Furthest, Largest, Brightest...

We all love superlatives. In fact, 90% of the internet seems to be articles about the best, the biggest, the fastest and so on. So, not to be outdone, in this post I will be looking at some of the Universe’s superlatives. What’s the furthest, largest, brightest, hottest, coldest, fastest and loudest thing in the Universe?

What’s the furthest thing in the Universe?

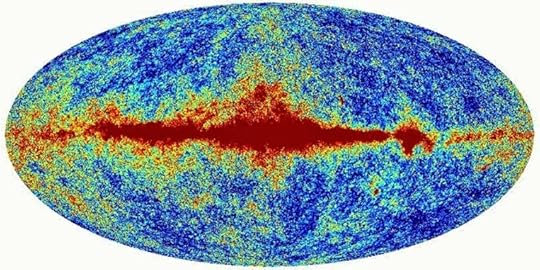

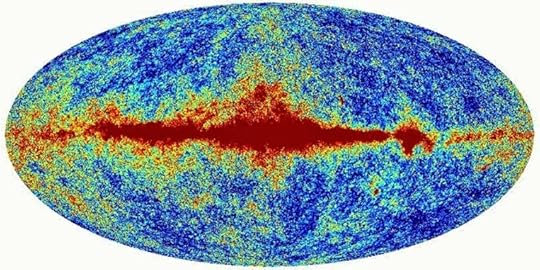

The CMB

The CMB

It is uncertain whether the Universe is finite or infinite in volume. Some very distant parts of the Universe may simply be too far away for light to have traveled to us on Earth since the Universe came into existence. This fact defines what astronomers call the ‘observable Universe’, that is, the parts of the Universe we can actually see. We can never discover anything about the Universe beyond this limit. There is no reason to suspect this limit is an actual ‘boundary’ to the Universe or that what lies beyond this has a ‘boundary’ at all. However, the edge of the ‘observable’ Universe lies about 46 billion light-years away in every direction. It is thus a sphere with a diameter of about 92 billion light-years and a volume of about 410 nonillion (410 thousand billion billion billion) cubic light-years!

However, the furthest ‘thing’ that the astronomer can actually detect in the Universe is the ‘Cosmic Microwave Background’ (or ‘CMB’), the background radiation left over from the Big Bang. The CMB is a snapshot of the oldest light in the Universe, imprinted on the sky when the Universe was just 380,000 years old as it first became transparent to light. The CMB, which is observed in the microwave region of the spectrum, shows tiny temperature fluctuations that correspond to regions of slightly different densities, representing the seeds of all future structure: the stars and galaxies of today.

