What do you think?

Rate this book

66 pages, Paperback

First published October 28, 2006

— Like water, he says to George. Yes. Like water.

— I don't know how long I remained, bent over the page, he says. But it was a long time. A long time. I wondered if I would be able to hold out. If my fingers would be able to stand it. But of course they did. I did. Till it was done.

— I stopped, he says. I closed my eyes. I was exhausted. As if I had finally done what I had been put in the world to do.

— I bent my shoulders, he says to George, who nods and strokes his moustache. I bent my shoulders and let my arms hang down. I stayed like that for a long time. A long long time. And then I opened my eyes and began to look over what I had written.

— The page was black, he says. It was black with marks. Thick with them. Nothing was legible. And the page underneath was white. With the traces of writing where I had pressed on the page above. And the traces gradually disappeared as I turned one page after the other, until there was nothing but whiteness. Pure whiteness. Page after page.

— I hadn't turned the page, he says. Not once. All the time I was writing. I hadn't turned the page.

[53]

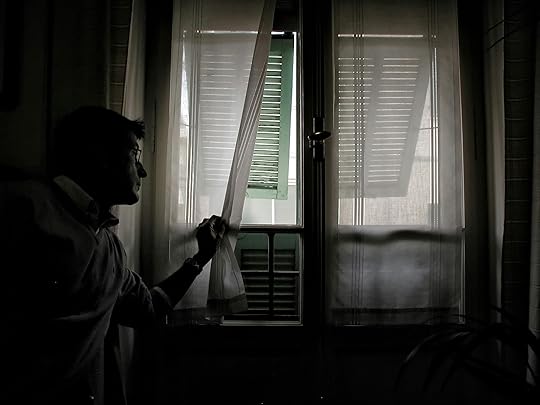

— I could see myself in the empty room, he says to George, who nods and strokes his moustache. I could see myself at the window.

— Sometimes, he says to George, my feet echoed on the bare boards. Sometimes there was only silence. Greyness and silence. Inside the room and out. Greyness and silence.

— Sometimes, he says, I could hear the cries of children in the playground below, and sometimes I could hear the distant hum of city traffic. But most of the time there was just greyness and silence, greyness and silence, and my face at the window, looking out.

[57]