What do you think?

Rate this book

144 pages, Hardcover

First published February 12, 2001

JJ Thomson, of fat man and violinist fame, is intentionally less entertaining here than she was in her early works. She even spends a fair bit of time pondering the question of whether one ought to ring a doorbell, a scenario selected for being maximally quotidian. So, it falls to me to make up for the lack of shitposting in the book with shitposting in this review.

Thomson's main theses are that monistic axiology is false, hedonistic axiology is false, and consequentialism is therefore false and cannot have any advice to offer. (Plus a positive project of developing a rights-based normative theory, starting from the arguments used in the negative project.)

Let's start with hedonism, which is discussed early in the book, and subsequently ignored. Thomson's single argument against hedonism is that delighting in the suffering of others is necessarily wrong, and hedonism would have us believe otherwise. She's right about the second part, but what reason do we have to think schadenfreude is a moral bad? ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ Thomson simply takes it as given. No hedonist should find this at all persuasive. If we investigate the reasoning underlying the admittedly (pre-theoretically) compelling intuition, we should expect to find that it bottoms out either in concerns about downstream negative outcomes (i.e., incentivization to cause more suffering, and more suffering is bad), which are concerns that hedonic utilitarianism shares, or in no clear reason at all, in which case, the intuition is highly suspect. In any case, there appears to be no reason not to cheerfully bite the bullet and maintain that delight in the suffering of others, considered in isolation, is a moral good.

But what do people other than myself think of all this? In a methodologically unsound effort to do a bit of X-phi, the results of which should not be taken as strong evidence or representative of any population, I posted the following in a meme group accustomed to hosting some serious philosophical discussion:

There's nothing you can do to prevent the victims from getting run over, and you are inevitably going to witness their deaths. You might avert your eyes, but their screams will still reach your ears.

You do, however, have a bottle of the fast-acting wonder drug Desadiol™, one dose of which will cause you to take pleasure in the suffering of others for just a couple minutes, overriding the horrified and potentially traumatic reaction you'd normally have. It's been conclusively demonstrated that Desadiol™ has no lasting effects (although this doesn't rule out the possibility of your experiences while under the influence having a lasting effect). There's no one else nearby. Should you take the Desadiol™?

Reactions were quite strong and split down the middle: half the people commenting were in agreement with Thomson; half were (without prompting beyond what I quoted above) in agreement with me. This does at least suggest that the view I have defended here is not rare. Toward the end of Goodness & Advice, Thomson claims that when confronted with such earnestly held and not anomalous intuitions that are contrary to the normative framework one is defending, one ought at least to address them and give some reason for favoring the theory over the intuition. As such, Thomson's assumption that the intuition on which her argument rests should go uncontested looks to be a failure by her own standards.

So much for the argument against hedonism. What about monism? Thomson rests her argument against it on observations about how the word 'good' is used in ordinary language. So, for example, when we say "that's a good knife", we are not commenting on the same qualities that we are commenting on in saying "that's a good pen". This is, frankly, a bizarre argument. How do we get from these observations to claims about an objectively correct normative theory? ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ Again, Thomson doesn't clearly explain this.

In observing a mustachioed villain tying five victims to a trolley track, none of whom succeed in their struggles to break free, I might say, "That's some good rope", for tensile strength is a sign of good rope. Having watched the trolley run the hapless victims over without slowing, I might say, "That's a good, well-engineered trolley", for it behooves a trolley to be able to plow through such obstructions, not allowing them to interfere with regularly scheduled service. Later, I might learn that this villain is a repeat offender who's been evading the cops for months, and exclaim, "Wow, that guy's really good at what he does!"

What implications does all this have for normative theorizing? Absolutely none. Clearly, it's not good in a moral sense that the rope was put to such use, or that the trolley didn't stop, or that the villain keeps tying people to trolley tracks.

The way we ordinarily use the word 'good' is a contingent feature of the language we in fact speak. It's dubious to use it in support of a particular flavor of moral realism. To the extent that it is indicative of objective truths, the point is surely teleological. And teleology ain't axiology. Thomson doesn't get that. There is, contrary to her claims in this book, no compelling argument to be found in these observations against consequentialism and the view that the only moral good is valence of subjective experiences.

And what of the commentary? It doesn't address the the points I've made here (Schneewind makes some points that seem adjacent to mine about the contingent nature of language, but they're not close enough, and neither is Thomson's reply). The commentators are generally content to let Thomson's strongest claims go unchallenged, choosing instead to argue some finer points. Nussbaum, at least, raises the issue of pluralist consequentialism - specifically, the views advanced by Amartya Sen - and that leads to some interesting discussion. Not that there isn't any interesting discussion elsewhere in the book, but as I have argued here, it largely flows from faulty premises, and as such, is ultimately rather unenlightening. The positive project, which gets less attention and which I haven't discussed here, is of some interest, but less spicy and surprising than the negative project, and with the negative project so unpersuasive, we're left with no strong reason to accept it either.

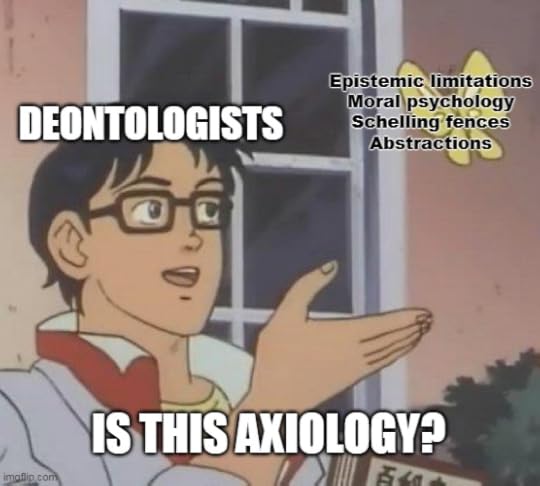

In conclusion, I should have included polysemy when I made this meme: