Our island nations and Mr Gove

I VERY NEARLY didn’t make it. The roads from Oakwood School, near Chichester, to just passed Guildford were fine, but then an all too typical Thursday late afternoon nightmare began to unfold on the A3 and stretched out all the way to Heathrow on the M25. I arrived at check-in 5 minutes after it had closed, my skin saved only, I reckon, by the look of total desperation on my face and my slightly askew bow tie.

Stepping off the plane and a wave of heat smacks me in the face. Within moments, sweat begins to drip down my back. Actually, I don’t mind it hot, but even by Japanese standards, so I am told, the current hot spell is off the scale. Today, I hear, temperatures are at similar record highs in the UK.

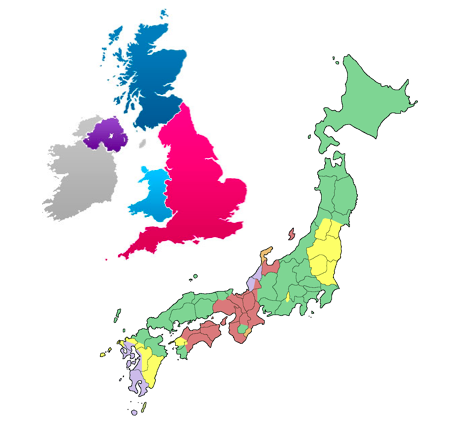

This is my second visit to Tokyo, within a year, and now I realise it is not just the current weather that seems to bind Britain and Japan. I am beginning to sense a kind of convergent evolution surrounding me as I sample, compare and contrast the culture, environment and plights of Japanese and British history.

Ostensibly there is little direct connection. Japan was never part of the British Empire . No Christians to speak of were successful in their quest for saving souls (there is even no word, I am told for ‘Bless you’ in Japanese). The language is as alien as if I had arrived on a mission to discover life on Mars. And geologically the fault lines that criss-cross the landscape – from the catastrophe of 3/11 to the predicted big one that is sometime set to rock Tokyo to its core – makes this a place with a destiny detached far off from the benign shores and shires of Blighty.

Yet, curiously, here I feel so much more at home that I have ever done when on a visit say to the US (now there’s an alien place).

How can this be?

I think I am beginning to see why.

Japan and the UK are both island nations. Our fortunes have traditionally rested on mastering the surrounding seas.A mutual fondness for feudalism has defined our cultures (samurai on the one hand, chivalrous on the other), sustained I suspect from prolonged periods of isolation from invasion. Manners and a certain reserve are hallmarks of our historic culture. Imperial ambitions unite our histories with empires mutually won, then lost. And today both of our nations still share an ongoing, profound and deep mistrust for our nearby continental neighbours (be they French / German or Chinese / Korean). We have a lot in common.

All of which makes me realise that a simple lack of historic contact is no excuse for ignoring the connections that we apparently share. I think the fact that we have far more in common than most people probably realise makes studying each other’s past just as important as studying our own. Only by looking outside and beyond ourselves can we hope to see our lot more objectively – the goal, surely, of any legitimate historical pursuit.

So Mr Gove – how about making the study of Japanese history part of your new compulsory history curriculum?

Alas, I don’t expect our views about the best way to study history converge much at all. On one level we seem to agree – I am all for learning history in context - and a chronological approach is one way to achieve that. But on another level we are as far apart as the miles currently separating me from my girls back home because I am quite sure that British history cannot and should not ever be considered as an ‘island story’ – separate and apart from the myriad interconnections and forces that have shaped our nation and culture over time.

Happily, universal condemnation of Gove’s initial proposals have taken out the most pernicious threads of his attempts to revive some monocultural national identity through a skewered teaching of history. But the thrust of history as a chain of British initiated events unleashed on ourselves and the rest of the world is still deeply woven in. When I plotted my top 10 moments from 1066 to the present day (which I presented last month at the Chalke Valley History Festival and which I list, as I promised I would, below) I found there were just as many to do with forces that shaped us as there were impacts we have had on others – human or non human.

That’s the problem with the whole idea of studying British history as a subject in itself. It begets an arrogance that’s myopic at best and chauvinist at worst. Any ‘Our Island Story’ rendition of history inevitably focuses on what we did to ourselves and our impact on the world, usually at the expense of the myriad forces that made us who we are. In an interconnected world such as we have today, mutual appreciation of the pushes and pulls of historical forces across all boundaries - national or disciplinary – is the absolute essence of it all.

So, as an antidote to Govanism, may I offer you this remarkable irony: thanks to a deep draught of what biologists term convergent evolution – our island story may probably come into sharper focus when viewed from a perspective here in Japan than ever it could back home.

Very best!

-chris

My current top 10 moments in ‘British History’ from 1066 to the present day (coat-of-many-pockets objects in parenthesis)

1) Invasion of England by Norman forces - aided by adoption of Chinese saddles / stirrups by European Medieval knights from Islamic fighters in France and Spain – (plastic stirrups)

2) Spread of Gunpowder to Europe via Islamic Spain - diffuses to England after Siege of Algeciras and used in anger for first time at the Battle of Crecy (toy gun)

3) Spread of Black Death originating in Henan Province China - leads to huge social / political change in Europe and England during 14th century (box of plasters)

4) Strategic decision by Henry VIII to plunder monasteries and build a fleet while at the same time the Chinese abandon naval power and build a wall (royal crown)

5) Statute of Monopolies, introduction of a system of patents by James 1st giving Britain pre-eminence in innovation and technology (royal seal)

6) Solving of the longitude problem by John Harrison in early 18th century - with his marine chronometer – gives British strategic navigational advantage at sea – helps build imperial power (compass)

7) Invention of high pressure steam power following successful trials of Richard Trevithick’s Puffing Devil, later harnessed by George Stephenson and his Rocket. This allows the British to exploit colonise overseas and import massive material wealth including saltpetre from India to sustain gunpowder supplies. Still today 75% of all electricity comes from steam power – (toy steam engine)

8) Rise of German power in first half of 20th century leads to eventual collapse of British Empire. Britain goes bankrupt by1974 (Postcard from Berlin)

9) Margaret Thatcher deregulates the City of London giving Britain a (probably temporary) new way of siphoning off wealth as North Sea Oil supplies dwindle (a domestic iron)

10) Instability of globalisation - Increasing inequality, overpopulation and a lack of seeing a more interconnected, holistic view of nature, science, history, economics and environment become the country’s biggest problems in common with most of the rest of the globe (witches cauldron)