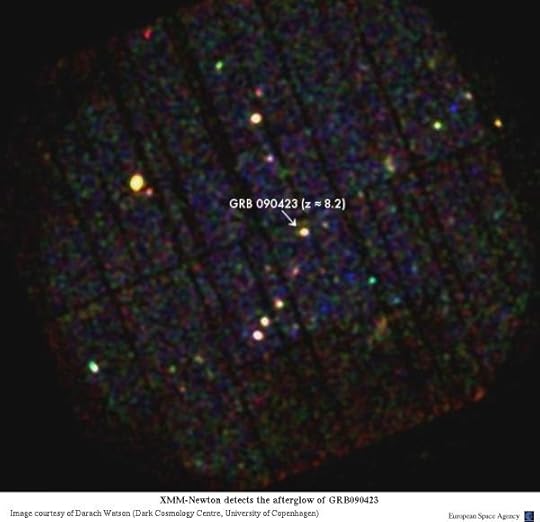

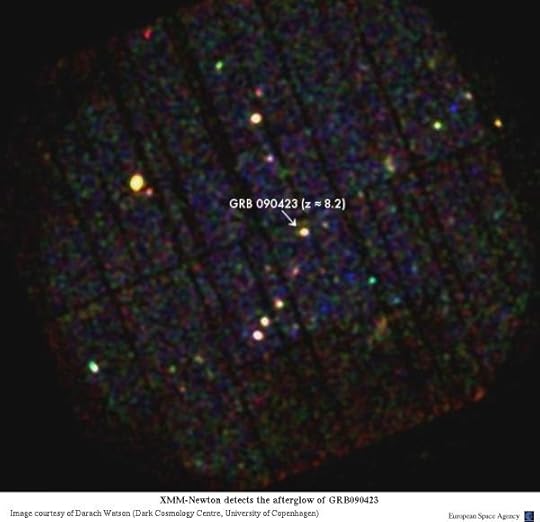

GRB 090423

GRB 090423

The furthest (and hence oldest) actual object known to man is a gamma-ray burst called GRB 090423. Gamma-ray bursts (GRBs) are extremely energetic flashes of radiation apparently caused by the collapse of massive stars to form neutron stars or black holes. They are the most energetic events in the Universe but are extremely rare. GRB 090423 was detected in April 2009 by NASA’s Swift satellite. With a redshift of 8.2, GRB 090423 emitted its light when the Universe was only 630 million years old and shows that even in the very early days of the Cosmos, massive stars were being born and then dying in catastrophic fashion.

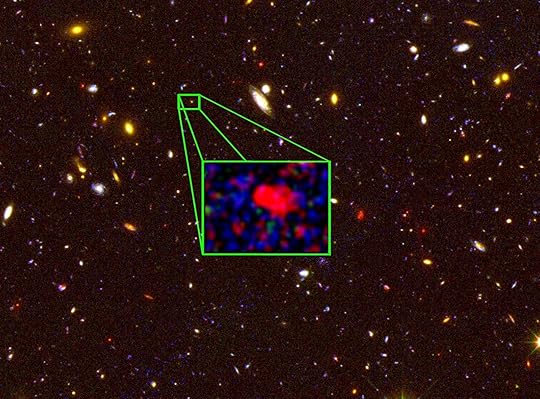

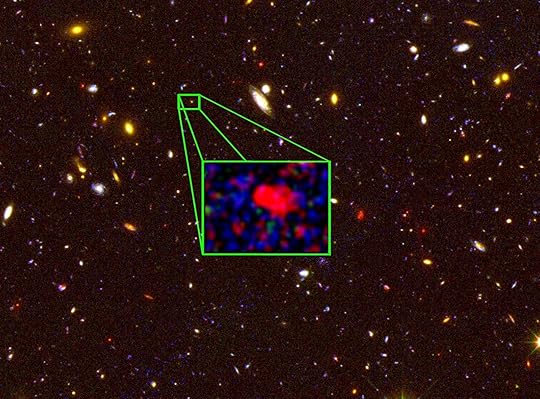

Currently, the most distant galaxy known to astronomers is called z8_GND_5296. It was discovered in 2013 using a combination of data from the Hubble Space Telescope and the W. M. Keck Observatory in Hawaii. With the highest redshift yet discovered (7.51), astronomers estimate its distance at 13.1 billion light years. This means we are seeing z8_GND_5296 as it was only 700 million years after the Big Bang. Since the Universe has expanded significantly in that time, z8_GND_5296 will now lie 30 billion light years from Earth. Not only is z8_GND_5296 a record holder, it is also an oddity. While normal galaxies like our own Milky Way may produce a couple of new stars each year, z8_GND_5296 has a star-formation rate 150 times greater. The observations of z8_GND_5296 have suggested that even more distant galaxies may be hidden in the fog of neutral hydrogen gas prevalent in the early Universe.

There are other objects that may be further away than GRB 090423 and z8_GND_5296. In fact, there is a list of more than 50 objects that may have higher redshifts. Unfortunately, due to difficulties in accurately measuring these dim objects, none of these have yet been confirmed.

z8_GND_5296

z8_GND_5296

What’s the largest thing in the Universe?

The largest known structure within the Universe is called the ‘Hercules-Corona Borealis Great Wall’, discovered in November 2013. This object is a galactic filament, a vast group of galaxies bound together by gravity, about 10 billion light-years away. This cluster of galaxies appears to be about 10 billion light-years across; more than double the previous record holder! In fact, this object is so big it’s a bit of an inconvenience for astronomers. Modern cosmology hinges on the principle that matter should appear to be distributed uniformly if viewed at a large enough scale. Astronomers can’t agree on exactly what that scale is but it is certainly much less than the size of the Hercules-Corona Borealis Great Wall. Its huge distance also implies this object was in existence only 4 billion years after the Big Bang. How such an immense object came into existence, and so quickly, challenges our current cosmological theories.

