. And when my family had to give up my lessons when I was fourteen for financial reasons, I continued learning and advancing on my own.

Music was in my soul.

I was naturally talented as a musician—my mom told me I started singing before I started talking. But it still didn’t come “easy” to me, or so it felt.

When I was nine, my age-mate and second cousin Clay Hilman started taking lessons with my same teacher, and within a year, he was playing circles around me. (Clay is an incredibly talented and creative artist in multiple mediums to this day. I highly recommend you check out his albums—he has a wonderful Christmas one called “Little Blue Houses” that I can’t find online anywhere, unfortunately. But his other albums are also among my faves.)

At any rate, something about that experience implanted a deep doubt in my own ability as a musician.

When I later saw both the movie and stage play of Amadeus, the fictionalized story of how competing composer Antonio Salieri purportedly spent his life quietly manipulating Mozart to an early death due to professional jealousy, I deeply empathized with his feelings of inadequacy in the face of genius.

Not that I felt jealous of anyone. (Not even Clay—I got over that at around age eleven.) I just feared I was doomed to a life compelled to create beautiful and epic art only to be overshadowed by those more talented and capable than I.

“It’s not that I wanted fame and glory. I just wanted to make a living making music, and for my work to bless others the way the work of others had so often blessed and inspired me.”

I didn’t want fame and glory. I just wanted to make a living making music, and for my work to bless others the way the work of others had so often blessed and inspired me.

My voice, while passable and with good pitch, isn’t the stuff of pop legends (which was made clear to me by a well-meaning teacher in middle school—the truth often hurts, but I had a deep embarrassment about my singing voice in any context for years after that). But I’d started composing around the age of nine, and as soon as I heard there were people who made careers out of writing songs for other performers, I knew that was what I wanted to do.

So when I later made an almost last-minute decision to go to college, I chose a music diploma program, and the doors opened in miraculous ways for me to attend. Those two years were a turning point that changed the shape of my life and launched me down the path of being the career creative I am today.

More than a WishI knew, in my bones, that I’d been called to create music for a living.

So for the next fifteen years, around raising kids and moving all over the continent and working side-hustle businesses to help pay some bills and slowly fund my music career, I kept working.

I wrote songs—a lot of songs. My co-writer and college bestie and I finished the full-scale musical we’d begun in our second year. I forked out thousands of hard-earned dollars to get professional demos made of several of my best songs. I found a songplugger (the old-school way songwriters would get their songs to publishers and labels, like an agent for songwriters). I submitted to contests. I took songwriting courses and read craft books and kept growing my skills. I studied the music business and went to a music conference and made connections online. I paid for critiques of my songs. I slowly started buying the equipment and learning the skills I’d need to produce demos myself—or at least, half-decent scratch recordings.

And I saw some successes—two of my songs won awards. The songplugger seemed to think my music had potential. A couple of indie artists cut tracks of mine. Several indie record companies weren’t interested in the demo songs I’d sent them, but wanted to hear more demos (which I didn’t have). And when Candace and I presented a walk-through of our musical to some prominent contacts in Alberta’s theatre community, they also thought it had potential, if we kept working on it. (Circumstances shut that down at the time, and the project is currently in limbo.)

But during the fifteen years that all of this transpired, the music industry was undergoing a seismic shift. Streaming and YouTube took over, album sales dropped, and songpluggers were replaced by viral YouTube hits being noticed by producers. While I was excited by the potential of reaching people online, I was too busy with child-rearing and running our household on basically a single income barely supplemented by my part-time businesses (a choice my hubby and I made to prioritize our time together and with our children) to do much but study some of the musicians pioneering these new business models (such as YouTube a capella cover artist Peter Hollens and dancing violin sensation Lindsey Stirling).

But even though YouTube meant you could be a career musician without having to tour (something I never wanted), I still didn’t have the chops to be a singer-songwriter. I wanted to write for other artists.

“Despite all I’d done to move my craft forward, when it came to getting artists interested in my music, I had two obstacles: money and time. Mostly money.”

And, despite all I’d done to move my craft forward, when it came to getting artists interested in my music, I had two obstacles: money and time. Mostly money.

