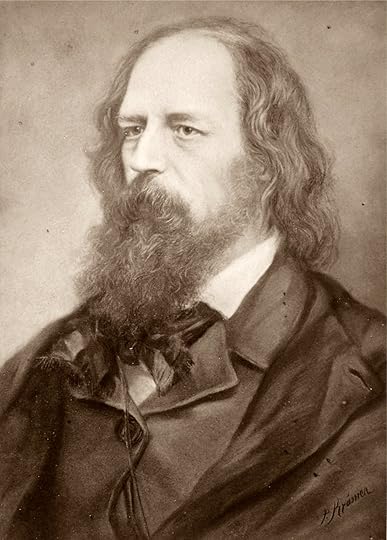

”Tennyson knew his magician’s business.”

- Aldous Huxley

Reputation – 4/5

Tennyson’s age is long past. It ended almost as soon as he died. We now think of him (if we think of him at all) as the preeminent poet of the Victorian era, during which time he was England’s Poet Laureate for 42 years. He took the title over from Wordsworth in 1850 and held it until his death in 1892.

His poetry sold by the thousands while he was alive, and for another 20 years after. But after about 1920, people stopped reading him. A testament to his shift in popularity can be confirmed by an eBay search for vintage editions of his works. There are countless Tennyson printings from the late 19th Century that now sell for less than $50. It’s harder to find Tennyson collections from the 1920s because no one was printing them.

Like Dryden and Pope, Tennyson’s reputation suffers from a shift in cultural values. The Victorian era was long when considered as the lifetime of one monarch, but short when considered as a cultural movement. That old world was shattered forever by 1918, and Tennyson’s verse is now just another casualty tossed in the grave with the Crystal Palace and Utilitarianism.

Point – 5/5

As a boy, Alfred, Lord Tennyson never thought of being anything other than a poet, and his early dedication to his craft stood him in good stead. He read and wrote poetry insatiably and he absorbed everything he studied. He could imitate anyone from Spenser to Shelley. How clear is the concentration of Keats’ style in this oft-cited stanza:

”So waste not thou, but come; for all the vales

Await thee; azure pillars of the hearth

Arise to thee; the children call, and I

Thy shepherd pipe, and sweet is every sound,

Sweeter thy voice, but every sound is sweet;

Myriads of rivulets hurrying thro’ the lawn,

The moan of doves in immemorial elms,

And murmuring of innumerable bees.”

A textbook example of assonance.

Tennyson had a wonderful ear for lyric and rhythm, but he did not rely on it too heavily. Very little of his poetry is ethereal or abstract. When he writes a pastoral in the style of Wordsworth, he is less wordy, more worthy. When he writes a ballad, it takes the traditional form a short story in verse with the rhythm of a song. The Lady of Shallot sets the standard for the neo-medieval ballad. It had an enormous effect on Tennyson’s contemporaries and still holds up today.

Tennyson is a prime example of a master craftsman who can handle all the traditional forms and techniques with ease.

But he was also an originator. And his most famous innovation was the dramatic monologue – a character speech addressing either the reader or an implied audience. It is a form derived from the blank verse soliloquies found in the plays of Shakespeare and Marlowe. Some of the most famous lines in English are lifted from these speeches. Mark Anthony’s “Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears,” and Tamburlaine’s “And shall I die, and this unconquered?” are the ancestors of the form Tennyson developed.

Ulysses is Tennyson’s most perfect achievement in the dramatic monologue. In it we hear the hero of Homer’s Odyssey as an old man reflecting on his past life of war and travel and wondering if it is really his fate to fade away in old age. Or… can he gather his men for one last adventure?

”There lies the port; the vessel puffs her sail;

There gloom the dark, broad seas. My mariners,

Souls that have toil’d, and wrought, and thought with me,—

That ever with a frolic welcome took

The thunder and the sunshine, and opposed

Free hearts, free foreheads,—you and I are old;

Old age hath yet his honor and his toil.

Death closes all; but something ere the end,

Some work of noble note, may yet be done,

Not unbecoming men that strove with Gods.

The lights begin to twinkle from the rocks;

The long day wanes; the slow moon climbs; the deep

Moans round with many voices. Come, my friends.

’T is not too late to seek a newer world.”

It is one of those few poems that are positively thrilling. Thrilling in the same way as a speech in Macbeth or King Lear. It is no exaggeration to say that its drama is on par with Shakespeare. Only it is just one scene.

The longest poem in this collection is a blank verse story about a man named Enoch Arden. It was immensely popular in Victorian times, and is, almost surprisingly, still good today.