Astronomers cannot be absolutely sure which of the known stars are the biggest or most massive. The largest known star by radius is generally accepted as UY Scuti, a red hypergiant star about 9,500 light years from Earth. Its radius is probably 1,708 times the Sun’s (over a billion kilometres). The most massive star (rather than the largest) is probably RMC 136a1, a Wolf-Rayet star about 165,000 light years from Earth. It is believed the mass of RMC 136a1 is about 256 times the Sun’s mass.

What’s the brightest thing in the Universe?

The current record for the most energetic object yet discovered is another GRB. GRB 130427A, which, as its name indicates, occurred on 27 April 2013, was detected by many telescopes, on Earth and in space, and appears to have occurred in a small galaxy in the constellation of Leo, about 3.8 billion light years away. This is relatively nearby for a GRB which explains why it was so bright. In fact, GRB 130427A was more than five times brighter than the previous record holder. It was the biggest explosion astronomers know about, after the Big Bang itself. If it had occurred nearby, in our own arm of the Milky Way, it would have destroyed all life on Earth!

GRBs are rare and transitory events. The brightest steadily-emitting objects in the universe are quasars. These objects are the cores of distant galaxies in which a massive black hole feeds on a copious supply of stars and gas. As this doomed material spirals inwards it becomes white hot, and can shine with the light of more than thirty trillion Suns. The brightest known quasar, and also the most distant, is called ULAS J1120+0641. This quasar is powered by a black hole about two billion times more massive than our own Sun and was formed when the universe was just 770 million years old.

Some stars can burn brighter than quasars during the cataclysmic explosions that tear them apart known as ‘supernovae’. The brightest recorded supernova, equivalent to about 100 billion Suns, was called SN 2005ap, detected in a galaxy 4.7 billion light years away (called SDSS J130114+2743) in 2005. Since the brightness (or in fact ‘luminosity’) of a normal star generally increases with its mass, it is no surprise to find that RMC 136a1 is not only the most massive star known to man, but the brightest too.

What’s the hottest thing in the Universe?

Surprisingly, the hottest place in the Universe occurs right here on Earth. These humongous temperatures occur when sub-atomic particles are smashed together in the Large Hadron Collider. These temperatures, of the order of several trillion degrees are, however, insignificant compared to the temperature of the entire Universe just moments after the Big Bang. There, you can add as many zeros as you like to the temperature, only limited by the complete breakdown of physics during the first moments of creation.

Since GRBs are some of the brightest known events it isn’t surprising to find that they are also amongst the hottest. Temperatures generated in the cataclysmic interactions that create the fireball of relativistic particles in GRBs are likely to be in the region of a trillion degrees.

Other objects also produce very high temperatures. Neutrinos detected from a supernova that exploded in 1987 in the Large Magellanic Cloud (a nearby galactic neighbour to the Milky Way) showed that its core region reached a temperature of about 200 billion degrees. Normal stars can have surface temperatures up to about 50,000 degrees (blue supergiants). White dwarfs (the compact remnants of stars that have burnt out and contracted) have even higher surface temperatures. One white dwarf, called HD62166, measures a scorching 200,000 degrees and lights up a vast nebula with its painfully bright atmosphere. The interiors of stars are much hotter. The largest supergiant stars can have central temperatures up to about 6 billion degrees.

What’s the coldest thing in the Universe?