Remember how I said I’d had some pro demos made? Twenty-three years ago, “Walking in the Sonlight” and “The Nails (I Did This For You)” cost over a thousand dollars each. For songwriter’s demos—speculative projects to be tossed out into the void, not tracks for released that were expected to make money. (I did eventually release them, as demos, in the hopes of gaining more attention from industry folks—a spaghetti-on-the-wall experiment that didn’t pan out.)

Ten years later, “Let Me Love” set me back even more. And, by then, I’d discovered that no one really wanted to pay for music tracks anymore—not even $0.99. Napster (remember Napster?) and Spotify had trained audiences that they should expect music to be free or an all-you-can-download monthly subscription buffet.

A Dream InterruptedTo succeed in the music business, the common wisdom was to create demos of all your best songs (by 2012, I had at least two dozen in various genres I knew had potential—you do the production cost math) and pitch them over and over again.

To whom? Well, this was before Instagram, Facebook was barely past its startup you-and-your-high-school-friends phase, and YouTube was where scrappy indies pioneering new models covering popular songs or their own originals went, not professional artists looking to contract someone else’s music. (And I kind of missed the MySpace craze—I had an account, but never really got into it.)

To find the right industry people to pitch songs to, you needed to pay for an expensive directory or a subscription to one (which is somewhat still the case). Thank goodness you no longer needed to fork out postage to send demo CDs to these people, but that didn’t change the fact that someone truly wanting to gain traction in the music business needed to invest a lot of time and money (not either-or) to try to hit an ever-diminishing potential return on their investment, or be willing to start a YouTube business—though no one called it that at the time—as a performing musician.

So in 2015, when I published my first novella—a project that had taken me a couple of months and a few hundred dollars to produce basically on my own (with some hired freelancers for editing and cover design) without the hassle of depending on the career aspirations and schedules of others to “pick” me, and people were actually willing and eager to pay to read the finished result—I had to do some soul-searching.

After losing my son that year, I suddenly had space in my life (against my will, but there I was) to turn my attention back to my own career aspirations for the first time in over a decade. And, with much sorrow, I came to the conclusion that with the state of the music industry and my resources, it made more sense to pursue publishing than songwriting. It felt like hacking off part of my soul.

“After nearly two decades of actively pursuing my music career dreams, I’d been defeated not by my inadequacy as a songwriter but by the inadequacy of my resources in the face of an industry that had a high financial and time bar to entry.”

After nearly two decades of actively pursuing my music career dreams, I’d been defeated not by my inadequacy as a songwriter but by the inadequacy of my resources in the face of an industry that had a high financial and time bar to entry.

Ten years later, here I am, with a career as a novelist that is finally starting to see returns.

If I’d known it would take this much time and effort (and money, because this is an expensive industry, too) to get this far, would I have chosen to pursue publishing instead of just devoting that effort to a career as a musician?

Honestly, I don’t know. I don’t regret the choice I made, though. And, after returning to songwriting earlier this year, I realized I’m actually a far better songwriter now than when I stepped back ten years ago, thanks to my continued work in honing my storytelling and writing crafts.

So, as I so often say, “no skills gained are ever wasted.”

New Winds in my SailsThanks to AI, the music and publishing industries are both undergoing another seismic shift, along with every other creative (and non-creative) industry. And while that shift has some downsides, as these things always do, it’s also had a lot of upsides in lowering the bar to entry. (Actually, this is also contributing to the downside of an increased difficulty being visible in the noise, but that’s not a new problem.)

For me as a fiction writer, I don’t begrudge new writers using AI tools to finally realize their dreams. I know that AI used ethically isn’t a get-rich-quick scheme, but still a lot of work to learn the craft and business of publishing—and even for scammers using it unethically, I think of Proverbs 13:11: “Dishonest money dwindles away, but whoever gathers money little by little makes it grow.”

For me as a songwriter, AI has finally removed one of the biggest barriers to entry of creating music—the high cost of demo production.

After trying AI music tool Suno for the first time in April, I immediately got excited about music again, in a way I hadn’t anticipated. I hadn’t realized what a wound I still had in my soul about giving up on all the dreams I’d worked so hard for all those years, but creating music—both new songs and, for the first time, hearing some of my older songs with my ears the way I’d always heard them in my head—started to heal it.

