What do you think?

Rate this book

212 pages, Paperback

First published September 1, 2010

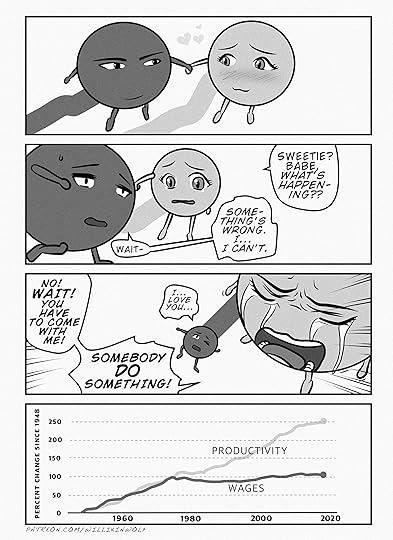

Once limited to asset markets, and to a very specific property of them, the scheme of liquidity irresistibly overflows and spread throughout the whole of capitalist society, evidently primarily serving those in a position to assert their desire as master-desire. Even though no market, especially not that of labour, can attain the degree of flexibility-reversibility of financial markets, liquidity draws the bullseye and pushes the master-desires towards obtaining the structural transformations that would allow them to get as close as they can. The most typical example is that of the capitalist argument that the only way to lower unemployment is to completely liberate layoffs from any regulatory framework.

For however successful it is, the process of epithumogenesis has the effect, and in fact the intention, of fixing the enlistee’s desire to a certain number of objects to the exclusion of others. Within capitalist organisations, the very function of hierarchical subordination is to assign each individual a defined set task according to the division of labour, namely, to an activity object that each must convert into an object of desire. [...] Subjection, even when it is happy, consists fundamentally in locking employees in a restricted domain of enjoyment.

But this [new] definition of class does not possess the simplicity of the initial bipolar scheme, since belonging to the ‘employee-class’ (the class of ‘labour’) is no longer itself as strongly predetermining as it used to be; crucially, it no longer has the homogeneity that enabled it (at times) to act as a historical driving force. Nevertheless, this relative fragmentation of the class structure and the ensuing blurring of the social landscape in no way prevents re-homogenisations from taking place, but these must follow a different logic, notably, the affective logic of discontent.