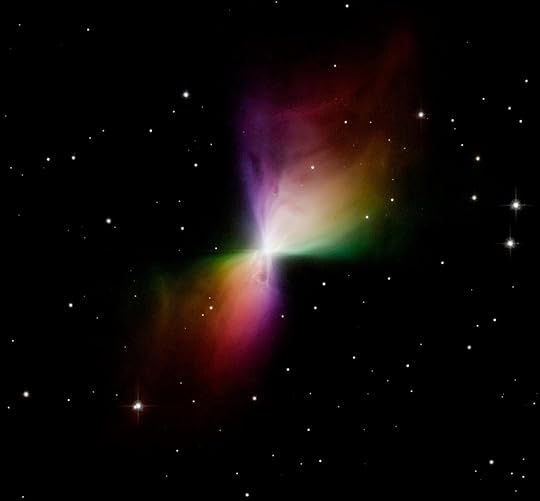

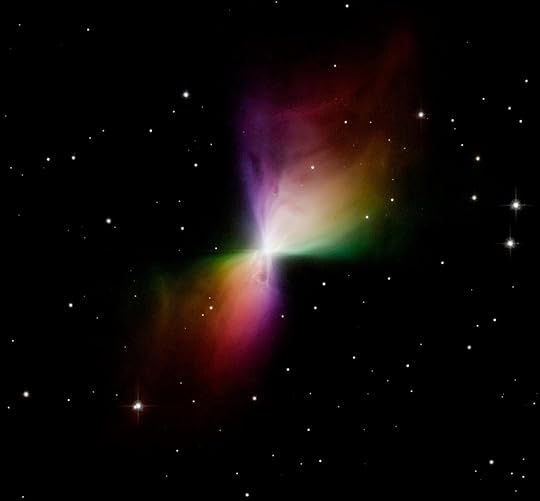

Physicists have determined that there is a lower limit to the temperature scale called ‘absolute zero’. It occurs at -273.15°C. No matter how much you cool something, it can never achieve absolute zero (though you can get pretty close). Strictly speaking, the coldest place in the Universe is also to be found on Earth. In a laboratory in Finland in 2000 a temperature only 100 trillionths of a degree above absolute zero was artificially created. However, the coldest naturally-occurring temperature in the Universe was discovered inside the Boomerang Nebula in 1995. This cloud of gas and dust, in the constellation of Centaurus, was thrown off by a star nearing the end of its life. Its temperature, a result of the slow expansion of the gas cloud, is only 1°C above absolute zero. Even the Big Bang’s relic radiation, the CMB, is warmer than the Boomerang Nebula at -270.42°C.

The Boomerang Nebula

The Boomerang Nebula

The coldest free-floating objects known to astronomers are ‘brown dwarfs’. But these are really ‘failed’ stars – they cannot be classed as planets but do not undergo hydrogen fusion which provides normal stars with their energy source. The latest research has shown that the coldest brown dwarfs have surface temperatures of between 125°C and 175°C. The boundary between these brown dwarfs and the coolest hydrogen burning stars (‘red dwarfs’) occurs at a mass of about 0.07 solar masses. Objects heavier than this are likely to be stars, those below will likely be brown dwarfs. However, this boundary is not well defined since other factors, such as the amount of heavy elements in the object, also determine whether or not hydrogen burning occurs. So, although red dwarfs are the coldest ‘real’ stars, with temperatures as low as 1800°C, brown dwarfs are the coldest ‘star-like’ bodies.

Space itself, being nothing, doesn’t have a temperature! However, astronomers often refer to the ‘temperature’ of a region of space to indicate the kinetic energy of matter in that region. Clouds of molecular hydrogen gas are generally cold at about -263°C, whilst some regions between galaxy clusters can reach temperatures of 10 million degrees. Generally, there isn’t enough matter in space to transfer this heat (or coldness) to other objects. So if you place an object in space the temperature it attains depends on how much radiation it receives and how good it is at absorbing and emitting that radiation. Put it near a star and it will generally heat up, for example. Its temperature, however, is just a measure of the heat balance between the object and its surroundings, and is not the temperature of ‘space’ itself.

What’s the fastest thing in the Universe?

Of course, the Universe has a self-imposed top speed limit - the speed of light at 299,792.458 km/s. Nothing moves faster than this. In fact, it’s not just light that travels at light speed. All mass-less particles do, as do the force fields such as the weak and strong nuclear forces and the gravitational force. So do ‘gravitational waves’, the ripples in the fabric of ‘space-time’ created by moving mass.

But let’s restrict ourselves to ordinary matter traveling at high speed. The record is held by ‘cosmic rays’. These aren’t ‘rays’ at all – they’re subatomic particles created in the most powerful events in the Universe such as galaxy mergers and ‘hypernovae’. The fastest cosmic ray yet detected was traveling so close to the speed of light that it had the same amount of energy as a medium-paced cricket ball, even though it was a fraction of the size of a single atom! It had a thousand billion billion times the energy of protons that the Large Hadron Collider can produce at maximum energy!