A couple weeks ago, I wrote a song I knew had chart-topping potential, if it was performed by the right band. I’d written it for fun, on a bolt of inspiration from the most random source—a word mentioned on a tech podcast (moonshot) that became my hook.

And it made me stop and ask myself: What do I really want from my music?

To just make music for fun, forever, with AI-assisted productions that no one takes seriously and many automatically discount as “slop” without ever knowing how much craftsmanship and care and real humanity goes into each one—from writing and revising lyrics and melodies and chord structures, through production and post-production?

Or to do what I’d always wanted—to make money writing music?

As I typed that, my husband was listening to the final strains of “The Impossible Dream” performed by an epic pop diva in the other room, which is not his normal fare at all, and it feels like one more confirmation of what I decided last week:

I’m taking the leap and finally following my dream of professional songwriting.

“What do I really want from my music?The Not-So-Impossible Dream?

To just make music for fun, forever, with AI-assisted productions that no one takes seriously and many automatically discount as “slop” without ever knowing how much craftsmanship and care and real humanity goes into each one—from writing and revising lyrics and melodies and chord structures, through production and post-production? Or to do what I’d always wanted—to make money writing music?”

AI tools have empowered me to create demos of a production quality not even my pro demos previously achieved, and for only a few hours (well, quite a bit more than a few) of my time and a bit of money each. In fact, because of working with AI tools, I’m finally learning how to produce music well on my own. I’ve even been eying up some courses on music production. (I would love to learn to produce cinematic pop songs like Tommee Profitt.)

And some of the changes I missed in my decade away from the music industry have empowered freelance music professionals to take control of their own careers and make a living independent of music labels through online music service marketplaces.

That’s where I plan to start. To put out my shingle as a songwriter and lyric editor for hire. My goal is to be paid to write music by the end of 2026, even if it’s only one song, which seems perfectly achievable.

Am I giving up on publishing? Nope. I still have a lot of stories to tell, and I intend to keep telling them.

But when it comes to the dream that can bring me to tears I want it so bad? That’s songwriting.

And since I hope to inspire others to follow their dreams through the stories I tell, it’s high time I did that for myself.

It’s time to defy gravity and pursue my bone-deep calling.

Along with this shift in purpose, I’ve decided not to release any more of my demo tracks to streaming platforms, except for rare I-made-this-for-me-and-my-fans music. Instead, I’ll keep publishing them here on my website as part of my demo catalogue. However, any tracks I publish in my Listening Room blog will be public immediately. (No more “early access for premium Books and Tea League members” perk—they’ll still have plenty others.) Newsletter subscribers to my music content will be notified.

And if you’re a musician, or know one, who would be a good fit for any track I release, please let me know. (Watch for “Moonshot” to be put up as soon as I have time to finish production on it.)

I hope you’ll continue to come along with me on this journey.

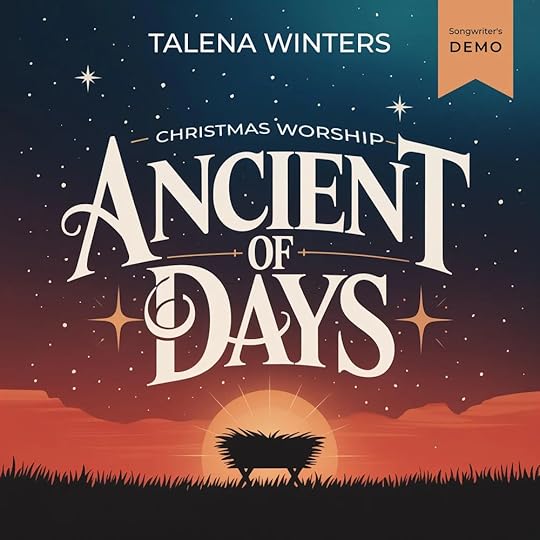

Latest Track: “Ancient of Days”

Earlier this week, I put up a Christmas song demo with two versions to enjoy. About the song:

Songwriter’s Demo: “Ancient of Days” is a Christmas worship song about the wonder of the all-powerful Creator choosing to come as a fragile, vulnerable infant. Driven by a Latin-inspired groove, the song works in both pop and rock styles. A show-stopper for Christmas services, concerts, or special features.

Listen Now