Drawing, lithography, and experimentation

By Al R. Young

When I began experimenting with lithography in 1996, I focused on tonal rendering instead of line drawing because tonal pencil drawings had occupied much of my attention as an artist up until that time.

On the Borders of the North by Al R. Young,

On the Borders of the North by Al R. Young,

6 7/8 in. x 7 3/16 in., pencil on Bristol board, 1985This pencil drawing typifies the tonal rendering technique and architectural subject with which most of my artwork was concerned for many years.The work of artists whose interests draw them toward line as a means of expression has always delighted me, but my own interests invariably drew me toward tone instead. I came to realize that were I to pursue line, I would have to study idiom and technique before I could express the subject; indeed, before I could even discover my own artistic identity in terms of line and then complete the long and arduous journey toward mastery. I realized that, for me, I would have had to learn or perhaps even invent the vocabulary and syntax of a visual language and that--like all languages learned after the years of early childhood--it might never be a native tongue for me.

Eventually, I had to admit that I had no interest in pursuing such a course; that, instead of summarizing by means of line, wherein the nature of the subject is necessarily sorted--with a severe and demanding rigor--into starkly positive and starkly negative spaces, I wanted to pursue what, for me, constituted a fixed obsession with the vastness or infinity of tone. Of course, there is inherently as much infinity in line, I simply needed the feeling of wide open spaces that made tone my native air.

Columbine by Al R. Young,

Columbine by Al R. Young,

3 11/16 in. x 2 1/8 in. image, lithograph, 1997The editions of lithographs contain my first and only botanicals.When lithography became an option, I began drawing with a crayon as I had drawn in pencil. The changes, however, in terms of what I drew and the rate at which I did so were profound. The fluidity of lithography, as compared to pencil, significantly increased the rate at which drawings could be completed, but it was in terms of subject that the greatest change occurred.

Sharpening a wax pencil at the drawing table.The holder for the wax pencil is a pocket-sized holder for chalkboard-chalk. The wax-pencil-sharpener is built into the tool caddy clamped to the surface of the drawing table.Like a pencil, a crayon can be sharpened to a very fine point, but unlike a pencil, the point on a crayon lasts only a moment. This means that the control possible while drawing with a pencil is impossible while drawing with a crayon. Of course, pencils as well as graphite sticks and chunks can be grasped and wielded in many ways, but my approach to pencil drawing did not include such options because of the kind and quality of expression I sought. Lack of control in a medium can actually make an artist much more daring in a medium. (See

How do you look when you hold a pencil?

) Consequently, the range of subjects into which I ventured quickly expanded beyond anything I had attempted in pencil. In fact, grouped according to various kinds of experimentation, the portfolio of lithographic images represents a personal Lewis and Clark Expedition into the frontiers of subject matter possibilities:

Sharpening a wax pencil at the drawing table.The holder for the wax pencil is a pocket-sized holder for chalkboard-chalk. The wax-pencil-sharpener is built into the tool caddy clamped to the surface of the drawing table.Like a pencil, a crayon can be sharpened to a very fine point, but unlike a pencil, the point on a crayon lasts only a moment. This means that the control possible while drawing with a pencil is impossible while drawing with a crayon. Of course, pencils as well as graphite sticks and chunks can be grasped and wielded in many ways, but my approach to pencil drawing did not include such options because of the kind and quality of expression I sought. Lack of control in a medium can actually make an artist much more daring in a medium. (See

How do you look when you hold a pencil?

) Consequently, the range of subjects into which I ventured quickly expanded beyond anything I had attempted in pencil. In fact, grouped according to various kinds of experimentation, the portfolio of lithographic images represents a personal Lewis and Clark Expedition into the frontiers of subject matter possibilities:

Figures

Botanicals

Landscapes (sans architecture)

Interiors

Maritime

Black background

Nighttime lighting

Close-ups and vistas

Ornament and whimsy

Composition

Contrast

Gestalt

Occurring at an early period in the development of the Studios itself, our approach to the creation of these artworks also exerted a profound influence on these aspects of the work and operation of the Studios:

Models

Miniatures

Costuming

Props

Equipment

Photography

Archiving

Another important influence at the time was the invitation to illustrate a series of excerpts from The Country of the Pointed Firs by Sarah Orne Jewett. The invitation left up to us the decisions about kind and quantity of illustrations to be produced (the editorial staff making final decisions about what would be included with the installments). The only two stipulations were that Maine be the setting or subject for the artwork and that the illustrations be black and white--the latter requirement being rare in a print-world even then saturated with color.

