What do you think?

Rate this book

About the Author: Saira Shah lives in London and is a freelance journalist. She was born in Britain of an Afghan family, the daughter of Idries Shah, a writer of Sufi fables. She first visited Afghanistan at age twenty-one and worked there for three years as a freelance journalist, covering the guerilla war against the Soviet occupiers. Later, working for Britain's Channel 4 News, she covered some of the world's most troubled spots, including Algeria, Kosovo, and Kinshasa, as well as Baghdad and other parts of the Middle East. Her documentary Beneath the Veil was broadcast on CNN.

253 pages, Paperback

First published January 28, 2003

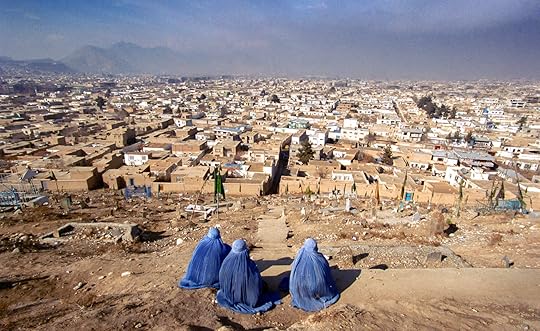

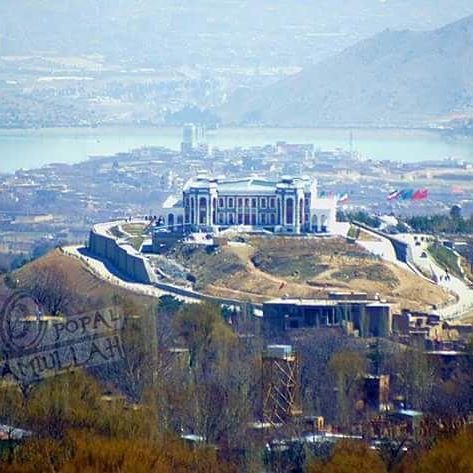

Afghan by descent, but brought up in England, she claims to have thought herself half Western liberal, half wild Afghan warrior. To try and resolve this conflict she went to Afghanistan at the time of the Soviet invasion and was propelled into the world of the mujahidin. She was twenty-one years old, and beautiful: dangerous some would think, but she spoke Farsi, knew all their traditions; they treated her as one of them. Her courage is such that even reading about some of her exploits is frightening. This book will speak not only to the many people who admire the Afghan people and pity their ordeals, but to those like Saira Shah who owe allegiance to two cultures … more and more of them now in the world.Saira Shah shares her memories of discovering the country of her parents when she becomes a journalist and travel to Pakistan and Afghanistan to find her father's paradise. She grew up with the old stories he shared and his nostalgia of a life before politics and international warfare in these countries destroyed everything. Beautiful gardens, unforgettable vistas made room for human suffering on an unimaginable scale.

Few invaders cared for this desolate crossroads of Asia where, the Afghans say, when God finished making the world, he laughed and threw down his rubbishShe kept going back to find the other half of herself.

Two people live inside me. Like a couple who rarely speak, they are not compatible. My Western side is a sensitive, liberal, middle-class pacifist. My Afghan side I can only describe as a rapacious robber baron. It revels in bloodshed, glories in risk and will not be afraidDespite the suffering and hardships, her paternal country grew on her. Captured her soul.

I began my quest for truth peddling lies in the offices of Fleet Street editors. I spoke fluent Persian; I was personally known to most of the mujahidin leaders; I was an experienced reporter, hardened to combat. Even as I uttered these outrageous falsehoods, I marvelled that anyone could believe them. I didn’t realize it then but, unconsciously, I was following in the footsteps of the very myths I was trying to put behind me.This is a deeply heartfelt story. I was at times so traumatized that I just couldn't continue reading. Yet, the well-written prose of this documentary memoir kept me coming back. Saira Shah shares her experience behind the documentary film she made and the challenges they had to endure to introduce the outside world to a region of the world where many people still haven't seen airplanes and where some groups live so remote, that they were, by the grace of God, not affected by the war.

‘This is a remarkable and essential book about Afghanistan which succeeds in describing the people of that country — men and also women — their identities, hopes, fears, generosity and cruelties, all of which have too long been buried under the rubble of endless geopolitical clashes. It is alive with detail, emotion, myth, fable, bleeding reality and those laughs and freedoms which arise defiantly out of the darkest of times to assert the human spirit. Saira Shah’s descriptions of her relatives - Auntie Soraya with her folded painted face, for example — are written from the position of an intimate who is also an outsider with values which do not forgive the unforgivable. The murders, threats, violence of life in the Afghanistan she has previously only known in the stories fail to really disarm this brave woman with enviable verve and imagination.’In the end I cried for the little children.

It struck me that a sense of humour may be the opposite of fanaticism, or at least its antidote. It is difficult to dream of martyrdom if you can see the funny side of life. Of course, the great Afghan poet Jalaluddin Rumi got there centuries before me, and said it better: "If you have no sense of humour, then you have an incompleteness in your soul."