What do you think?

Rate this book

176 pages, Paperback

First published March 1, 1985

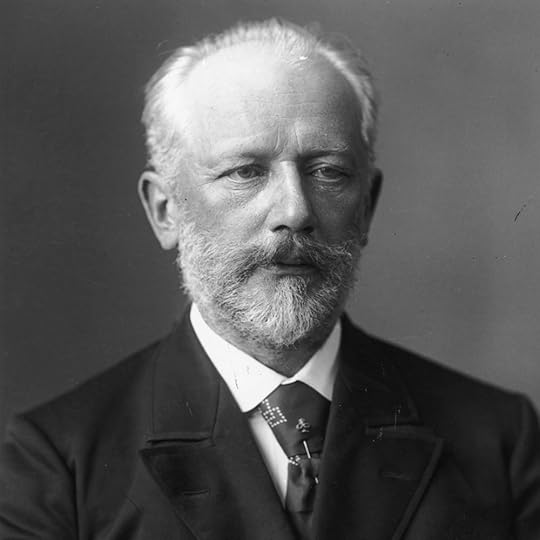

“Now, on my journey, the idea of a new symphony came to me, this time one with a programme, but a programme that will be a riddle to everyone. Let them try and solve it... The programme of this symphony is completely saturated with myself and quite often during my journey I cried profusely.”

“Simon Karlinsky, a composer and professor of Slavic languages and literature at UC Berkeley and “an expert on homosexuality in pre-Soviet culture”, wrote in the gay literary magazine Christopher Street in 1988 that in 1941 a musician friend of his youth called Alex, who had spent several months associating with the painter Pavel Tchelitchew, told him an oral tradition that Tchelitchew had heard from the composer's brother Modest, told to him by Tchaikovsky himself. According to this, what Karlinsky himself calls “poorly remembered hearsay”, the secret programme of the symphony is about love between men: the search for it, from the beginning of the first movement; finding it, in the romantic andante theme (measure 89); and the attacks of a hostile world on it, in the agitated allegro vivo passage that follows (measure 161); and escape from that, in the return to the love theme (andante come prima, measure 305). The last movement, Karlinsky was told, is an elegy for a dead lover.”

None but the lonely heart

Can know my sadness.

Alone and parted

Far from joy and gladness,

Heaven's boundless arch I see

Spread about above me.

O what a distance dear to one

Who loves me.

None but the lonely heart

Can know my sadness.

Alone and parted

Far from joy and gladness,

My senses fail,

A burning fire

Devours me.

None but the lonely heart

Can know my sadness.

— Goethe