What do you think?

Rate this book

336 pages, Hardcover

First published January 1, 2006

As we flew over the target it looked to me very much as any normal normal village would look: on the edge of a river, sampans and fish nets in the water. It was a peaceful scene. Major Carson put our plane into a steep dive. I could see the napalm bombs dropping from the wings. The big bombs first . . . The first pass had a one-two effect. The napalm was expected to force the people--fearing the heat and burning--out into the open. Then the second place was to move in with heavy fragmentation bombs to hit whatever--or whomever--had rushed out into the open. . .Fall stepped on a land mine during an ill-advised fifth visit to Vietnam in 1967. He was married by this time, with three young daughters, the youngest an infant. He had lost one kidney to an infection and the other one was severely damaged, requiring thrice-daily doses of medication.

We came down low, flying very fast, and I could see some of the villagers trying to head away from the burning shore in their sampans. The village was burning fiercely. I will never forget the sight of the fishing nets in flame, covered with burning, jellied gasoline. Behind me I could hear--even through my padded helmet--the roar of the plane's 20-millimeter cannon as we flew away.

There were probably between 1,000 and 1,500 people living in the fishing village we attacked. It is difficult to estimate how many were killed. It is equally difficult to judge if there actually were any Viet Cong in the village and if so, if any were killed.

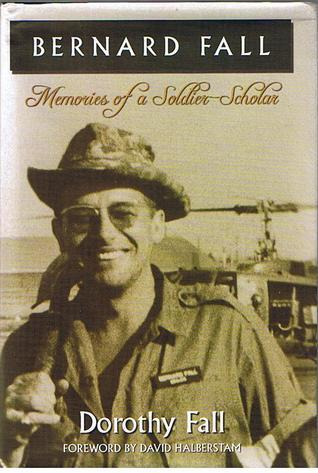

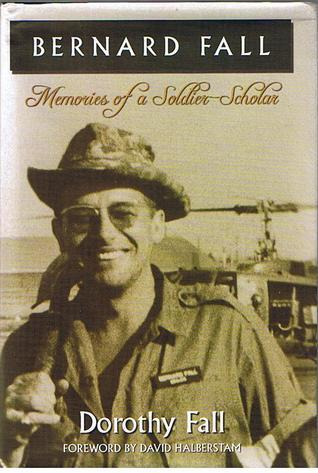

Darling,This book is his widow's attempt, some forty years after the fact, to honor his life and make sense of his pointless death. As a chronicle, it reads well, interweaving history with Bernard's life and work. I admire the man for the strength of his will and the clarity of his perception. He was driven not by self-righteousness, but by the passion to get things right, to find the truth.

You will see this only if anything has happened. I want you to know that I loved you and the children terribly much and was proud of you.

If I assumed the risks I did in this incredibly stupid and brutal war, I did so because somebody had to be a witness to what was happening. I hope that those poor blind men who direct America's policies will awaken to the real facts before it is too late. In that case, whatever happened to me will not have happened in vain. I know that you will be thinking of me as I will think of you--no matter where I will be.

Love,

Bernard

Is this crazy or what? He has to do this to feel great? What was I thinking? Was I joining him in saving the world? Was his mission to warn the country more important than his children and me? Was I so without backbone that he and I were ready to sacrifice ourselves for this insane war that he knew we could never win? Or was it his search for the camaraderie, for the last hurrah? He must be thinking that if he were to die soon anyway, why not in the thrill of battle?Christian Parenti reviewed Dorothy Fall's memoir for The Nation in 2007, as the Iraq surge was getting underway. Fall's ghost, he commented ruefully, haunts us today:

The cult of war-oriented experiential knowledge is back. Fall’s epistemology placed great importance on seeing one’s subject up close. “You cannot keep up your convictions if you don’t base them on things that you have witnessed for yourself,” Fall said, explaining why he kept returning to Vietnam.Parenti raises doubts about the motivations of embedded journalists--the "flâneurs in hell," as he nicely terms them--who cover wars in the Bernard Fall tradition, doubts that go well beyond Dorothy's guilty musing.

. . .it is not simply knowledge that is gained in a war zone but experience, and it can be quite nasty. The typically male lust to watch war is not always so noble as the “truth-telling witness” metaphor would suggest. Nor is the flâneur in hell simply in it for the adrenaline. The ugly fact is that for many Western reporters watching war often involves a somewhat sadistic thrill.I appreciate Parenti's concern, given the context in which he was writing about Fall's exploits. His review is one of the most thought-provoking pieces I've read on the lessons of Vietnam for the current day, but Dorothy Fall's memoir deserves to be read for its own sake, for the insights it provides into a troubled man's quest for a heroic death.

Even as one sympathizes with the civilians who are killed and maimed and trapped in the war zone, one also tends to identify with the killers, rapists and arsonists–they are very frequently one’s hosts, or at least one’s most sought-after sources and protectors.