During the lithographic period of my artwork, I thought I might actually continue making the kind of finely articulated, tonal pencil drawings to which I had devoted so many years, and I even ensured that enhancements to my drawing table could be as readily used for pencil work as for lithography, but the need never materialized. My interest in tone found expression in oil painting, a destination medium to which it had been traveling all along. And my work in lithography--having served a multiplicity of purposes at just the right time--appears to have had its day; even so, even that remains to be seen.

For some years now, my enduring enjoyment of the pencil as an artistic tool has found expression in the crafting of illustrations for The Papers of Seymore Wainscott, an ongoing creative project of the Studios that requires almost as much illustration as writing. And, much to my amazement and delight, drawings for the project, though hybrids, are not so much tonal as line . . .

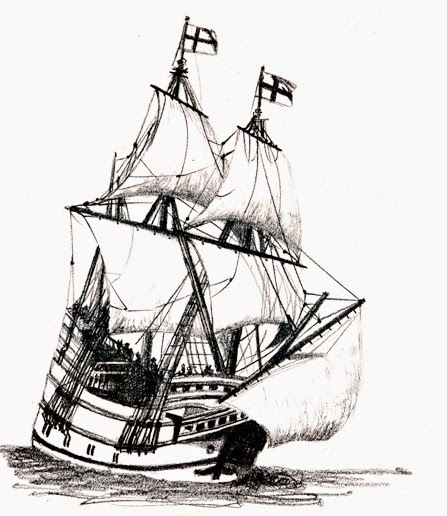

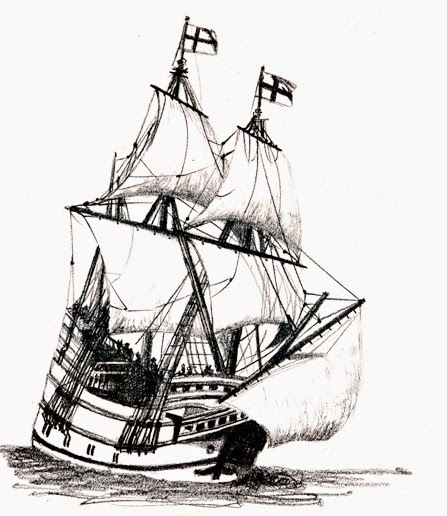

The Lyon by Al R. Young,

The Lyon by Al R. Young,

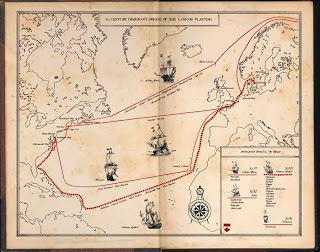

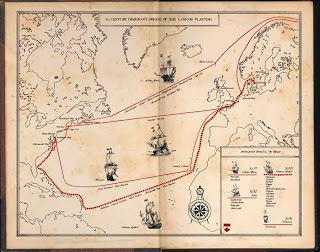

7 5/16 in. x 5 1/2 in., pencil sketch/computer enhancement, 2013This sketch was one of several hand-drawn images created as part of the complex, mixed-media illustration shown below. 17th Century Immigrant Origins of the Lanham Planting

17th Century Immigrant Origins of the Lanham Planting

by Al R. Young, mixed media, 2013This drawing is a component of one of 11 illustrations featured in Leornian Feldham Volume One , one of the novellas constituting The Papers of Seymore Wainscott.

When I began experimenting with lithography in 1996, I focused on tonal rendering instead of line drawing because tonal pencil drawings had occupied much of my attention as an artist up until that time.

On the Borders of the North by Al R. Young,

On the Borders of the North by Al R. Young,6 7/8 in. x 7 3/16 in., pencil on Bristol board, 1985This pencil drawing typifies the tonal rendering technique and architectural subject with which most of my artwork was concerned for many years.The work of artists whose interests draw them toward line as a means of expression has always delighted me, but my own interests invariably drew me toward tone instead. I came to realize that were I to pursue line, I would have to study idiom and technique before I could express the subject; indeed, before I could even discover my own artistic identity in terms of line and then complete the long and arduous journey toward mastery. I realized that, for me, I would have had to learn or perhaps even invent the vocabulary and syntax of a visual language and that--like all languages learned after the years of early childhood--it might never be a native tongue for me.

Eventually, I had to admit that I had no interest in pursuing such a course; that, instead of summarizing by means of line, wherein the nature of the subject is necessarily sorted--with a severe and demanding rigor--into starkly positive and starkly negative spaces, I wanted to pursue what, for me, constituted a fixed obsession with the vastness or infinity of tone. Of course, there is inherently as much infinity in line, I simply needed the feeling of wide open spaces that made tone my native air.

