Underdogs often command some degree of sympathy, simply because they are fighting against superior odds. And at least some of the Mexican revolutionaries who fight their way through Mariano Azuela’s 1915 novel The Underdogs will no doubt enlist reader sympathies – even as the thoughtful reader may question some of the motivations of some of those revolutionaries.

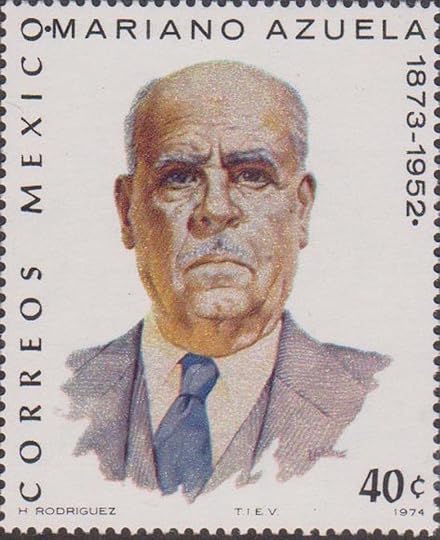

When Azuela wrote The Underdogs – its title in the original Spanish was Los de abajo, or Those from Below – he was writing from experience. A physician by training, he served as a combat medic in the Mexican Revolution of 1910. And the picture that he draws of that war is a grim one – a tableau that combines high ideals with muddled execution, a great deal of uncertainty, and a good deal of bloody violence.

Readers outside of Mexico may not be familiar with the events set forth in The Underdogs -- a novel that, in its English printing, has the subtitle A Novel of the Mexican Revolution. Therefore, in hopes of helping any non-Mexican readers who are not already familiar with the events of la Revolución Mexicana, I offer a brief setting-forth of the revolution’s various phases or fases:

Fase Uno (Phase 1), 1910-11: Francisco Madero, a leader committed to democracy, overthrows General Porfirio Díaz, an autocrat who had ruled Mexico for 30 years.

Fase Dos (Phase 2), 1913: General Victoriano Huerta, an autocrat like Díaz, takes over the government. The pro-democracy Madero and his vice president are murdered, almost certainly on Huerta’s orders.

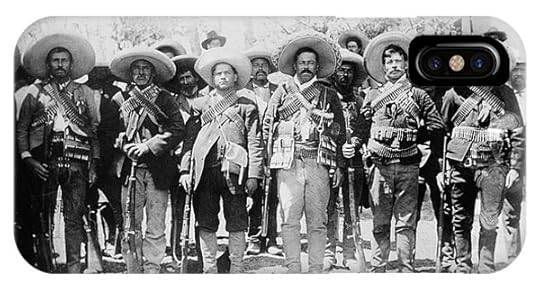

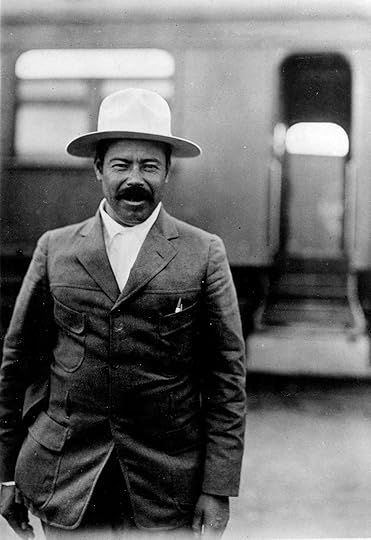

Fase Tres (Phase 3), 1913-15: Huerta’s dictatorial rule is opposed by four leaders – Venustiano Carranza, Álvaro Obregón, Pancho Villa, and Emiliano Zapata. By 1915, this alliance has defeated Huerta and forced him to flee Mexico.

Fase Cuatro (Phase 4), 1915-20: The alliance breaks up, with Carranza and Obregón pitted against Villa and Zapata.

Confused yet? Considering the chaotic turns of events that characterized this revolution, it should be no surprise that the revolutionaries who are the main characters of Los de abajo sometimes seem unsure who or what they are revolting against, or why. Indeed, author Azuela himself went from following Carranza to following Villa, and some of his perspectives regarding the revolutionary way of life seem starkly cynical.

The protagonist of The Underdogs, and the leader of the revolutionary band whom the reader follows, is one Demetrio Macías. An effective leader and man of action, Demetrio is also someone who originally joined the revolution for reasons having as much to do with the personal as with the political.

In contrast with Demetrio’s down-to-earth, realistic approach to revolution – trying to make sure that his men have food to eat, ammunition to fight with, that sort of thing – one also sees the idealistic side of revolution, in the form of Luis Cervantes, a high-minded young man who wants to join a fight that he’s written a great deal about but not seen much of.

When he first meets the revolutionaries that he has been seeking out, Luis declares grandiloquently that “The revolution benefits the poor, the ignorant, all those who have been slaves all their lives, all the unhappy people who do not even suspect they are poor because the rich who stand above them, the rich who rule them, change their blood and sweat and tears into gold…” But he spends the first part of his time with the revolutionary forces suffering from a bullet wound and wondering whether he’ll be executed as a federal spy.

