What do you think?

Rate this book

140 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1979

"[Fitzgerald] may have been born in grandeur, but her husband was an alcoholic who drank up every penny, was convicted for stealing checks, and lost his job. Eventually she lived with him and their three children on a houseboat on the Thames in a chic part of London; the boat sank twice, and her family was homeless for a while, then given public housing."I just had no idea this novel was so autobiographical. That adds a bit of richness to it, doesn't it? Cool. 4/18/18

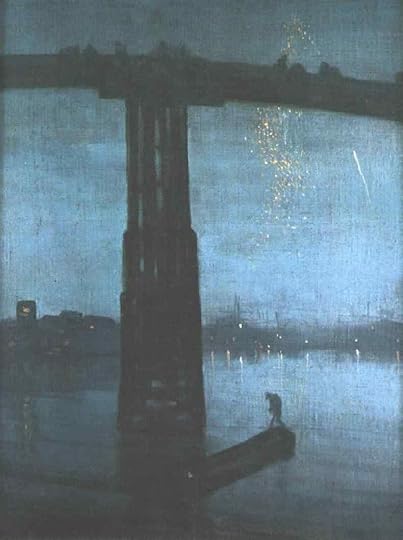

The barge dwellers, creatures of neither firm land nor water, would have liked to be more respectable than they were …… They aspired to the Chelsea shore … But a certain failure, distressing to themselves, to be like other people, caused them to sink back, with so much else that drifted or was washed up, into the mud moorings of the great tideway.

Its right for us to live where we do, between land and water. You [Neena] my dear you’re half in love with your husband, then there’s Martha who’s half a child and half a girl. Richard who can’t give up being half in the Navy ,Willis who’s half an artist and half a longshoreman, a cat who’s half alive and half dead.

The attendant watched her, hoping that she would get a little closer to the picture, so he could relieve the boredom of his long day by telling her to stand back

… one of many enterprises in Chelsea which survived entirely by selling antiques to each other.