What do you think?

Rate this book

211 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1884

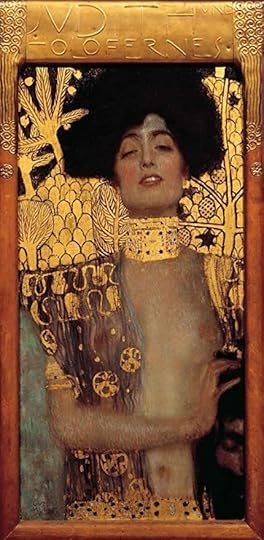

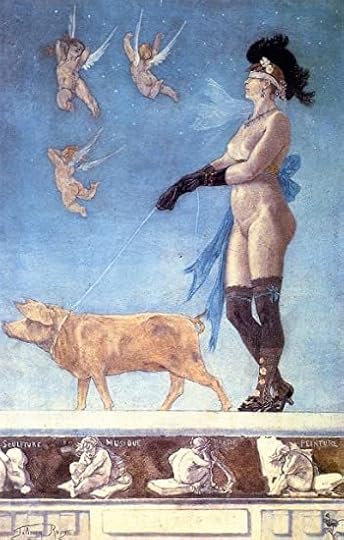

Rachilde appropriated Baudelaire's legacy of representing women as split into two sharply contrasting types: on the one hand, idealized woman-beauty as artifice and artifact; on the other hand, organic, embodied woman, monstrously insatiable in her sensual appetites, a degenerate and disease-bearing body. But she rewrote and regendered the male decadent gaze that split woman into a costumed, made-up, bejewled, inorganic, and inanimate representation of beauty (woman as work of art) and the unadorned person of corporeal appetites. Huysmans also adopts this construction but merely elaborates and develops its duality using the perspective of his male protagonist Des Esseintes in A rebours (Against the Grain). This novel—published, like Monsieur Vénus, in 1884—is widely accepted as the quintessential decadent novel. The divergent fates of the two novels—A rebours's fame as a classic of decadence and Monsieur Vénus's relative obscurity—tells an important tale.Being a queer person who's too old for the teen trends of the 21st century and too young to have either died of AIDS or sold out during the heyday of radical feminism means navigating a landscape of virulently bad faith and concerted ignorance on one side and predatory dehumanization and cult-like indoctrination on the other. Throw in my willingness to get down and dirty with the actual history and relevant literature written during the decades just after 'heterosexuality' was first established as anything worth paying attention (which, by the way, if you're thinking that this occurred at any point before the 19th c. for a particularly Anglo heavy portion of the world, you've got a lot of learning to do), and it's borderline nauseating watching people read translations of ancient Greek texts and go, diversity win! This socially sanctioned sexual predator of underage boys is gay! This is why I'm kind of glad that, despite the trend of 'malewife' that pops up on my periphery every once in a while, the chance of any of those 'hip' types who are the loudest about that kind of content coming across this work and actually giving it the kind of go that they're capable of is borderline nonexistent. True, Vallette-Eymery's tale is a dizzying exploration of sociocultural gender/sexuality norms by the kind of author (hint: not a dude) writing during the kind of time (hint: not post-WWII) that the typical Wikipedia article and its dudebro editor would simply declare to never have existed, but it takes the horrendously transphobic stereotypes specifically regarding trans men and the 'gay panic defense' law of today and pushes both to extremes that, judging by what the author churned out in her later days, were in part done for the edgy lulz. I've no doubt about the overall value of the text, and there's a great deal of amazing analysis that can be drawn from it and potentially expanded upon in the work of enterprising queer authors of today. However, do I trust the white cis gays with their 'q-slurs' and their 'cops need to be at Pride to keep the kinky degenerate freaks out' to do the necessary work? Fuck no.

But suddenly Jacques's arrival, carelessly disturbing them in their disdainful reflections, reduced them to silence. They were about to move off en masse to show their contempt for this obscure dauber of forget-me-nots when they all felt at the same time a bizarre commotion that riveted them to the spot. Jacques, his head thrown back, still had his smile of a young girl in love; his open lips showed off his pearly teeth; his eyes, enhanced by bluish circles, maintained a glistening radiance; and under his thick air, his delicate ears, opening like some purple flower, made all of them shiver inexplicably at once. Jacques passed them without noticing them; his hips, well defined under his evening clothes, brushed them lightly for a second...and with one movement they clenched their hands, suddenly grown moist.

When he had moved far off, the marquis let fall this banal phrase:

"It's very hot in here, gentlemen; 'pon my honor, it's unbearable!..."

They all repeated in chorus:

"It's unbearable!...'Pon our honor, it's too hot!..."