Columbine by Al R. Young,

Columbine by Al R. Young,3 11/16 in. x 2 1/8 in. image, lithograph, 1997The editions of lithographs contain my first and only botanicals.When lithography became an option, I began drawing with a crayon as I had drawn in pencil. The changes, however, in terms of what I drew and the rate at which I did so were profound. The fluidity of lithography, as compared to pencil, significantly increased the rate at which drawings could be completed, but it was in terms of subject that the greatest change occurred.

Sharpening a wax pencil at the drawing table.The holder for the wax pencil is a pocket-sized holder for chalkboard-chalk. The wax-pencil-sharpener is built into the tool caddy clamped to the surface of the drawing table.Like a pencil, a crayon can be sharpened to a very fine point, but unlike a pencil, the point on a crayon lasts only a moment. This means that the control possible while drawing with a pencil is impossible while drawing with a crayon. Of course, pencils as well as graphite sticks and chunks can be grasped and wielded in many ways, but my approach to pencil drawing did not include such options because of the kind and quality of expression I sought. Lack of control in a medium can actually make an artist much more daring in a medium. (See

How do you look when you hold a pencil?

) Consequently, the range of subjects into which I ventured quickly expanded beyond anything I had attempted in pencil. In fact, grouped according to various kinds of experimentation, the portfolio of lithographic images represents a personal Lewis and Clark Expedition into the frontiers of subject matter possibilities:

Sharpening a wax pencil at the drawing table.The holder for the wax pencil is a pocket-sized holder for chalkboard-chalk. The wax-pencil-sharpener is built into the tool caddy clamped to the surface of the drawing table.Like a pencil, a crayon can be sharpened to a very fine point, but unlike a pencil, the point on a crayon lasts only a moment. This means that the control possible while drawing with a pencil is impossible while drawing with a crayon. Of course, pencils as well as graphite sticks and chunks can be grasped and wielded in many ways, but my approach to pencil drawing did not include such options because of the kind and quality of expression I sought. Lack of control in a medium can actually make an artist much more daring in a medium. (See

How do you look when you hold a pencil?

) Consequently, the range of subjects into which I ventured quickly expanded beyond anything I had attempted in pencil. In fact, grouped according to various kinds of experimentation, the portfolio of lithographic images represents a personal Lewis and Clark Expedition into the frontiers of subject matter possibilities: Figures

Botanicals

Landscapes (sans architecture)

Interiors

Maritime

Black background

Nighttime lighting

Close-ups and vistas

Ornament and whimsy

Composition

Contrast

Gestalt

Occurring at an early period in the development of the Studios itself, our approach to the creation of these artworks also exerted a profound influence on these aspects of the work and operation of the Studios:

Models

Miniatures

Costuming

Props

Equipment

Photography

Archiving

Another important influence at the time was the invitation to illustrate a series of excerpts from The Country of the Pointed Firs by Sarah Orne Jewett. The invitation left up to us the decisions about kind and quantity of illustrations to be produced (the editorial staff making final decisions about what would be included with the installments). The only two stipulations were that Maine be the setting or subject for the artwork and that the illustrations be black and white--the latter requirement being rare in a print-world even then saturated with color.

During the lithographic period of my artwork, I thought I might actually continue making the kind of finely articulated, tonal pencil drawings to which I had devoted so many years, and I even ensured that enhancements to my drawing table could be as readily used for pencil work as for lithography, but the need never materialized. My interest in tone found expression in oil painting, a destination medium to which it had been traveling all along. And my work in lithography--having served a multiplicity of purposes at just the right time--appears to have had its day; even so, even that remains to be seen.

For some years now, my enduring enjoyment of the pencil as an artistic tool has found expression in the crafting of illustrations for The Papers of Seymore Wainscott, an ongoing creative project of the Studios that requires almost as much illustration as writing. And, much to my amazement and delight, drawings for the project, though hybrids, are not so much tonal as line . . .

The Lyon by Al R. Young,

The Lyon by Al R. Young,7 5/16 in. x 5 1/2 in., pencil sketch/computer enhancement, 2013This sketch was one of several hand-drawn images created as part of the complex, mixed-media illustration shown below.

17th Century Immigrant Origins of the Lanham Planting

17th Century Immigrant Origins of the Lanham Plantingby Al R. Young, mixed media, 2013This drawing is a component of one of 11 illustrations featured in Leornian Feldham Volume One , one of the novellas constituting The Papers of Seymore Wainscott.

Published on August 28, 2014 17:10

No comments have been added yet.