What do you think?

Rate this book

209 pages, Hardcover

First published January 1, 1998

And so it is a reader, first and foremost, that I wish to pay tribute to these colleagues who have gone before me, in the form of these extended marginal notes and glosses, which do not otherwise have any particular claim to make.

I have learned how it is essential to gaze far beneath the surface, that art is nothing without patient handiwork, and that there are many difficulties to be reckoned with in the recollection of things.

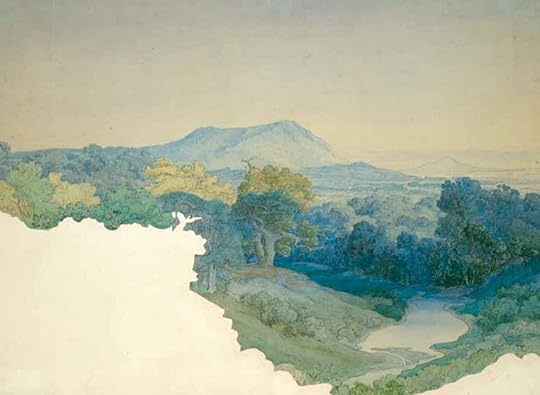

At the end of September 1965, having moved to the French-speaking part of Switzerland to continue my studies, a few days before the beginning of the semester I took a trip to the nearby Seeland, where, starting from Ins, I climbed up the so-called Schattenrain. It was a hazy sort of day, and I remember how, on reaching the edge of the small wood covering the slope, I paused to look back down at the path I had come by, at the plain stretching away to the north criss-crossed by the straight lines of canals, with the hills shrouded in mist beyond; and how, when I emerged once more into the fields above the village of Lüscherz, I saw spread out below me the Lac de Bienne, and sat there for an hour or more lost in thought at the sight, resolving that at the earliest opportunity I would cross over to the island in the lake which, on that autumn day, was flooded with a trembling pale light. As so often happens in life, however, it took another thirty-one years before this plan could be realized and I was finally able, in the early summer of 1996, in the company of an exceedingly obliging host who lived high above the steep shores of the lake and who habitually wore a kind of captain's cap, smoked Indian bidis and seldom spoke, to make the journey across the lake from the city of Bienne to the island of Saint-Pierre, formed during the last ice age by the retreating Rhône glacier into the shape of a whale's back—or so it is generally said.

At any rate, in the few days I spent on the island—during which time I passed not a few hours sitting by the window in the Rosseau room—among the tourists who come over to the island on a day trip for a stroll or a bite to eat, only two strayed into this room with its sparse furnishings—a settee, a bed, a table and a chair—and even those two, evidently disappointed at how little there was to see, soon left again. Not one of them bent down to look at the glass display case to try to decipher Rosseau's handwriting, nor noticed the way that the bleached deal floorboards, almost two feet wide, are so worn down in the middle of the room as to form a shallow depression, nor that in places the knots in the wood protrude by almost an inch. No one ran a hand over the stone basin worn smooth by age in the antechamber, or noticed the smell of soot which still lingers in the fireplace, nor paused to look out the window with its view across the orchard and a meadow to the island's southern shore.

For me, though, as I sat in Rosseau's room, it was as if I had been transported back to an earlier age, an illusion I could indulge in all the more readily inasmuch as the island still retained that same quality of silence, undisturbed by even the most distant sound of a motor vehicle, as was still to be found everywhere in the world a century or two ago.

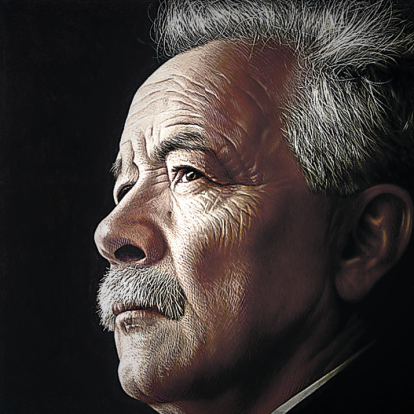

And so we see Mörike at the last sitting in the garden surrounded by his wife's relations on a hot summer's day, the only one with a book in his hand, and in the end not very content in his role as a poet, from which he—unlike his clerical calling—can no longer retire. Still he has to torment himself with his novel and other such literary matters. But for years now the work has not really been going anywhere. The painter Friedrich Pecht, in a reminiscence about this time, relates how on several occasions he observed Mörike noting things down which came into his head on speecial scraps and pieces of paper, only soon afterwards to take these notes and 'tear them up into little pieces and bury them in the pockets of his dressing-gown.'