What do you think?

Rate this book

592 pages, Hardcover

First published May 26, 2011

An act is wrong just when such acts are disallowed by some principle that is optimific, uniquely universally willable, and not reasonably rejectable.[1]

…two people, White and Grey, are trapped in slowly collapsing wreckage. I am a rescuer, who could prevent this wreckage from either killing White or destroying Grey’s leg.[8]

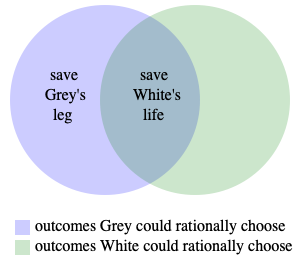

Grey could rationally choose that I save her leg, since this choice would be much better for her. But she would not be rationally required to make this choice. Grey could rationally choose instead that I save White’s life. Grey could rationally regard White’s well-being as mattering about as much as hers, and White’s loss in dying would be much greater than Grey’s loss in losing her leg.

White, in contrast, could not rationally choose that I save Grey’s leg. We could often rationally choose to benefit some stranger, I believe, even if our choice would make us lose a somewhat greater benefit. But there is too great a difference between the possible benefits to White and Grey. White would not have sufficient reasons to give up her life so that I could save Grey’s leg.[11]

Of our reasons for doubting that there are moral truths, one of the strongest is provided by some kinds of moral disagreement. Most moral disagreements do not count strongly against the belief that there are moral truths, since these disagreements depend on different people’s having conflicting empirical or religious beliefs, or on their having conflicting interests, or on their using different concepts, or these disagreements are about borderline cases, or they depend on the false assumption that all questions must have answers, or precise answers. But some disagreements are not of these kinds. These disagreements are deepest when we are considering, not the wrongness of particular acts, but the nature of morality and moral reasoning, and what is implied by different views about these questions. If we and others hold conflicting views, and we have no reason to believe that we are the people who are more likely to be right, that should at least make us doubt our view. It may also give us reasons to doubt that any of us could be right.[13]

…Parfit came to believe that dissent about ethics—especially dissent between leading philosophers—was evidence for its relativism. And he thought that relativism essentially collapsed into nihilism. If your moral truth conflicted with, but was no less valid than, my moral truth, this would show that, ultimately, nothing mattered.[14]

…the general tenor of the reviews was that Parfit’s project resembled a vast baroque cathedral that evoked a sense of awe less for its beauty than for its sheer construction. ‘It stands as a grand and dedicated attempt to elaborate a fundamentally misguided perspective,’ declared The New Republic. Several of the reviews mentioned the daunting length of the volumes; one reviewer went to the trouble of putting Volumes 1 and 2 on the scales: they weighed in at ‘4.8 pounds’ (2.18 kilos).[15]

It is often assumed that the word ‘wrong’ has only one moral sense. This assumption is most plausible when we are considering the acts of people who know all of the morally relevant facts. We can start by supposing that, when we think about such acts, we all use ‘wrong’ in the same sense, which we can call the ordinary sense. In many cases, however, we don’t know all of the relevant facts, and we must act in ignorance, or with false beliefs. When we think about such cases, we can use ‘wrong’ in several partly different senses. Some of these senses we can define by using the ordinary sense. Some act of ours would be

wrong in the fact-relative sense just when this act would be wrong in the ordinary sense if we knew all of the morally relevant facts,

wrong in the belief-relative sense just when this act would be wrong in the ordinary sense if our beliefs about these facts were true,

and

wrong in the evidence-relative sense just when this act would be wrong in the ordinary sense if we believed what the available evidence gives us decisive reasons to believe, and these beliefs were true.[16]

… [a few pages later]

wrong in the moral-belief-relative sense just when the agent believes this act to be wrong in the ordinary sense.[17]