What do you think?

Rate this book

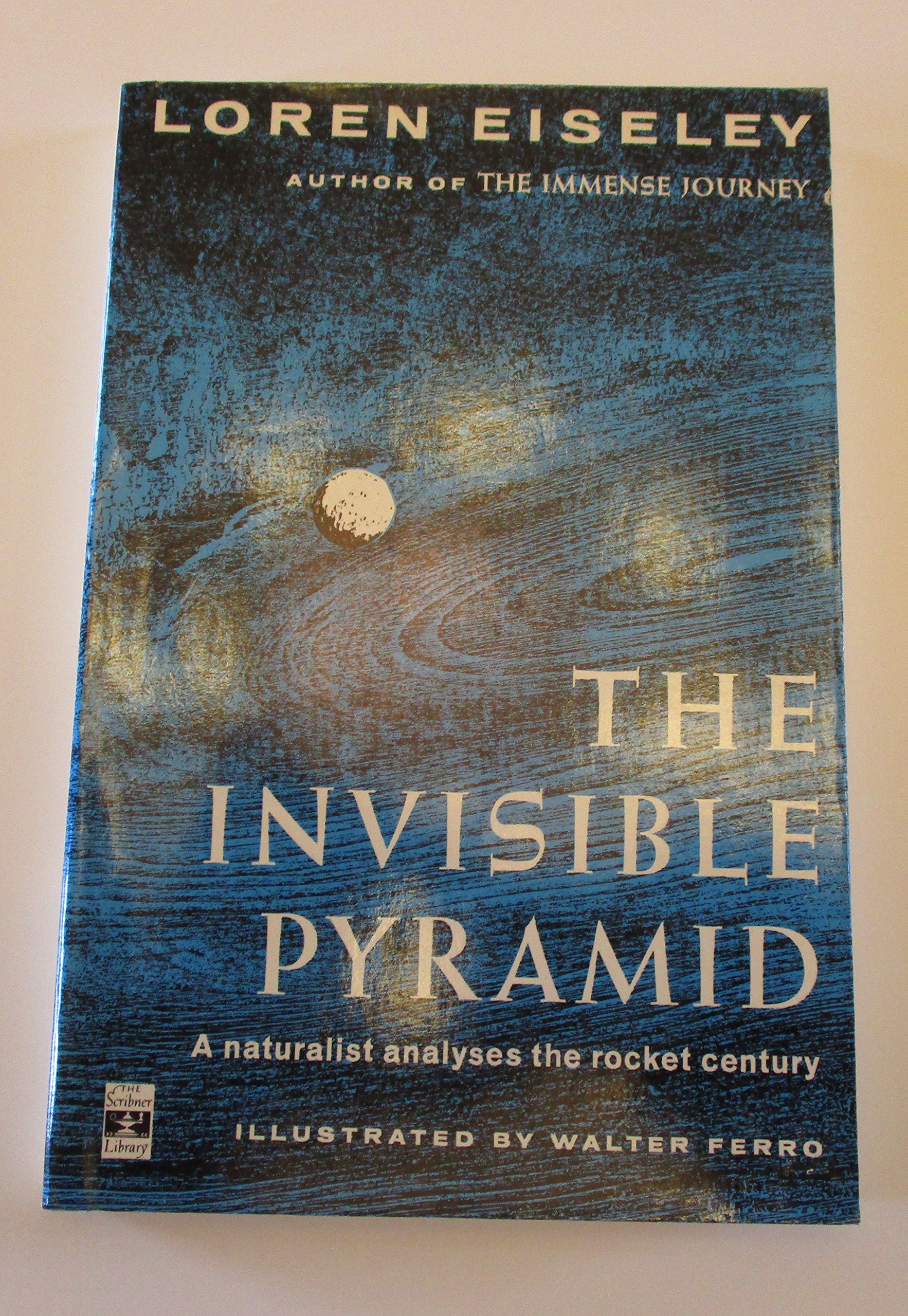

Unknown Binding

First published January 1, 1970

For centuries we have dreamed of intelligent beings throughout this solar system. We have been wrong; the earth we have taken for granted and treated so casually—the sunflower-shaded forest of man’s infancy—is an incredibly precious planetary jewel. We are all of us—man, beast and growing plant—aboard a space ship of limited dimensions whose journey began so long ago that we have abandoned one set of gods and are now in the process of substituting another in the shape of science.He further writes of spores and earth eaters in describing recent human attitudes and behaviors; I agree. The future appears far from perpetual harmony. Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme! Let us awaken from our trance with some haste, comrades.

We have long passed the simple point at which science presented to us beneficent medicines and where, in the words of José Ortega de Gasset, science and civilization shaped by it could be regarded as the self-objectification of human reason. It is one thing successfully to plan a moon voyage; it is quite another to to solve the moral problems of a distraught, unenlightened, and confused humanity.But then, Eiseley did not foresee that science in our own time, some forty-five-odd years later, was in danger of being dragged off its pedestal by a society that proposed to replace it by an anti-intellectual pseudo-religious cult. But then, Eiseley also foresaw the possibility of that happening:

Some decades ago Henry Phillips of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology expressed this dilemma succinctly. "What will happen five minutes from now is pretty well determined," he wrote, "but as that period is gradually lengthened a larger and larger number of purely accidental occurrences are included. Ultimately a point is reached beyond which events are more than half determined by accidents which have not yet happened. Present planning loses significance when that point is reached.... Here is the fundamental dilemma of civilization.... there is serious doubt whether the way forward is known"Reading Eiseley is a humbling experience. Here there is no unimpeded march to the heights. He knows: He is holding the bones and other relics of failed civilizations in his hands.