For large chunks of matter (as opposed to subatomic particles) the speed record is held by the ‘jets’ seen in ‘blazars’. Cannibalistic black holes at the heart of these active galaxies release huge amounts of energy which is funnelled into jets by a dense, highly-magnetic accretion disk. The jets in some blazars have been observed to move at about 99.9% the speed of light! These blobs of material are at least the size of the solar system!

What about the things we can see without the aid of a telescope, like stars? Well, to date, the fastest known star is an interesting Helium star called US 708. This star is one of a class of objects called hyper-velocity stars (or HSVs) which are characterised by being unbound to the Milky Way’s gravitational field, i.e. they move fast enough to one day leave our galaxy. Most HSVs are thought to be formed by the close encounters of stars with the Milky Way’s central black hole which sling shots them out of the galaxy. However, the trajectory of US 708 shows that this cannot be the case for this star. It is thought US 708 was formed in a binary star system as a companion white dwarf stripped material from US 708 as it became a red giant. The white dwarf then exploded as a supernova and ejected its companion at huge speed.

Stars also spin of course. At present, the fastest spinning star known to astronomers is called VFTS 102. This is a hot blue star, 25 times the mass of the Sun, residing within the Tarantula Nebula. At its surface, VFTS 102 is rotating at about 600 km/s (more than 1 million mph!) – so fast that it is almost, but not quite, flinging itself apart. The origins of this fast rotation are not yet clear, but it seems likely VFTS 102 was once part of a binary star system and was ‘spun up’ due to mass transfer from its now dead companion. Although VFTS 102 is the fastest rotating ‘normal’ star, ‘pulsars’ actually spin much quicker. Pulsars are the collapsed cores of stars that became supernovae. The fastest spinning pulsar yet discovered is known as Ter5AD. It rotates 716 times every second! That means the rotation speed at its equator is 70,000 km/s (about 158 million mph!), about 24% of the speed of light!

What’s the loudest thing in the Universe?

Sound is the movement of a pressure wave through matter. Since space is almost (but not quite) a complete vacuum, sound does not propagate easily through space. However, where matter is denser, such as in the atmospheres of planets, within stars, in gas clouds or in the environments surrounding black holes, sound waves are thought to be common. The ‘loudest’ sounds in the Universe are the ones carrying most energy.

Although there were no humans around to hear it, the Big Bang did in fact create sound. We can deduce the scale of these sound waves by observing the tiny temperature variations in the relic radiation from the Big Bang, the CMB. Their wavelength is measured in hundreds of thousands of light years, so the ‘notes’ are actually far too low to be heard by humans. The details are rather complicated but as a rough estimate we can calculate the loudness of these waves to be between 100dB and 120dB. Although this is near the human ear’s pain threshold (similar to standing next to a chainsaw or about 100m from a jet engine), it is by no means the loudest thing you could experience.

It is thought that the eruption of Krakatoa produced sound waves at about 180dB, whilst blue whales ‘talk’ at up to 188dB. It is estimated that the loudest thing on Earth was probably the explosion of the Tunguska Meteor (1908) at about 300dB. But somewhere in the Universe, perhaps where planets or black holes collide, or where supernovae explode, there may be sounds much more powerful than this.

What’s the furthest thing in the Universe?

The CMB

The CMBIt is uncertain whether the Universe is finite or infinite in volume. Some very distant parts of the Universe may simply be too far away for light to have traveled to us on Earth since the Universe came into existence. This fact defines what astronomers call the ‘observable Universe’, that is, the parts of the Universe we can actually see. We can never discover anything about the Universe beyond this limit. There is no reason to suspect this limit is an actual ‘boundary’ to the Universe or that what lies beyond this has a ‘boundary’ at all. However, the edge of the ‘observable’ Universe lies about 46 billion light-years away in every direction. It is thus a sphere with a diameter of about 92 billion light-years and a volume of about 410 nonillion (410 thousand billion billion billion) cubic light-years!

