What do you think?

Rate this book

416 pages, Hardcover

First published September 27, 2011

The kid reminds the Professor of Huckleberry Finn somehow. Here he is now, long after he lit out for the Territory, grown older and as deep into the Territory as you can go, camped out alone where the continent and all the rivers meet the sea and there’s no farther place he can run to. The Professor wants to know what happened to that ignorant, abused, honest American boy between the end of the book and now. After he ran from Aunt Sally and her “civilisin,” how did he come years later to having “no money, no job, no legal squat”?But the Professor has issues of his own. He is a huge man of maybe five hundred pounds, and spends long hours feeding his own addiction, eating. While society may regard his addiction with increasing disdain, no one suggests that fat people be shunned into leper colonies at the edges of town. The Professor has some rather darker secrets as well, which play into the final stages of the book. I will not reveal that info here, but the fact that he has a secret past helps link the Professor thematically with those he is researching.

When a society commodifies its children by making them into a consumer group, dehumanizing them by converting them into a crucial, locked–in segment of the economy, and then proceeds to eroticize its products in order to sell them, the children gradually come to be perceived by the rest of the community and by the children themselves as sexual objects. And on the ladder of power, where power is construed sexually instead of economically, the children end up at the bottom rung.I do not want to give the impression that this is a bloodless lecture on a social issue. Banks is a great novelist and he has given us relatable characters. The Professor struggles with his secrets and addictions. The Kid recognizes that he has done something wrong, but finds some light, instead of succumbing to the sort of dark depression that anyone in such a situation might experience. There are some fog-thin background characters, and some who step a bit out of that mist into further clarity, but the humanity of the Kid and the Professor are primary. There are even non-human characters who work incredibly well as emotional foils. Iggy is the Kid’s rather large pet iguana and bff. Later Einstein, a parrot with a few pretty good lines and Annie an elderly dog add to the warmth factor.

The eye of the hurricane: it’s a metaphor for the mental and emotional space where he’s lived most of his life. He thinks this and smiles inwardly. Never quite thought of it that way. Nice, the way the world that surrounds one, the very weather of one’s existence, provides a language for addressing the world inside.Our secrets and lies make for us a skin to protect our inner selves from the world. What happens when that skin is perforated, or removed? Are we freed or endangered? And what is the truth anyway? The book takes a bit of an existential turn. A new character, the Writer, is introduced late in the game to insert the author into the story. A conversation between the Kid and the Writer embodies this.

If everything’s a lie and nothing’s true like you said, then it doesn’t matter if the Professor’s story is bullshit, right? Is that what you’re saying?Early on, the Professor uses a treasure map to inspire the Kid, and the inspiration is drawn from belief, not from the reliability of the map. While I take Banks’ point that belief can go a long way toward inspiring one to success, that opens access to a very slippery slope. Not all beliefs are equal, and many are downright dangerous. Putting the contrast between a faith-based worldview and a scientific one in such black and white terms, with the corresponding judgment, is insulting and dangerous. It offers sustenance to those who would seek to inflict their personal beliefs on people who do not share them. There is plenty of room for both science and feeling in this world.

What you believe matters, however. It’s all anyone has to act on. And since what you do is who you are, your actions define you. If you don’t believe anything is true simply because you can’t logically prove what’s true, you won’t do anything. You’ll end up spending your life in a rocking chair looking out at the horizon waiting for an answer that never comes. You might as well be dead. It’s an old philosophical problem.

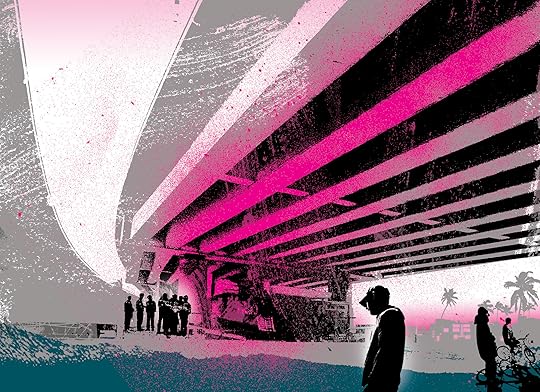

This is bleak stuff, with flashes of humor that land like sparks on dry grass, and also pretty fascinating. A two-time Pulitzer Prize finalist, Banks may be the most compassionate fiction writer working today, and the Kid is only his most recent lens into the souls of seemingly decent men who do terribly indecent things out of ignorance, thirst and desperation in a deeply uncaring world. Balancing impressively on a moral tightrope, Banks never absolves the Kid of his actions even as he sympathizes with him. Source: http://www.nytimes.com/2011/10/09/boo...

He was no more or less than what he seemed to be – a fatherless white kid who graduated high school without ever passing a single test or turning in a single paper, a kid who could barely read and write or do math beyond the simplest arithmetic, who was hooked for years and maybe still was hooked on porn and jacking off and never had a girlfriend or a best friend and belonged to no one's posse – but that was okay to the Kid back then.

A huge hairy figure sweating inside the ten yards of brown cloth it takes to cover him with a suit, a man submerged in a body as large as a manatee's, graceless, slow moving, arms and thighs rubbing themselves raw, spine and knee and ankle joints nearly to the breaking point by the weight they must support, enlarged heart thumping rapidly from the effort of shoving blood and oxygen through all that flesh, overheated lungs gasping from the work of getting that enormous bulk up the incline to the parking lot, liver, kidneys, glands, digestive tract, all his organs overworked for half a century to the point of exhaustion and collapse – a man with two bodies, one dancing inside his brain, a hologram made of electrons and neurons going off like a field of fireflies on a midsummer night, the other a moist quarter-ton packet of solid flesh wrapped in pale human skin.

Perhaps that's the one constant that is shared by all those separate compartments he lives in – a profound sense of isolation, of difference and a solitude that is so pervasive and deep that he has never felt lonely. It's the solitude of a narcissist who fills the universe entirely, until there is no room left in it for anyone else. In every life he has led, every identity he has claimed for himself and revealed to others, his profound sense of isolation was then and is now his core.

(T)he second he saw himself on the screen he felt like all his atoms were instantly reconfigured. It was as if he had never seen himself in a mirror before. It was like being touched by an angel. He had an actual body and it was not just his body, something he merely possessed, it was him!

What you believe matters, however. It’s all anyone has to act on. And since what you do is who you are, your actions define you. If you don’t believe anything is true simply because you can’t logically prove what’s true, you won’t do anything. You won’t be anything. You’ll end up spending your life in a rocking chair looking out at the horizon waiting for an answer that never comes. You might as well be dead. It’s an old philosophical problem.