Another old-time favorite is Locksley Hall, a medium-length poem following the mind of a young man who is rejected, forlorn, and then resolved. But its 19th Century morality is painfully clear, and I doubt a common type of goodreads user will be able to keep from calling it racist and sexist and rating the whole book one star in retaliation.

And here we return to the problem of Tennyson today. His morals and subject matter are outdated to us – synonymous with the Victorian era – and his poetic technique – though uniquely combined in Tennyson – we find scattered in other poets of wider appeal like Keats, Wordsworth, and Shakespeare.

I don’t think it’s an overstatement to say that Tennyson is the most widely skilled poet in English. He can do Byron and Shelley nicely, Keats very well, and Wordsworth oftentimes more tolerably than Wordsworth, himself. He can even do some Shakespeare.

If Tennyson had been born in an age with greater poetic force, he would easily have been one of the greatest English poets. Even just 30 years earlier he might have towered over the other Romantics as a summation of all their powers. But as it is he ends up in a sort of no man’s land of English poetry. The time in which he lived makes him into a poet of a specific period, and he is denied the universality that his artistry merits. It’s a fate that other first rank poets like Pope have also suffered, and one that I think ought to be rectified.

In light of the whole of English poetry from Chaucer onwards, Tennyson can be considered the last truly great figure. He offers a logical end to the English tradition by combining conventional forms with his own innovations, all with an exceptional poetic sensibility and a keen eye on the past. And appropriately, there is something elegiac about all of Tennyson’s poetry. Even when he is robust and energetic, there is always a stately solemnity to him. It’s as if he knows he’s delivering a eulogy for not merely his age, but for the whole tradition, and he does so with the dignity and eloquence that we have come to expect from a Victorian gentleman.

Recommendation – 4/5

There are two things that I think Tennyson does better than any other poet. The first is his uniquely English stoicism. The Victorians were known for their “stiff upper lip” and Tennyson expresses that sort of reserved manliness in verse. Even his elegy for his best friend, In Memoriam A.H.H (not included in this selection), is not the least bit weepy. It’s overarching sentiment is expressed in the immortal lines:

”I hold it true, whate'er befall;

I feel it when I sorrow most;

'Tis better to have loved and lost

Than never to have loved at all.”

They are lines that could have been written by Seneca. Another flawless example of Victorian stoicism comes in the form of The Charge of the Light Brigade, a tribute to the cavalry regiment in the Crimean War that was torn to pieces obeying unwise orders.

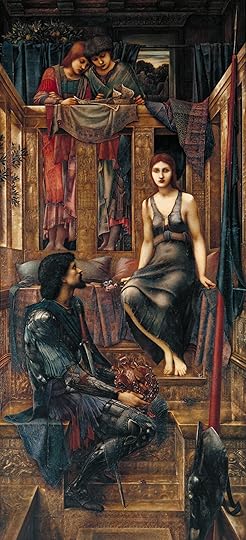

The second field in which Tennyson is unmatched is his medievalism. Before Tolkien, there was no writer who could evoke the Middle Ages so well. Tennyson’s most medieval work, The Idylls of the King is too long for this short selection, but there are other pieces like The Lady of Shallot and Merlin and the Gleam that are sure to please fans of King Arthur.

Personal – 4/5

I don’t care for medievalism at all, but Tennyson is so good at it that even I don’t mind his fascination with that realm of escapism. His stoicism always keeps him from becoming too much like a fairy tale.

In my view, Tennyson fits perfectly into that succession of exceedingly “English” poets. I have in mind those poets whose very “Englishness” makes them perennial favorites in their own country, but relatively ignored outside it. Spenser, Milton, Dryden, and Wordsworth are the great poets I have in mind.

Not being English, I lean towards that tradition of poets whose work is more beloved abroad. Chaucer, Pope, Byron, and Browning are a few of the great English poets whose work has always been more popular outside of England and in translation.

But despite Tennyson’s sometimes overwhelming Englishness, his mastery and masculinity win me over. That’s not to say he cannot be tender. One of his short lyric poems (unfortunately not included in this selection) is a meditation on trust in a relationship. Vivien’s Song is the admonition of a profound and honest woman, and expresses the poison of distrust in metaphors that are unforgettable:

”’In Love, if Love be Love, if Love be ours,

Faith and unfaith can ne’er be equal powers:

Unfaith in aught is want of faith in all.

‘It is the little rift within the lute,

That by and by will make the music mute,

And ever widening slowly silence all.

‘The little rift within the lover’s lute

Or little pitted speck in garnered fruit,

That rotting inward slowly moulders all.

‘It is not worth the keeping: let it go:

But shall it? answer, darling, answer, no.

And trust me not at all or all in all.’”