However, the furthest ‘thing’ that the astronomer can actually detect in the Universe is the ‘Cosmic Microwave Background’ (or ‘CMB’), the background radiation left over from the Big Bang. The CMB is a snapshot of the oldest light in the Universe, imprinted on the sky when the Universe was just 380,000 years old as it first became transparent to light. The CMB, which is observed in the microwave region of the spectrum, shows tiny temperature fluctuations that correspond to regions of slightly different densities, representing the seeds of all future structure: the stars and galaxies of today.

GRB 090423

GRB 090423The furthest (and hence oldest) actual object known to man is a gamma-ray burst called GRB 090423. Gamma-ray bursts (GRBs) are extremely energetic flashes of radiation apparently caused by the collapse of massive stars to form neutron stars or black holes. They are the most energetic events in the Universe but are extremely rare. GRB 090423 was detected in April 2009 by NASA’s Swift satellite. With a redshift of 8.2, GRB 090423 emitted its light when the Universe was only 630 million years old and shows that even in the very early days of the Cosmos, massive stars were being born and then dying in catastrophic fashion.

Currently, the most distant galaxy known to astronomers is called z8_GND_5296. It was discovered in 2013 using a combination of data from the Hubble Space Telescope and the W. M. Keck Observatory in Hawaii. With the highest redshift yet discovered (7.51), astronomers estimate its distance at 13.1 billion light years. This means we are seeing z8_GND_5296 as it was only 700 million years after the Big Bang. Since the Universe has expanded significantly in that time, z8_GND_5296 will now lie 30 billion light years from Earth. Not only is z8_GND_5296 a record holder, it is also an oddity. While normal galaxies like our own Milky Way may produce a couple of new stars each year, z8_GND_5296 has a star-formation rate 150 times greater. The observations of z8_GND_5296 have suggested that even more distant galaxies may be hidden in the fog of neutral hydrogen gas prevalent in the early Universe.

There are other objects that may be further away than GRB 090423 and z8_GND_5296. In fact, there is a list of more than 50 objects that may have higher redshifts. Unfortunately, due to difficulties in accurately measuring these dim objects, none of these have yet been confirmed.

z8_GND_5296

z8_GND_5296What’s the largest thing in the Universe?

The largest known structure within the Universe is called the ‘Hercules-Corona Borealis Great Wall’, discovered in November 2013. This object is a galactic filament, a vast group of galaxies bound together by gravity, about 10 billion light-years away. This cluster of galaxies appears to be about 10 billion light-years across; more than double the previous record holder! In fact, this object is so big it’s a bit of an inconvenience for astronomers. Modern cosmology hinges on the principle that matter should appear to be distributed uniformly if viewed at a large enough scale. Astronomers can’t agree on exactly what that scale is but it is certainly much less than the size of the Hercules-Corona Borealis Great Wall. Its huge distance also implies this object was in existence only 4 billion years after the Big Bang. How such an immense object came into existence, and so quickly, challenges our current cosmological theories.

Astronomers cannot be absolutely sure which of the known stars are the biggest or most massive. The largest known star by radius is generally accepted as UY Scuti, a red hypergiant star about 9,500 light years from Earth. Its radius is probably 1,708 times the Sun’s (over a billion kilometres). The most massive star (rather than the largest) is probably RMC 136a1, a Wolf-Rayet star about 165,000 light years from Earth. It is believed the mass of RMC 136a1 is about 256 times the Sun’s mass.

What’s the brightest thing in the Universe?

The current record for the most energetic object yet discovered is another GRB. GRB 130427A, which, as its name indicates, occurred on 27 April 2013, was detected by many telescopes, on Earth and in space, and appears to have occurred in a small galaxy in the constellation of Leo, about 3.8 billion light years away. This is relatively nearby for a GRB which explains why it was so bright. In fact, GRB 130427A was more than five times brighter than the previous record holder. It was the biggest explosion astronomers know about, after the Big Bang itself. If it had occurred nearby, in our own arm of the Milky Way, it would have destroyed all life on Earth!

GRBs are rare and transitory events. The brightest steadily-emitting objects in the universe are quasars. These objects are the cores of distant galaxies in which a massive black hole feeds on a copious supply of stars and gas. As this doomed material spirals inwards it becomes white hot, and can shine with the light of more than thirty trillion Suns. The brightest known quasar, and also the most distant, is called ULAS J1120+0641. This quasar is powered by a black hole about two billion times more massive than our own Sun and was formed when the universe was just 770 million years old.

