What do you think?

Rate this book

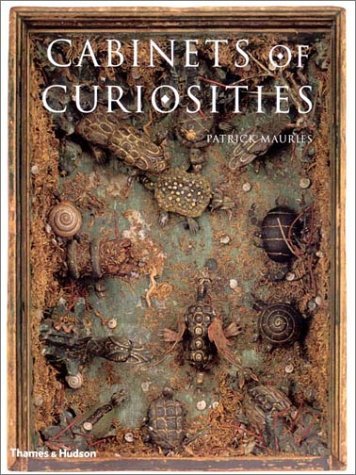

256 pages, Hardcover

First published November 1, 2002

Bezoar was a stone which when hollowed out into a cup was believed to render poisons harmless.This sentence is true enough, but a little misleading as it stands. A bezoar isn't an inorganic stone—it's a gastrointestinal accretion of indigestible material, usually biological in origin (more like a kidney stone than a rock from the ground), and although some bezoars did get big enough to be made into cups, they were more commonly placed into cups as a specific against poisoning. (And, interestingly, it turns out that at least some bezoars can absorb arsenic... But I digress.)

—p.173

There was no place for the inexplicable or the bizarre in a culture that demanded, then as now, a reality that was on the way to being explained, a reality with no parts left over or superfluities; henceforth, a predictable nature would obey the laws of probability, leaving no room for exceptions, just as the 'mediocrity' demanded by society left no room for gratuitous excess ("the metaphysical shift from marvellous to uniform nature paralleled a shift in cultural values from princely magnificence to bourgeois domesticity").

—pp.193-194

'A slight slippage'Whew! But... the above just serves as an introduction to that second great shock of recognition, the one I mentioned at the beginning of this review; the very next paragraph of Cabinets of Curiosities showcases a specific touchstone for the bizarre that I've mentioned in several previous reviews, a place I've actually visited: the marvelous modern cabinet of wonders, housed in an unassuming building in Culver City, California, known as the Museum of Jurassic Technology!

One of the consequences of the disappearance of the concept of the work, in the classical sense of the term, from modern and contemporary art has been the acceptance and recognition of realms and endeavours that have hitherto been excluded from the main body of art, or consigned to the fringes of the pathological. 'Natural poetry', dandies dabbling in extravagance and excess, Art Brut or Outsider Art: we are surrounded now by works without artists, or in which the vestiges of a consciousness or an identity have vanished, and artists without works, whose only legacy is their lives, or even some device, place or mere intention. As an accumulation of objects, a theatre of intimacy, a fundamentally eclectic assortment of objects, the cabinet of curiosities belongs as we have seen, under numerous different guises and via a number of essential connections, to the history of modern and contemporary art. But the closing years of the twentieth century witnessed the emergence of a final renaissance, as spectacular as it was unexpected, of the Wunderkammern, in a resurgence that took place, moreover, outside the confines of any cultural establishment, no matter how cutting-edge or controversial. Quite the reverse: a côterie of collectors and cognoscenti now chose, quietly and in private, to adopt the vanished cabinets of curiosities as the décor against which they lived their daily lives, creating spaces saturated with references and allusions, réveries around themes and objects long ago consigned to oblivion, the carefully meditated frameworks of a personal scenography which to the astute observer will appear as so many works without titles, paradoxical testimonies of daily life in the era of new technology.

—p.244

In other words, the space presents all the distinguishing marks of a museum, albeit a slightly impoverished one, hard up and improvised, put together in ad hoc fashion by a collector tinged with fanatacism and not wholly equipped to realize his ambitions. One becomes dimly aware, as a perceptive visitor has observed, 'that something is wrong. There is a very slight slippage which is the very essence of the place.'

—p.245

We should not be tempted to over-simplify the multiplicity of the reasons that lay behind the progressive dissociation of the motives that bound together the culture of curiosities, and the marginalization that then ensued.