Luis’s naivete makes him a good surrogate for the reader, as Demetrio eventually takes the lad under his wing and starts teaching Luis the basics of fighting in this revolution – like attending to the tactical details most likely to ensure battlefield success. Preparing for an assault on a group of federales, Demetrio dismisses out of hand Luis’s suggestion of reconnoitering the federal position or seeking out a guide:

“No, curro….We hit ’em when they least expect it, and tha’s that. Tha’s how we’ve always done it, many times before, and it’s how we’ll always do it. Ever seen how squirrels stick their heads outta their holes if ya fill ’em up with water? Well, these damned little conservative mongrels will come out just as stunned when they hear the first shots. They’ll come out, and we’ll be there ready to use their heads as target practice.”

The theme of disillusionment quickly becomes pre-eminent in Los de abajo. When Demetrio’s forces join with those of General Pánfilo Natera, in preparation for an (ultimately unsuccessful) attack on the town of Zacatecas, Luis Cervantes encounters an acquaintance named Solis, an officer in Natera’s army. Observing with mild irony Luis’s revolutionary zeal, Solis sets forth with some asperity his own experience of the revolution:

I hoped to find a meadow at the end of the road. I found a swamp. Facts are bitter; so are men. That bitterness eats your heart out; it is poison, dry rot. Enthusiasm, hope, ideals, happiness – vain dreams, vain dreams….When that’s over, you have a choice. Either you turn bandit, like the rest, or the timeservers will swamp you…”

Anticipating the shocked Luis’s next question, Solis adds, “You ask me why I am still a rebel? Well, the revolution is like a hurricane: if you’re not in it, you’re not a man…you’re a leaf, a dead leaf, blown by the wind.”

But it takes Luis time to learn the realities of the revolution – and some truths about himself as well. Luis meets a wild set of supporting characters – prominent among them a tough-minded camp follower nicknamed “War Paint,” who regularly bestows her vividly expressed contempt upon everyone around her – and is dismayed at how the rebels behave. Seeing all the looting that goes on when the rebels have taken a town from which federales and their sympathizers have fled, Luis denounces the brigandage that he sees around him, complaining that “this sort of thing hurts our prestige, and worse, our cause!” In reply, Demetrio dryly points out that Luis himself has stolen a box of diamond earrings.

The revolutionary band’s wanderings and encounters, with plenty of drinking and quarrelling and some sexual activity, come to seem increasingly pointless – more like a rock band’s on-tour misadventures than a military campaign. And the revolution starts to become an end in itself.

Part Three of The Underdogs is set in May of 1915, by which time the revolution has settled into its singularly unfocused fourth phase. And this particularly grim part of the book centers around this quote from a poetry-minded revolutionary named Valderrama: “Villa? Obregón? Carranza? What’s the difference? I love the revolution like a volcano in eruption; I love the volcano because it’s a volcano – the revolution, because it’s the revolution! What do I care about the stones left above or below after the cataclysm? What are they to me?” In other words, the point of the revolution is to keep on fighting the revolution.

One of the revolutionaries, Anastasio Montanez, asks an eminently sensible question: “What I can’t get into my head…is why we keep on fighting. Didn’t we finish off this man Huerta and his Federation?” His fellow soldiers only laugh at him in response, and the novel’s narrator thus sums up the state of mind behind the soldiers’ laughter: “If a man has a rifle in his hands and a beltful of cartridges, surely he should use them. That means fighting. Against whom? For whom? That is scarcely a matter of importance.”

Even the renowned Pancho Villa – the charismatic leader for whom they are fighting – comes to be seen through the same lens of disillusionment. When news comes that Villa has been defeated at Celaya by Obregon’s forces, the dispirited revolutionaries fall into “a lugubrious silence”, and the narrator sums up their state of mind by observing that “Villa defeated was a fallen god; when gods cease to be omnipotent, they are nothing.”

The book’s cynical outlook regarding the revolution is reinforced one last time, by an affecting scene when Demetrio briefly gets to see his beautiful young wife and their son, after a separation of two years. Demetrio makes clear to his wife that he intends to return to the revolution, even though his wife asks him to stay with her and expresses her certainty that this campaign will be his last:

”Why do you keep on fighting, Demetrio?”

Demetrio frowned deeply. Picking up a stone absent-mindedly, he threw it to the bottom of the canyon. Then he stared pensively into the abyss, watching the arch of its flight.

“Look at that stone; how it keeps on going….”

Once again, a fighter cannot explain why the fight must continue; the revolution has become a perpetual-motion machine of blood and violence. It is against the backdrop of this tragic final conversation that The Underdogs moves toward its grim resolution.

Novelist Azuela left the Mexican Revolution in 1915 and took refuge on the U.S. side of the border, at El Paso, Texas, where he wrote The Underdogs. The book succeeds because of the immediacy of detail with which Azuela sets forth the day-to-day life of the revolutionaries – and succeeds even more through its moving depiction of how soldiers who begin by fighting for high ideals can end up fighting for nothing more than the “right” to keep on fighting.