Some stars can burn brighter than quasars during the cataclysmic explosions that tear them apart known as ‘supernovae’. The brightest recorded supernova, equivalent to about 100 billion Suns, was called SN 2005ap, detected in a galaxy 4.7 billion light years away (called SDSS J130114+2743) in 2005. Since the brightness (or in fact ‘luminosity’) of a normal star generally increases with its mass, it is no surprise to find that RMC 136a1 is not only the most massive star known to man, but the brightest too.

What’s the hottest thing in the Universe?

Surprisingly, the hottest place in the Universe occurs right here on Earth. These humongous temperatures occur when sub-atomic particles are smashed together in the Large Hadron Collider. These temperatures, of the order of several trillion degrees are, however, insignificant compared to the temperature of the entire Universe just moments after the Big Bang. There, you can add as many zeros as you like to the temperature, only limited by the complete breakdown of physics during the first moments of creation.

Since GRBs are some of the brightest known events it isn’t surprising to find that they are also amongst the hottest. Temperatures generated in the cataclysmic interactions that create the fireball of relativistic particles in GRBs are likely to be in the region of a trillion degrees.

Other objects also produce very high temperatures. Neutrinos detected from a supernova that exploded in 1987 in the Large Magellanic Cloud (a nearby galactic neighbour to the Milky Way) showed that its core region reached a temperature of about 200 billion degrees. Normal stars can have surface temperatures up to about 50,000 degrees (blue supergiants). White dwarfs (the compact remnants of stars that have burnt out and contracted) have even higher surface temperatures. One white dwarf, called HD62166, measures a scorching 200,000 degrees and lights up a vast nebula with its painfully bright atmosphere. The interiors of stars are much hotter. The largest supergiant stars can have central temperatures up to about 6 billion degrees.

What’s the coldest thing in the Universe?

Physicists have determined that there is a lower limit to the temperature scale called ‘absolute zero’. It occurs at -273.15°C. No matter how much you cool something, it can never achieve absolute zero (though you can get pretty close). Strictly speaking, the coldest place in the Universe is also to be found on Earth. In a laboratory in Finland in 2000 a temperature only 100 trillionths of a degree above absolute zero was artificially created. However, the coldest naturally-occurring temperature in the Universe was discovered inside the Boomerang Nebula in 1995. This cloud of gas and dust, in the constellation of Centaurus, was thrown off by a star nearing the end of its life. Its temperature, a result of the slow expansion of the gas cloud, is only 1°C above absolute zero. Even the Big Bang’s relic radiation, the CMB, is warmer than the Boomerang Nebula at -270.42°C.

The Boomerang Nebula

The Boomerang NebulaThe coldest free-floating objects known to astronomers are ‘brown dwarfs’. But these are really ‘failed’ stars – they cannot be classed as planets but do not undergo hydrogen fusion which provides normal stars with their energy source. The latest research has shown that the coldest brown dwarfs have surface temperatures of between 125°C and 175°C. The boundary between these brown dwarfs and the coolest hydrogen burning stars (‘red dwarfs’) occurs at a mass of about 0.07 solar masses. Objects heavier than this are likely to be stars, those below will likely be brown dwarfs. However, this boundary is not well defined since other factors, such as the amount of heavy elements in the object, also determine whether or not hydrogen burning occurs. So, although red dwarfs are the coldest ‘real’ stars, with temperatures as low as 1800°C, brown dwarfs are the coldest ‘star-like’ bodies.

Space itself, being nothing, doesn’t have a temperature! However, astronomers often refer to the ‘temperature’ of a region of space to indicate the kinetic energy of matter in that region. Clouds of molecular hydrogen gas are generally cold at about -263°C, whilst some regions between galaxy clusters can reach temperatures of 10 million degrees. Generally, there isn’t enough matter in space to transfer this heat (or coldness) to other objects. So if you place an object in space the temperature it attains depends on how much radiation it receives and how good it is at absorbing and emitting that radiation. Put it near a star and it will generally heat up, for example. Its temperature, however, is just a measure of the heat balance between the object and its surroundings, and is not the temperature of ‘space’ itself.

What’s the fastest thing in the Universe?

Of course, the Universe has a self-imposed top speed limit - the speed of light at 299,792.458 km/s. Nothing moves faster than this. In fact, it’s not just light that travels at light speed. All mass-less particles do, as do the force fields such as the weak and strong nuclear forces and the gravitational force. So do ‘gravitational waves’, the ripples in the fabric of ‘space-time’ created by moving mass.

But let’s restrict ourselves to ordinary matter traveling at high speed. The record is held by ‘cosmic rays’. These aren’t ‘rays’ at all – they’re subatomic particles created in the most powerful events in the Universe such as galaxy mergers and ‘hypernovae’. The fastest cosmic ray yet detected was traveling so close to the speed of light that it had the same amount of energy as a medium-paced cricket ball, even though it was a fraction of the size of a single atom! It had a thousand billion billion times the energy of protons that the Large Hadron Collider can produce at maximum energy!

For large chunks of matter (as opposed to subatomic particles) the speed record is held by the ‘jets’ seen in ‘blazars’. Cannibalistic black holes at the heart of these active galaxies release huge amounts of energy which is funnelled into jets by a dense, highly-magnetic accretion disk. The jets in some blazars have been observed to move at about 99.9% the speed of light! These blobs of material are at least the size of the solar system!

What about the things we can see without the aid of a telescope, like stars? Well, to date, the fastest known star is an interesting Helium star called US 708. This star is one of a class of objects called hyper-velocity stars (or HSVs) which are characterised by being unbound to the Milky Way’s gravitational field, i.e. they move fast enough to one day leave our galaxy. Most HSVs are thought to be formed by the close encounters of stars with the Milky Way’s central black hole which sling shots them out of the galaxy. However, the trajectory of US 708 shows that this cannot be the case for this star. It is thought US 708 was formed in a binary star system as a companion white dwarf stripped material from US 708 as it became a red giant. The white dwarf then exploded as a supernova and ejected its companion at huge speed.

Stars also spin of course. At present, the fastest spinning star known to astronomers is called VFTS 102. This is a hot blue star, 25 times the mass of the Sun, residing within the Tarantula Nebula. At its surface, VFTS 102 is rotating at about 600 km/s (more than 1 million mph!) – so fast that it is almost, but not quite, flinging itself apart. The origins of this fast rotation are not yet clear, but it seems likely VFTS 102 was once part of a binary star system and was ‘spun up’ due to mass transfer from its now dead companion. Although VFTS 102 is the fastest rotating ‘normal’ star, ‘pulsars’ actually spin much quicker. Pulsars are the collapsed cores of stars that became supernovae. The fastest spinning pulsar yet discovered is known as Ter5AD. It rotates 716 times every second! That means the rotation speed at its equator is 70,000 km/s (about 158 million mph!), about 24% of the speed of light!

What’s the loudest thing in the Universe?

Sound is the movement of a pressure wave through matter. Since space is almost (but not quite) a complete vacuum, sound does not propagate easily through space. However, where matter is denser, such as in the atmospheres of planets, within stars, in gas clouds or in the environments surrounding black holes, sound waves are thought to be common. The ‘loudest’ sounds in the Universe are the ones carrying most energy.

Although there were no humans around to hear it, the Big Bang did in fact create sound. We can deduce the scale of these sound waves by observing the tiny temperature variations in the relic radiation from the Big Bang, the CMB. Their wavelength is measured in hundreds of thousands of light years, so the ‘notes’ are actually far too low to be heard by humans. The details are rather complicated but as a rough estimate we can calculate the loudness of these waves to be between 100dB and 120dB. Although this is near the human ear’s pain threshold (similar to standing next to a chainsaw or about 100m from a jet engine), it is by no means the loudest thing you could experience.

It is thought that the eruption of Krakatoa produced sound waves at about 180dB, whilst blue whales ‘talk’ at up to 188dB. It is estimated that the loudest thing on Earth was probably the explosion of the Tunguska Meteor (1908) at about 300dB. But somewhere in the Universe, perhaps where planets or black holes collide, or where supernovae explode, there may be sounds much more powerful than this.

Published on April 10, 2015 07:59

No comments have been added yet.